The Yes, And Gospel

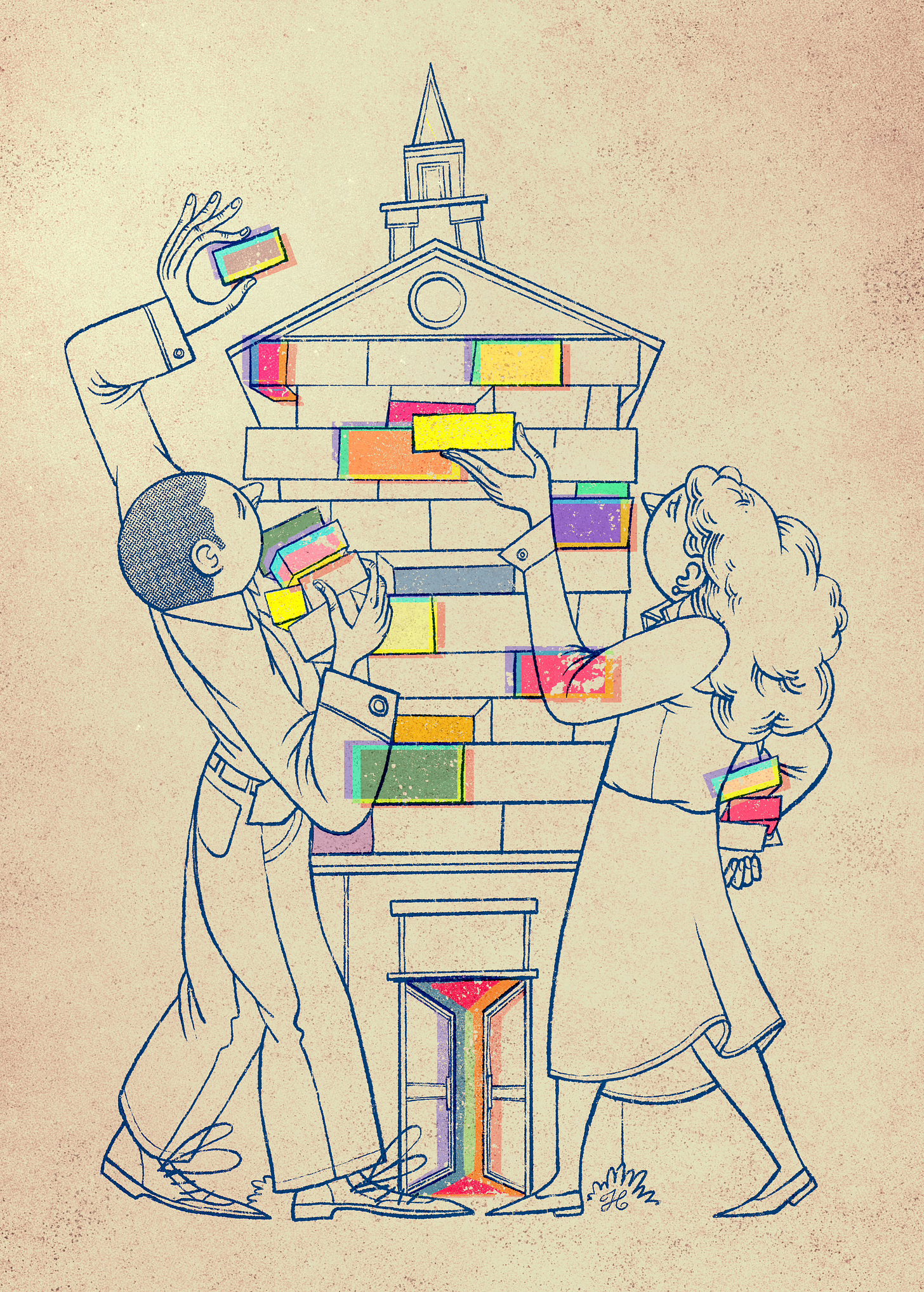

Love as Faithful Elaboration

Yes, and is the cardinal rule of improv comedy. It’s a tool actors use to keep a scene running in front of a live audience. On stage, it goes like this: An actor throws out an unrehearsed scenario or idea. For example, “Wow! I’ve never seen so many stars in the sky!” The partner in the scene then has the responsibility to agree with and build on that comment. It might be something like, “I know. Things look so different up here on the moon.” Actors continue to build on each other’s reactions, catalyzing each response with, yes, and—an agreement, and a contribution. Anything else brings the scene to a halt. As SNL veteran Amy Poehler explains, “When you’re in an improv scene and someone comes in and says ‘Doctor, the patient is ready,’ and you say, ‘I’m not a doctor. We’re in Paris. Why are you holding that baguette?’ We’re a little stuck.”

Yes, and isn’t just for comedy. The Second City, the improv theater where comedians like Bill Murray and Stephen Colbert got their starts, has a corporate education arm that teaches improv principles like yes, and for business. A brainstorming session is the corporate world’s version of the improv stage. If a coworker suggests a new pricing model, which of these responses do you think would be the most helpful?

“Yes, and we can test it against our current one to find efficiencies.”

“I’m not sure that would work.”

One is curious and open to possibilities. The other not only shuts down the conversation, it likely chills the enthusiasm of other participants.

Yes, and even works when it doesn’t look like there’s a solution. Imagine an employee seeking a raise from an employer who simply can’t give one due to budget constraints. The employer can say, “We’re not giving raises now. There’s nothing I can do.” Or she can say, “Yes, I know you deserve a raise, and even though it’s not possible now, we should talk about it.” Yes, and is about listening, validating, and making a path forward, not capitulating.

Some couples therapists encourage yes, and in their counseling, because it can help partners validate feelings and elevate difficult conversations into more positive and productive planes. Think of the tension in statements like, “We went over budget again!” or “You never help with the kids!” That tension is exacerbated with defensive responses like, “It’s not my fault!” or “I work all day!” or “What am I supposed to do?” But a yes, and response that validates and builds can ease the tension and pave the way for positive conversation and cooperative action.

Yes, and has been indispensable to me as a creative director in advertising. Most of my career has been spent in rooms with art directors trying to build on each other’s ideas. Years ago I was part of a team doing pro bono work for the National Parks Conservation Association. This isn’t an exact transcript, but our yes, and thinking went something like this:

Art director: “What if we told people our National Parks need their support because they’re so unique?”

Copywriter: “Yes, and we could highlight how irreplaceable they are.”

Art director: “Yes, and it’s not like we can just make new ones.”

Copywriter: “Yes, and if we did, they’d be these ridiculously fake replicas.”

Art director: “Yes, and can you imagine what blueprints for something like that would be?”

The final ads featured blueprints of a manufactured Delicate Arch, Yosemite Falls, and a sequoia with the headline, “It’s not like we can make new ones.” These never would have come into existence if I’d responded with, “No, I don’t think that will work.”

The more I use yes, and, the more I wish I’d been taught this thinking as a full-time missionary. I received all kinds of training on my mission. I went to mission prep classes hosted by my stake. In the Missionary Training Center, teachers paid special attention to developing skills like goal setting, building relationships of trust, and effective weekly planning. In the mission field we had regular district, zone, and mission conferences where some kind of instruction always took place. I count myself lucky to have had amazing mission leaders who taught me valuable life lessons at an early and impressionable age. But I was never specifically taught yes, and thinking. I wish I had been. Because I think it’s not only one of the most useful skills a missionary can develop, it’s native to the gospel of Jesus Christ.

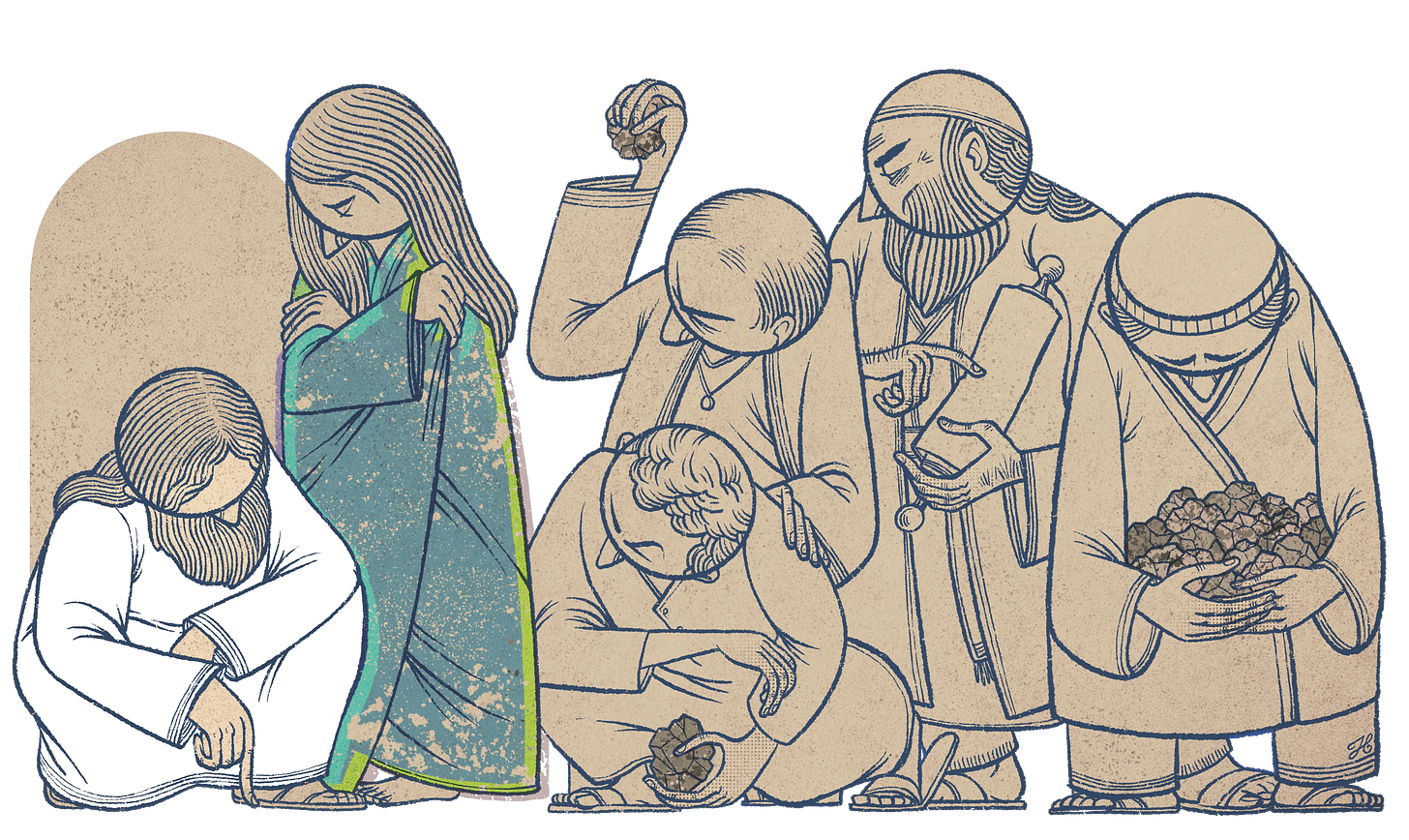

When the Pharisees brought an adulterous woman to Jesus (John 8:5, 7), they said, “Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou?” After ignoring the question, Jesus eventually answered, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.” This is a yes, and answer. Because He is essentially saying, “Yes, you’re correct. According to the Law of Moses, she should be stoned. And he that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.”

We see yes, and throughout the scriptures, particularly when there’s the potential for conflict. In the parable of the Laborers and the Vineyard (Matthew 20:1–16), when all the laborers receive their expected penny, those who had labored since early morning complain that those who were hired at the eleventh hour received equal pay. The goodman of the house tells them, “Yes, you received the payment I promised. And they did, too.” An even deeper reading might show his response as, “Yes, you all received your reward, and you are all equal in my eyes.”

In the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32), when the father celebrates the return of the younger son, the older brother is so resentful of his father’s jubilation that he refuses to participate in the celebratory feast. Note the yes, and structure of his father’s response. “[Yes] Son, thou art ever with me, and all that I have is thine. [And] It was meet that we should make merry, and be glad: for this thy brother was dead, and is alive again; and was lost, and is found.”

How might the dialogue have gone between Ammon and King Lamoni (Alma 18) if Ammon had thrown up an unnecessary roadblock by attempting to correct the king’s understanding of the Great Spirit?

26 And then Ammon said: Believest thou that there is a Great Spirit?

27 And he said, Yea.

28 And Ammon said: Well, your faith and traditions are all wrong, because God’s not actually a spirit. But I’m here to tell you the right way to think about God.

Ammon’s actual response is yes, and because he discusses with Lamoni that yes, the Great Spirit is God. And he created all things which are in heaven and in the earth.

One of the most potent scriptural examples of yes, and diffusing a tense situation is in Pahoran’s response to Moroni’s indignant epistle (Alma 61). Much has been made in Sunday School and seminary lessons of Pahoran’s humility and patience. I think we can also see elements of yes, and in his reply. Throughout his epistle he validates Moroni’s grievances (the yeses). He also builds on the conversation by giving him news that puts those grievances in context (the ands). His message might be best encapsulated by verse 9: “[Yes] in your epistle you have censured me . . . [and] I am not angry, but do rejoice in the greatness of your heart.”

One of the reasons yes, and is so compatible with the gospel is because it is so incompatible with an “us versus them” mentality. Yes, and is about collaboration, not confrontation. And who in this faith faces potential conflict on a daily basis more than our full-time missionaries?

During my time as a missionary in Eastern Europe, elders often visited a woman who had been a member of the Church for about a year. During one visit, she openly lamented the loss of her Catholic traditions. For decades she’d attended mass, taken communion, lit candles, and gone to confession, all surreptitiously and in defiance of an oppressive Soviet regime. Now, a baptized and confirmed member of a faith new to her and her country, she was missing the familiar and comfortable genuflection, the sign of the cross, rosary beads, and the aroma of incense.

To my shame, while she was sharing her grief, I rolled my eyes in exasperation. She called me out for it and said other elders had responded similarly. I wasn’t the first to lose her trust when I told her she should just embrace the restored gospel and not worry about her old traditions. I saw her faith traditions as something to confront, not collaborate with.

I was an inexperienced twenty-year-old whose prefrontal cortex was still in its final stages of development. But what if as part of the training I’d received, I’d been instructed in yes, and exchanges? What might have happened if I’d had the insight to say, “Yes, there is great beauty in those ceremonies and rites. And here is how we see ritual and ceremony in the Restored Church . . . ” Or “Yes, traditions are important. And, I’d love to know how they bring you closer to Christ.” Or “Yes, I understand your Catholic upbringing is dear to you. And, have you noticed similar themes in the Book of Mormon?” There is no end to and. That’s what makes improv so captivating. It might not have resolved her concerns. But it would have kept the conversation going. And it would have been another step towards Christ for both of us.

President Gordon B. Hinckley often extended this invitation to members of other faiths: “Bring with you all that you have of good and truth which you have received from whatever source, and come and let us see if we may add to it.” This is a yes, and statement. He was affirming and adding, saying, “Yes, you have truth in your faith traditions. And we invite you to discover more with us.”

A few years ago, I was out with the missionaries assigned to our ward. We went to a house where they said they’d been invited to drop by. Whether it was a mistaken address or a bait-and-switch contact, the owners of the house did not let us in, but immediately launched into an evangelical rant against the Church. They accused the missionaries of spreading un-Christian doctrine and backed up their accusations by citing the first verses of John from memory: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not anything made that was made.”

They paused, giving the missionaries a chance to respond. Still reeling, one of these stunned elders simply stammered, “But . . . we’re here to share the Book of Mormon.”

Now, I was as shell-shocked by our reception as these elders were. I was no help at all. But what a missed opportunity. We might have said, “Amen! Praise God! He is the Word!” Despite the hostility, these people offered something we were in complete agreement with. There was no reason to follow that beautiful scripture with “but . . .”

If we’re not listening, if we’re too eager to say what we want to say, yes, and doesn’t work. Amy Poehler says when you change the script to stick with your own agenda, “it shows someone’s not listening. They don’t go along with your initiation. They, in the moment, want to correct you. And also you can’t trust them.” Building relationships of trust is not simply nodding our heads. It’s listening. Then affirming. Then contributing. We never take any of those steps if we confuse conversations with sermons.

In Yes, And: Lessons from the Second City, authors Kelly Leonard and Tom Yorton assert that practicing improvisational skills “improves emotional intelligence, teaches you to pivot out of tight and uncomfortable spaces, and helps you become both a more compelling leader and a more collaborative follower.” We could all use those skills. But the need for each of them is intensified with the rigors and challenges of full-time mission service. Leonard and Yorton also say, “Work cultures that embrace Yes, And are more inventive, quicker to solve problems, and more likely to have engaged employees than organizations where ideas are judged, criticized, and rejected too quickly.” If I were a mission leader, this is exactly the kind of culture I’d want to nurture in the mission. And I’d use yes, and training to help us get there.

I haven’t been a full-time missionary for decades. But I still have faith-based and faith-laced conversations all the time. And yes, and thinking is the most productive and warmhearted approach I’ve found for discussing religion, no matter who I’m speaking with. I recently went to lunch with a friend and coworker. When our meals arrived, he said he’d like to ask a blessing on the food before we ate. Of course I said, “Yes.” And after his prayer, I was conscious of following up with several ands. I asked him how he feels God’s love in his life. I asked what miracles he sees. I asked his favorite scripture. I didn’t have to use the conjunction and. But together we were furthering the conversation, when we could have just as easily changed the subject.

Even with someone whose beliefs are antagonistic to mine, I can find a way of saying, “Yes, I think I can understand where you’re coming from.” That’s a major connection, whereas “No, you’re totally wrong” simply throws up a wall, leaving me on one side, and them on the other. Us versus them is a barrier we construct ourselves.

Sometimes those barriers we erect are against ourselves. When I was a bishop, members would often come to me with what they perceived as worthiness issues. In these cases, it would have been profoundly detrimental for me to say, “Well, you shouldn’t take the sacrament because you’re not worthy.” Yes, and helped me stay intensely set on validating and moving the conversation forward. I might have said any of the following:

“Yes, you’ve done something you wish you hadn’t, and the Savior says over and over throughout the scriptures His hand is stretched out still.”

Or “Yes, you’re feeling low right now, and in D&C 58:42–43 the Lord says He is willing to forget this completely.”

Or “Yes, that’s a serious issue, and you’re amazingly brave to be open to talking about it.”

Or “Yes, I see why you feel you’re not worthy to take the sacrament now, and did you know the General Handbook says, ‘Partaking of the sacrament is an important part of repentance. It should not be the first restriction given to a repentant person who has a broken heart and contrite spirit’?”

Again, there is no end to and.

Yes, and is the golden rule of improv. But it is also the hidden subtext to our most Christlike interactions. We are all collaborators on this mortal stage. If we’re willing to listen to our fellow actors, hear their prompts, repress our personal agendas, and respond with yes, and, we can all move the scene forward together.

Greg Christensen is a writer and creative director.

Art by David Habben.

JOIN US

Wayfare Issue 5 Release Party

To celebrate the release of Wayfare Issue 5, please join us for a gathering on Friday May 2, 7pm at The A-Frame in the Provo Tree Streets. We’ll have freshly printed issues, readings, food, and friendship. We hope you can join us! Please RSVP below.Become a subscriber!

Mother Tree Author Talk & Book Discussion

Join us on May 8, 2025, at 7 PM MDT for a discussion of the power of the Divine Feminine as we conclude our reading of The Mother Tree. Author Kathryn Knight Sonntag will share her thoughts on the increased relevance of her book in our current cultural moment. Participants will be able to offer their own insights and raise questions about the themes of …

May 8, 7 PM MDT via Zoom

Pilot Program

What if you were called to serve in the restoration of polygamy? PILOT PROGRAM is the story of Abigail Husten, a writer and professor whose life is turned upside down when she and her husband Jacob are called to participate in a pilot program restoring polygamy to current LDS practice.

April 30th, 7pm at The Compass

KEEP READING

Communion and Consciousness

Is sorrow the true wild? And if it is—and if we join them—your wild to mine— what’s that? For joining, too, is a kind of annihilation. What if we joined our sorrows, I’m saying. I’m saying: What if that is joy? —Ross Gay

Holy Records, Unholy Record-Keeping

Adapted from Redeeming the Dead, by Amy Harris, in the Maxwell Institute’s Themes in the Doctrine and Covenants series

There is no end to "and." Wonderful thoughts here.

I love this piece.