The Art of Healthy Conflict

Several years ago a friend confided that she was completely disengaging from political discourse. She decided to not only stop reading the news but to stop talking about politics in any setting. She hated how toxic politics had become, and she disliked the discomfort of disagreeing with people she liked. Although hers is a common story, her solution—staying away from politics entirely—isn’t ideal.

One of the tragedies of America’s current politics is a vicious cycle where contemptuous and hateful discourse scares away many who are thoughtful, curious, and open-minded and leaves the battlefield of ideas to those who are most angry and opinionated. It’s worth contemplating how our politics might be different if town council meetings, school board meetings, state legislative hearings, and the inboxes of elected officials at every level were filled with peacemakers on all sides who debated their views with humility and respect. How might the ranks of legislative bodies look if more peacemakers showed up to town halls, caucus meetings, and meet-the-candidate events to ask candidates not only about their views on immigration, taxes, or healthcare policy but about their willingness to disagree with dignity? Surely we need more, not fewer, peacemakers choosing to participate in politics.

As someone who works in public policy, I’ve been grateful for the clear guidance from my faith leaders on how to participate in politics without becoming bitter or hateful. As affective polarization, divisive rhetoric, and political violence in the United States have increased over the past ten years, leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have spoken with increasing frequency and urgency on the importance of unity and the responsibility of Christians to serve as peacemakers, not just in a faith setting but in the emotionally charged political arena.

A few examples among many are helpful. In his April 2023 sermon, “Peacemakers Needed,” President Russel M. Nelson taught, “As disciples of Jesus Christ, we are to be examples of how to interact with others—especially when we have differences of opinion.”

For decades, President Dallin H. Oaks has spoken powerfully and repeatedly on peacemaking in politics.

In a 2014 address President Oaks gave this counsel:

On the subject of public discourse, we should all follow the gospel teachings to love our neighbor and avoid contention. Followers of Christ should be examples of civility. We should love all people, be good listeners, and show concern for their sincere beliefs. Though we may disagree, we should not be disagreeable. Our stands and communications on controversial topics should not be contentious.

In 2020, President Oaks repeated the message:

In a democratic government we will always have differences over proposed candidates and policies. However, as followers of Christ we must forgo the anger and hatred with which political choices are debated or denounced in many settings. . . . Anger is the way to division and enmity. We move toward loving our adversaries when we avoid anger and hostility toward those with whom we disagree. It also helps if we are even willing to learn from them.

And again in 2024 President Oaks said:

We need to love and do good to all. We need to avoid contention and be peacemakers in all our communications. This does not mean to compromise our principles and priorities but to cease harshly attacking others for theirs. . . . As we pursue our preferred policies in public actions, let us qualify for [Jesus Christ’s] blessings by using the language and methods of peacemakers.

Dozens of other Church leaders have amplified these messages.

Knowing that we should be peacemakers is easier than actually doing it. We can get it wrong by thinking an issue we care about is so important we’re justified in treating an opponent poorly. We can also, like my friend, get it wrong by mistakenly equating peacemaking with the avoidance of conflict. It’s true that peacemaking is inconsistent with contention, but there’s a difference between contention and conflict, and peacemaking is entirely consistent with the right kind of conflict.

In her brilliant book High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out, Amanda Ripley writes, “Good conflict is vital. Life would be much worse without it. It’s a lot like fire. We need some heat to survive—to illuminate what we've gotten wrong and protect ourselves from predators. We need turbulent city council meetings, strained date-night dinners, protests and strikes, clashes in boardrooms and guidance counselor offices.”

Healthy conflict is also the engine of a well-functioning democracy. In his recent book American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation―and Could Again, Constitutional scholar Yuval Levin clarifies that in America’s system of government, unity does not mean agreement. Rather, unity is “acting together even when we don’t think alike.” It’s a pithy summary of Madisonian pluralism, but it’s also an important insight: The most effective peacemakers enter the fray, embrace healthy conflict, and help channel it towards productive ends.

Levin also dispels another misunderstanding of peacemaking, that the sort of idealism necessary for peacemaking is really just for suckers, that to accomplish anything consequential in politics one must be purely Machiavellian. In a recent speech at Brigham Young University, Levin argued that “cynicism is naive. It’s never really quite right. It doesn’t actually explain why people do what they do. The fact is that people want to be idealistic, want to be part of something bigger than themselves, to contribute to something that they can respect and can be proud of.”

Peacemakers should be encouraged by a growing body of social science on the phenomenon of affective polarization and on the interventions that work to reduce it. There’s an expanding movement of organizations teaching us the art of healthy conflict.1 And there is a burgeoning genre of new books with practical guidance for peacemakers.2

So what does healthy conflict look like in practice? Amanda Ripley tells the story of a 2018 exchange program between members of a liberal Manhattan synagogue and a group of very conservative Christian corrections officers from Michigan. The New Yorkers spent several days living with the Michiganders, learning to handle a gun, visiting the prison museum, and talking about divisive political topics. Two months later the roles were reversed, with the New Yorkers hosting their new friends from Michigan, together attending their Upper West Side synagogue and walking in Central Park while continuing to argue about immigration, gay marriage, and more.

The exchange had three rules: (1) Take seriously the things people hold dear; (2) Don’t try to convince someone they’re wrong; and (3) Be curious. If a participant said something shocking and another person didn’t know what to say, they were encouraged to respond, “Tell me more.”

The participants acknowledged that while they didn’t radically change their views on particular issues, the experience transformed their perceptions of the other side, and they became friends who have continued corresponding. One progressive participant described the lasting effect of the experience: “The main impact this had on me was that I couldn’t tolerate the generalizations that were being posted on social media about those conservatives. I wasn’t willing to hear that from my friends and I wasn’t willing to read it on social media because I realized life is much more complicated and that kind of language is really not helpful to anybody.”

The power of healthy conflict to change perceptions is important. Research by More in Common has shown that both the right and the left overestimate the extremism of the other side by about 25 percent, creating a “perception gap” that causes us to wrongly view every election as existential and to sink into despair at the prospect of our side losing. At worst those misperceptions prompt us to preemptively violate norms in the belief that the other side is going to do something terrible so we’re justified in taking radical actions to stop them. Peacemakers (including through the groups mentioned above) can help both sides to understand what the other side actually believes, a powerful antidote to hatred and polarization.

As in other settings, even a single peacemaker can change the tone of a group conversation, either in person or online. I love it when this happens in movies, but it also happens in real life. In the fall of 2016, just a few weeks before the election, a friend posed a question on his Facebook page: “What is the best good faith argument in favor of the presidential candidate you oppose?” For a few hours the hostility, at least on his thread, was replaced by empathy, curiosity, and strikingly eloquent descriptions of what the responders’ opponents would have described as their views.

How we think of ourselves also matters. To be effective peacemakers doesn’t mean we must collectively moderate our positions or pretend we don’t disagree, but it’s wise to subordinate our political identity to our many other identities. Whether we are a conservative, libertarian, moderate, or progressive, we can make that identity less important than our identity as children of God, parents, friends, neighbors, and sports fans. Putting politics in their proper place allows us to create a connection with people whose politics may be completely different but who share a more important identity with us.

None of this is to say peacemakers should jump into every debate, put themselves in dangerous situations, or engage with those acting in bad faith. David French, a former litigator, says he considers whether someone with whom he disagrees is acting like opposing counsel, paid to disagree with him at all costs, or the jury, perhaps persuadable if he is respectful and persuasive.

And of course persuasion matters. As a practical matter, entering the political fray as peacemakers is not only better for our souls but it is more persuasive. We can all name the great historical examples of peacemakers who brought about policy ends, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela, but we can also probably each recall personal examples of the success of healthy conflict. Two years ago I volunteered as a judge in my daughter’s speech and debate tournament. I was consistently impressed that the best debaters were those who marshalled good arguments and who acknowledged good faith on the part of the other side. They were the ones who avoided statements like “my opponent is completely wrong” in favor of “my opponent makes a good point, but . . . “ or “my opponent is correct about X, but is leaving out the importance of Y.”

Even done correctly, healthy conflict isn’t fun. It’s uncomfortable and hard. It can involve pointed criticisms, forceful arguments, and skepticism. Politics isn’t clinical and detached; it’s personal, and it’s human nature to take it personally when someone says we’re wrong.

To be most effective, healthy conflict must also include the tools of peacemaking: curiosity, humility, and an assumption of good faith by one’s opponents. We should also have realistic expectations. Healthy conflict in a political setting doesn’t always result in tangible progress, and there will often still be winners and losers. That’s the nature of a democracy. But active peacemakers can create the conditions most likely to produce progress. And they can do so in a way that allows each side to maintain a relationship and some degree of goodwill towards the other side. As one person described it, the right kind of conflict allows us to express our view and then “tolerate the discomfort of someone else’s opinion.”

I hope my friend will decide to step back into politics. The world, and certainly American democracy, needs far more people who have not only conviction about policy topics but about practicing Christian love, mercy, and forbearance in the public square, especially towards political opponents and even when those opponents don’t reciprocate. Our mortal calling isn’t to be an activist for a political cause but to become like Jesus Christ. As with life itself, none of us will be perfect. Many of us have been part of the problem at times, and becoming successful peacemakers requires that we offer patience and grace to others and ourselves as we try to soften how we talk and what we do.

We have the prophetic guidance and the tools to participate in politics as peacemakers, not shying away from political conversations and causes but rather joining them with respect, curiosity, and humility towards our opponents. Someday most of the causes that feel so important in the moment will be moot, but we can act now in a way that makes us better disciples of Jesus Christ and sets the standard for Christian peacemaking.

Gordon Larsen is the senior advisor for federal affairs to Utah Governor Spencer Cox.

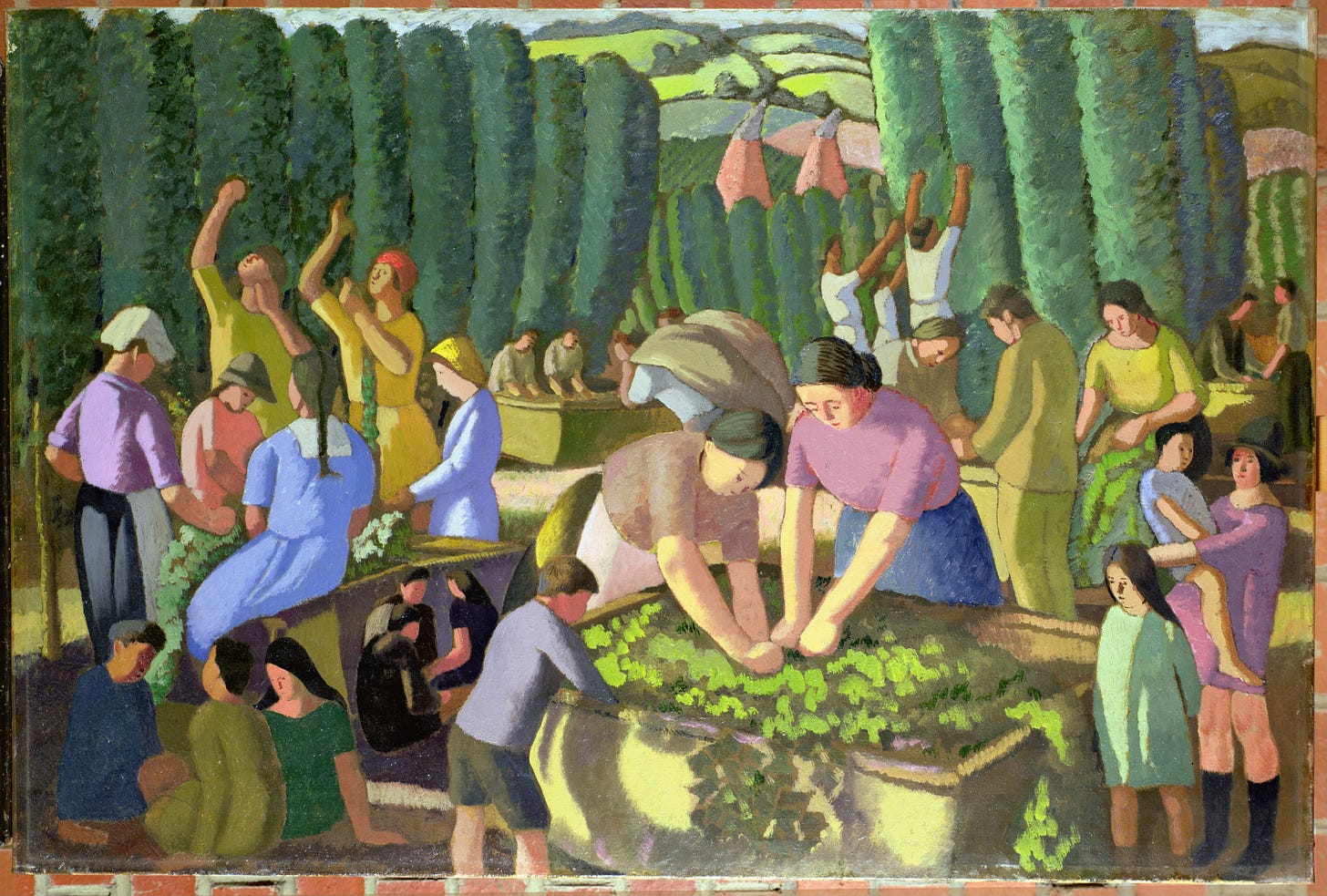

Art by Thomas Saunders Nash.

See organizations such as Braver Angels, the Constructive Dialogue Institute, the One America Movement, the American Exchange Project, StoryCorps, and The Dignity Index.

See Ian Leslie, Conflicted: How Productive Disagreements Lead to Better Outcomes; Yuval Levin, A Time to Build; Adam Grant, Think Again; David Blankenhorn, In Search of Braver Angels; Amanda Ripley, High Conflict; Peter Coleman, The Way Out; Lilliana Mason, Uncivil Agreement; Monica Guzman, I Never Thought of It That Way; Ben Sasse, Them; David French, Divided We Fall; John Inazu, Confident Pluralism and Learning to Disagree; Alexandra Hudson, The Soul of Civility.