Mystery and Faith

A Personal Experience of the Supernatural

It was logical to be agnostic. There was no data, no proof to back up faith in the supernatural, the divine. I wanted to believe, but you can’t choose to believe, can you? I couldn’t.

Growing up, I’d been raised to believe in God (or should I say, “a God”?). The rudimentary conception was there was someone out there, a benevolent force who cared. They were concerned with how your life was going, but mostly let you steer. But if the show went way off script, things went haywire, they might pull the emergency brake for you, maybe? They were a friend you’d never met. You prayed to them, and searched for signs of a reply.

In my family, we didn’t discuss God. My mom didn’t make any supplications in front of us. Sunday mornings were for church; Monday evenings were for youth Bible study. Before supper, we prayed. Before sleep, my father came in and said prayers with me, encouraging me to add names of people who needed help.

After completing the Bible study program in eighth grade, I was confirmed. Sister Anna and I had a brief conversation in the church rectory. Facing one another, with feet flat on the floor, we sat in blue plastic chairs with thin silver legs. What we discussed, I don’t recall. Whatever I’d said, it was sufficient, I was pronounced confirmed.

Several years later, faith, or even the contemplation of the nonmaterial, disappeared from my life. Materialism made sense. Why should there be anything more than this physical universe? There was no data, no science, no experiments to convince me otherwise. No hotline to reach a mysterious God; no ladder to find heaven. My arms were too short to reach God, and legs too tired to make that leap of faith.

This line of thought rolled on for decades.

But then, a year ago, there was a series of inexplicable experiences that changed my mind. I’ve run the memories through my mind countless times, seeking a reasonable, scientific explanation for them.

It was my birthday; I was enjoying the sun in a park on the Lower East Side. An older Black man approached me and struck up a conversation. Perhaps due to my journalism background, I’m comfortable talking with strangers. He appeared homeless and nonthreatening. The conversation was light and polite.

Then it was time for me to move on. The man, who’d introduced himself as Kareem, said he was headed in the same direction. Several minutes later, we reached a point where our paths diverged. He turned to me and said, “I might try to come to tell you something sometime.”

Huh? I didn’t understand what this meant. “How would I know?” I asked.

“You’ll know by the sound of my voice,” he said.

I didn’t know what to think. But I was curious enough. I suggested we exchange numbers; we did. And we went separate ways. In the following weeks, he didn’t message me, nor I him. Kareem never asked for money, or any kind of help for that matter. So that was that.

Who knows why people say what they do? Perhaps he wanted attention or the feeling of human connection. While in college, I had spent a week volunteering at homeless shelters and soup kitchens. Part of that experience was doing an “urban plunge,” where for forty-eight hours I lived as a homeless person. The thing that struck me most was how quickly you become invisible. I couldn’t fault Kareem for being theatrical. It was a good strategy to stay sane.

Several weeks passed and I had the most powerful dream of my life thus far. A Black man appeared and stood several feet in front me. There was no backdrop in the dream, no scenery, and no sequence that led to it. Out of darkness and from nothing, there he was.

Whether he spoke, or I heard him with my mind, I’m not sure. But the message was clear, solid, and defined.

A single line: “God said you’ll always be OK.”

Instantly, I bolted upright from the dream, sobbing. In shock, I poured down the stairs into the kitchen and dropped to the floor, on my knees. My body was electric. The room was still and dark and quiet.

My roommate came downstairs, I’d woken her up. I told her my dream. We stood in silence.

It was almost 6 a.m., and I was too hyped up to sleep. So I went to the grocery store to get breakfast. I stood in the neon-lit aisle, feeling half-real, pondering whether I should get Cap’n Crunch, Honeycomb, or Corn Pops.

My phone pinged green, and there was a text from Kareem.

“How are you this morning?” he asked.

“I’m good, sir, how are you?”

“Remember you’re not just good. You’re great. Because God is great.”

Am I awake? What is awake? There is no thinking. I brought home three cereal boxes.

Later I told my mom this story. The story of the man coming up to me in the park on my birthday, and then telling me he is going to tell me something; and then having the dream, and then the text from Kareem, and if anyone could or should tell you the truth, it would be your mom, right?

My mom said that several years ago she took a meditation course. When the class was finished, the teacher gave each student a mantra word. My mom’s word? Kareem.

I’d never met anyone named “Kareem,” nor had my mom. The name comes from Arabic, and is translated as “generous,” as well as “dignified” and “dignity.” In the Quran, it is one of the attributes given to Allah (the Lord). As al-kareem, he is described as “The Most Generous One.”

In the Bible, the Book of Luke mentions the birthplace of John the Baptist, which scholars suggest was the town of Ein Karem (alternative spelling: Ain Karem).

The sequence of events doesn’t make sense. They seem connected, but how could that be? Some days I mull over these events and wave them all off. Other days I think it’s the most magical thing that’s ever happened to me, and I’m stunned to think I could be worthy of a reassuring word from God.

Several weeks later I was sitting at a coffee shop in Brooklyn. It was a gray day with intermittent rain that raced across the tall windows. The question kept nagging at me—had these events been sublime or merely sequential?

I wrote down the synchronicities I'd experienced. Was there a pattern, some unseen force behind the sequence, or was my mind drawing connections where there were none?

A few feet away, near the cash register, there was a young guy with short brunette hair and bright brown eyes. He was standing there, looking at me, and I looked up at him.

“God has a very special love for you,” he said.

My jaw went slack. I waved for him to come over and showed him my notebook. At the top of the page: “Ways God has spoken to me?”

This stranger and me, we threw our heads back and laughed. We high-fived. We were awestruck. When I interviewed him for this piece, he recalled that when he first saw me, “it was like there was a highlighter over you, saying how special you are to God.”

Walking to the train, I waltzed through the rain. There is no amount of money, no level of prestige, nothing that one could acquire or accumulate here on Earth that is better than this feeling—that an eternal, divine, benevolent God sees you and cares for you.

I felt profoundly content and wanted for nothing.

These experiences required me to revisit long-held assumptions about how the world works and the function of my existence in this world.

In mulling over these events, I kept coming back to mathematical probability. What is the probability of meeting a man named Kareem, who says he will “tell me something,” who then texts me in the early morning after a powerful dream? And then the probability for my mom to have a connection to this word? Or, in the following weeks, to be questioning this series of events, to have a stranger blurt out “God has a special love for you”?

These things seemed too coincidental to be mere coincidence, too interconnected to have arisen from pure chance.

Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, popularized the concept of “synchronicities.” Jung defined these as circumstances or events that appear meaningfully related yet lack a causal connection. An example often cited to illustrate this concept comes from a therapy session, which Jung wrote about in Synchronicity (1973). Jung’s patient was recounting a dream about a golden scarab. At this moment, a yellow beetle was buzzing outside, knocking itself on the window of their room. Jung opened the window and the beetle flew in. He noted that it was not the season for this insect, and this was atypical behavior.

According to Newtonian physics, the prevailing paradigm for the last three centuries, the physical world is governed by cause and effect. Like billiard balls on the green wool of a pool table, our visible world is discrete and sequential—the cue strikes the ball, which propels it forward, knocking into another, which carries on in its own trajectory. A causes B, and the linkage is clear.

According to Newtonian physics, it makes no sense for the recounting of a dream to result in changes in insect behavior. Or for the two to have any kind of relationship whatsoever. There is no physical linkage between the dream and the beetle; the dream did not summon the beetle. And yet somehow, in our minds—or at least in Jung’s mind—they have some kind of connection.

The closest physical science we have to synchronicity is quantum entanglement. In 2022, the Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to scientists who demonstrated this phenomenon. Their experiments showed that the physical world is not entirely explainable by Newtonian physics. At another level of measurement, a different model is required. In that realm, particles can affect each other instantaneously across enormous distances. This goes against the Newtonian model of cause and effect, and the restrictions of spacetime.

For me, a fantastical dream was haloed by people, statements and synchronicities that appear to underscore its veracity. This does not make sense. It is not logical.

My own life defies my ability to understand it, and there are scant options to verify or refute different interpretations. Yet, we learn from and are influenced by all of our experiences. My insistence on the rationality of materialism has given way to a considered acceptance that the individual can experience and observe supernatural events.

Marjorie Perry is a multimedia freelance journalist with bylines in The New York Times, The Economist, Slate and more.

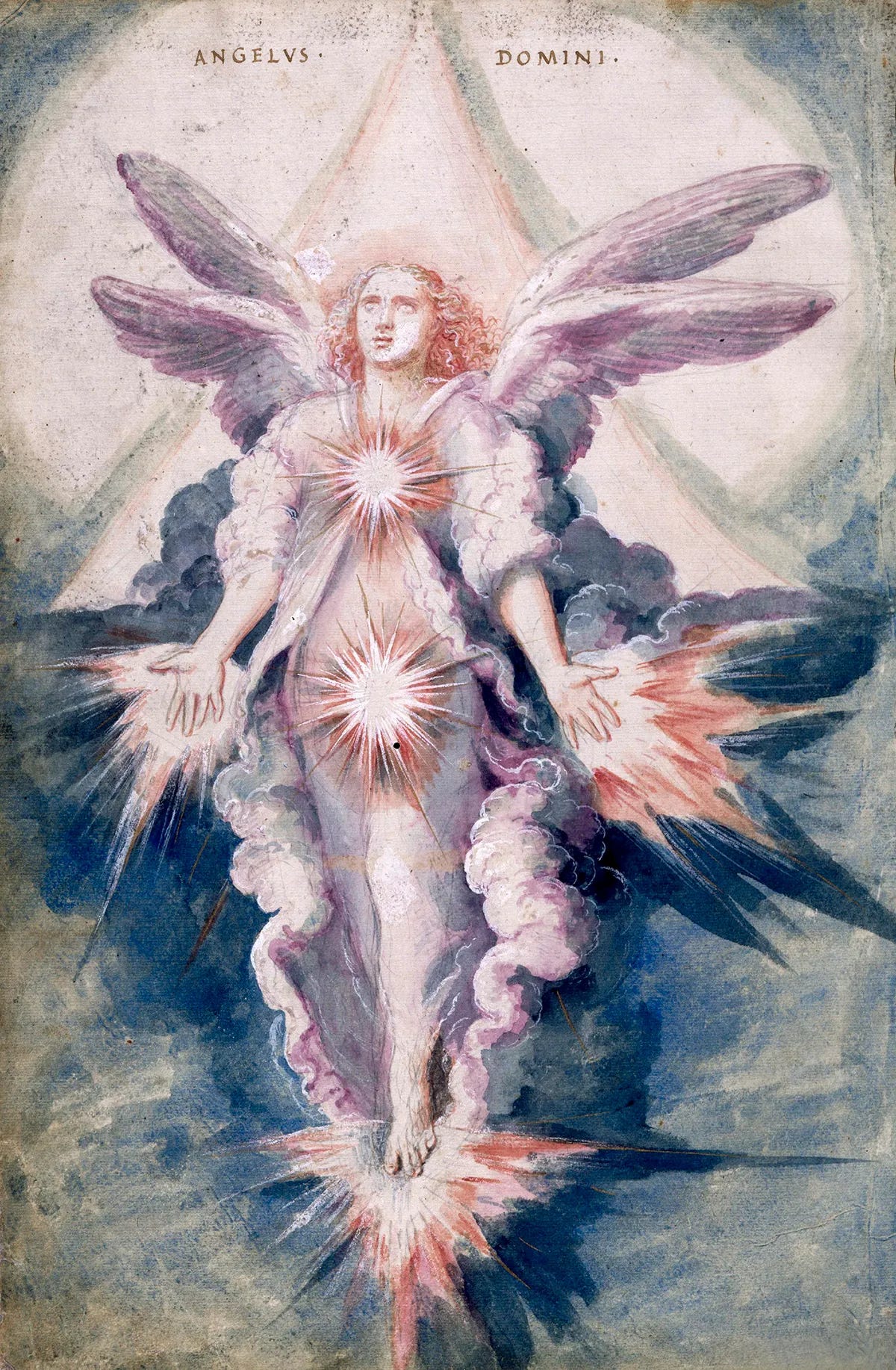

Art by Francisco de Holanda

Marjorie, I love this essay so much. Thank you for writing and sharing it. And your writing is wonderful. It gave me some of the feeling of elation you describe. The essay even showed up like a synchronicity with other things in my life. My favorite part is when you describe how you felt, and how nothing could surpass the sense of well-being. I resonated with so many pieces of the narrative, including being the person who seems to be sent some kind of divine message, being a messenger without knowing it, and having uncanny small things line up in a meaningful way.

I sent this to Rod Dreher the author of The Benedict Option whose new book Living in Wonder will be coming soon. He mentioned it in this SubStack.

https://open.substack.com/pub/roddreher/p/repeat-after-them-happy-warrior?r=c51da&utm_medium=ios

It seems to have evoked some interest.