Milagro

When God Sees Me

“A miracle is an extraordinary event caused by the power of God.”

I do not have a theology of miracles. This is evident when considering what I told my teenage daughter recently. We were reading the Book of Mormon early one morning before school, and as she came to Nephi II’s miraculous declaration that the chief judge had just been murdered, she gasped. Then she looked up at me and in perfect Spanish asked me why there are no such miracles in our day and age. The question caught me off guard and, as one is wont to do when one lacks a theology of miracles, I simply paraphrased what I had read before: that miracles had not ceased. I quickly searched my mind for contemporary examples and rehearsed a few stories I had heard from Official Church History. I wanted to also point out some miracle she might have witnessed but drew a blank. The type of swirling-pillar-of-fire, little-girls-coming-back-from-the-dead miracles I wanted to tell her about just were not there.

To be fair, there have been things in my life and the life of my loved ones that can only be described as miraculous, but these tend to be intimate and are usually not shared. In part they tend to not be shared because, unless you lived it, most people would raise an eyebrow or even scoff. We are, all of us, children of the Scientific Revolution, after all. We trust the basic premises of the Age of Reason. Because we are now largely empirical in our thinking, we expect everything to have an explanation. Every effect we see, we expect to have a cause that can be discovered through observation. Where pre-Enlightenment peoples would have seen a miracle, in our mind frame we seek out rational explanations. The ancients saw the Nile turn to blood, but we moderns are more likely to believe that it was a red tide—a “harmful algal bloom.” And the frogs everywhere? Whirlwinds that picked up frogs from the river and dumped them every which way. We could go on and on like this, but that is the basic gist—when someone in the modern world witnesses something miraculous, there surely is a rational and enlightened explanation that does not include divine intervention. In short, as non-medievals we tend to not see miracles because we are ever on the lookout for naturalistic and probabilistic explanations that will relieve us from the awe and fear of an unseen world we cannot fully grasp.

But sometimes, we experience things. Extraordinary things. Things we simply cannot explain. It may be an impossible near hit on a highway. Or a perfect stranger comforting us in a mall at a moment of grief he could not have known about. Perhaps someone dearly beloved suddenly becomes healthy again. In our post-Enlightenment age, though, people who experience the miraculous in this way tend to not share it, except in safe spaces surrounded by fellow believers.

So, I do not have a theology of miracles. I only know that sometimes things happen that cannot be explained, and in very intimate ways, these things can have the power of moving us to experience, as did Hagar the primitive, a divine presence, one that can only be described as El Roi, the God Who Sees Me.

The story I am about to share is one such El Roi story. It is, like all these stories, very personal. To understand it, some context may be helpful. At the time, my family lived in Quito, Ecuador. This was in the 90s, and we were there because my father had been transferred to foreign Ecuador from our native Uruguay by the Church Educational System. We were strangers in a strange land, so to speak, but we loved that land. We grew to love Ecuador’s people and felt great sympathy for the country’s large Indigenous population. There was an Indigenous family out of Otavalo in our Spanish-speaking ward in Quito, and my mother felt a kind of spiritual kinship with the wife in the family, who despite her husband being inactive brough her children faithfully and quietly to Church every Sunday, as well as friends and other relatives from time to time. It was during those days that something happened, a small quiet thing. She related this story to us, her children, because we weren’t home when it happened.

I wrote it down in Spanish, and now I share it with permission. I share it first in the original Spanish, because there’s something in the voice of one of the sisters involved that can only be fully captured in the language in which it happened, but I’m also providing a self-translated version for readers of English. This story is what I really should have related to my daughter when she asked me about miracles early that morning, but at the time, I fell back on default answers. What I should have told my daughter is that I do not have a theology of miracles, but that something happened to her grandmother once…

«No quiero que usted se vaya, hermanita»

Por aquellos días, Zulma empezó a sentir que languidecía. Experimentaba un letargo carente de fiebre o dolores, un letargo solamente. Aquel estado iba acompañado del remordimiento de ver pasar los minutos como horas, sin hacer nada. Se echó en la cama a mirar cómo pasaba el tiempo sobre la tarde quiteña. Recostada en aquella cama, supo que se moría. Como quien se queda dormido sentado, así se moría.

Entonces sonó el teléfono que tenía sobre la mesita de luz. Era una hermana del barrio, una otavaleña que hablaba mejor el quichua que el español y que junto a su marido cuidaba de un taller mecánico. «¿Hermanita, usted está enferma?», le preguntó a Zulma sin dar explicaciones. No llegó a pasar una hora cuando la otavaleña estaba en casa de Zulma. Se sentó al borde de la cama y le dijo que había tenido un sueño. En el sueño, el esposo de Zulma y sus hijos se iban de Quito en una carreta. Se iban solos, sin Zulma, y llevaban algo en la carreta tapado por un mantel blanco. La hermana acariciaba la mano de Zulma con lágrimas en las mejillas, y le dijo: «No quiero que usted se vaya, hermanita». Le explicó que traía unas hierbas y sin más se metió en la cocina a preparar una infusión. Llevó el agua aromática al dormitorio cuando llegó el esposo de Zulma. La hermana otavaleña le dio el tecito a Zulma y les explicó que iba a hacer una oración. Se puso de rodillas y en un léxico directo, con semántica sencilla, pronunció una bendición de fe. El dormitorio ardió. Luego la hermana otavaleña se retiró tan súbitamente como había aparecido.

Unos días antes, Zulma había visitado a un médico que le mandó a hacerse unos estudios. Esa tarde, unas horas después de la visita de la hermana otavaleña, el médico llamó a Zulma a fin de darle un diagnóstico. Le habló de una «bacteria asesina» que sólo podía ser tratada con un antibiótico de extrema agresividad. Zulma debía internarse sin demora para que bajo supervisión médica profesional le administraran a cuentagotas el remedio a lo largo de cuatro días. Zulma accedió.

Casi enseguida sintió la necesidad imperiosa de ir al baño. Allí liberó una orina marrón oscuro que en la taza del inodoro parecía cuajarse en una especie de tela casi negra. De inmediato Zulma se sintió mejor. No necesitó internarse y, tras nuevos estudios, el médico le confirmó el milagro: ya la bacteria no estaba.

“I don’t want you to go, my sister”

Those days, Zulma began to feel she withered away. She felt a sort of lethargy devoid of fevers or pain. It was just lethargy. That condition carried with it the guilt of watching minutes stretch into hours while doing nothing. She lay on her bed to watch time pass over the Quito afternoon. As she lay in her bed, she knew she was dying. She was dying like someone might doze off while seated in a recliner.

Then the telephone rang on her nightstand. It was a sister from the ward. She was originally from Otavalo and spoke better Kichua than Spanish. Alongside her husband, she watched over a mechanic’s shop for a living. “My sister, are you sick?” she asked Zulma without any preambles. In less than an hour, the Otavalo sister was at Zulma’s house. The Otavalo sister sat on the edge of Zulma’s bed and said she had had a dream. In it, Zulma’s husband and her children were leaving Quito on a wooden cart. They were leaving by themselves, without Zulma, and they carried something on the bed of the cart that was covered by a white tablecloth. The sister started caressing Zulma’s hand, and tears rolled down her cheeks as she said, “I don’t want you to go, my sister.” She proceeded to say that she brought with her some herbs and without further explaining went to the kitchen to prepare an infusion. She was carrying the herbal tea into the bedroom when Zulma’s husband arrived. The Otavalo sister gave Zulma the warm beverage and stated she would pray. She knelt and with straightforward words, in simple terms, pronounced a blessing of faith. The bedroom was aflame. The Otavalo sister then left as suddenly as she had arrived.

A few days earlier, Zulma had gone to the doctor. He had instructed her to get some tests done. That afternoon, a few hours after the Otavalo sister’s visit, the doctor called Zulma with a diagnosis. He spoke of a “killer bacteria” that could only be treated with an extremely aggressive antibiotic. Zulma was to check into the hospital at once so that medical professionals could supervise the administration of the medicine using a dropper over four days. Zulma said that would be fine.

Straight away, she felt the imperative need to go to the restroom. There, in the toilet bowl, she released a dark brown urine that seemed to coagulate into a nearly black fabric of sorts. Zulma immediately felt better. She didn't need to check into the hospital, and the doctor, after running some further tests, confirmed the miracle: the bacteria was gone.

Gabriel González Núñez is the author of several children's books, a short story collection, and a poetry collection. He is a professor of translation at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. He was born in Uruguay.

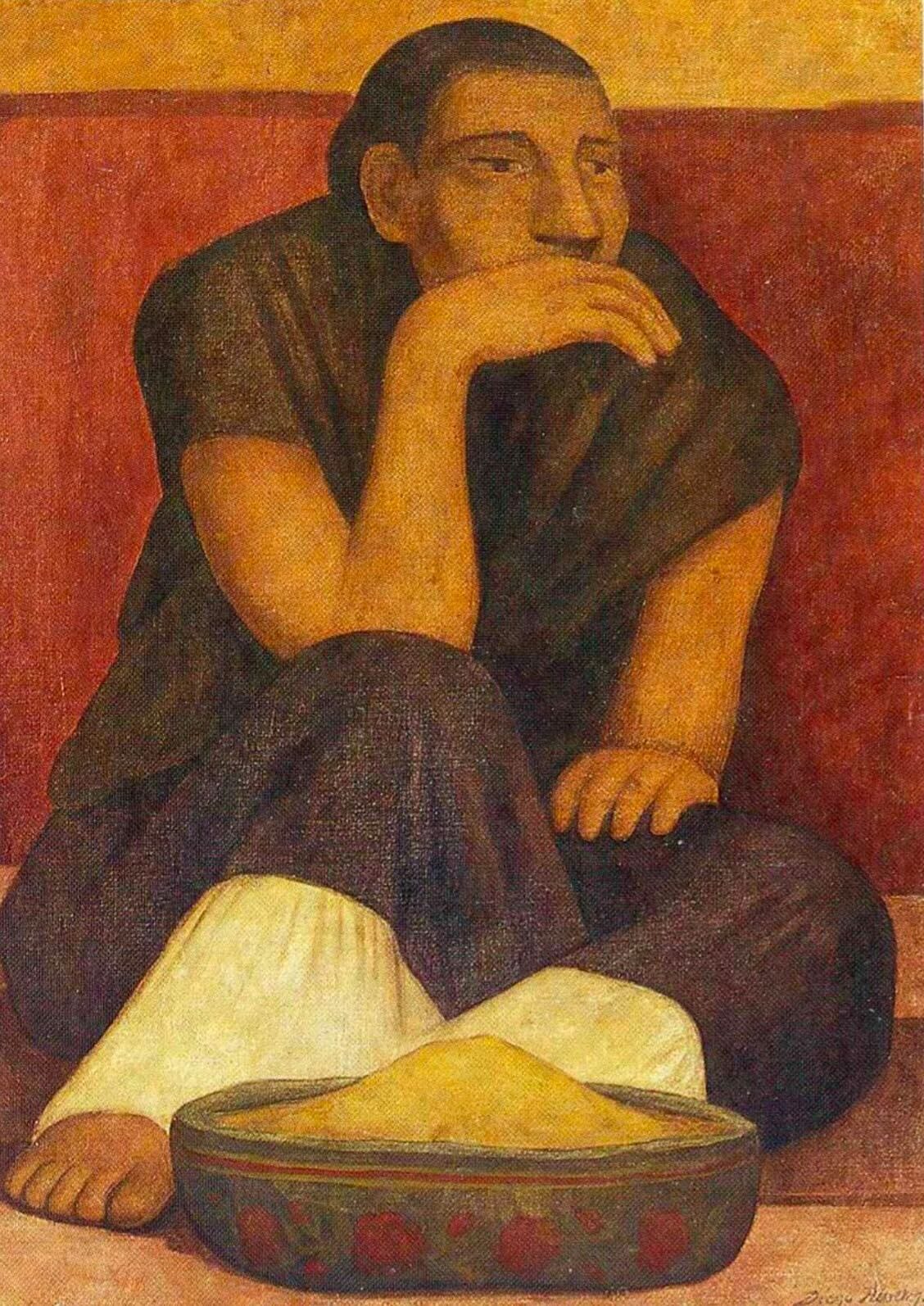

Art by Diego Rivera