Breaking My Face

What Is Life When the Self Rises Again?

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin wrote that “everything that rises must converge.” He imagines ascending in love and wisdom until we find ourselves at the summit of existence surrounded by those devotees of goodness from all walks of life who have climbed the same radiant peak, delighted by the community of the consecrated. Lehi intimated that everything that will ultimately rise must first fall: “Adam [and Eve] fell that [humanity] might be, and men [and women] are that they might have joy.” (2 Ne. 2:25) In order to participate in the communion of the joyous, we must begin below. Sometimes the ascent to joy from our mortal fallings demands fierce determination and grace.

As a teenager of modest means, I often found myself with my friends in the backcountry of our local mountains on a snowy afternoon, scaling a slope to catch a free ride on our snowboards. The winter sun multiplies its brilliance as it reflects off the expanse of a white mountainside. An invigorating peace breathes through those high places. One day, after almost a foot of snow had fallen in the valley, we drove up the canyon with our boards. We laughed in the light as we hiked through knee-deep drifts, then we rode the fresh powder to the base of the glen. The ethereal feeling is difficult to describe, but it lies somewhere between floating among cumulus clouds and catching hold of the coattails of God. You feel invincible and weightless.

After our first run, my friend suggested we climb to a small cliff we had jumped before. It was a slight escarpment of eight feet or so that merged at the bottom with the slanting mountainside so that once you landed you could continue riding downhill. Infused with the ecstatic sense of buoyancy from our powder ride, I hiked to a spot above the cliff and headed straight down without much carving to manage my descent. When I hit the lip of the jump, I lost control and didn’t land with my board parallel to the ground as I intended. I don’t remember too much about that fall, but my board turned perpendicular to the slope and sunk into the soft powder where it stuck fast. My feet planted, but my face kept falling. My knee came up to greet my face with an abundance of enthusiasm. I think I can still remember the sound of the crunch. When I came to my senses, my friends were searching the bloody snow for my teeth.

In time we found the teeth still inside my mouth, dangling from the roots hanging from my broken maxilla, the bone that normally holds your teeth in place. I refer to that as the day I broke my face. I broke my nose and my jaw. My lower teeth went through my lip—all the way through. One trembling and loyal friend shot down the mountain on his board in search of help. He found a snowmobiler who came as far up the mountain as he could. Two other friends carried me between them and helped load me on the back of the snowmobile. I remember apologizing for bleeding on the man’s coat. He told me to please not worry for blessed heaven’s sake and to hold on. He took me to a ranger station. The ranger called an ambulance and provided first aid. I remember the long wait for that ambulance as bloody paper towels accumulated at my feet. The shock wore off. When the paramedics arrived, they gave me an injection of something wonderful and thick which carried me off into beautiful oblivion.

I awoke in the hospital after reconstructive and plastic surgery (I often tell my students that stunning looks like mine don’t come naturally), and my parents took my puffy face home to rest. I couldn’t eat for weeks, instead shooting instant breakfast shakes down my throat with a water bottle. To fix my jaw, the orthodontist installed a device that might have been invented by Dante himself to punish the purveyors of orthodontia. It was called a Herbst appliance. It was essentially two metal, telescoping bars on the insides of my mouth to keep my jaw straight as it healed and to push my teeth forward. It dug into my cheeks. It came unhinged if I laughed or yawned, and then it would either get stuck open, making it impossible to close my mouth, or it would separate and stab the roof of my mouth. Life was deluxe.

The orthodontist promised that the charming contraption would be removed after six months. Over a year later, it was ready to come out. As I sat in the chair, mouth agape, the orthodontist began digging around with something that looked like pliers pulled from a toolbox. He paused mid-twist and asked if I had premedicated. Nobody had told me I needed to take amoxicillin, but the orthodontist assured me it was important and offered to write me a prescription. It seems a small thing in retrospect, but I was a teenage boy with testosterone raging through my lithe frame, and I was frustrated. I thought I would go fill the prescription and return within minutes, but the doctor told me to set an appointment to return. When the smiling receptionist told me it would be ten days before they could get me back in, I began seeing red. I had heard of blind fury, and my vision began to blur. I stalked out the door, trying to slam it behind me, but it was one of those pneumatic doors that can’t be banged shut. I slammed my car door and drove home yelling at all the other cars I couldn’t see through the rage blur, yelling at heaven, yelling at the orthodontist. It was only ten days, but it felt sempiternal to me.

When I got home, my perennially kind mother opened the door from the house to the garage to celebrate with me the removal of this piece of metal. She was unprepared for the feral creature that greeted her, snarling and howling. “What’s the matter, Robb?” she asked. “Look in my mouth!” I yelled. I stormed past her and stomped to my bedroom, where I searched for something to break. I unplugged the computer monitor on my desk and began carrying it outside. My mother followed behind me, asking tentatively, “Robb, what are you doing?” I could still hear her baffled, “Robb? Robb?!?” as I swung the computer around my head by the cord and smashed it into the concrete patio. It shattered with a satisfying explosion, scattering glass and plastic. Can it be that my mother asked if that made me happy? I can’t remember. But I needed to go for a walk. I remember growling and grumbling at cars as I walked toward a corner store not far from my house. As I went in to purchase a fruit drink—a kiwi-strawberry Mistic, specifically—I was muttering my incoherent frustration, “Premedicate . . . Nobody told me . . . Ten days . . .”

There in the corner store, I paid for my drink, my hands shaking in anger. I opened the bottle and looked at the underside of the lid where I found the following message grinning back at me: “Happiness is a decision.”

Two quick options flicked through my mind: either I hurl the bottle through the store window, shouting, “Happiness this!!” or I surrender my anger to humor. Ironic humor, in this case. Very, very ironic. A vision entered my mind of God, beaming from ear to ear, calling over an angel in heaven, handing over the bottle of kiwi-strawberry Mistic and saying, “Please get this to that grumpy boy down there.” I imagined the angel maneuvering the drink into place just before I grabbed it. I began to laugh. “Happiness is a decision.” Fallen things rising in joy. Every day, life asks whether we want the way of gladness or some other way. Ascend the peak. Greet the joyful.

Joy is our inheritance as children of Heavenly Parents who delight in our existence. Heber C. Kimball affirmed, “I am perfectly satisfied that my Father and my God is a cheerful, pleasant, lively, and good-natured Being. Why? Because I am cheerful, pleasant, lively and good-natured when I have His Spirit. . . . He is a jovial, lively person, and a beautiful man.” God’s joyfulness is our birthright, but we use our agency to live in the gift. Paul makes joy a verb: “We joy for your sakes before our God” (1 Thes. 3:9). Joying is something we deliberately enact. We live the gladness of God.

I have learned that there is a method to choosing happiness. And joy comes more easily to some than to others. Researcher Sonja Lyubomirsky acknowledges that genetics play an important role in our “happiness set point,” noting that 50% of our happiness is genetically determined, 10% is circumstantial, and 40% derives from intentional activity. But she affirms that “just because your happiness set point cannot be changed doesn’t mean that your happiness level cannot be changed.” We can choose to practice gratitude, mindfulness, deepening relationships, compassion, and service. In short, we can practice choosing happiness.

Thomas Merton writes, “No despair of ours can alter the reality of things, or stain the joy of the cosmic dance which is always there. . . . We are invited to forget ourselves on purpose, cast our awful solemnity to the winds and join in the general dance.” Sometimes I wonder, what would happen if God started laughing? A depth—a resonance—as clear and as ebullient as a river, so deep and so joyous we could barely swim in it. Awash with laughter, we’d splash in God’s mirth. What if God started singing again, “Let there be light”? And we, oh loves, like Lazarus would wake up clear-eyed and refreshed, able to see as we are seen and sing as we are sung. God who sings the sunrise new each morning brings the dance to our eyes as well: an awakening with this outpouring of grace—an arising. What if God started dancing? And the whole world, no longer stooped in stupor, joined the bright dance, remembering we worship Joy. Reinhold Niebuhr asserts, “Humor is a prelude to faith; and laughter is the beginning of prayer.” There could be more joy in our worship, more laughter in our prayers. Rather than wringing our hands that the cart is toppling, we might dance like David before the radiant ark of the covenant.

Sometimes the joy chooses you. When he was three years old, my son Oliver and I were at the park playing together. I took a stick and wrote his name in the sand. Then he started dictating letters to me and I would write them: "O. G. F. E. F. O. What does that say?" "Ogfefo." "Is that a real word?" "I think you just invented it." His eyes got big. "So I own it!" "Yeah, you own it. It's all yours." He spelled a bunch of others. He was getting excited, "I own five words!" He was fairly hopping about. Then he spelled, "FEO. What does that say?" "Feo." "Is it a real word?" "Well, not in English, but it's a word in Spanish." "Oh, so I don't own it. The Spanish people own it." Raise your arms and give thanks, grinning. The joy chooses you.

To choose joy is not to live in blindness to the anguish of human suffering, but it is to determine not to be undone by the pain that abounds and to strive to see the golden thread of beauty that persists in our darkness. Once I received a phone call late in the evening from a friend. I could barely decipher through his grief-choked words that he wanted me to come to the hospital. When I arrived, this giant of a man fell sobbing into my arms. “He’s not going to live,” he said. He and his wife were expecting their second child, a son. She was in the next room, about to give birth to this baby boy who would not live more than an hour according to doctors. He had no kidneys. We cried and prayed together. When the baby came gasping into this world, holding on to life through his mom’s umbilical cord, my friend took his son into his hands, and with a small group of men who loved this man and this boy, blessed the tiny infant. He tearfully gave the baby his own name, expressed love and gratitude for his birth and his existence, begged him to remember the family, to watch over them as he passed back into a life other than this one, and was silent. Baby James lived an hour and a half. His life was defined by love. Could there be a kernel of joy to be found and planted in the communion of those who gathered in love? Is the beauty of connection a source of our gladness?

Are love and joy the same thing? Or at least close relatives? There were small moments of gladness that night, the products of a mother’s fierce faith and a father’s gentle hope. When James passed away, this baby’s father asked us to give him, the father, a blessing. We laid hands on his head and expressed love and gratitude and hope, and we promised joy. As I drove home alone, I wept. I wept for sorrow, yes, but also for the sacred privilege of witnessing in two short hours two holy transitions: from light to love to light again. The twin miracles of entering and exiting this remarkable sphere of existence where we are that we might have joy. His brief life was charged with heartache and hope and holiness intermingled and interwoven, like the life of Christ: a God made man for an instant. A God who came to experience all our sorrows and sanctify them into wisdom, compassion, and growth. They say that those who die and return to life long for death again, yearning to drink light again—to taste color. But I can imagine this bright beautiful boy stepping from that circle of love back into the light of divine love and longing too—yearning for the feel of father’s hands and mother’s lips, the mortal sound of sister’s laugh. Oh, we ache because we love. And we hope, eternally we hope that fallen things will rise again. That joy will have the final word. That seeds planted will one day shoot up as majestic trees ripe with fruit. That sorrow comes forth from the grave as something else entirely. That nothing bad is permanent. That only joy is eternal.

Beyond the cliffs that break our faces and the deaths that break our hearts, there are, of course, minor falls. Several years ago, I sat on the front porch contemplating the songlessness of entropy, the way the weeds creep and crush and encroach on my garden, my lawn, my flowerbed; the way the messes multiply and replenish in a family with five children. There’s a certain dark miracle there in the relentless march of chaos and mayhem. It can sink into the soul and weigh you down.

But here’s the point: That late summer afternoon, I looked up to see the stumbling, toddling, mad amble of my beautifully round fourth-born making her way across the grass, barefoot as a Carmelite, holding the hands of her two oldest siblings who gazed at her with reverent attentiveness. She was not yet two years old. This small child has oceans in her blue eyes. There are constellations and congregations of solemn clouds swirling behind her piercing glance. Ellie crouched at the edge of the green lawn to examine a rock. She made a wondering sound. The three older children all joined her in her genuflection toward the stone. They each touched it in turn with gentle affection. Then Ellie shot up and pointed exuberantly. The neighbor dog had come wandering into her consciousness. The children admired with her. She bent for a snail. They dropped to their knees. And I wanted to join them. Isaiah says that in the Millennium, when there is peace among all creatures, when the wolf and the lamb bound recklessly down grassy slopes, joyously united, and the lion and the ox share a communal feast of straw, that a little child shall lead them. I wanted to follow this child into a world of miracles, a world of wonder, light, and joy. My sinking heart began to lift inside my old dad chest, began to soar away from the pull toward despair and discouragement and to rise toward something sacred, toward joy. Joy is the light beneath all darkness, the music at the heart of all silences. We watch for it, listen attentively, choose gladness. “Joy is the infallible sign of the presence of God.” We can see God. Here. Now. In this moment. And the joy will come.

Can we listen for the sound of God laughing and watch for the joy at the heart of existence? Everything that falls must rise. Everything that rises will converge in the joy of God. Even Christ was planted in the earth before bursting forth from the grave, radiant to save. Come find me on resurrection morning. I’ll be sitting on my front porch, joying. Then we’ll rise, together.

Robbie Taggart is a teacher and poet who delights in the holiness of the everyday.

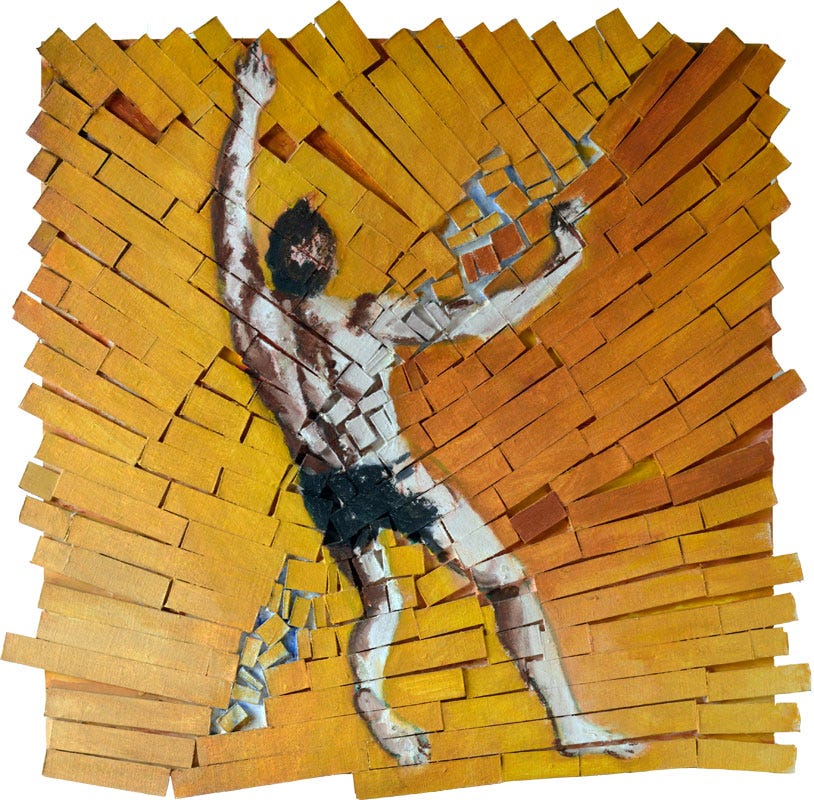

Artwork by Nicholas Stedman.