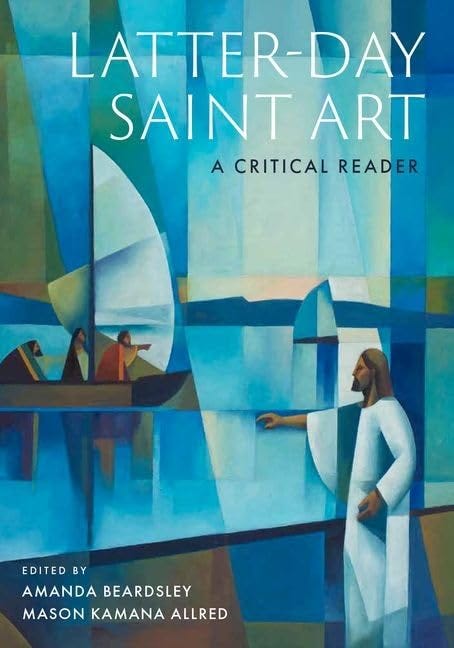

Jenny Champoux: Hi, everyone, and welcome back to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux. In Latter-day Saint Art, I'll guide you through an examination of the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts.

Please note that a transcript of each episode, along with images of the artworks discussed, is posted at wayfaremagazine.org.

In this episode, we'll learn about efforts by early Utah artists to improve their skills and stay connected to the cosmopolitan art world. For many, this meant traveling back east to New York. For some, it meant traveling all the way to Paris, France. The experiences and training they gained there would affect Utah art styles and culture for years to come.

We'll also discuss mid-20th century opposition to avant garde [00:01:00] movements, like modernism, in Utah and reflect on whether that history still influences Latter-day Saint preferences today. Our guests in this episode are Glen Nelson and Linda Jones Gibbs.

Glen Nelson is a co-founder of the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts, and he hosts the Center's podcast. He is the author of 33 books, as well as essays, articles, short fiction, and poetry. As a ghostwriter, three of his books have been non-fiction New York Times bestsellers.

He curated the museum exhibition John Held, Jr. at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art, and co-curated Joseph Paul Vorst: A Retrospective, at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City, Utah. His most recent books include the first biography of Joseph Paul Vorst and a volume about the lost fiction of John Held, Jr. He has two chapters in this new book. One is, “LDS Artists and the Art Students League of New York,” and [00:02:00] the other is titled, “George Dibble and Modernism in Utah.”

Linda Jones Gibbs, an independent scholar living in New York, has a PhD in art history from the City University of New York, with specialties in American and modern art. She was a former curator at the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City and at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art. She has written extensively on American artists in France and on the artist Maynard Dixon. Her essay in the Oxford volume is, “The Paris Art Mission.”

Glen and Linda are both passionate about studying Latter-day Saint art history and teaching others about it. I guarantee you're going to learn something new from them today. So, let's get started!

Linda and Glen, thanks for joining us on episode three of Latter-day Saint Art.

Glen Nelson: Thank you for having me.

Linda Gibbs: Thank you so much.

Jenny Champoux: I'm so delighted to get to talk to two of the best scholars [00:03:00] helping to recover the history of Latter-day Saint art. I think the events you highlight in your chapters are not well known to most members, but it's important history that really helps us understand the development of our visual culture. So, I'm grateful to you for the good work you're doing.

Linda, I want to start with you. You were working at the Church History Museum in its earliest days in the 1980s and then also at the BYU Museum of Art when it first opened in the 90s. So as someone who's been part of the development of this field studying Latter-day Saint visual culture, really since the beginning in those early days, what, what changes have you since then, in terms of how we're thinking about Latter-day Saint visual culture and do you see any areas that you think need further exploration and scholarship right now?

Linda Gibbs: There's been a wonderful explosion since those early days. When I first started working [00:04:00] at the church historical department, the art collection was uncatalogued and unknown, as was BYU's collection. If you go back to really not that long ago, I mean, it is what, 35 years or so, the present, there's been a tremendous expansion of knowledge and scholarship, a great infusion of interest in women's art, in international LDS art.

I see it only getting better. As artists, as the church grows and expands and artists are highlighted in various venues in Utah. I don't really perceive of big gaps at this point. I see it just a wonderful expansion.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, it is a really exciting moment. And Glen, I think you have a lot to do with [00:05:00] that as well. You have the distinction of having two chapters in this book. And you also helped write the foreword along with Richard Bushman. The book itself wouldn't have happened without your longstanding commitment to the study of Latter-day Saint art.

Can you tell us a little bit about your work at the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts in New York and how this book grew out of your projects there?

Glen Nelson: Well, I'm happy to. I don't know if I can remember it very well, um, but Richard Bushman, contacted me. He had worked with me previously when I, I had an organization called Mormon Artist Group for a few decades. And he said, let's get together and see what we can do with visual art. If that appeals to you.

And I said, yes, it appeals to you very much. And so we had a list of big projects to do. And one of them was to try to figure out what the canon would be, but also thematically what the canon might be. So there were greatest hits for sure. There were usual suspects [00:06:00] for sure. What weren't we kept covering and what was still to be discovered? And so one of the things that I'm happiest about is gathering these scholars. We made a list of people who have PhDs in art history or who were teaching at the university level or were executive directors at museums, that sort of level. And there were about 50 of them. And the majority of them didn't know each other, didn't live close to each other. And so when this book came about, it was kind of a social experiment. Can we get people together? Can they write about stuff that they actually care about? Not assigned to them, but what they really care about, and then it all evolved from there.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I love that you had the authors really tackle projects that they were passionate about, and I think that really came through in the book, that there's just, there's such variety and, but the passion really comes through and it gives you a sense of how much there is still to [00:07:00] explore in this history.

Glen Nelson: I think there are lots of holes, and anybody who travels the world knows that it's impossible to write a global story of anything. But I don't think of this book as being the be all and end all, the final word on anything. I, but I do love it as being an initial resource.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, thank you. All right, so let's get into your chapters from the book. Linda, yours is on the, your chapter is on the Paris Art Mission of 1890, and, I know you were involved with an exhibition years ago at the Church History Museum, and I think you wrote the catalog for that exhibition as well, is that right?

Linda Gibbs: I did. It was 1987. It was called Harvesting the Light: The Beginning of the Paris Art Mission - artists, missionaries.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, yeah, it's a beautiful catalog and I love that you were able to draw on your previous scholarship and expertise [00:08:00] to write this excellent chapter. So for those who aren't familiar, can you tell us what, what was the Paris Art Mission? Why were Church leaders wanting to send members of the church to Europe to study art?

Linda Gibbs: So their, their wanting to send was really a response to a request, a very fervent request by a group of artists, most notably John Hafen, who wrote to the First Presidency after actually met with George Q. Cannon of the First Presidency in 1890, and he said, you know, we've got this beautiful temple that's about to be completed. It had been under construction for 40 years, the Salt Lake Temple. What are we going to do to decorate the interior? Now, the three previous Utah temples, Manti, St. George, and Logan had murals. So it was an expectation that the Salt Lake Temple as the crowning jewel in the temple environment [00:09:00] should have murals and nothing had been discussed.

These were artists who were getting their training as best they could in Utah. I think they had a dual motivation in mind. One was, of course, to be able to paint the murals in the Salt Lake Temple, they also, I believe, saw this as a way they could get some training by requesting that the church send them to Paris to study, get their skills improved so they could come back and really do justice to the Salt Lake Temple. And so they fervently asked the Church to consider the request. This is in the 12th hour. You know, the dedication is coming up and no murals are on the walls and within weeks, the Church presidency came back and told John Hafen [00:10:00] we will send you. And so they had to work out some details of the money and whatnot.

And, within, gosh, a few months, they were on a train to New York and on a ship to Liverpool and on another to Paris.

Jenny Champoux: Wow.

Linda Gibbs: So it was quite a quick dramatic story.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, so you mentioned John Hafen. Were there other artists involved in this group?

Linda Gibbs: Yes, the initial group was four artists, John Hafen, John B. Fairbanks, Edwin Evans, and Lorus B. Pratt. They were all friends. They knew each other just through the art world in Utah. And then, later on, they would add a fifth, Herman Haag, who came, the following year and, very young, 19 years old, I believe the age of missionaries, but he, this was not a typical mission by any means, but they were, it was called an art mission because they were [00:11:00] literally set apart by the General Authorities of the Church and given this express charge to go see all that they could see, learn all that they could learn in order to glorify the kingdom of God in Utah. And so they, they were told, learn and see all that you can be careful. You know, don't see too much. I mean, it was a weird kind of, charge to really throw yourself into the world but kind of keep some boundaries. You know, this is a mission after all.

Jenny Champoux: What an interesting thing for them to have to negotiate. Yeah.

Linda Gibbs: Yes.

Jenny Champoux: And then Glen, it was just a few years later, I think 1899, that you recount how artists also started traveling to New York for the Art Students League in New York. And I think over a period of years around that time, you [00:12:00] said about a hundred members of the Church were coming from Utah going back east there. So tell us what, what is the Art Students League? Who are some of these artists that were involved from Utah and how, how would it compare to the Paris Art Mission? Was the Church supporting these artists in the same way or was it more of an independent project for them?

Glen Nelson: Well, I have to say before I say anything else, how much I love Linda's work.

Jenny Champoux: Oh,

Glen Nelson: I grew up with that Paris missionary story thinking, well, that would be cool. They should send me to, you know, but, I love that story. And I'm surprised that more people don't know it now. I'm, I'm a little concerned about that, actually. And so when I started thinking that there might be a story in the Art Students League of New York and LDS artists, I reached out to Linda and I said, how might this be different than the Paris experience? And so I'm grateful to you, Linda, for helping to shape some of my thoughts on it. But as I came across the biographies of a lot of [00:13:00] well known artists.

They would be like Mahonri Young, Minerva Teichert, and LeConte Stewart, and George Dibble, and Louise Farnsworth, Mary Teasdel, all of those people, Mabel Frazer, some others. They all mentioned how important the League had been to them. I thought, I wonder if there's a story here. And I do wonder how it would differ from the Paris experience.

So, it's quite a contrast. It started, the League started in 1875, so 150 years ago. Its purpose was to basically teach artists, especially about drawing the figure. And it was a certified program, and once people had this, under their belt, they were more employable. And so it was for a long time, one of the few places that you could really go the U.S. to be serious about it. Previously, you went to Paris or you went to Munich and you went elsewhere. But after world during, you know, world conflicts [00:14:00] that didn't become possible to travel abroad as much. And so New York really became became paramount. So what I found was these nearly 100 artists are all over the map stylistically. But they have a lot of things that they could accomplish that Paris couldn't accomplish. For example, the women, a lot of women studied at the Art Students League, and many of these students became faculty people eventually at the Utah schools and elsewhere. And so the ethos of the Art Students League, which were quite distinct from Paris shifted, their thinking and sifted into their ways of teaching.

So those were the basic, the germs of an idea that I had and what struck me as I got deeper and deeper into it was that it was a really important moment. And maybe to my mind, one of the largest outside sources, cultural sources of influence on the [00:15:00] culture, on the LDS culture.

Jenny Champoux: That's so interesting. Yeah. I, I want to get back to that point about the long-term effects on the culture, but, but first let me ask about some more of the technical art skills that they learned. It seemed to me that both of you pointed out at the art students league and at the Académie Julian in Paris, there's this real emphasis on, draftsmanship or drawing, like really technical, good drawing as a foundational skill.

Was that different than what they were able to learn in Utah? Was there anything like that in Utah? And I know often along with that, it was being able to draw from live models, sometimes nude models. Was there anything like that available in Utah or could they only get those experiences by going back to these other schools?

Linda Gibbs: I doubt very seriously, right Glen, that there were new models in Utah in the 19th [00:16:00] century.

Glen Nelson: Actually, Mahonri [Young] in his bio talks about hiring sex workers to be models.

Linda Gibbs: That's so, and I read that. I thought that was fascinating. Yes. So they did not, no, they did not have the regimented, skills. They probably did a lot of copying of engravings and other paintings. Maybe they had clothed models. I can't recall of anything by any of the Paris art missionaries doing figure, figurative work, I'm sure they did, but, I think it's interesting, and I really loved your chapter, Glen, and as I pondered it, I thought it was kind of interesting that it both, certainly differences between the Julian Academy and the Art Students League in terms of the professorships, the instructors. But in both cases, there were diverging trends.

You had, teachers at the art students league, [Robert] Henri [00:17:00] versus Chase, who had very different approaches. In Paris, some of the teachers had very different approaches, which allowed the students to kind of pick who they wanted to follow or a regiment they wanted to follow. And Henri at the Art Students League, was in Paris for 12 years on and off.

So he's bringing some of that back, but I think he certainly, his philosophy was certainly follow your own artistic path and did everything he could to encourage it. And that maybe was not the case in Paris. It was more adhere to the rules.

Glen Nelson: Yeah. And I would say too, that you had asked earlier, Jenny, about the Church's sponsorship. One of the aspects that made New York so interesting to me is how much they sacrifice to be there. And the same is true for Paris, but they didn't have there was no subsidy to come to the Art Students League. Like, these people worked a long time, even [00:18:00] to work, even to work in New York for a semester. That's how valuable it was to them.

Another difference between the two is in New York. There was an expectation that the students, and this was true for the students from the Mountain West, really immersed themselves into the city and hang out with other people and, and be influenced by them, not just their art. And the teachers were extremely approachable. There are lots of stories about, you know, just hanging out with them at night and so that formality broke down in, in the American school.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, and Glen, along with that, again, you mentioned some of these lasting effects that this experience had on the Latter-day Saint imagination, and not just in terms of the art styles they brought back, but just, how did these students, their experiences or their education there, how did that transfer back to Utah? What effect did it have on the larger culture?

Glen Nelson: Well, let's talk about women. So, in, [00:19:00] you know, 150 years ago, it would be quite unusual for an arts organization to say, all right, half of the board of directors from the first day have to be women. Part of the, that was part of the, the charter. So there were divisions. I mean, every once in a while for, for in the earliest days, if you had a nude model, the men and the women drew separately. But there weren't that many distinctions and breakdowns of things. And so just that as a fact that women were invited to be part of it. And, and I think you're right too, uh, Linda about Henri's tell your own story and he would tell that he told that to everybody Minerva heard it differently.

Linda Gibbs: Right,

Glen Nelson: heard it as a mission call,

Linda Gibbs: right.

Glen Nelson: And that trickles down into our culture, that, the Mormon story is validated and worth talking about, and that prejudice didn't really happen to these artists in New York. I, [00:20:00] I don't know about Paris. And then the other thing, stylistically, is there are these two large schools in the earliest days of the the Art Students League, the Paris school, which was quite precise, as you were saying earlier, and the Munich school, which was not that. And, and, and Henri's part of that school, actually stylistically, it's darker, it's messier, it's more emotive. And so the, the precision of creating the figure is less important than the impact of seeing the figure depicted. And so as, so as students from the West returned, they both embraced. In their schools that you could have multiple points of view, and that none of them should be supreme and that a student should be able to pick and choose how he or she wanted develop.

So, I think those fascinating, like, years ago, these things were already in place, and they had a huge impact that ripples out. Over our culture. And the, the, the biggest example, the [00:21:00] most ready example is University of Utah, where you've got Mabel Frazer butting heads with LeConte Stewart, and, and both of them are, are people from the Art Students League.

Jenny Champoux: So they're coming back with greater, maybe freedom to feel like they can use their own styles, take their own approach. But also they felt maybe able to embrace their own faith in their art. Because they'd had that validation there. Like you said, they weren't, the mentors and teachers, there weren't prejudice against them for for their beliefs and even encouraged them to lean into that perspective, their own experience.

And then I love what you said about the women too. That the women felt empowered in a different way and brought that perspective back to Utah.

Glen Nelson: I’m curious, Linda, to know about how this worked at the Académie Julian, but in New York. It was kind of an even division between the artists who were [00:22:00] professional and were serious about it and those who were just hobbyists and wanted to paint for a little while. I don't know if that's the same in Paris, but I think that helped with it helped in New York, bringing a whole lot of different kinds of viewpoints into a classroom.

Linda Gibbs: When the art missionaries were at the Julian Academy, there were 1,500 other Americans there. And would guess that what it took to get there would imply that they were pretty serious about wanting a career. There was, as an aside, there, there were classes for women that were segregated from the men. But no Utah woman, the only Utah woman who was there was Harriet Richards Harwood, who, who marries James T. Harwood, who was the first Utahn to go to Paris. There were several that preceded the art missionaries. I don't know that she formally studied, [00:23:00] uh, at the academy. But just to answer your question, I, I think, think they weren't there on a lark.

Maybe some of the Europeans were, that were, but the Americans, I'm sure we're all trying to have that as a, you know, as a gold star in their resume to have studied there.

Glen Nelson: As I was reading your chapter, Linda, I was struck by the idea of the landscape.

So the, the art missionaries went, went off into the countryside and did a lot of painting. I don't think that happened in New York. And I'm curious, the New Yorkers returning, other than other than Stewart, who really is essentially a landscape painter. There really aren't that many that focused specifically on the landscape. And I wonder if that might be another byproduct of their training.

Linda Gibbs: In the, you mean, the, the students at the Art Students League, not gone in the landscape. No, I hadn't thought about that. [00:24:00] I think that's an interesting thought. Of course, Stewart does. And to some degree, Mabel Frazer, Teichert is so narratively sourced, I don't think she would count as a landscape artist. Perhaps you're right. I mean that, I think the Paris art missionaries were far more influenced long term by their ventures into the countryside than they were by their studio work, which is true for a lot of the, of course, the French and European artists, too.

Jenny Champoux: And of course they are there to train to do murals in the temple, like a garden room, right? That a lot of what they're going to do when they return is that kind of landscape painting. Linda, after they do the temple murals, what did these artists go on to do? Was that the end of it for them? Did they go on to have artistic careers in Utah?

Linda Gibbs: Oh, they did. They, [00:25:00] many of them were teachers. Hafen started the, what is now the Springville Art Museum, uh, by a donation of a painting to Springville High School. They started arts organizations. They held annual or semi-annual exhibits that, according to the newspaper clippings of the time, people came in droves to see their art.

So there was this real injection of enthusiasm and interest, think, in still quite rural community for the fine arts as a direct result these art missionaries bringing back the influence of European painting.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, and I see that preference for Impressionist landscapes still today in, in Utah art, being produced and collected today. Do you see that as a direct, I don't know, result of these early art missionaries and [00:26:00] their Impressionist landscapes?

Linda Gibbs: It’s probably more a result of just the ongoing love affair that we Americans have with Impressionism. I mean, I, I think it was too long ago for it to be a direct connection, but it's just, it's still, I mean, you go to the Metropolitan Museum today, Glen, and where are all the people there? In the Impressionist exhibits. So it's not, I don't think anything that's unique to, to Utah.

Jenny Champoux: Interesting. Yeah. So to shift gears a little bit, Glen, you also wrote a chapter on George Dibble. He was a mid-20th century artist, who also studied at the Art Students League, but unlike many of those other students that came back to Utah and found success, it sounds like Dibble always struggled for acceptance.

He had a very modernist style, and you see this as kind of [00:27:00] an example of how Utah culture can be resistant to artistic change. What were some of the main concerns that people in Utah or even in the institutional church had about modernist art at that time in the mid-20th century?

Glen Nelson: Well, it wasn't just Utah, of course. America kind of hated modern art. It started in 1913 with the Armory Show here in New York that actually was, it's sort of funny. Mahonri Young was one of the very small group of people who got that together and was part of the show. But modernism just really freaked out America. And they did not understand it, did not like it. They, it was more than just stylistically. They, ascribed really negative terms to it. It was communist. It was, it was, atheist work. You couldn't be a religious person and modernist, they would say. And this was not just cubism, but the whole, the whole early 20th century, [00:28:00] styles of, of creating work. so, if you're a Utahn, who's a good member of the Church, and you have no real exposure to it, and then you come out to New York, as Dibble did, and he went to Columbia, as well as to the Art Students League, he said he found his voice. He said he was a landscape painter, but his way is, turning, he's a by nature. And so turning modernist lens and a watercolor lens onto the landscape gave him this whole new way of working. So he was teaching at the time at the University of Utah, and LeConte Stewart hated modernism, hated it. And so he wasn't, and so Dibble didn't get promotions. He didn't, he, he felt that he had to paint a certain way. And, he, but meanwhile, he's the art critic for the Salt Lake Tribune for 40 years, and he doesn't have an agenda. He loves artists, and anything that they do that he thinks is valuable, he'll promote them. [00:29:00] So, then finally, when LeConte Stewart died, basically, then he felt unleashed and created the work that he's most known for. But, you know, he had people in the Church approach him who were artists. And say, listen, we worry, we worry for your soul, you’ve got to give up this modernism. And it sounds kind of weird. Like a hundred years later, we're still having this discussion. We're still having this discussion. There are a lot of artists and a lot of other people, the Church, in Utah and elsewhere. Who just don't think this is a thing of value and the story.

If you don't mind the story that I found the most illuminating is, Dibble was getting ready to create a book on the techniques of watercolor, and he wanted to use an image of his own that was quite well known, and it won some prizes at the state fair, and it ended up being at Utah State. And so he went up to Utah State and Logan, which [00:30:00] was at the time, the most progressive of the art schools regarding modernism in Utah, he was, he didn't have a good image of it, so he wanted to go get a nice image and he couldn't find it and the museum didn't have it and the university didn't know where it was.

And all the paperwork was lost. So he's dejected as you can imagine, because this is the breakthrough image for him. Cedar Breaks No. 2 is the title of it. It's a beautiful, beautiful image. It's not just because I'm from Cedar City. Anyway, so he, so he's leaving dejected and he walks by the janitor's office and the janitor has that watercolor pinned up on the board he says to the janitor, obviously, I won't use the language that he probably felt justified using, but, how did you get that?

Why? Why is that here? And the janitor said he fished it out of the garbage. So, when I'm saying that artists felt like that, they weren't accepted. This is a whole other level. These are artists and institutions and museums who [00:31:00] are shutting these things down. This is, you know, this is tough stuff. I, in my opinion, this is censorship at its at its highest level.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah.

Glen Nelson: So that's that, that's the, that's the very long answer. I apologize for being so windy here, but I, I really liked Dibble a lot and he's an excellent example of how the, how the Church still really, really struggles with this. Even at the Church History Museum, for example, you know, to get, to get an artwork into that show that's modernist is really quite difficult.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. We have such a longstanding tradition of figurative and narrative art that that's officially used by the Church. It seems like, yeah. So, but despite this pushback, you described how some artists in Utah were still trying to experiment with this modernist style and they actually wrote in the early 1940s a manifesto.

What was in this manifesto? What were their [00:32:00] goals?

Glen Nelson: Oh, now you're quizzing me. This doesn't seem fair. Linda wasn’t asked to quote stuff or to speak in French or anything, but the manifesto generally, was to say we exist and we're curious and let, don't shut us down. In my chapter, I, I compare this to the abstract abstract expressionist in New York, who wrote a manifesto at the roughly the same time, which is extremely combative. You don't like our stuff. Get over it. Like we're here, you know. In Utah, it's a little bit more placating, I think, but yeah, the manifesto was basically an invitation for other people look at their work with a little more curiosity.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, and you describe this in a little bit more detail in the book, which I really appreciated. And two of the things that stood out to me there were, yeah, that is just freedom of thought that they wanted to have freedom of thought and also of stylistic expression. And [00:33:00] then, just this emphasis on, on the formal elements, right?

On the actual interplay of canvas and paint. It was less, maybe less about trying to create this window on the world, like we do in the Old Master paintings and more about experimenting and thinking about emotions and the aesthetic ideas that you can express through the formal elements of art.

It's just a very different way of thinking about painting and art. But I think a very, eye-opening way to reapproach art. So it's interesting. I can see why there was some pushback, right? Because it was new and different.

Glen Nelson: Yeah, I mean, I think our Church has, has had a different opinion of abstraction than other churches. So, at the same time that President Kimball was saying we needed our, you know, we need our own Michelangelo's and so forth, [00:34:00] the Pope was saying to modern artists, don't abandon us. We need you. And so it was, it was a call for artists who are writing, who are creating work and contemporary styles to come together and contribute to what the messaging of, of the Catholic church would to be. And they put their money behind it. They opened a museum almost immediately at the Vatican. And now it's the second largest museum in the Vatican. It has all of the, of the big names of the 20th century. There's Picasso. There's, you know, like just goes down the whole list. So they've really supported their artists. And I think one aspect of it that's compelling to me is the, is the possibility that abstraction can communicate things that are impossible to articulate the unknowability of God and power that's much easier in a way with abstraction than it is with, let's say illustration [00:35:00] or styles that are completely realistic.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, beautiful. Thanks. That's a really good point. So I also Glen, I liked that you brought up landscape a few minutes ago, because as I read through these 3 chapters, I felt that this might be a really nice way to sort of highlight the stylistic differences that you're each focusing on in each chapter.

So I wanted to look at a landscape piece from each chapter. Linda, we'll go to you. And, I mean, these are so iconic, the harvest scenes, the kind of wheat fields. Lorus Pratt has a beautiful one. You talk about this a little bit in your chapter. How are these landscapes more than just pretty pictures of the geography? What, what are the, the symbolism or the ideas that they're trying to express through these landscapes?

Linda Gibbs: This is my opinion, my personal opinion. Anyway, hard to look at any work of art without trying to look deeper into [00:36:00] layers of meaning. And when I look at the landscapes of the harvest, I can't extricate the fact from them that Utahns were committed to hard work to turning, you know, to making the desert into a rose and to making it productive.

And so there is this overlay of the style of the Impressionist style, I should say American Impressionist style, which is a little more structured and less, kind of a fleeting moment than you see in French impressionists. So you get the perpendicular lines in, Edwin Evans and Lorus Pratt’s grainfields that lead us, lead our eye into the landscape. But then, so you have the style, but then you have, again, what is it telling us about what's important to these artists? Yes, they painted the [00:37:00] mountains. What did the mountains symbolize? I don't think I have any examples in the, in the chapter of their mountainscapes, there's that whole, you know, holiness to the Lord in, in, all of the landscape and they couldn't divest from the actual landscape.

I think their religiosity, their belief, and this does go back in American landscape painting to the very beginning in the Hudson River School where they saw God in every leaf and every detail. I think that translates into Utah landscape painting.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I, I see that too. That sense of finding God or even a kind of divine Eden-like place in the landscape. And you mentioned, too, the idea of, especially in these early days, the sense of reclaiming the land, right? There was definitely this narrative in the 19th century among the settlers, and you saw that it was a [00:38:00] desert, that they had to work hard to reclaim the land through the providence of God and make it blossom as a rose.

I, and I like how you point that out, that that's part of the symbolism that you see in these landscape works.

Linda Gibbs: Of course, there's no sense of the other occupants that were there before.

Jenny Champoux: Yes.

Linda Gibbs: The irony, you know, but that's history. That's just the history. This is our land and we're going to make it what we need to make it into. But it was there. I think it's, you can't diminish the fact that Utah their land, their landscape as, you know, as their refuge, and where they had to build the place that was safe from persecution, and so that adds yet another layer of importance to the very ground that they're standing on.

This is where we can worship as we please, without fear for our lives, and, know, that's a pretty heavy mantel to lay on the [00:39:00] ground.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. And thanks for bringing that point up. Because it is important to pay attention to who is not in the art, right? Who doesn't show up and the indigenous people that were there, that were part of that geography. But again, like you said, the, the early saints had a specific history and a, a narrative that, and a sense of, I think their, their duty to, to, to reclaim this land and build Zion there.

So it's complicated for sure. Yeah.

Linda Gibbs: So I think it is an important point to say, what did what does this art leave out? And that's a whole other subject for another time, but they were highly selective as all are all artists are and what they choose to focus on and what they did choose to focus on is very telling in terms of the society.

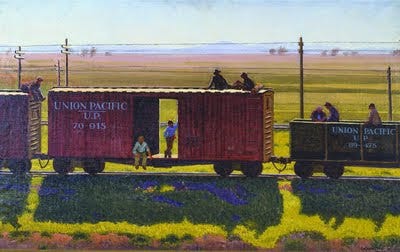

Jenny Champoux: And then Glen, in your chapter on the Art Students League, [00:40:00] you talk about an interesting painting by LeConte Stewart, um, called Private Car. This is from 1937. Can you talk us through this painting a little bit, and, and how it compares to those earlier harvest landscapes that Linda was just mentioning?

Glen Nelson: Well, I love Linda's examination of the potential connection to Monet and the Haystack series. I was always curious to know about the Paris art missionaries in the questions of influence. So I found that one a really interesting paragraph or two, Linda. For me, LeConte Stewart's Private Car is is his most exceptional painting and Wallace Stegner, who is the famous writer and also one of his colleagues at the University of Utah said it was probably the finest picture ever painted by a Utahn or in Utah and unlike its competition.

He said it totally resists the temptation to sensationalize the Utah scenery. So I think that scenery is all well and [00:41:00] good, but the artists who have something to say about it are the ones that capture my attention the most. So when Mabel Frazer is doing a landscape, she's playing around with it. The colors, for example, might be very different. And LeConte Stewart's, this story is basically during the depression. And Utah was really hit hard by the depression. People don't realize how, how difficult it was, in part, because they wanted to avoid taking any money from the government and they suffered for it. But in 1937, this was going on and people were riding the rails and the statistics of the number of people in America who were riding the rails is a really, really big number. So this is landscape. That's quite beautiful. And then there are Union Pacific trains going through the landscape with people riding on top of it or in open cars, and so that's their private car, which isn't as fancy as that title would suggest, as they're trying to find work someplace else.

Jenny Champoux: So, I, I love that you talked about this. LeConte Stewart is my cousin. [00:42:00] Well, he was my grandmother's cousin, so I, I like, I have a family connection. I never, I mean, I never knew him, but I, so I've looked at a lot of LeConte Stewart's art and I also love, he has many pen and ink sketches of Utah landscapes. And as much as I love his beautiful paintings, I also, there's something, that really appeals to me about the immediacy of his pen and ink sketches of little, little rustic Utah scenes, you know, maybe a barn and a horse and a tree, that's just kind of, I think it shows a real love for the people and the landscape, that he's just capturing these little vignettes of things and, and elevating them, these sort of quotidian, everyday, moments you might see on a farm, but elevating them to something that is a beautiful art form.

I love that about him.

Glen Nelson: Well, you [00:43:00] know, I'm not a, I'm not a Stewart scholar. But from what I've read, this guy was constantly drawing. Every single day after work, he would try to go find some barn or, or whatever. For me, the works that have the most impact are those that have a melancholy tone to them. Like a Hopperesque feel to them. Kind of depopulated. Or the lighting is such that you're saying, Wait a minute, this is, this is a little sadder. And part of it when I'm, I don't know if this is fair to give a biographical reading to it, but by the time he was 16, both of his parents and all of his siblings had died. I mean, he was a loner. And then he finally met his wife when he was doing the murals for the Hawaii temple. And I think his life ended up kind of nicely and he, he has a successful and satisfying life. But there is this loneliness inherent in his work earlier on that I really find beautiful and it's it's different than just going out into a landscape and just painting what you [00:44:00] see. He was always trying to figure out how he could manipulate the things he was seeing. Like, if I move that tree over a little bit, what would happen? What would happen to the composition? And he was he was a scholar of color theory and other things too. So there's a lot more going on than just setting up an easel on the side of the road for him.

Jenny Champoux: For sure. Yeah. Okay. And then our third landscape, I want to talk about the one you already mentioned, George Dibble, Cedar Breaks No. Two. This is from 1952. And if you're listening to us, I hope you'll go to the show notes or buy a copy of the book and make sure that you're able to compare these three landscape paintings because they're each so different, but so intriguing in their own way.

So tell us about Cedar Breaks No. 2.

Glen Nelson: Well, he was teaching, Dibble was teaching at whatever the name of the school was at the time, BAC. In my era, it was SUSC, now it's SUU,

Jenny Champoux: Okay.

Glen Nelson: He was just [00:45:00] really intrigued by the natural landscape there, which is a, a really beautiful place. You know, cedar breaks is this really fascinating thing. It's just this sheer, sheer cliff with almost nothing growing below it.

And it's just very dramatic. And so he thought like a good cubist would, what if I reduced all of these things to its simplest form and because he's a watercolorist, that's essentially a single stroke. And the thing about watercolor is, you know, If, if you make the stroke and don't like it, that's, that's pretty much all you can do.

Like you can't erase it, I guess, you can't paint over it really readily. And so this was from, what was it? 1952, this watercolor. And immediately he said, I've landed on something. And when I look at the image now, it evokes my experience there more than a photograph would. And, this guy was a smart guy and he knew how to change the smallest thing, the white space on the corner of [00:46:00] a, of a artwork, what does that do to your eye to let you pace yourself to see it? And how is that? How is he leading your eye in the painting? I, and so I really think he's swell. When we're talking about him as this rabble rousing modernist, he's not at all. Like this is many, many years after other artists are doing similar things in New York, like let's say Milton Avery, for example, or, or John Marin, who was an influence. So it's not that he was, it's not that he was radical. He was just responding to his training and his development and, you know, evolution as an artist. But he was doing it in an atmosphere wasn't particularly welcoming. But there were enough of a group of people who got what he was doing that he felt supported though, I would think.

And as you talk to his family members, all of them are amazing. And quite a few of them connected to the arts now, different, different [00:47:00] artistic disciplines. They really talk with pride about George. You know, he

Jenny Champoux: Yeah,

Glen Nelson: he stood up for himself. He made work that was meaningful to himself, but there's another story for him.

He sold a work to the Utah to the unit to would it be the state of Utah itself. Another LDS artist was in charge of the collection at one point and said he was going to go clean it quote unquote and he took sandpaper to it and just and pretty much destroyed it. The museum the the state collection to their credit have kept it and when they exhibit it they note what happened to it exactly and so he was offered Dibble was offered to replace it or whatever and he said no that’s the work now. You did it. You keep it. So that was, that's, that was a little combative maybe, but I, I think justified. And so actually we put that [00:48:00] image in the book as well. So, those are, you know, it's, it's the state, it's the Church, it's other artists, they're all, they're all struggling with this and he was sometimes a focus of their displeasure.

Jenny Champoux: yeah. I, I liked that. Glen, you ended this essay on Dibble with a reflection on whether, you know, Do we still see that same kind of opposition to artistic change today? And so let me ask you both and Linda, I'll start with you. How would you answer that question? Do you see evidence of openness to stylistic difference in our Latter-day Saint culture?

Linda Gibbs: Well, I'm a little removed from it. I mean, I'm a lot removed from it, so it's a harder for me to say. It's certainly, there was certainly resistance when I was working for the church. People took things so literally. I [00:49:00] remember one time I was carrying, of all things, a Harry Anderson painting.

I think it was, it had angels in it, flowing robes and somebody was offended by the fact that the robes like wings, you know, so was, you know, I was just blown away by how limited people's vision could be that they could even be offended by something that wasn't even there, but in their mind implied. I know that the Church has made advances since then. I don't think it's come far enough. I think as Glen mentioned, I think there still is an anti-abstraction definitely. And for the reasons he named, I absolutely agree. And that we are brought up in the Church to equate art with something that is easily [00:50:00] translatable.

And, and we have a bias against, there's a bias against the individualist that comes with being an artist. I remember Arnold Friberg saying to me once that the beehive state is called such because it's a working, the working beehive. Everyone contributes and artists don't fit that symbol because they're out, they're outsiders, they work alone. And so there's this built in discrimination in a sense, if you get too highly individualized. And I think that is something that modernism in the Church is, is still combating.

Jenny Champoux: Fascinating. Glen, what about you? Do you see encouragement of newness in the art?

Glen Nelson: I do. I have a really interesting vantage point because I've worked with this, of reaching out for artists who in [00:51:00] some way identify with the Church all over the world for a few decades now, and I have a database of a few thousand names and they're all, you know, it's, it's, it's wild. They're doing fascinating stuff, completely distinct one from the other, for the last, you know, safely to say 25 years or so, I've had an email from somebody somewhere in the world every day, saying, Hey, here I am. Hello. and the most common comment they make to me is, I feel so isolated. And that's the guy this week who was writing to me from Zimbabwe and also somebody who's in Provo, you know? So I think that a lot of artists though, it's not, it's not endemic to our culture. A lot of artists don't quite feel understood. But I think that it's, it's hard, it's hard to break through. I suspect that social media platforms are helping with the democratization [00:52:00] of expectation regarding art. I think almost every phone is a little art collection. A lot of people have a lot of art on their phones. The young people in particular that I know are happy to show me, Hey, look whose work I'm just following now.

This is so cool or whatever. And I don't think that they're hoping that their work looks like somebody else. The opposite. Yeah. So I, I think that's a good thing and a healthy thing and the people at the Church itself, I wouldn't say at the temple necessarily this is happening, but at museums and the institutions that are affiliated with the Church, we've had some very well educated, ambitious, progressive people in charge for a few decades now who are trying to push the needle when that wherever they can. And I, I've seen quite a lot of progress. So I was on a jury once for the Church History Museum [00:53:00] international show. And there was, there was a lot of controversial work in the sense that it was abstract or it was, you know, video art or installation art or whatever. The Church acquired all of it. Bought all of it, and they've exhibited it. And so I think that people like to project onto the Church, quote unquote, whatever that means their feelings about it. And so those who are looking for some kind of ax to grind will blame the church for its inability to do this thing or that thing, which may or may not be true. But from, for me, what I'm seeing is a different side of it. Having worked just recently with the Church for the last five years on this huge exhibition of 120 works at the Church History Museum show right now, are much more willing to show interesting things and be, and talk about it in bold ways than most people give them credit for.

Jenny Champoux: Oh, I'm, I'm really glad to hear that. And, [00:54:00] I loved the show by the way. Fantastic. It was such a joy to get to see all those artworks gathered together out there. And I'm glad you brought up the International Art Competitions because for almost 40 years now, the Church runs those every three years. And that really has been, I think a good impetus to help Church leaders and also just viewers think about a broader definition of art. We talked with, Laura Paulsen Howe in the first episode about how as soon as they started that competition in the 1980s, they realized they were going to have to include tapa cloth and basket weaving and, you know, things that they hadn't really considered high art.

And it's not just the materials, but also as you pointed out, the style, right? That abstraction is often the traditional style in in other cultures, and it's it's not for us. It's not for as Americans or sort [00:55:00] of the Western art tradition. We tend to be more figurative typically, but abstraction is traditional for other cultures.

And so it's it's been, I think, a good way to have a broader perspective and to rethink some of the assumptions we tend to make about art.

Glen Nelson: If I can say one additional thing about that,

Jenny Champoux: Please.

Glen Nelson: that show is super important in the discovery of new voices. So it's a themed show, so they they'll announce the theme, which is usually a scripture, and then everybody has to send work that in some way connects to that, which is not how artists tend to create work. They're kind of shoehorning sometimes their work into this theme. So I wouldn't even say that artists, let's say, outside the US are sending their best work to that show. They're sending work that the, the Church they imagined will like. But, but what I do every single time there's a show is I, I capture all of [00:56:00] those names and then I hunt them down and say, okay, what else are you making?

So let's say in Jorge Cocco, you know, when he first started sending works to the Church History Museum and they became really quite popular and are beautiful. Actually, his work before that's really interesting. The cubist work, the sculptural work, the graphic design work and the, uh, and the etchings work. All of those things are really cool. Like they're, they're legit. I don't think we've even now seen those works. So it's, it's not a double edged sword. It's just an incomplete story. The international competitions are great. And I would say the same thing about Springville, those Springville shows that they have and multiple shows each year, but let's say the spirituality show that they do, that is the most incredible thing. These open calls for huge shows and artists who aren't necessarily, you know, involved in art for paying their [00:57:00] rent still can have this wonderful way to communicate. Which I think is really, really cool. Don't you think that's cool? Like, I don't know. It's amazing

Jenny Champoux: Yes. Yes. Yes. Absolutely. Yeah. There are really exciting things happening right now. Thank you. Okay. I am ending every episode by asking our guests to each describe a Latter-day Saint artwork that is personally meaningful to them, for whatever reason. Linda, let's go back to you.

Linda Gibbs: I think I would choose one that's in the chapter. You can show it. It's John Hafen's Girl Among the Hollyhocks. I think it's, I had an experience when I first moved to New York and I had dinner with some friends who were acquainted with some very prominent, collectors of American Impressionism. In fact, since they, they both passed away, they have donated their collection to the National Gallery in Washington and the Met.

That's the quality of their collection. And I followed it up with presenting them with a [00:58:00] catalog of, that I did for Harvesting the Light all those years ago. And they wrote to me and said that, that painting was good enough to be in any major collection of American Impressionism. And so it speaks to the quality that our artists were producing in the late 19th century, early, it was, I think 1901, speaks to the quality of it.

It's a personal painting. It's his daughter in their backyard. It's just has come to stand for me as as the highest quality that LDS artists are capable of achieving and in any methodology.

Jenny Champoux: And I love the Utah connection there with the hollyhocks that were so popular with the settlers there. Yeah. Wonderful. Thank you. That is an iconic piece in our heritage. Glen, how about you?

Glen Nelson: Well, I want to say [00:59:00] ditto. I love that painting so much. Linda, where is that painting now?

Linda Gibbs: Well, I'm not 100 percent sure. I had to lobby to get it out of President Kimball's secretary's office to put in the show. He did not want to let it go. And so I placated him at the time with getting a nice giclee copy. And, it went into the exhibit and then it was on permanent exhibition at the Church Museum.

I have heard through the grapevine that it has gone back into somebody's office. I don't know. I don't know what, where it is, to be honest. It needs to be where it can be seen by everyone.

Glen Nelson: I think my apartment would be an excellent place.

Linda Gibbs: I know where you can get a nice print.

Glen Nelson: I don't. I don't do those. Thanks.

Linda Gibbs: I know. Me either.

Jenny Champoux: Okay. Glen.

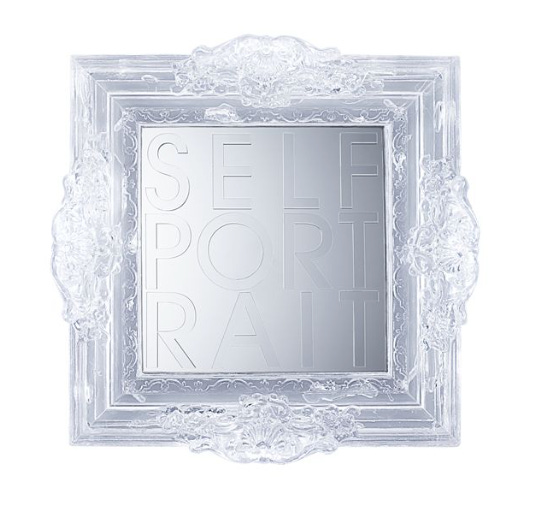

Glen Nelson: [01:00:00] Well, a very different stylistic choice. But when I first moved to New York, I lived with Ultra Violet and she was one of Andy Warhol's factory people. And she had joined the Church in the mid-eighties and I liked her work a lot. It was pop influence, but it had a big spiritual. And, each year I would go, she would, she would twice a year, she would say, hey, come down to my gallery. And my, you know, where my studio rather come down to my studio in Chelsea. And so I would go and I would see new work and she was always doing something cool. And I said, oh, I would love to acquire something. And she was, oh, you can just have it, but not today. She would say, anyway, so years and years past doing this, and she was getting older. And I just felt this real urgency. I don't know what it was. It felt like a spiritual thing, a real urgency that I needed to acquire some of her work and she wasn't responding. She would always push me off. So I had a friend who used to be at Sotheby's and he's a dealer and he's [01:01:00] LDS as well. And so he connected with her and she ended up selling me three works. So my favorite work is called Self portrait. It has a really long Baroque title. I have no idea what it means, essentially, if I could describe it, she had an antique, she's French. Her family's, uh, kind of aristocratic French, they were glove makers and they came from money, anyway.

So there's this ornate frame that she had cast in some way that she could reproduce it with resins. So the image itself, if I'm just like, since it's a self portrait, it's a mirror and then acrylic frame, but it's really an ornate frame. Then with little letters that are also mirrored, it says self portrait. And so, uh, that was her self portrait when I asked her what it was, you know, what her most favorite interpretation of it was, she would say, oh, it's the way that anybody can anybody. You don't have to be rich. You can just [01:02:00] look in a mirror and you can, you know, you can have your own self portrait. So what it means to me, though, and my family was, it sat in a very prominent place, actually, just right behind me here. And we looked at it every day and we, you know, adjusted our ties and we, and for me, it meant if Oscar Wild-like, my face is a reflection of who I am, then I'm creating my own self portrait every day in the way that I'm taking care of myself or the way that I'm showing emotion or, you know, whatever. And so for me, that work had a conceptual side that I really like. Something that's not illustration that anybody who came into my house could immediately understand and love. A personal connection because she was very dear to me, it was sad to me when she passed away. Anyway, so that [01:03:00] was, that was my connection.

We had a collection that was kind of large for a small apartment in New York, maybe 150 works of LDS artists. And all the people that we've discussed today, were, although they were like little prints or little drawings, but all of those people and a lot of contemporary work was in that collection.

And actually the Church History Museum acquired it, the whole thing. I was feeling at the time, uh, what should we do with all of this artwork? And I just, again, felt this urgency to do something with it. And so they acquired it all. So that work is at, is somewhere in that building somewhere.

Jenny Champoux: Wow. That is so fun. I, I hadn't heard of that work before and I love hearing your personal interaction with the artwork over years, uh, and, and with the artist too. That makes it so nice that you had that personal relationship.

Glen. Linda. This has been fascinating. Thank you so much for joining us [01:04:00] today.

Linda Gibbs: Thank you for having us.

Glen Nelson: Thank you so much.

Jenny Champoux: I'm grateful to you both for all the great work you're doing to preserve and study Latter-day Saint art. Thank you.

To our listeners out there, thanks for listening in. I hope you'll join us next time as we think about ways Latter-day Saint artists have considered geography, culture, and landscape. Heather Belnap will teach us about the international travels of Latter-day Saint women artists in the early 20th century. And James Swensen will discuss how Utah artists used photography to define a Mormon landscape. And also, Rebecca Janzen will consider the confluence of Mexican culture and American norms in the visual culture of Saints in Mexico.

So we'll see you then.

Thank you for listening to Latter-day Saint Art, a Wayfare Magazine limited series podcast. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. [01:05:00] I hope you'll order a copy of the book to read the full essays and see all the gorgeous full color images of the artwork.

You can learn more about the book and other projects at the Center's website at centerforlatterdaysaintarts.org. If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to listen to the other episodes in this series. You can subscribe to Wayfare Magazine at wayfaremagazine.org. Thanks to our sponsor, Faith Matters, an organization that promotes an expansive view of the Restored Gospel.

And if you'd like to learn more about Latter-day Saint art, check out my other podcast called, Behold: Conversations on Book of Mormon Art. You can also learn more at my website, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. With more than 10,000 artworks, it's the largest public digital database of Latter-day Saint art. You can search by scripture reference, topic, artist, country, year, and more. We recently added a new section for art based on Church history, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. The website is bookofmormonartcatalog.org. That's bookofmormonartcatalog.org. Check it out and see what exciting new art you can find to enrich your study!