A Heaven of Friends

Friendship as a Sealing Power

This is the first essay in our new column, Light Notes, written and curated by Megan Armknecht. The essays in this column are an invitation to slow down and explore the many ways we receive light in our lives, to allow our minds and hearts be illuminated together. To receive each new Light Notes essay in your inbox, click on the “manage subscription” link and turn on notifications for Light Notes.

When I was in the third grade, I started off the year with no school friends. I was used to it; it seemed a continuation of my second-grade year, after my family had moved from Las Vegas to Salt Lake City. I had struggled to find good friends in second grade, and I consigned myself to aimless recess wanderings in third grade, too.

A four-square invitation on a late August day changed my fate.

As I started out an afternoon recess, “wander[ing] lonely as a cloud,” someone called my name. I snapped out of my reverie and saw a classmate—a new one, someone who had only just moved to Salt Lake—wave me over. “Do you want to play four-square?” she asked. She was already playing with a group of kids from our class. All I would have to do was stand in line and wait to join once someone got “out.”

I agreed.

Four-square is one of those games you can play for ten minutes or the entire recess, depending on stamina and interest. The other kids we played with got bored after a few rounds, but this newfound friend and I stayed, played, and talked until the end of recess. And then we played and talked the next day, and the next, until we found best friends in each other.

I knew I had hungered for a friend, but I didn’t realize how much I needed her—and how, I think, she needed me—until we found each other.

Perhaps we feel the urgency of friendship most keenly in childhood. Certainly the childhood need for friends (and the various betrayals, triumphs, and tokens of friendship associated with childhood) reverberates throughout our lives. The contemporary cri de coeur “How do I make friends as an adult?” suggests a longing for erstwhile days when it was “easier” to make friends—whether in childhood or five years ago. We cannot go back to before, whether to the shared spaces of childhood, the intensity of summer camps, or early college days. The emotional, societal, and spiritual necessity of cultivating friendships is a challenge for the muddled, uncertain present.

I find it striking that Jesus referred to himself as our friend. It signifies friendship as a holy, divine love. “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends,” he said toward the end of his earthly ministry. “Ye are my friends, if ye do whatsoever I command you” (John 15:13–14, KJV). Christ’s invitation to friendship is an invitation to see ourselves as he sees us—as worthy of love. It is also, I think, an invitation for us to see Christ as he wants to be seen—as approachable and open.

Friendship binds our selves to others through attention, care, fun, and joy. This binding is not limited to linking ourselves and others; friendship connects us to places, communities, to our pasts, and to our futures.

Joseph Smith recognized the eternal significance of friendship. In July 1843, along the muggy banks of the Mississippi River, he declared that “friendship is one of the grand fundamental principles of Mormonism.”[1]

I love the audacity of this statement. It feels right in my bones and on my tongue. I want to believe it, but living it is a challenge in our contemporary world. Friendship is trivialized and commercialized in the twenty-first century. Friends are “added” by the click of the button, human relationships are reduced to algorithms, hypermobility disrupts emotional and physical intimacy, and individuality is prioritized over symbiotic social bonds.

Emotionally, I resist the desaturation of friendship. Friendship provides marrow to human flourishing, and cultivating the intimacy of friendship empowers us to look beyond our own needs and give the blessings of friendship to others. I want that “grand fundamental principle” to reorient me towards the deep soul work of forming friendships, despite the difficulties. Making, keeping, and sometimes, letting go of friends asks me to find beauty where I might not expect to find it, calls me to faithfulness, and, ultimately, invites me to see and love others as they are.[2]

Friendship delights in making the ordinary extraordinary. It asks us to expect the miraculous in unexpected places and people. I have frequently thought that one of the beauties of the restored gospel is the way the holy and the mundane are not mutually exclusive to each other. A farm boy sees God the Father and Jesus Christ. The voice of the Lord is heard in the seemingly unremarkable town of Fayette, Seneca County, New York (D&C 128:20). In a forsaken field in Missouri, a distressed mother can receive divine instructions on how to heal her injured son.[3] Even Joseph Smith’s description of friendship as “grand” and “fundamental” seems to pair these two adjectives—which can mean opposite things—as friends.

When I think about some of the most important friendships at various times in my life, the seemingly mundane beginnings of those friendships now gleam with significance. For example, that invitation to play four-square changed the trajectory of my elementary school years. I can still remember the heat of the blacktop of that late August day when my new friend invited me to play. In many ways, we were opposites: she the extrovert, I the introvert; she the adventurous, I the cautious; she the athlete, I the homebody. But there were miracles waiting to happen on that elementary school blacktop; our eager faith in the ordinariness of each other created a friendship that still blesses my life.

Friendship calls me to faithfulness. The word “faithfulness” can hold different meanings. While friendship can be viewed in terms of fidelity and loyalty, it can also mean being “filled with faith”—not knowing exactly if a friendship will last, or what directions friendship will take, and choosing to try anyway.

My husband’s job currently takes our family around the world. This comes with opportunities. This also comes with challenges. It’s hard being away from family and friends, especially when I want their support in the challenges and joys of my daily life. It’s not as though I can keep the friends I’ve made throughout the years in my pocket; I go in and out of their lives, they come in and out of mine, and we are grateful when chance and time bring us together again.

It takes faith to try making new friends, just as it takes faith and loyalty to keep up rituals of friendship with those far away from me. Friendship, like faith, cannot be forced. This means there will be unpredictability and risk. The riskiness of friendship means that there have been (and will be) periods of loneliness. It means that I have (and will) hurt others, and they will (and have) hurt me, whether through miscommunication, unmet expectations, or thoughtlessness. Faithfulness does not shield us from hurt. But it does give us courage to try again, or, perhaps, to let go—believing that men and women are “that they might have joy” throughout our various seasons of life (2 Nephi 2:25).

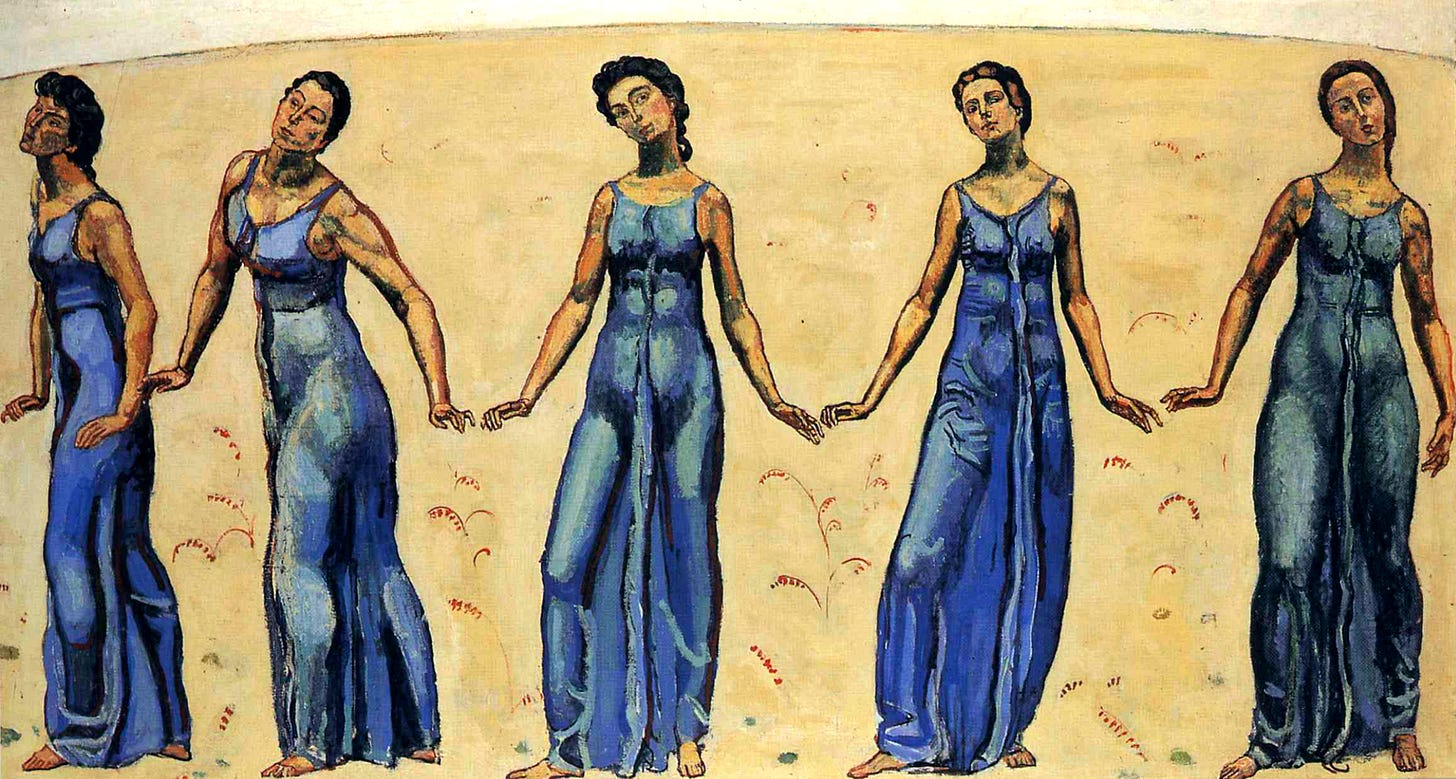

Even though friendships ebb and flow over the course of mortality, friendship is a surprisingly resilient bond of love. Binding human relationships through love is a central project of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. It is the driving impulse behind sealing ordinances and in our ideas of heaven. We often talk about this in terms of familial love. But friendship’s love is sacred, too, and can bind us to each other in ways that span our lifetimes (and, I believe, our eternities). In Doctrine and Covenants 128, Joseph Smith wrote of the need for a “welding link of some kind or other between the fathers and the children” (D&C 128:18). He also used the image of welding to describe the bonds of friendship. Friendship, he said, was like links welded together in a blacksmith shop: “Iron to iron; [friendship] unites the human family with its happy influence.”[4] As friends, we come together as equals, as iron and iron, made of the same elements of divinity, mud, salt, and hope, as we strengthen each other and whatever communities we find ourselves within.

My life is richer because of good friends. Friendship is a relationship that asks for renewal, but which also renews. And even if time, distance, and circumstances weaken bonds, I still believe there is something that lasts, something that leaves its residue on my soul, something pulling at a subatomic level to remind me of the times I have purely given and received love from members of God’s family whom I have, at various times of my life, called the blessed name of friend. And not only to remind me, but to find ways to bring heaven now, wanting all of us linked together.

I want them all with me, in front of me. I want us in the verdant green days of Cambridge, bathed in fairy lights; in confidences shared under the soaring maple tree of the elementary school play yard; in intense conversations about God while crammed five-people deep in a Honda Civic; in laughter echoing in the pockmarked kitchen of a five-story Ukrainian krushchyovka; in late-night walks under the Narnia-like street lamps of a medieval university town; in hurried realizations on the paved sidewalks of Provo, Utah. I want them all in front of me, with those thrills of recognizing, Yes. Eureka. I have found joy. I have found camaraderie. We have found each other. I see you, love you, even if that love changes over time, even if you one day do not love me anymore. Iron welded to iron, our past has linked us, and our present and future will never look the same.

[1] History of the Church, 5:517; from a discourse given by Joseph Smith on July 23, 1843, in Nauvoo, Illinois; reported by Willard Richards.

[2] See Iris Murdoch, The Sovereignty of Good, 2nd ed. (Routledge, 2009), 66.

[3] See Alexander L. Baugh, “‘I’ll Never Forsake’: Amanda Barnes Smith (1809–1886),” in Women of Faith in the Latter Days: Volume One, 1775–1820, Richard E. Turley Jr. and Brittany A. Chapman, eds., (Deseret Book, 2011), 327–42.

[4] History of the Church, 5:517; from a discourse given by Joseph Smith on July 23, 1843, in Nauvoo, Illinois; reported by Willard Richards.

Megan Armknecht is an associate editor for Wayfare. She is a writer and historian currently based out of Bangkok, where she lives with her husband and two children.

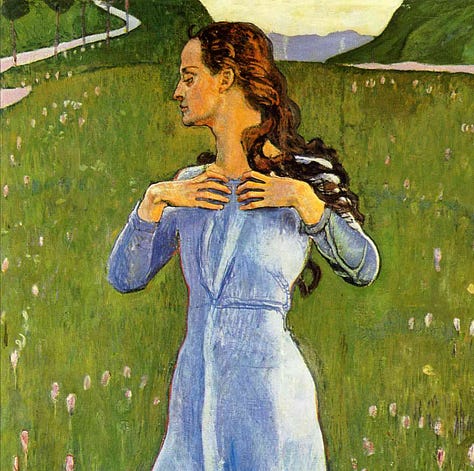

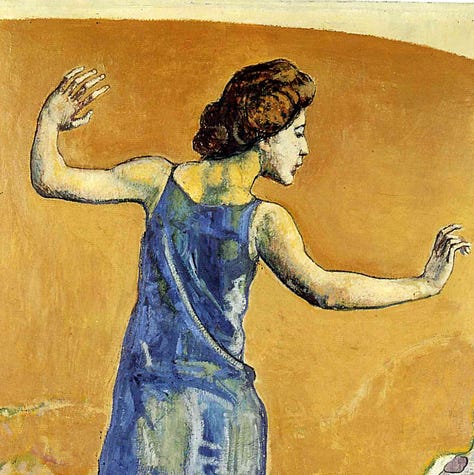

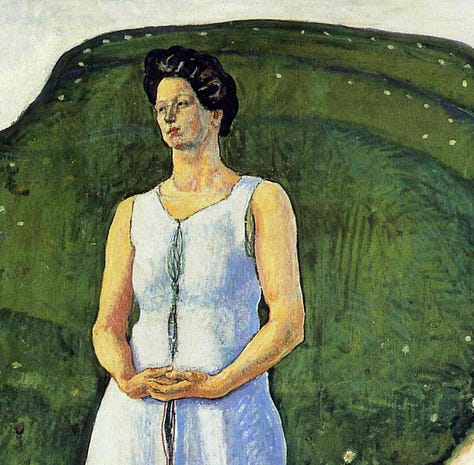

Art by Ferdinand Hodler.

KEEP READING

VALENTINE’S DAY COLLECTION

Find the whole collection here.

PRESIDENTS’ DAY COLLECTION

Find the whole collection here.

ORATORY SERIES

Find the whole series here.

POETRY

To subscribe to the Poetry section, click on “manage subscription” and turn on notifications for Wayfare Poetry.

THEOLOGY

To subscribe to the Theology section, click on “manage subscription” and turn on notifications for Wayfare Theology.

love love love this, megan! this whole piece reminds me of one of my favorite, and for me theologically resonant, moments of the Lord of the Rings films, where Aragorn has been crowned king and the hobbits bow along with everyone else, until he comes over to them and says, "My friends, you bow to no one."

Makes me cry every time; that's what i imagine whenever i read jesus referring to the disciples, or us as readers, as his friends.

anyway--thank you for this, friend.

Beautiful, Megan. So grateful to count you as a friend. 💕