Becoming Saints

"Arise and shine forth, that thy light may be a standard for the nations.”

“The only real sadness, the only real failure, the only great tragedy in life, is not to become a saint.” —Léon Bloy

Who was the first Christian saint? That depends on how one defines the term. If saint means remarkably devoted follower of Jesus, the first is probably his mother Mary, who accepted with faith Gabriel’s message. If saint means special proclaimer of the good news of Christ, then John the Baptist, or perhaps Simon Peter, who were the first to recognize Jesus as the messiah. If saint is defined the way Catholics use the word, as someone residing in heaven, then the first is technically Dismas, the penitent thief who Jesus promised on the cross would be with him that day in paradise. Or, by that logic, perhaps those raised to heaven even earlier, such as Moses, Elijah, or Enoch. On the other hand, if a saint is someone who dies testifying of Christ, then, as the first martyr, Stephen has the best claim, having been stoned to death by the Sanhedrin for his witness.

These are generally the kinds of people we have in mind when we think of the word saint—individuals exemplifying heroic faith, virtue, character, and sacrifice. People worthy of emulation and veneration.

But saint didn’t originally have this meaning. The English word is derived from the Latin sanctus, which represents the Greek hagios and the Hebrew qādōsh. These words, sanctus, hagios, qādōsh, were applied to God, but also to people and things consecrated and set apart for a sacred purpose or office—made “holy to God.” Jerusalem was the holy city not because its residents were especially righteous (usually quite the contrary), but because it had been chosen by God and set apart for a special purpose. Sanctus, when applied to a person, did not necessarily connote high moral quality.

In fact, initially, the word saint did not refer to individuals at all, but to a community. For instance, in his letters, Paul addresses himself to the saints in Achaia, at Ephesus, at Philippi, at Colossae. By saints he means all the members of the Christian communities in those places, God's holy people, the New Israel. It did not mean that all Christians had achieved a state of perfect moral rectitude, but that they also had been called to God’s service and were now together learning how to “turn away from evil and do good” (Ps. 34:14), to “strive for peace” (Heb. 12:14), and to live “as becometh saints (Eph. 5:3).”

In time, the term saint came to be applied to particular categories among the faithful: to those who had died “in the Lord,” to the martyrs, and to the first monks. At the same time, saint in the singular began to be used as a term of individual appreciation or as a sort of official title, especially for a bishop. Only later did saint became the title of honor and respect used individually for persons distinguished among their fellow Christians for the degree of their devotion to Christ.

Early Christians soon began to call on those who had received this honorific in prayer, entreating these holy inhabitants of heaven to intercede on their behalf. They revered and treasured the bodily remains of the saints and named their children and churches after them. And each year on the anniversary of the saint’s death, the faithful would gather at the grave, celebrate the Eucharist, and have a “feast day”—an occasion not of mourning but of rejoicing and triumph, and the root of our word festival.

The first such annual commemoration of which there is record is that of Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna (modern day Turkey). He was probably the last person to have known an apostle, having been a disciple of St. John. At age eighty-six, Polycarp was captured and led into the crowded Smyrna stadium to be burned alive. He miraculously survived the flames, requiring his Roman persecutors to finish off the job by stabbing him with a dagger.

St. Polycarp wasn’t the only early martyr who had to be killed twice. St. Sebastian, sentenced to death by the emperor Diocletian for converting fellow prisoners (and even the warden), was tied to a tree and riddled with arrows. Revived with divine help, Sebastian marched back to the emperor to call him to repentance and was finally beaten to death with clubs. Even more dramatically, after being decapitated, St. Denis, a third-century Bishop of Paris, calmly picked up his head, walked six miles, gave a sermon, and finally collapsed.

Over the centuries, accounts of saints proliferated, and Roman Catholics today recognize more than ten thousand. There are patron saints for every country, profession, and circumstance you can think of. Lost your keys? A prayer to St. Anthony of Padua might help. Love animals and the natural world? St. Francis of Assisi is your man. Seeking ecstatic union with God? St. Teresa of Ávila shows the way.

Some saints were beloved for their sense of humor. St. Lawrence, one of the early deacons of Rome, was being roasted on a gridiron when he allegedly told his torturers, “Turn me over; I’m done on this side.” Some saints could fly. St. Joseph of Cupertino, a “remarkably unclever” seventeenth-century priest, would levitate every time he heard the name of Jesus during mass, often to the consternation of his superiors. St. Christopher was seven feet tall with a dog head, while St. Guinefort was an actual dog—a thirteenth-century French greyhound revered for saving an infant from a snake.

For the first thousand years of Christian life, local bishops were charged with recognizing new saints. But as the Church grew, some of the more outlandish local saint veneration began to be embarrassing in the eyes of higher-up clergy. The need for a more standardized process became apparent, involving detailed investigations into the life and miracles of the candidate and ultimate approval by the pope. In 993, this new system for sainthood was implemented when Pope John XV formally canonized St. Ulrich of Augsburg, known for aiding women in pregnancy. In a further refinement, the Office of the Devil's Advocate was established in 1587, in a strategy to sift out all but the truly genuine miracles qualifying candidates for sainthood.

For the Protestant reformers, though, a rigorous review process didn’t address their more fundamental problems with saints. Luther rejected the idea that certain individuals had a higher spiritual status or special access to God. In a return to the New Testament concept, he taught that all people became saints through their faith in Christ—a “priesthood of all believers”—and there was no need for a special class of Christians. The veneration of saints and the practice of asking for their intercession were both condemned as unbiblical.

When Joseph Smith organized his church on April 6, 1830, it was called The Church of Christ. Four years later, the name was changed to “The Church of the Latter Day Saints,” probably to avoid being confused for Alexander Campbell’s movement, also called The Church of Christ. Oliver Cowdery wrote in editorials at the time that it was “reasonable” that God “should call his people by a name which would distinguish them from all other people.” The new name, he argued, was “meant to represent the people of God, either those immediately dwelling with him in glory, or those on earth walking according to his commandments.” And on April 26, 1838, the Lord revealed to Joseph Smith the final name: “For thus shall my church be called in the last days, even The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Verily I say unto you all: Arise and shine forth, that thy light may be a standard for the nations.”

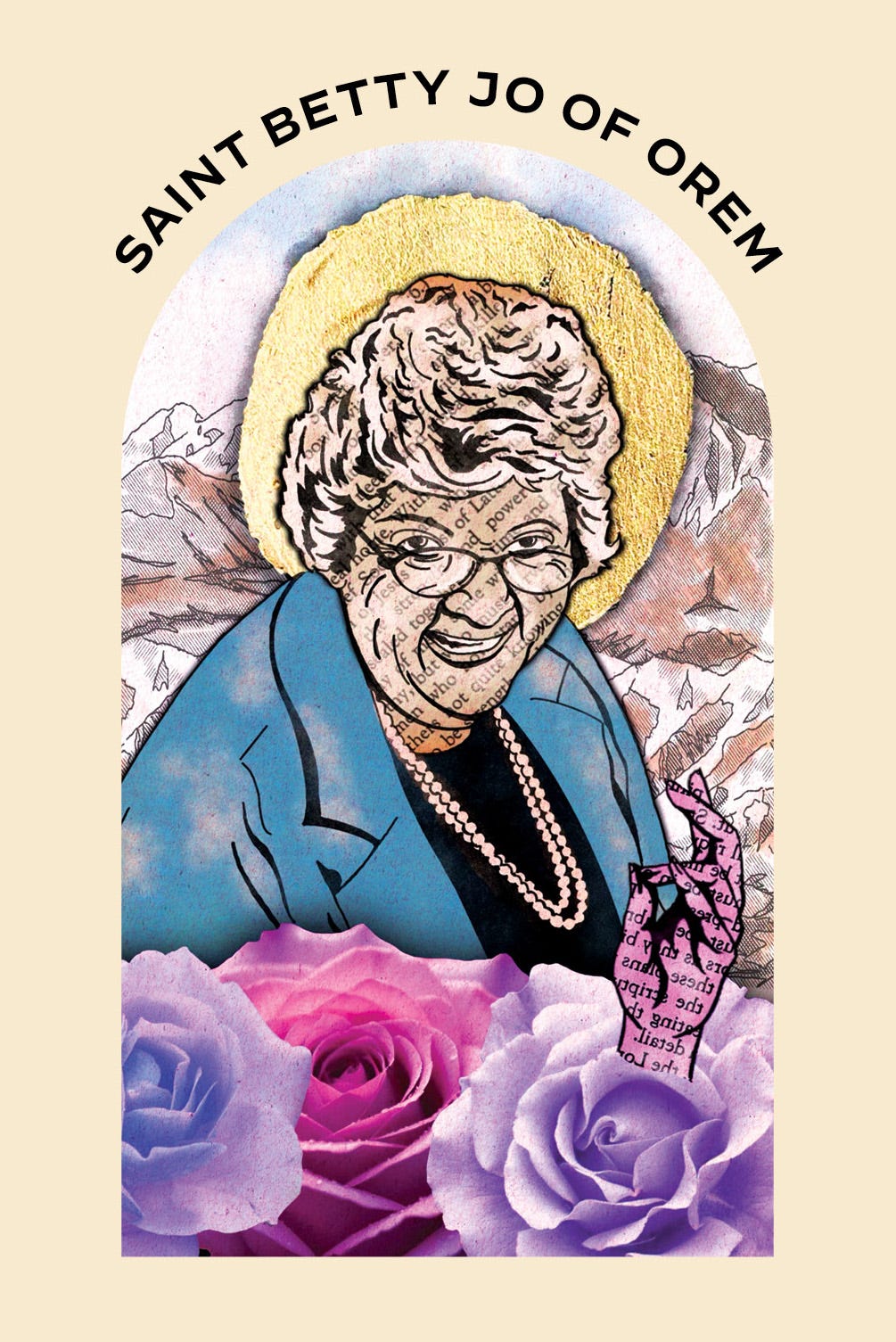

Despite our official name, only recently, thanks to President Nelson, have we begun to more fully embrace the term Latter-day Saint again. I wonder if one reason the term Mormon as a self-identifier became so widespread in the twentieth century was a lingering cultural discomfort in claiming the identity of saint, latter-day or otherwise. A wretch like me, a saint? And certainly not my elders quorum president! Even though we, like Protestants, have tried to reclaim the New Testament meaning of saints as all the members of the body of Christ, the Catholic definition still prevails in our imagination. And after all, how many people have you known in your life that you would unreservedly proclaim a capital-S Saint? In my case, probably just one, my grandmother, St. Betty Jo Davis of Orem, the patron saint of stray animals and people, someone whose love was so pure and unconditional that a single conversation could provide healing for a lifetime.

But how can ordinary disciples become more comfortable embracing our identity as saints? Let me offer one possibility. The Tyndale Bible Dictionary defines saints as “the people of the coming age.” As followers of Jesus, we are called to bring the future kingdom of God into the present. As Paul urges, saints are not people who should “conform to this world” (Rom. 12:2) but instead be willing to be set apart, to engage in the work of transforming it through love. To be a saint is to be a bridge between our time and the time of fullness.

Consider the many ways Christians throughout history have brought God’s kingdom nearer. In opposition to Roman culture, early Christians condemned infanticide, gave women leadership roles and respect, and proclaimed the inherent value and equality of every individual. In the middle ages, Christians established universities, hospitals, orphanages, and houses for the poor. In the nineteenth century, Christian activists led the fight against slavery and child labor, while in the twentieth, Jesus’s teachings on nonviolence inspired Indian independence, the American Civil Rights movement, and the peaceful dissolution of the Soviet Union. In every case, the saints transcended the problems and limitations of the temporal by embracing and partnering with the eternal.

The challenge and thrill of sainthood is to perceive and respond to the specific crises of your own age with living faith and radiant love. And heaven knows there are many latter-day needs that Latter-day Saints can address: loneliness and despair, poverty and addiction, polarization and fear, environmental destruction, and above all, a civilization-wide spiritual famine that cries out for relief.

But problems of this magnitude can’t be overcome by a single great Saint. Instead, we need a great many ordinary saints, striving together to live and model a radically different form of life, one rooted in a love beyond reason. A covenant community that seeks to nurture, embody and share the fruits of God’s kingdom: peace, compassion, forgiveness, justice, freedom, mercy, belonging. We become the saints the world needs as we link arms with our brothers and sisters in Christ, bear one another’s burdens, and together create hospitals of holy healing.

In this process of attending and responding to the world, we become the visible display of the infinite goodness of God, living windows through which to glimpse the coming kingdom.

Come, come, ye saints, no toil nor labor fear, but with joy wend your way.

Zachary Davis is the Executive Director of Faith Matters and the Editor of Wayfare.

Art by Charlotte Alba.

ISSUE 4

Below are links to all the essays, stories, poems, art and hymns in Issue 4. They are currently available to paid subscribers.

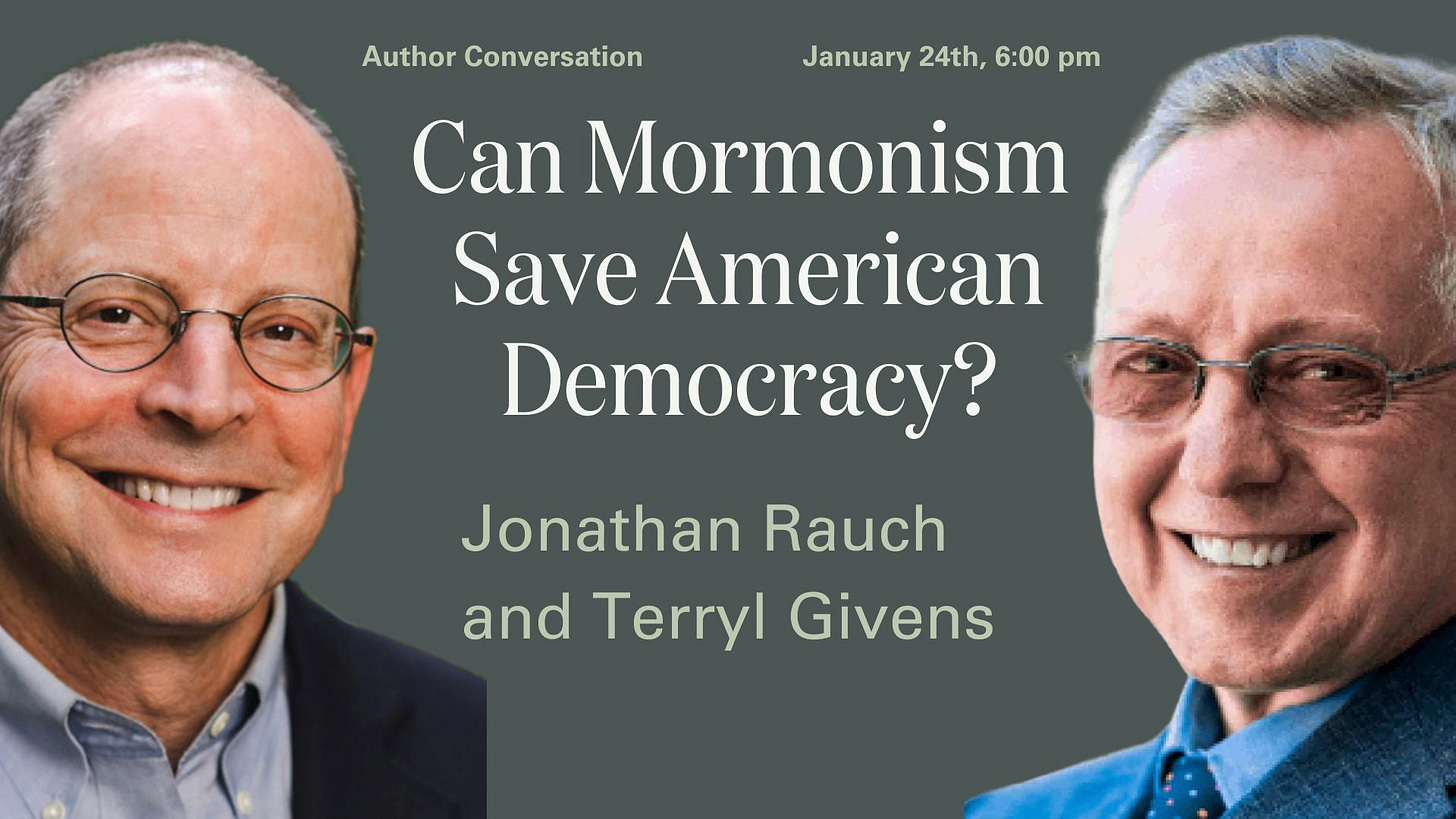

FRIDAY JAN 24TH AT THE COMPASS

Join Terryl Givens and writer Jonathan Rauch for a conversation about how Latter-day Saint theology may hold the key to healing and renewing American political life.

If Saint Betty Jo of Orem is the same Betty Jo of my youth, then I knew your grandmother. I also think she is a saint. I went to school with her son, Mark. We became good friends. I went to his home many times, and your grandmother was alway gracious and kind. When I left her home I always felt seen and heard. She was a beautiful woman and a true Saint.

Such a beautiful essay. Thank you!