“I Have Called Thee by Name”

Reflections from a Prison Educator

Names hold importance. They distinguish you as an individual. They link you to previous generations, especially when someone is named after an ancestor. Biblically, name changes signified a major shift in one’s identity or relationship with God. They are used to refer to God (Father, Elohim, Mother) and Christ (Wonderful, Counselor, Emmanuel). To be named is to be known.

However, for my students in the Utah State Correctional Facility, that part of their identity was taken away. They were identified only by a number.

As a volunteer teaching assistant with the University of Utah Prison Education Project, a program that offers university-level courses to incarcerated individuals for credit, I quickly learned that human dignity is rare inside the walls of a prison. In addition, being a twenty-two-year-old woman in a men’s maximum-security prison meant that within the first ten minutes of my first day, I had already been stared at and yelled at by inmates before arriving in the education wing. There was an atmosphere of violence everywhere. It was suffocating, and the institution’s location in the middle of the Utah prairie near Tooele made it feel deliberately secluded. I came to the conclusion that I had clearly made a mistake. Why would I voluntarily come to this place?

However, my feelings changed as my students entered the classroom. One by one in their white prison uniforms, they thanked me and shook my hand. Some hands were old, some young, some covered in tattoos. But each hand expressed gratitude. I quickly realized what this course meant to these men—it was an opportunity for a few hours a week to be treated as human beings with the capacity to progress, to be more than the crimes that had landed them in prison. Locked away from family and the world, our presence indicated that they were not forgotten; they were individuals. They were known.

Each week at the start of class, we passed around an attendance sheet for students to write their names on. The materials we could bring into prison were very limited, so a scrap piece of paper and a pencil would usually do. I noticed on the sheet that the students wrote their name and their inmate numbers. After a few weeks of this pattern, I told the students that we only required their names on the form and that the number was unnecessary. This instruction in any other context would have had minimal impact, but for these men, losing the number represented freedom from their past, their darkest moments. How would you like to be defined by the worst thing you have ever done? In our classroom, they were not assigned a number; they would always be called by name.

Ironically, the course we taught was on the history of slavery in the Atlantic and the United States. Throughout the semester, students made connections between how dehumanization tactics used in chattel slavery were similar to what went on inside the prison walls. The accounts from former enslaved people that they read about in the textbooks were all too real at times.

Although we didn’t discuss it in class, I had cause to reflect on the first person to be visited by an angel in the Old Testament, the enslaved1 woman of Abraham and Sarah, named Hagar. When Sarah is found barren, she gives her servant Hagar to Abraham, so that she may provide him with a son. When she discovers the plan has succeeded and that Hagar is pregnant, she “deals harshly” with Hagar, causing her to flee to the wilderness (Genesis 16:6, NRSV). An angel finds her in the wilderness by a fountain and assures her, “The Lord hath heard thy affliction” (Genesis 16:11, KJV). At this moment, she calls God by a different name, not the traditional one commonly found in the Old Testament. She calls him Elroi. Elroi in Hebrew means “the god who sees me.” The same God who saw Abraham and promised him that he would be the father of a great nation saw Hagar, Abraham’s slave woman, and made her the same promise.

In the United States Constitution, the Thirteenth Amendment states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.” Hagar and my students were in different circumstances. Her enslavement was based on her ethnicity, and my students were serving criminal sentences as punishment for their use of their agency. But the common denominator of dehumanization was nonetheless the same. Those who are imprisoned often have jobs, but they are unpaid and not protected by the same labor laws as those outside. I learned of the barbaric working conditions from my student Brad, who was a painter in the prison and suffered from lung damage, causing him to miss class because the prison refused to give them masks. If Elroi saw Hagar in her affliction, he saw Brad too.

Amidst the triumphs of the course, with students receiving high grades they never thought possible, there were moments of deep sorrow. Arriving in class one day, I saw one of my brightest students, whom I will call Greg, sitting at his desk. His eyes were bruised purple, his head stapled shut, and he had red, strangled marks around his neck. It was a horrific sight. We had heard earlier that week that the prison had been locked down, but we didn’t know it was because Greg had been jumped. A gang had tried to kill him. He was lucky, he said; it was not uncommon for these gangs to succeed in other circumstances. He nonchalantly explained how he was rushed to the hospital in an ambulance. But instead of discussing the situation further, he wanted to hear about my upcoming trip to Europe. I held back my tears until I left. (A general rule we were told in training is not to cry in prison.) Some would say he was getting what he deserved for having committed a crime. Although I never knew what crimes my students committed, serious crimes are not uncommon. Time and time again, I was met with the question: Does such violence and dehumanization really meet the demands of justice?

Tolstoy would say no. Inspired by figures like William Lloyd Garrison and Adin Bolou, he argues in his book, The Kingdom of God Is Within You, that violence cannot be resolved with violence. The only solution, he asserts, is rooting yourself in Christ’s unconditional love. Quoting William Lloyd Garrison’s 1838 “Declaration of Sentiments Adopted by the Peace Convention,” Tolstoy writes,

The history of mankind is crowded with evidences proving that physical coercion is not adapted to moral regeneration; that the sinful dispositions of men can be subdued only by love; that evil can be exterminated from the earth only by good.

In short, we overcome through love and goodness.

The kingdom of God within, as I see it, is the divinity within us all, an intrinsic part of our spiritual DNA as divinely created beings.

The kingdom of God was certainly within my students. I saw it through their kindness to me as they expressed how proud they were when I got into Harvard. The kindness they showed to one another when they would take notes for a classmate who missed a lesson or share a pencil, since they might only receive two for the entire semester.

But what could be done if the system that incarcerated them would not recognize such moments of humanity, love, and kindness, viewing them merely as a number and a crime? As static, fallen beings? A system that would not even call them by their names—the same names that their mothers chose, that their friends and teachers called them by, the names that their grandmothers wrote in cursive on a Christmas present tag. One cannot forget that there were moments before that one horrible moment, the action, the catalyst that led to their imprisonment.

Teaching in prison was not like a movie with an epic ending. Unlike The Dead Poets Society, no one stood on a desk on the last day and said, “O Captain, My Captain.” The last day ended quietly, as the first had begun, with handshakes and a thank-yous from my students, some wishing me luck in my graduate program. Unlike in usual university courses, where students promise to keep in touch or assume they might run into the instructor on campus, I knew that when I walked out the prison doors, I would never see or hear from my students again due to prison regulations. The end of the course felt final, but I felt completely unresolved. I was left with questions, as a proud teacher would be when they saw their students succeed and excel with no real fanfare or reward. Who would realize that my students were trying to change, trying to become more than their pasts? Who would care that they were beaten and assaulted? Who could do something? Who would know their hearts?

There was no answer to the question of who would know or who would care. But I came to the conclusion, the belief, that there was one person who cared about every effort my students made to become more than who they were and who knew of their suffering. Isaiah famously described that person.

He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted.

But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed. (Isaiah 53:3–5)

He knew. He had to. He was acquainted with the sorrow and sins of the men I taught, laughed, and mourned with, as well as my own. When he said in Matthew 25:36 that he was in prison, he was. For any peace or justice, I had to entertain the possibility of the literalness of the Atonement, with all of its metaphysical possibilities in the past, present, and future.

“O Israel, Fear not: for I have redeemed thee, I have called thee by thy name; thou art mine” (Isaiah 43:1).

Through the prison walls, the noise, the blood, the shame, the horror. He will call to them, “I have redeemed thee.” He will call them by name.

Grace Chipman is a student at Harvard Divinity School and a recent graduate from Brigham Young University in History and Global Women’s Studies from Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Her interests include religious women’s history, theology, and teaching.

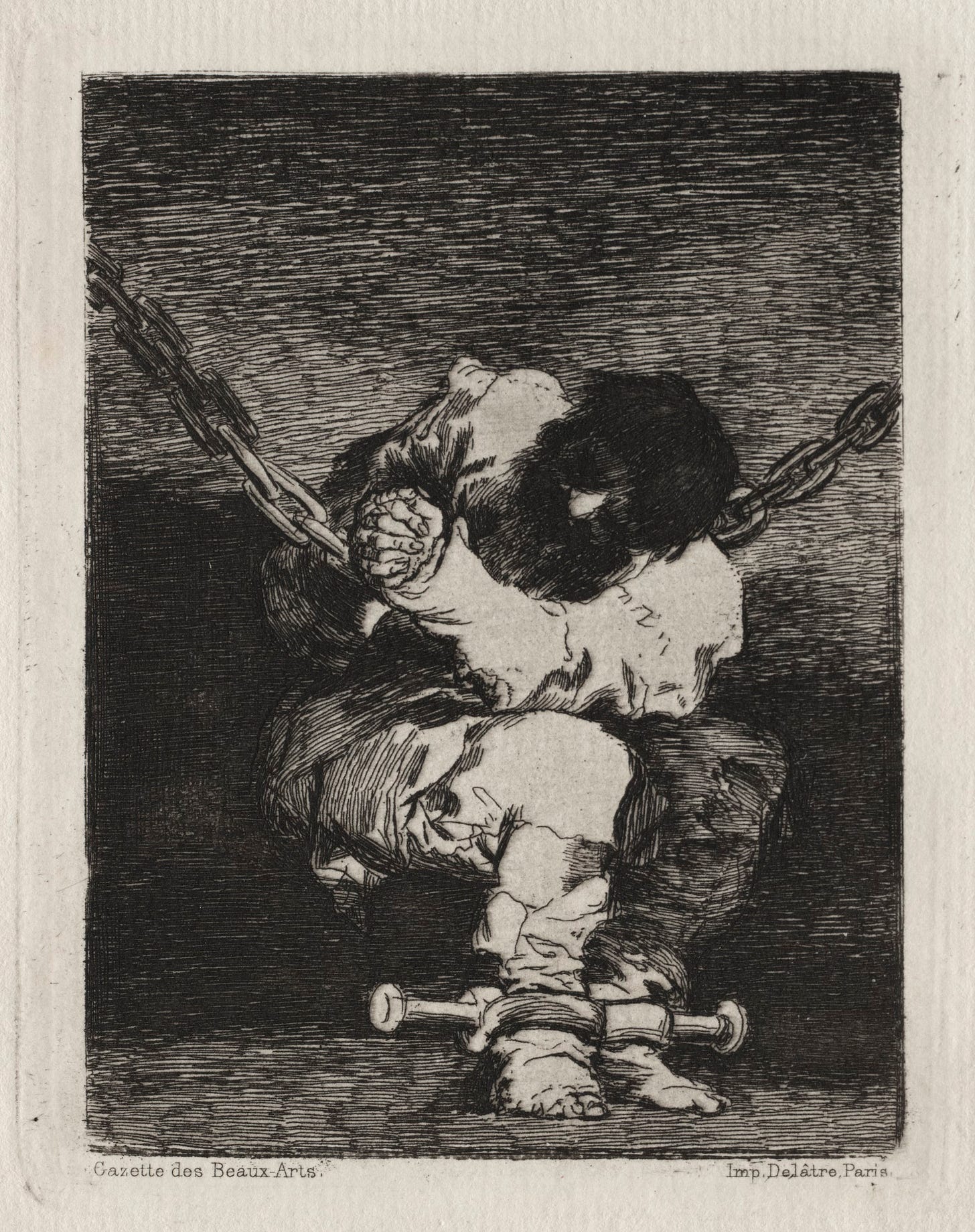

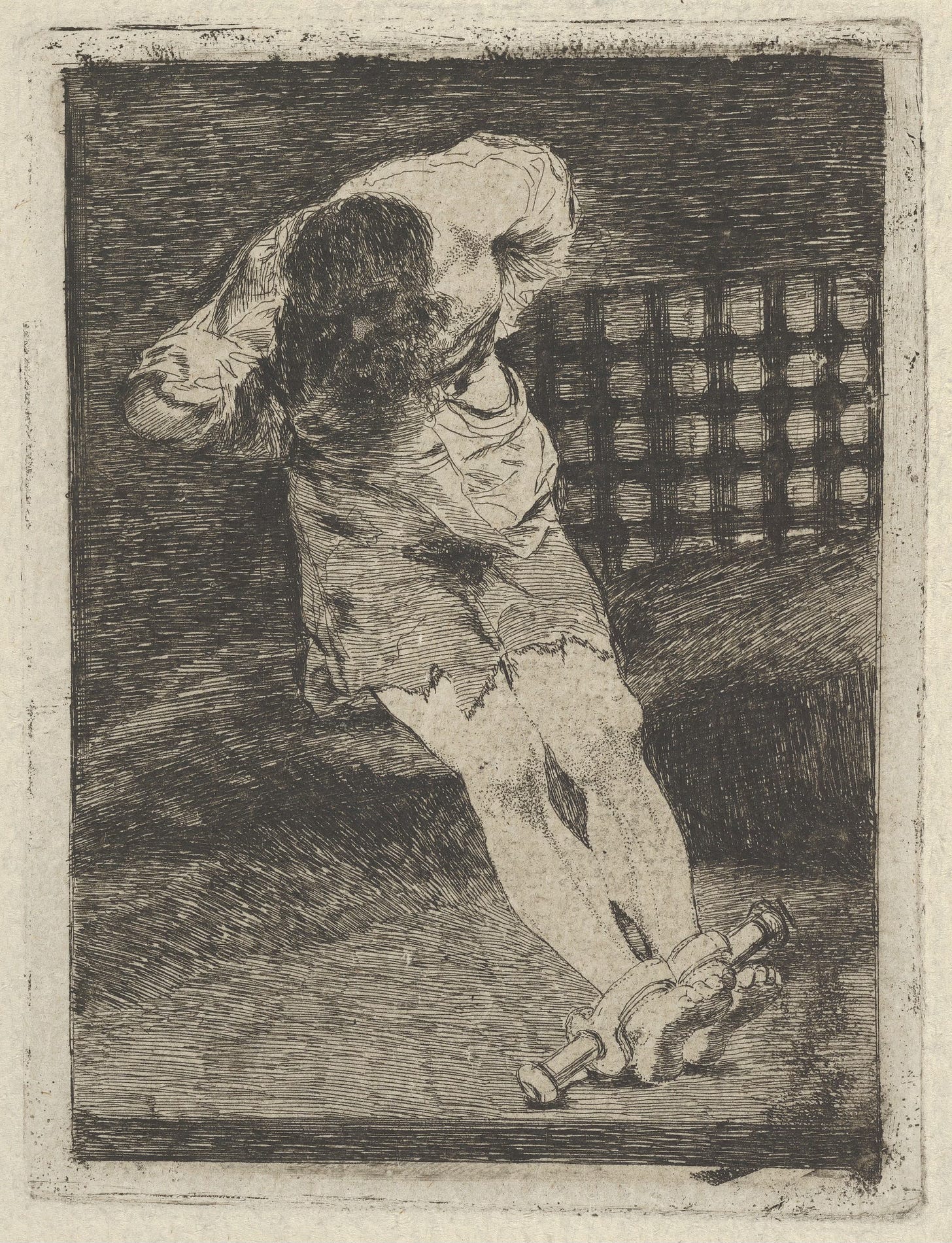

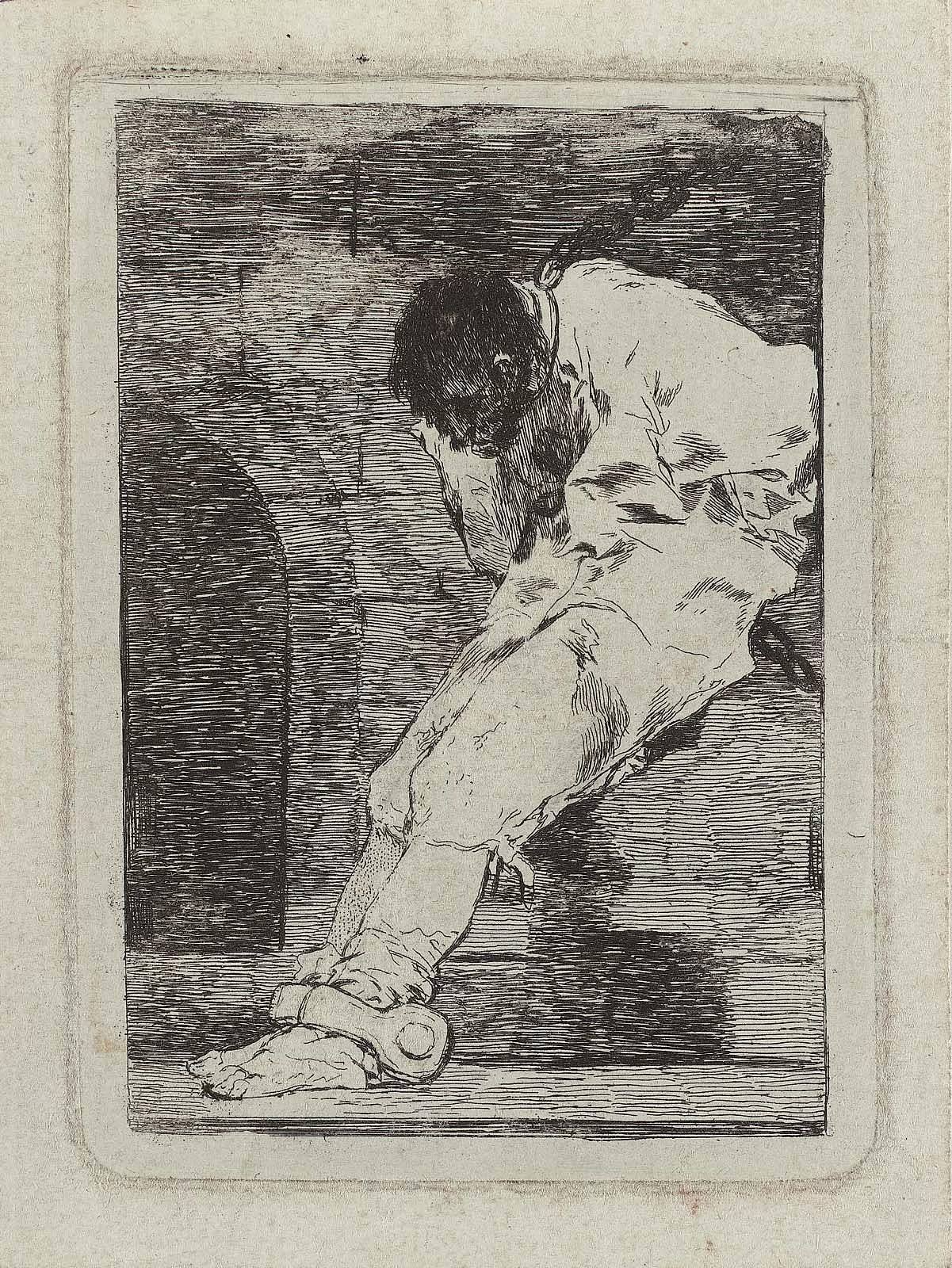

Art by Francisco de Goya (1746–1828).

Although the Bible uses the term “handmaiden,” this piece aligns with common womanist theology understandings that the handmaiden refers to an enslaved woman.

Profound experience, beautifully written!