“It is not symmetry but the presence of asymmetry that best represents some of the most basic aspects of Nature. Symmetry may have its appeal, but it is inherently stale: some kind of imbalance is behind every transformation. . . . From the origin of matter to the origin of life, the emergence of structure depends fundamentally on the existence of asymmetries.” —Marcelo Gleiser, A Tear at the Edge of Creation: A Radical New Vision for Life in an Imperfect Universe

Snowflakes and starfish and honeycombs are beautiful because they appeal to our sense of harmony and balance—a kind of aesthetic equity. The physicist Gleiser reminds us that most development, transformation, and productive change in nature, however, comes out of asymmetry. It is the very asymmetry of human sex cells (massive ova, miniscule sperm), for example, that “leads to a cascade of evolutionary effects” that produce sexual differences in the species. The great human adventure was only launched when provocation punctured the static equilibrium of Eden.

More fundamentally, a troubling asymmetry seems not just to occasionally intrude upon, but to pervasively govern the world of human existence. This kind of asymmetry is the one that offends our moral sensibility. Nassim Taleb invokes it in its most threatening and destabilizing form: the disproportion of human influence for good and evil. In World War II, “It took seven or eight Poles to help one Jew. It took only one Pole, acting as an informer, to turn in a dozen Jews.” Instances could be multiplied endlessly from today’s news or from our own dark imaginings. No single good Samaritan can undo the damage or restore the losses inflicted by one random psychopath with a gun. The universe seems stacked in favor of pain over pleasure, evil over good.

Justice is frequently envisioned and judicially implemented in the pursuit of a harmonious and symmetrical cosmic ideal. Yet lived experience and history alike tell a different story about earthly justice. The eye-for-an-eye ethic traceable to Hammurabi was not a principle of equivalence that pretended to bring pain and pleasure back to a zero sum. If you break my arm and I break yours, we have two broken arms and two miserable victims in the universe, not zero. Hammurabi’s code had as its end the containment of cycles of retribution, not cosmic harmony. If I can only break your arm in retaliation, that minimizes the sum total of pain that your violent act set in motion. It does not make either one of us happy again. Just as witnessing the execution of your friend’s killer does good to neither one. There are very good reasons for systems of law and punishment, but restoring symmetry to a fractured universe is not one of them.

So we may have recourse to the image of Christ in his role as universal judge at the end of time. In that case, earthly justice cannot satisfy our longings for symmetry and equity, but a heavenly administrator might. He will punish all outstanding debtors to the law and comfort all the aggrieved, we may imagine. But that particular version of a Christian hope was the scenario that the great Dostoevsky so enduringly shattered. (Though not, it must be said, for all Christians.) In the famous scene from The Brothers Karamazov, the God-doubter Ivan explains his rejection of Christian solutions to the problem of human evil and its attendant suffering. He narrates the pitious case of a sadistically tortured child and declares that in spite of its tormentors’ punishment,

its tears have remained unredeemed. They must be redeemed or there can be no harmony. But by what means, by what means will you redeem them? Is it even possible? Will you really do it by avenging them? But what use is vengeance to me, what use to me is hell for torturers, what can hell put right again, when those children have been tortured to death? And what harmony can there be where there is hell: I want to forgive and I want to embrace—I don’t want anyone to suffer any more.

This may be the most piercing critique of our picture of a heavenly harmony based on symmetry—an expectation that x amount of punishment will balance out x amount of suffering, and all will be then in blissful balance. My (idiosyncratic) reading of the above words is that Dostoevsky is applauding Ivan’s inspired protest that our quest for cosmic parity and equity in some zero-sum kind of way cannot be the end of true religion—here or hereafter.

Centuries earlier, another writer offered his own complication in our craving for a symmetry of suffering and retribution. In a seldom quoted passage in his twelfth-century commentary on Romans, the monk Abelard raised a problem that faintly anticipated Dostoevsky’s doubts about hell balancing out heaven. Abelard pointed out that good and evil themselves are not always simple, symmetrical categories. That good men and women can do terrible things. Christ predicted this messy future for Christianity (including our own tradition): “an hour is coming when those who kill you will think that by doing so they are offering worship to God” (John 16:2 NRSV).

Where, asks Abelard, are we to find resolution when the well-intentioned do hurtful and destructive things in good conscience.? In his era, Christians were killing Muslims—and they had long been killing other “heretical” Christians. How can that suffering be avenged or harmonized if there is no ill-intentioned perpetrator to punish? “For if they had shown mercy,” writes Abelard, “they would have acted against their conscience and so would have sinned. But again, since they killed the innocent, indeed, the chosen of God, which is unjust, shall we say that they do not sin? Or that they have a good intention in this which goes very wrong?”

Abelard does not resolve the problem. Neither can I. Yet I do believe that the solution—as Christ’s Incarnational Reconciliation (“atonement”) seemed designed to demonstrate—must have at its core a powerful asymmetry. Owen Barfield writes that something is different about the divine love manifest in Christ. Jesus, he writes, is deliberately “outraging” our “deep-rooted feeling for the goodness of justice and equity . . . because we are being beckoned towards a position directionally opposite to the usual one…. to experience the world of man as the object of a huge, positive outpouring of love, in the flood of whose radiance such trifles as merit and recompense are mere irrelevancies.” “There is,” echoes Marilynne Robinson’s Reverend Ames, “no justice in love, no proportion in it.”

I see a Christ at greatest pains to reshape the moral universe of a people who are genetically, socially, and culturally disposed to demand fairness, equity, symmetry, and due proportion in human relationships—and in the universe generally. Perfect love overflows all those bounds. “Are you envious because I am generous?” is the question that undergirds Christ’s conspicuous refusal to apportion love by any limiting criteria or categories (Matt. 20:15). As Anders Nygren wrote, “it is of the very nature of forgiveness that the one forgiven does not have a right to be forgiven.” What is forgiveness, if not the most perfect expression of this asymmetry?

Terryl Givens is Senior Research Fellow at the Maxwell Institute and author and coauthor of many books, including Wrestling the Angel, The God Who Weeps, and All Things New. To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

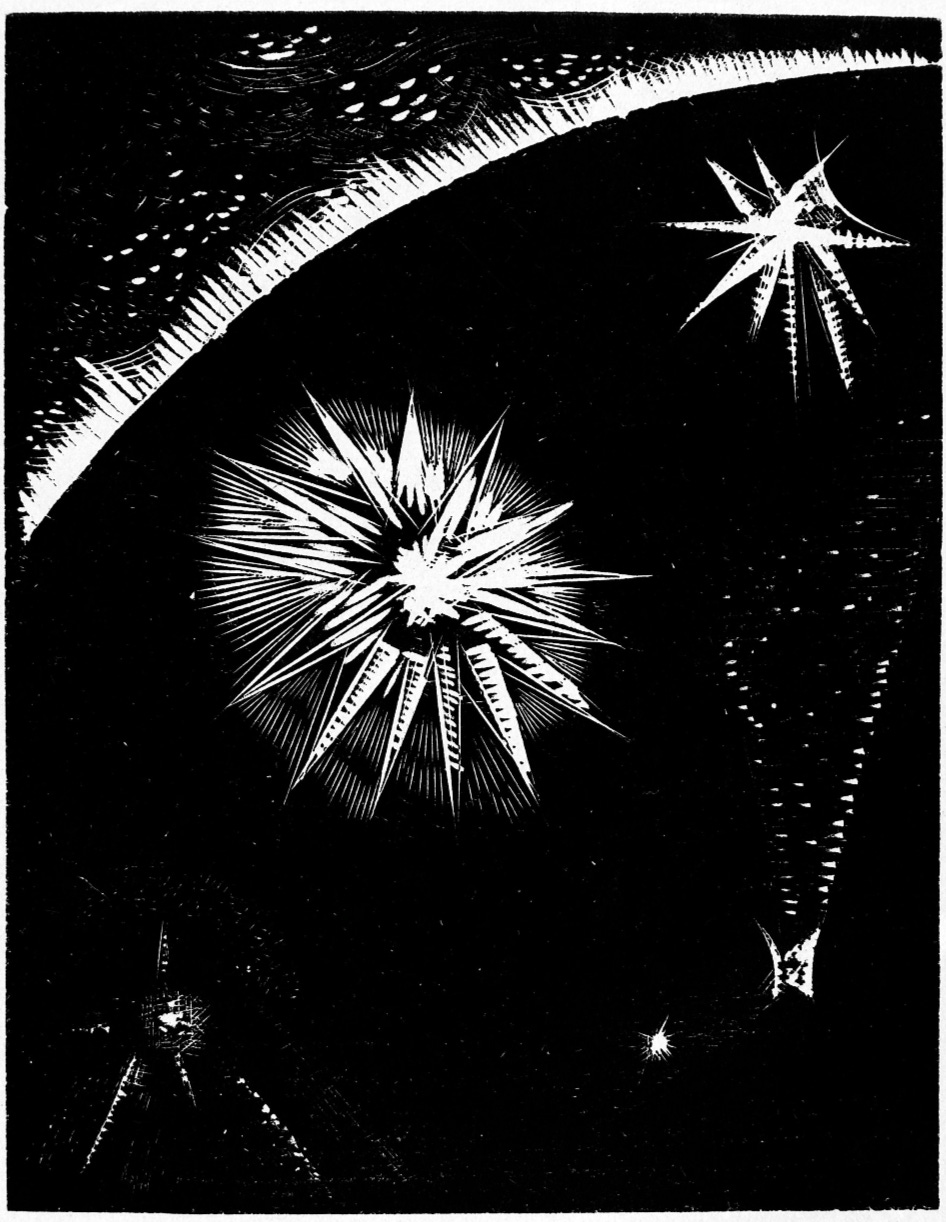

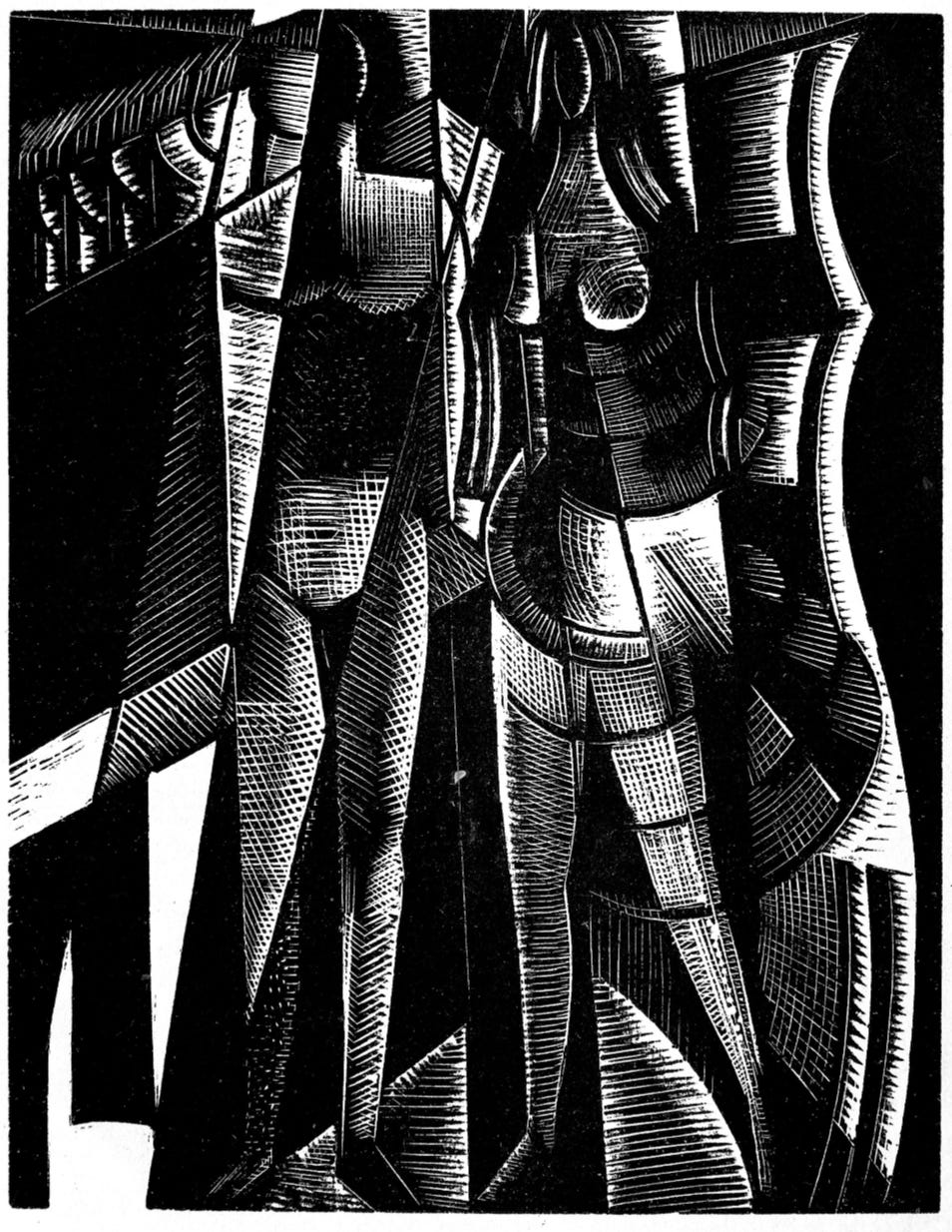

Art by Paul Nash.

Audio produced by BYUradio. Subscribe to listen at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or Youtube.