When There is No Cross To See

When I stepped into a dark chapel in Navarrete, Spain, I didn’t expect to see so much gold. The altarpiece was an expansive display of intricate metalwork framing images of Christ, and the glinting gold reflected a distinct brightness. I removed my backpack and sat on a bench, looking up to the crucifixes and cherubs which adorned the ceiling, as other pilgrims came and went. Each time the wooden doors of the chapel eased open, I heard quiet exclamations followed by silent awe. None of us had expected this small earthen town rising above endless grapevines to hold such artistry, reverence, and adoration.

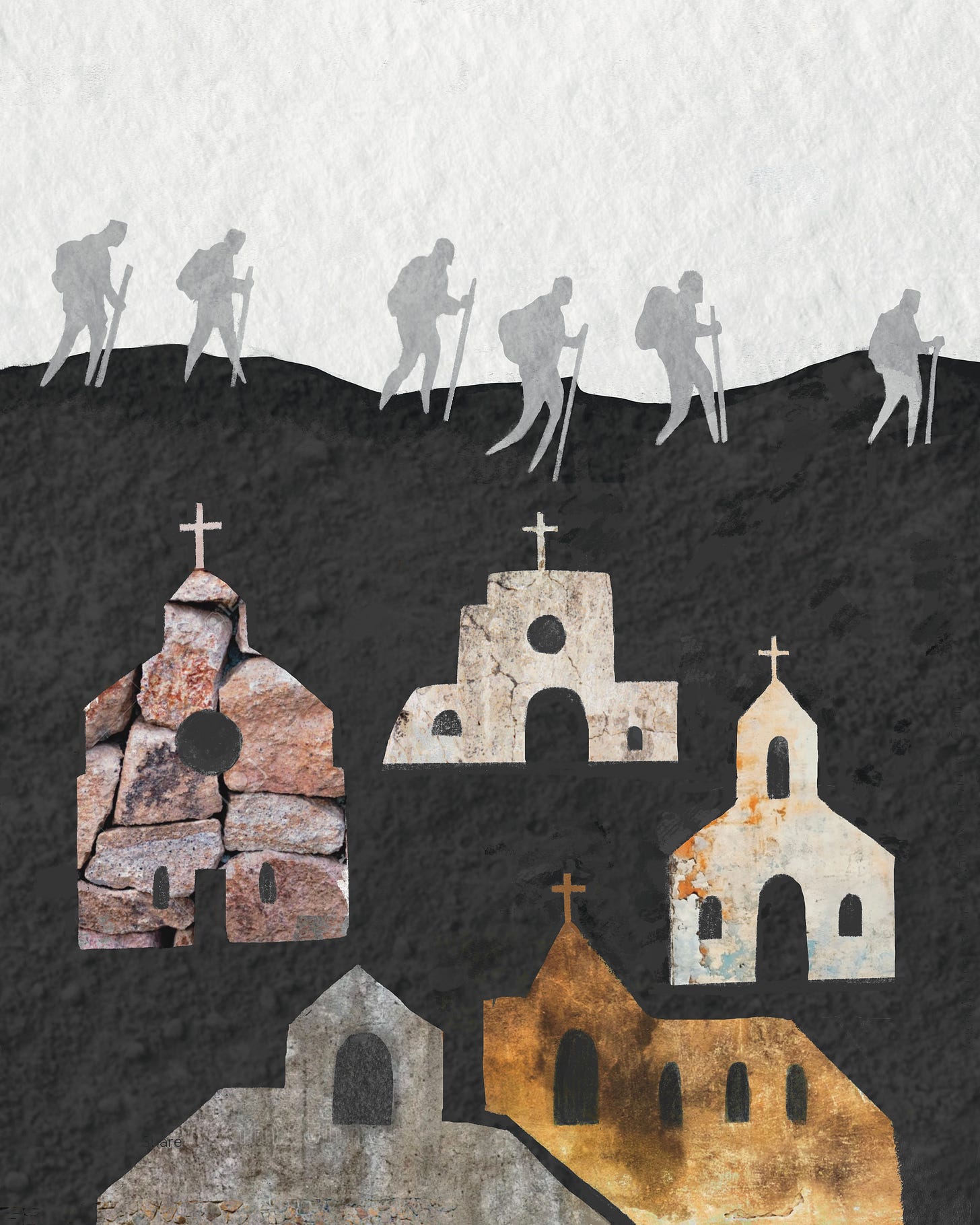

For centuries, various routes of El Camino de Santiago have led pilgrims towards the Catedral Basilica de Santiago de Compostela, the traditional burial place of St. James the Great, located in the northwest corner of Spain. Today, people of many faiths follow paths marked by shells and yellow arrows which wind through hills of grapes and sunflowers, flat desert stretches, modern cities, near-empty villages, and mountainous greenery. The symbol of the cross forms an integral element of the landscape and remains a constant even as the scenery changes. Pilgrims are met by simple sticks stuck through wire fences in the shape of the cross, stone-carved crucifixes welcoming pilgrims to new regions, and wooden crosses raised high against every horizon. These markers make it impossible to travel even one mile without remembering Jesus Christ.

Growing up, many of my elementary school field trips were visits to Spanish missions along El Camino Real, a trail of Catholic faith along the coast of California. These places always held a sort of dark mysticism for me, and my memory is full of images of candle-lit pews and childish games of breath-holding as we tiptoed past the chapel graveyards.

During Sunday School lessons on the Atonement of Jesus Christ, I recall hearing teachers explain that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints doesn’t use the symbol of the cross in a way that made the cross seem almost forbidden, an image that should be avoided. It seemed to me that, in an effort to differentiate the restored gospel from other historical Christian traditions, any differences were used to point out flaws in the faith of others, rather than to praise people’s innate desire for the sacred.

One day as I walked the red dirt road leading into Astorga, a city near the end of an interminable desert stretch of the Camino, a fellow pilgrim asked me, “So, what do you think about God?” In the conversations I’d held with other pilgrims, hardly anyone had so readily brought up the topic. This man explained that his decision to walk the Camino had been extremely last-minute—mere days after asking a priest at his local church if he thought doing so would be a good idea, he’d started walking towards the alleged grave of St. James.

In an effort to answer his question about God, I described an experience I’d had in Burgos, a city I had passed through earlier on my journey. The cathedral there was of a gorgeous gothic design, blindingly bright in the sun, and heavily embellished both inside and out. In direct contrast to the overall beauty, within a small chamber off the cathedral’s cloister, I’d found a sculptural depiction of Christ that made me reexamine the symbol of the cross. Unlike the many uplifting depictions of the resurrected Christ that had graced the walls of my church growing up, and contrasting even with the more somber paintings of His sufferings in Gethsemane and His death on the cross, this crucifix was gory. There were splatters of blood and a darkness under the skin that clearly communicated tangible suffering. The physical realness of the cross and Christ’s corporeal pain were made achingly clear, making me feel a sadness and despair in the face of death that the paintings in my childhood church had never approached.

Every day along the Camino I observed the physicality required to move and the quickness with which health and vitality can disappear in the aging bodies of pilgrims older than I. So far in my own life, I had experienced levels of physical pain and discomfort—strained muscles, a broken bone, grievous sunburn, sickness, exhaustion—but no matter the severity of those sensations, nothing had come remotely close to the pain that accompanies actual death. It was a concept inconceivable for me to conceptualize. Meditating on the impossibility of life after death, of peace after suffering, of movement after definite stillness, I felt a greater need to believe in the miracle of Christ’s Atonement. The crosses dotting my horizon each day became reminders that belief in the incomprehensible bad is what makes room for belief in the unimaginable good.

As we continued walking together, the man told me, “I came here wanting to connect with God, but I’ve been connecting more with people.” I replied, “Those sound sort of the same.”

In my conversations with other pilgrims, I found that most people were walking the Camino because they wanted a change in their life or weren’t sure what they wanted to do next. A man from Italy told me that he was walking because he and his friends had pledged either to have a child or walk the Camino by the time they reached the age of thirty, and he’d chosen the Camino. A woman from Slovenia wanted to live with greater purpose and hoped to find that purpose on a winding trail through Spain. Another woman carried not only her own prayers but the prayers of friends and family; she walked on behalf of all who knew she was making the pilgrimage, hoping that her arrival in Santiago would bring desired answers and miracles. While my brief encounters with other pilgrims didn’t make me privy to all the painful details of their lives, we always voiced our hopes. Each person that I met became a symbol of confidence, sureness, and trust as we cheered each other on.

My personal reasons for walking the Camino included a desire for physical challenge, as well as uncertainty about my future plans. Spending the majority of my time outside and passing constant reminders of Jesus Christ in the shapes of crosses and cathedrals quickly pointed my thoughts toward the spiritual, but that hadn’t been my initial purpose. I soon realized that I had left my home in Utah, a desert full of churches, in search of unfamiliarity—only to find myself in another desert full of churches, albeit of a different tradition.

I laughed at myself when I realized this irony, sitting in the dark chapel in Navarrete, looking up at gold and crosses and figures of Christ. Both the Latter-day Saint and Catholic traditions hold harm in their histories; I knew that no organization that claims to follow the teachings of Jesus Christ does so perfectly. The missions I’d visited in California were proof of bad being done in the name of God, as the Spanish forced the Indigenous peoples to adopt the practice of Christianity; the circumstances complicating my current feelings about religion are proof of hurt still being inflicted today. But on the Camino, as an outsider observing the landscape of another religion, and removed from my own faith’s largest gathering places, this harm and hurt fell away—not into oblivion, not gone without reckoning, but crowded out by the enormousness of Christ and the goodness of individuals.

It was raining on the morning I set out from Sarria, a city located about one hundred kilometers from the Camino’s end. Also starting from Sarria that morning was a group of Spaniards dressed in brightly embroidered clothing. They were fresh and energetic, clearly embarking on the first day of their journey. I passed them as they gathered to pray outside the walls of a cemetery, and after walking down a steep hill, I paused to watch them descend together—a pipe player leading them at the front, their exuberant brightness breaking out in gallops and shouts of song.

I clapped along with the piper’s music as they neared, and one of them pointed at me with a smile. “You dance!” he commanded, so I did. People crossing a bridge pressed to one side to let us pass, skipping and mud-splashing to the notes of the pipe. The dancing man said to me, “When there is darkness in your mind, you continue dancing. When there is blood on your feet, you continue dancing.” His instructions continued as we danced down the trail, each time ending with the same words: you continue dancing. He finally slowed and looked in my eyes to ensure my complete attention. “No matter what happens, when we hear the music, we continue dancing. That is el propósito. The purpose. You understand?”

As I walked on, the piper’s music growing soft behind me, my fingers twirled in the air when I couldn’t dance with my feet. I saw the group a few more times throughout that day, and they were always full of song, full of dance, full of encouragement for the strangers they passed. It was clear that their purpose was to have so much joy in their journey that anyone they met would have no choice but to smile. They were a source of unimaginable good for so many pilgrims who were beginning to suffer after weeks of physical and mental exertion.

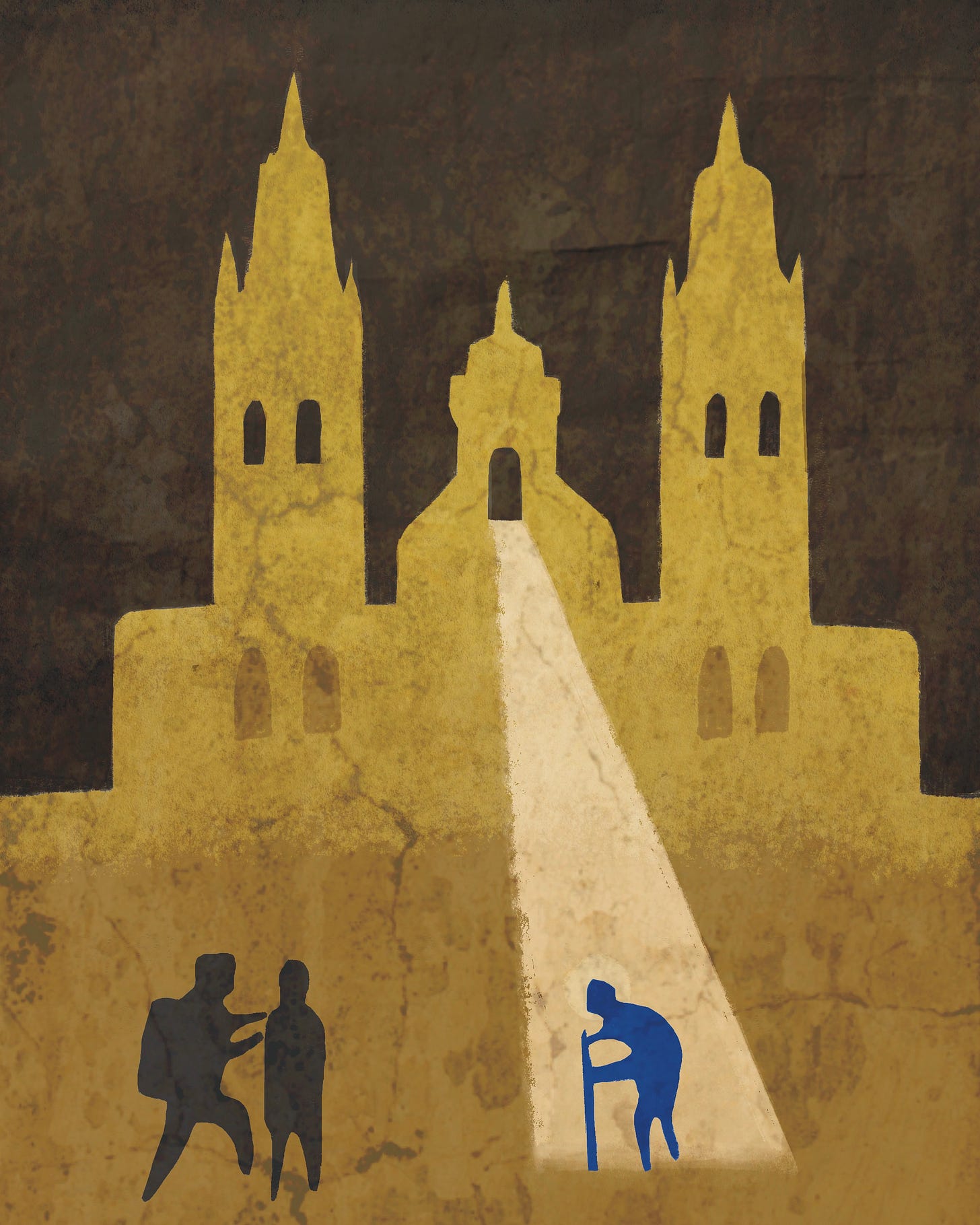

Clouds parted as I reached Santiago de Compostela after days of cold rain. I walked into the cathedral’s plaza alone and sat in the center, resting on my backpack, watching other pilgrims stream in from all sides. They came through the tunnel with the constant song of bagpipes, out of streets filled with souvenir shells and sugar-dusted cakes, and I realized that I recognized a surprising number of them. I waved to some and watched others wave to the people they saw and recognized—a widely woven net of knowing. One man in a blue jacket caught everyone’s attention: he leaned heavily on his walking sticks, so dependent on them bearing his weight that he eventually fell to his knees. His hands moved between his tearing eyes and too-big heart. No one knew what he cried for, how long he had walked, the prayers he’d carried, or the solace he might have been seeking. We only knew that he knelt in worship of the God who had miraculously brought him there, and in watching, we worshiped with him.

The next morning at pilgrim mass, I watched the priests swing the botafumeiro through the transept, incense rising like sacred whispers to heaven. The smoky air, Latin song, and rain-darkened windows distilled that same medieval mysticism that I have always associated with Catholicism. As I stood to accept the small sacramental wafer, I thought of the unthinkable faith it must take to believe in the literal doctrine of transubstantiation—but then, there is unthinkable faith required to believe in anything. I looked around at the other pilgrims, a majority of whom also appeared to be guests in this faith ritual that we had all chosen to take part in, wondering what miracles they’d been hoping for and how many of us had been those miracles for one another. A woman next to me pointed at the priests and whispered, “It used to make me so mad knowing only men could do that, and it still does, but now I try to feel compassion for them, like Christ would. They are only trying their best in a system that isn’t perfectly fair.”

I spent the rest of that day watching pilgrims arrive in the plaza and wandering past shops selling shells and crosses: reminders that I had come to the end. But the end, once I left it, would become a meridian. Like the cross of Christ, which caused His death and necessitated His resurrection, all other finalities must be passed through and remembered. In the plaza, looking up at the spires of crossed metal, I mourned the loss I’d soon feel when that symbol would cease to occupy so much of my daily view, when there would be no cross to look at.

As rain clouds darkened, my eyes fell from heaven to the slick ground beneath me, and I followed others to the safe dryness of the bagpipe tunnel. We pressed close, strangers making room for each other, laughing and unalone. Each body surrounding mine loomed large and real and alive. Their hearts pumped blood I could not see, held joys and fears I could not name. We all surely held beliefs and prejudices that, if shared, would clash in contradiction, but for many of us, our linguistic limitations prevented such complications. Up close, breath to heaving breath, we all just needed air. This desperate demand distilled the gift of the cross into each person’s being and illuminated the simplicity that grew in its wake. Christ’s aliveness would be our livelihood, His miraculous contradictions the anchorage of our covenants to take care of each other without judgment or retribution. This was the dance we would continue dancing while looking up to heaven and out at each other; full of darkness and blood, yes, but heartened and looking for every wave of light. Our purpose was simply to continue existing together and the cross of Christ made it so.

Fleur Van Woerkom is a lover of earth, art, movement, and stories. She is currently studying writing at Columbia University.

Art by Sarah Hawkes.

KEEP READING

EVENTS

August 2: Pilot Program at The Compass in Provo, UT

PILOT PROGRAM is the story of Abigail Husten, a writer and professor whose life is turned upside down when she and her husband Jacob are called to participate in a pilot program restoring polygamy.

When: Aug 02, 2025, 7:00 PM

Where: The Compass, 250 W Center St Provo, UT

August 6: Full of Days at The Compass in Provo, UT

After a child's fall from a haystack results in a broken rib and a child welfare case, an indigent ranching couple struggles to keep their family and livelihood intact. But there are chaotic forces in the valley—gods and devils, wilderness, and the west wind tunneling through.

Join us at The Compass August 6th at 6pm for a pre-release screening and conversation about the new film Full of Days.

Directed by Sarah Perkins and shot by Josh Sabey (the team behind The Book of Mormon Storybook), the film is inspired by their own family's child welfare case. It is the first filmic retelling of The Book of Job told from a female perspective. Watch the trailer here.

When: Wednesday, August 6th, 6pm

Where: The Compass Gallery, 250 W. Provo Center Street.

Wow, Fleur, this is fantastic. Thank you. That image of the group dancing to the piper's music is stunning and holy. May our presence leave such joy in its wake.

I walked the Camino de Santiago two years ago. Every word of this beautiful essay flooded my soul with memories of that beautiful experience. Those 5 weeks on the Camino was the closest to Zion I have ever experienced. I miss it every single day. I loved seeing the crosses everywhere, every day - crosses made of twigs woven into chain link fences, crosses etched into the primordial granite rock exposed through centuries of pilgrims' feet wearing down the path, crosses carved into trees, crosses made of hundreds of pebbles stretching a hundred feet down the middle of the trail, and most profoundly, crosses made by the outstretched arms of fellow pilgrims embracing me and extending to me everything I needed. I met Jesus every day on the Camino.