Let Us Bow Our Heads and Play

An Excerpt

This essay is an excerpt from a longer treatment of the subject found here. Please enjoy!

I find it amusing that the most chipper hymn in Latter-day Saint hymnody is a paean to putting your nose to the grindstone: “We all have work; let no one shirk. Put your shoulder to the wheel!”

Latter-day Saints often use the language of labor to describe God’s activities and our own discipleship and worship. In Moses 1:39, we read that it is God’s “work and . . . glory—to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.” We are advised to “work out [our] own salvation with fear and trembling” (Philip. 2:12). We call our liturgical participation in the temple “temple work.”

But while we acknowledge the central importance of “work” in LDS discourse, we might nevertheless consider whether the language of work might have unintended side effects. Does all “work” and no play make Peter Priesthood a dull boy?

For some, an overreliance on the rhetoric of “work” can have the effect of making consecration feel like hustle culture, like punching your time card for your corporate gig, like something you only do begrudgingly in exchange for compensation. Discipleship, however, is not hustle culture, and God is not a productivity guru. In fact, Jesus goes to considerable effort in the Parable of the Laborers in the Vineyard to make clear that the Kingdom of Heaven does not work like the job market. But when we rely too much on the language of “work” we run the risk of importing the logic of market capitalism into our theology, which can lead to the commodification of spirituality or the heresy of the prosperity gospel.

In a work-focused spiritual framework, anxieties like scrupulosity can easily take root. The focus on effort can become so all-consuming that it overshadows the joy and spontaneity that should also be part of discipleship.

It therefore seems wise to develop a parallel LDS discourse of “play,” as a complement and counterbalance to the central and well-developed discourse of “work.” To do this, we’ll take a closer look at ideas from Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (1938) and Hugo Rahner’s Man at Play (1963). Together, these thinkers help reveal how playfulness might offer us new spiritual insights.

Deus Ludens: God’s Playfulness

Reading Jesuit priest Hugo Rahner as a Latter-day Saint is a stimulating experience, even if some of his ideas do not align frictionlessly with our theology. Rahner, in his book Man at Play, describes God as “Deus ludens [God the Player], who, one might say, as part of a gigantic game called the world of atoms and spirits into being.” Rahner argues that God’s creative act can be appropriately called “play” because Creation was not performed out of necessity, constraint or compulsion, but out of a “joyful spontaneity.” In a word, God created the world because it was—if you will—fun.

In fact, as Rahner describes, many creation myths evoke this notion of a playful, childlike genesis. “Everywhere we find in such myths an intuitive feeling that the world was not created under some kind of constraint, that it did not unfold itself out of the divine in obedience to some inexorable cosmic law; rather, it was felt, it was born of a wise liberty, of the joyous spontaneity of God’s mind; in a word, it came from the hand of a child.”

Latter-day Saints don’t accept all implications of a playful God. According to Rahner, it is not only Creation, but also the Incarnation which might be called play. In the Incarnation, Christ comes in costume; God “plays dress up” and dons a mud mask to go amongst his creatures in disguise. For Latter-day Saints, the embodiment of the Incarnation is not a temporary disguise for God but an essential aspect of his exalted reality. Nor do we believe that we have been created merely for play. If Rahner suggests that we mortals were created only as divine “playthings,” we Latter-day Saints must disagree. In our view, created though we are by the Divine Child, we will someday be exalted as children and heirs. We are participants in the game, not dolls.

These are not insignificant theological differences. Even still, Rahner’s thinking about the playfulness of God is attractive to me, and I believe his conclusion—that God is a playful Being—even if I do not assent to some of the theological reasons he advances to reach that conclusion.

We may grant that the Creation of the Earth was deliberately planned and necessary, but can we not concede that there is a certain gratuitousness about Creation? There seems to be something superfluous about the beauty and grandeur of the earth, its flora, fauna, and topography. There doesn’t seem to me to be any strict necessity for Gerard Manley Hopkins’ brinded cows, stippled trout, or fire-catching kingfishers.

Even apparently horrible and hideous creatures have a certain whimsical charm: the spider with its too-long legs is like a stilt-walker on parade; the bulging bullfrog with its full elastic cheeks is like a rubber ball; the snake like a child’s jump rope. Nature may be, as Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote, “red in tooth and claw,” but it is also comic—like a child who has amateurishly applied her mother’s red nail polish and lipstick.

One might accept Darwinian natural selection as the most plausible account of how the earth and its strange species originated, and still conclude that play is built into the very fabric of life. At least, that was the realization I came to when I read David Toomey’s new book, Kingdom of Play: What Ball-bouncing Octopuses, Belly-flopping Monkeys, and Mud-sliding Elephants Reveal about Life Itself (2024).

Toomey’s surprising argument is that the characteristics of play are the characteristics of natural selection itself. Like play, natural selection is purposeless (it does not have an intention or objective towards which it is striving), provisional (it responds to whatever conditions or context it finds itself in), and open-ended (the evolution of any organism has no moment of arrival and no endpoint). As Toomey puts it: “Since life is best defined as that which evolves by natural selection, and since natural selection shares a great many features with play, we require no great leap of reasoning to arrive at the thesis: life itself, in its most fundamental sense, is playful.”

If one believes (as I do) that some creative concord can be reached between Genesis and On the Origin of Species, then one comes, again, to the surprising and delightful conclusion that God’s act of Creation was an act of play. On this point, scientists and theologians have reached a consensus: playfulness is a hallmark of the world we inhabit.

How might conceiving of God as playful change our relationship to Him? In Between Heaven and Mirth: Why Joy, Humor, and Laughter Are at the Heart of the Spiritual, Jesuit priest James Martin asks, “Can you allow yourself to think that the wonderful or funny or unexpected things that surprise you are signs of God being playful with you?” He continues:

Can you imagine God not simply loving you, but, as the British theologian James Alison often asks his readers to imagine, liking you? . . . How do you show that you like a friend? Maybe you tell your friend outright. Or maybe you do something generous for him or her. But you also may be playful with your friend. So can you let yourself think of the funny things that happen to you not just as signs of God’s love, but God’s like?

As someone who experienced severe scrupulosity for several years, especially acute during my mission service, the idea of God’s playfulness is a game-changer. It helps me reorient my relationship with God in healthy ways—to remember that He “likes” me as well as loves me.

Worship as Play

In LDS church buildings, the cultural hall—where rowdy games of basketball are played during the week—is directly connected to the chapel, where the holy sacrament is administered on Sundays. Though functionally distinct, with one room dedicated to play and the other to worship, these two spaces often merge when the partition is removed to accommodate overflow. In that moment, the boundaries between worship and play blur: one becomes aware of sacrament trays being passed over the painted hardwood of the basketball court, with hoops visible overhead. This blurring of spaces serves as a powerful metaphor for the unity of worship and play. Just as these two rooms can become one, so too can worship and play be seen not as separate but as one and the same.

In Johan Huizinga’s book Homo Ludens, Huizinga develops his hypothesis that the “ludic principle” or play instinct is the driving force behind all human civilization and culture, including religion. Consider that both religious rituals and play often feature elaborate costumes, are shrouded in secrecy, exist within carefully guarded boundaries in which strict adherence to particular rules is necessary, involve dramatic performances or role-playing, exist separate from the “ordinary” world, and are completely immersive. Huizinga writes, “Formally speaking, there is no distinction whatever between marking out a space for a sacred purpose and marking it out for purposes of sheer play.” To those who might object that Huizinga somehow diminishes the sanctity of religious activity by connecting it with play, he is careful to reassure his readers that the “identification of play and holiness does not defile the latter by calling it play, rather it exalts the concept of play to the highest regions of the spirit.”

Hugo Rahner echoes this claim from a Catholic perspective. He describes liturgy as a “divine game,” asserting that the Church will always embody this playful spirit. Rahner writes, “Indeed this Church, the Church of the Logos made man, will always clothe her deepest mystery in a visible cloak of beautiful gesture, of measured steps and noble raiment. Everlastingly she will be the Church that plays, for she takes the physical, the flesh, man in fact, with a divine seriousness.”

What application might this have for Latter-day Saints? Here’s one: what if, instead of thinking of service in the temple as “temple work,” we thought of our worship there as “play”? The rituals performed in the temple obviously meet all of Huizinga’s criteria for play: the ritual raiment; the dramatic reenactments and role-play; the sacred space, set apart; the secret words and oaths. The endowment is, quite literally, a drama—what we commonly call a play!

Instruction in the temple takes a playful form. Instead of passively listening to a sermon, temple patrons actively participate in a mythological drama in which worshippers imaginatively assume roles, identities, and names—kings and queens, Adam and Eve, deceased ancestors—that differ from their own. Assuming these personas involves donning strange and beautiful costuming. Temple instruction is physical rather than merely cerebral: it involves moving, standing, putting on clothes, and assuming postures and gestures. Instead of a sermon with a clear, three-point structure, the temple relies on mysterious and evocative symbols which, in their indirection, inefficiency, and ambiguity, are closely related to Huizinga’s ludic principle.

Symbols are multifaceted, resisting any simple one-to-one correspondence. Instead, they are gratuitous—their meaning cannot be exhausted. This open-endedness is at the heart of temple ordinances, where symbols act as puzzles, inviting worshippers into a deeper, imaginative exploration of divine mysteries. Puzzles have been objects of play since humankind's earliest beginnings. It is this spirit of sacred play that permeates the temple, where worshippers are invited not just to listen but to actively engage, discover, and embody divine truths.

This concept of sacred play in temple worship is reminiscent of how children learn and grow through play. A child plays dress-up and dons the costume of a police officer, firefighter, or chef. In so doing, she imagines herself someday fulfilling roles like these. She practices cooking her plastic vegetables and delivers a plate of steamy, imaginary food to a parent. This is playful, but it is also serious and important. By imaginatively assuming these roles, the child prepares in the most practical way for adulthood. Play, in addition to being fun, is transformative training. Similarly, while temple worship involves elements of play, it serves a profound purpose. By engaging in sacred play within the temple, we prepare ourselves for our eternal progression.

Some might acknowledge that play serves a practical purpose for children, but still feel that to call temple work “play” is to trivialize or infantilize something very serious and important. It’s time to challenge the assumption that play is incompatible with importance—or that it’s something only children do. Poetry, art, and music are play, but life wouldn't be worth living without them. Temple ordinances are playful in nature, but this doesn’t diminish their seriousness.

Thinking of worship as “play” aligns with President Russell M. Nelson’s invitation to “make the Sabbath a delight.” How might we make our sacrament meetings more delightful—dare I say more playful?—while maintaining the reverence that should be maintained in that holy space?

Conclusion

“Man suffers only because he takes seriously what the gods made for fun,” argued Alan Watts. We often make life harder by forgetting the joy and playfulness at its core. The gospel of Jesus Christ is not a series of checkboxes to be begrudgingly accomplished. Rather, as Makoto Fujimura has written, “the gospel is a song.” That song should course through our limbs, animating us in the playful dance of discipleship.

We’ve long understood the value of work in Latter-day Saint theology, but it’s time we begin to appreciate the importance of play. Play isn’t the opposite of work, but a complement and counterbalance—a sacred counterpart that brings lightness, perspective, and joy into the spiritual journey. As we reimagine our relationship with work and worship, we might find that divine play opens up new dimensions of faith. By bowing our heads and playing, we open ourselves to a deeper, more joyful communion with Deus Ludens, the God Who Plays.

Corey Landon Wozniak lives with his wife and four sons in Las Vegas, NV. He teaches English and Comparative Religions at a public high school.

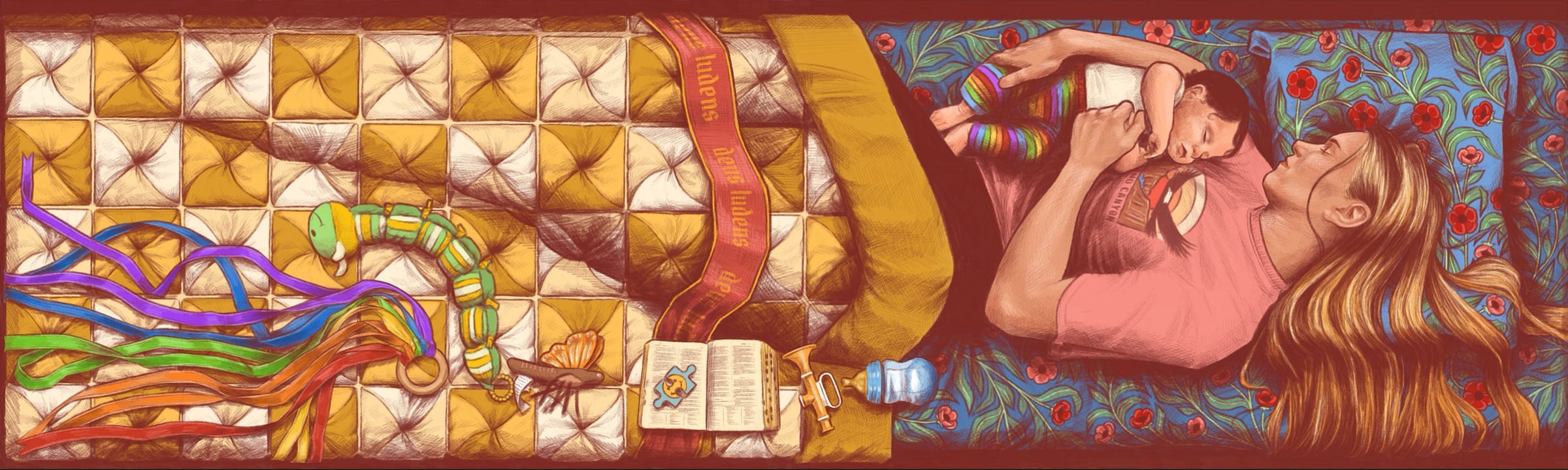

Art by Jessica Beach. Find her on Instagram @jessicabeach143.

2025 ADVENT SUBMISSIONS

KEEP READING

Fearful Symmetry

“It is not symmetry but the presence of asymmetry that best represents some of the most basic aspects of Nature. Symmetry may have its appeal, but it is inherently stale: some kind of imbalance is behind every transformation. . . . From the origin of matter to the origin of life, the emergence of structure depends fundamentally on the existence of asymm…

Create In Me A New Heart

There are some books that should require their readers’ permission before being made into a movie: for example, Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings. Likewise, I felt this way about The Wild Robot. Partly, this was because it was the first real book our oldest son read on his own. Partly, this was because

NEWS

Vote For Favorite Holiday Story

Mormon Lit-Blitz is hosting its annual holiday writing contest. Find your favorite and cast your vote!

Invitation To Apply To Eugene England Summer Institute

Eugene England Summer Institute is hosting a free, week-long writing retreat for approximately 6-8 graduate students, early-career faculty, and independent scholars working on topics related to Mormon studies. The Eugene England Summer Institute (EESI) fosters scholarship on “Mormonism,” broadly construed, through mentoring and peer support. Applications accepted January 1-February 15.

Call For Papers: Faith And Knowledge Conference

The Faith and Knowledge Conference invites graduate students and early career scholars from all Mormon traditions in the humanities, social sciences, and hard sciences to submit individual proposals addressing historical, exegetical, and theoretical issues that arise from the intersections of Mormon religious experience and academic scholarship.

Thank you so much for sharing this perspective. I am learning that living joyfully and playfully is truly the best way to make manifest and magnify God's love. But, it is often difficult to be joyful and playful when life seems overwhelming. Your article is an inspiration to me.

Oh I love this idea.

When I sing the chorus of Hymn 252, I think “we all have work, don’t be a jerk.”

“With a heart full of song” certainly seems in the spirit if play.