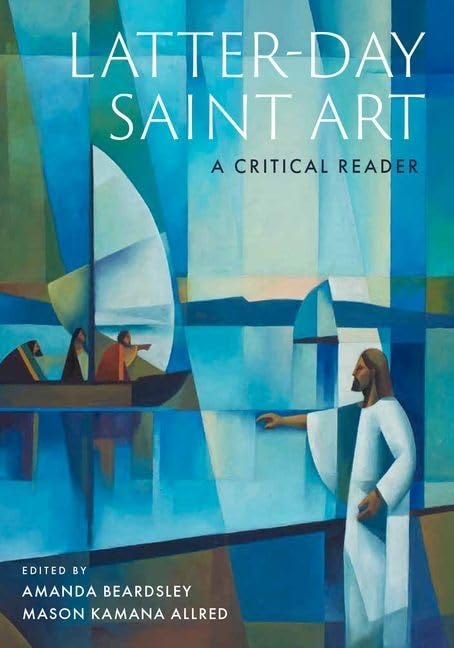

Jenny Champoux: Welcome back to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux in Latter-day Saint Art, I'll guide you through an examination of the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. A video and transcript of each episode along with images of the artworks discussed are posted at Wayfaremagazine.org.

In today's episode, we'll look at the history of films in the Latter-day Saint tradition. We'll focus on four themes: approaches to embodiment, the performance of values and beliefs, the influence of global cultures, and the projection of a Latter-day Saint self-image. Our guests today are Mason Kamana Allred and Randy Astle.

Mason Allred is an associate professor of communication, media and culture at Brigham Young [00:01:00] University Hawaii. He earned his PhD from the University of California Berkeley with a designated emphasis in film studies. He is the author of Weimar Cinema: Embodiment and Historicity and Seeing Things: Technologies of Vision and the Making of Mormonism. In addition to being a co-editor of Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, he wrote a chapter for the book titled, “The Piety of Perspective: Bodies, Media and Cinematic Experience In Latter-day Saint Film, 1970 to 2020.”

Randy Astle is the author of Mormon Cinema: Origins to 1952 and over 60 articles on Mormon film. He has taught Mormon cinema at BYU, acquired hundreds of DVDs as the BYU Library’s Mormon film specialist. He edited special issues of BYU Studies and Mormon Artist Magazine. He served for two [00:02:00] years as film editor for Irreantum and programmed film screenings at the Sunstone Summer Symposium. And he created the Annual Academic Forum at the LDS Film Festival. He's currently writing a second book, Mormon Cinema: 1953 to 2024. His chapter we're looking at today is called, “Moving Pictures: Subjectivity and Mormon Identity in Documentary Film.”

It's going to be fun to hear from these excellent scholars and to turn our attention to a slightly different form of art today. So, let's get started.

Mason and Randy, thank you for talking with us today!

Mason Kamana Allred: Happy to,

Randy Astle: Thanks for having us.

Mason Kamana Allred: be with you.

Jenny Champoux: Mason, will you tell us more about your work as co-editor of this book? What was your vision for this project and how do you hope it will inspire future scholarship?

Mason Kamana Allred: Thank you for that question. I love this book, so I'm happy to talk about it. And it was so much work it's really nice and [00:03:00] almost cathartic to talk about it now. But to be honest, the, the project was already really in place with, with Laura Hurtado and Glen Nelson kind of planning it out and reaching out to different authors who could cover uh, subject areas of expertise. So, by the time I was brought in to not only be a chapter, uh, author, but to be a co-editor with Amanda Beardsley, was already kind of set. So that was nice. She had done a lot of that front loading, preliminary work. But then when I came in, 'cause she's had other things going on in her life, she had to turn her attention too.

So, Amanda Beardsley and I came in and took over editing together and worked with Glen Nelson and Mykal and all the team at the Center and Richard Bushman. And what it was like was, um, because we already had the author set and the, the basic subjects, we could still kind of mold a little bit like the direction of chapters and the overall sense of the volume. And we really enjoyed that. And, and Randy knows this too, but like, we kind of agreed, uh, Amanda, I, and, and Glen too, that we really wanted to have, [00:04:00] um, we wanted to be quite academic. We wanted it to like work in a college classroom, you know, at any, any campus, whether it was like BYU or Harvard, that you could totally use this in some class on, on religion and media or religious history or, or art and religion, something like that. So, we did want that, that kind of register to hit that register. Not to be inaccessible or pedantic, but to, to be legit. Like we wanted to treat it like that, and we felt like we had the right authors to pull that off.

The other thing we both felt strongly that like we didn't, as much as possible, we didn't want people to write about art in a way that you could do if you'd never seen the artwork. So, we wanted them to do a lot of, to kinda lean into formal analysis, close textual analysis whenever possible. And that was great 'cause some people were more comfortable with that than others. Um, but you saw even historians kind of getting into more of that to really get descriptive and interpret at least analytical, if not interpretive, uh, at some points on these.

So, we did want more of that. We knew we were gonna have tons of images. [00:05:00] So we had like, you know, 200 and something images in there. That was a lot of work. I'd never really worked with that many permissions and images and files before. That was daunting. Um, but that was the basic idea and we didn't wanna really tell authors what to do far as like their approach or coverage.

And we tried to let them know like, it doesn't need to be exhaustive. Like that would be ridiculous to pretend like we could be comprehensive what we can. But you go where it takes you. And we tried to give them as much room to just do what they do 'cause they're all brilliant. Um, and I think it worked out well because of that. The, the sad thing for me was. I love this project, but the sad thing was when we first all signed up, and Randy will remember this in like 2020, it was like this idea that we were gonna get together like once, twice a year and have these big kind of like, know, moments to really counsel together, think about chapters, share with each other, what you're working on. And that only happened over Zoom, which was helpful, but not quite the same. So that was kind of sad 'cause I really wanted to hang out with all these people and we [00:06:00] gotta do like Zoom breakout rooms instead, but do anything about it at the time, right? So that's kind of how it all came together. So, it's been really exciting, uh, you know, steep learning curve. It's been great for me, but, um, I'm really proud of it. It's really a great volume. In fact, let me do my Bushman gif and hug this book because, uh, it, I'm really proud of it.

I think it's a really great book. I can't wait to see how people build on it and how they critique it and do new things, but I feel, I feel really great about it.

Jenny Champoux: Thank you. Yeah. And I'm glad you held up the book there for people to see. It is a gorgeous cover with that Jorge Cocco artwork on the front. Um, and I, I like, I appreciate that you, and, and also in our conversations with Glen Nelson and Amanda Beardsley, each of you have talked about how this was not an exhaustive survey of Latter-day Saint art, but, um, just sort of a first step and I think there's so much great information here, but it also just reveals the breadth of what [00:07:00] there is that can still be tackled in this field and how much there is to think about and analyze and contextualize. So, I think it's really inspiring for future work too.

Mason, let me ask you one more follow up question. How did you decide the order of chapters? Because I noticed you and Randy have the only two chapters that deal exclusively with film studies, but they're, you know, separated by four or 500 pages in the book. What was your thinking as you put the chapters together?

Mason Kamana Allred: So, we, we first looked at them kind, basically chronologically first. That was the list we had and how authors were reached out to. So, we all kind of saw it like that. And then as a, we got closer and closer once they were kind of written and we'd had seen versions, and I were just talking about it and we're like, it, it actually might be more productive.

It just, 'cause, I don't know if it's just the way we, you know, learned about history in grad school and stuff, but just we thought it'd be more productive to get more kind of, um, constellations of ideas [00:08:00] across time rather than just this chronological. There's always a sense, I think, with chronological histories that it fills too inevitable it feels like you're headed towards some end goal. And, while that might, that might work well, theologically, I don't think it works great to think about art history that way. So, we thought it would be really productive to just bring things together and see if there weren't some kind of guiding themes or topics that we could cluster them around. And that was really productive for us too, because then we both sat down separately and thought about how we might do that, then came together and merged some those ideas and adjusted those.

And, um, so yeah, we ended up the way it is, which is within a cluster. They are chronological, but they're smashed together in, in ways that we thought would, um, open up new ways of thinking about the chapters themselves. they, so they work like that across the volume. So, I think just because, um, the way that Randy and I each approached ours, um, it didn't make sense in the way we were doing that to put them together.

And so, his worked out so well to put with, and I'm already kinda getting into this chapter a bit here, [00:09:00] but because he was thinking about, is such a great idea, let me just glaze this chapter for a second to think about how Latter-day Saints are so steeped in this idea of record keeping. I mean, you have like early scriptures in the Church and the Doctrine and Covenants saying keep a record like the Lord is telling them, keep a record. And there's like keep journals, keep records. such a great way to think about it is kind of the practice of Mormonism record keeping and as bearing testimony. You know, those are two things you've heard over and over across, um, since 1830 up till now. And so, to think about documentary nonfiction film in those ways works so well because then we could put his together with Colleen McDannell and Terryl Givens who both think about kind of like theological ways of thinking that are shaping what's being made and what's being displayed and how we're thinking about art.

Randy Astle: That's interesting how they connect because it is because otherwise it is kind of a jump between their subject matters and mine, all of a sudden we're talking about documentaries, where'd this come from? But, but because I went so broad, I don't think I spent more than two or maybe three [00:10:00] paragraphs on a individual film.

But Mason, you were able to, to limit your scope and go much deeper in your formal analysis of the films that you talk about, uh, in a way that, um, would, that I didn't do in my chapter and that. I don't think any of the films that you discuss have ever had a serious critical analysis, um, from the Mormon scholarship angle about them.

Oliviera’s films were completely unknown until they've just been restored at, at BYU's film archives. And, and so you're like the first one to introduce this to the, the film scholarship community, which is, um, a different approach from mine that really phenomenal way to, to really get into the depth of, of the symbolism and the meaning and everything that was going on in these films from these directors that most Latter-day Saint viewers and readers will not have heard of before.

Mason Kamana Allred: And I don't know if you know this Jenny, but like the way this worked out is because we were kind [00:11:00] of covid lockdown, I was doing research trying to find these films and I was interested in like what else is out there that I just don't know about. So, Randy's right that several of the ones I chose to go deep on are actually pretty obscure in the sense of if you're thinking of Mormon cinema. And that was a kind of deliberate move I made. So, then I felt like if you're gonna do that, to be fair, you need to be really descriptive and spend more time on each one to really, 'cause they may never see these.

And the Oliviera ones, José María Oliveira, like, know, I'd heard these but I'd never even seen it back then when I was writing it.

So, I was reaching out, trying to find people online who had a copy. And so eventually I, I get his phone number and I talk to him on the phone and. And then I,

Randy Astle: Nice.

Mason Kamana Allred: Ben Harry over at uh, BYU Provo, 'cause we worked together at the Church History Library. I was like, Hey, you gotta go to his house and get these masters and like restore this thing.

And he was like, oh wait, who's it? So, in that conversation, I got Ben to go over there and meet with them and he got, and he actually had, and only Oliviera had them in his garage. Then those got restored and it was this really great relationship where like [00:12:00] I was teaching this Mormon cinema class then the next year it came around again, I had a restored copy, like a digital file of the restored copy from

Randy Astle: Huh.

Mason Kamana Allred: because of that. So, and then there was a Salt Lake Tribune article

Randy Astle: I didn't know that's how it happened.

Mason Kamana Allred: like what, just a few days ago talking to him

Randy Astle: Yeah,

Mason Kamana Allred: Right. So was really happy about that and, um, not that I'm trying to like, you know, get everyone exposure to these movies. Never heard of alone, just for the sake of being obscure. But because I think they're really worth looking at and talking about, like, I do think that they merit more attention.

Jenny Champoux: I really liked this about both of your chapters that you both showed that there is a much longer historic tradition of film in the Latter-day Saint tradition that isn't as well known. Um, and I think both of you mentioned kind of the one, when people think about Latter-day Saint cinema, the first thing they think of is the movie God's Army from 2000. Randy, I saw you recently wrote a little essay [00:13:00] about this in the Association for Mormon Letters journal. Uh, so tell us what I mean, this, this may be a film that most of our listeners actually are familiar with, as you pointed out, one of the most, you know, groundbreaking LDS films.

So, what, what was so revolutionary about this film? Um, what effect did it have?

Randy Astle: Yeah. Well, um, I wrote this, uh, blog post, um, a couple weeks ago because God's Army actually came out on March 10th, uh, 2000. And so, I'd been casting around with some AML people or, or Ben at BYU and just saying, Hey, is anyone going to do anything, um, to, to celebrate this? And so I thought I'd write up a quick little, um, in memoriam or celebration of, of this film on its 25th anniversary, um, be, which is ironic because I kind of feel like I've made a, a little vocational career here for the past 25 [00:14:00] years of proving that God's Army was not the first LDS or Mormon film.

Uh, when it came out. I, um, was really impressed by it, which is, I'll talk about that in a, in a minute, but I, I guess I have enough of a nerdy or academic bent that I thought, you know, I know this is not the first movie. I showed movies to people on my mission. I'd seen Legacy at the Legacy Theater, uh, and there's this mysterious Brigham Young movie from 1977.

So, I thought, okay, what else can I go out there and, and see that there is, and you know, so that's taken 25 years as I've been learning all these thousands, not just hundreds of films that came before God's Army, um, let alone the explosion that it caused. So, so God's Army is not the first, um, LDS or Mormon film, Richard Dutcher's, not the father of, of Mormon cinema in that way.

But we, I do have to give it credit, which is what I was trying [00:15:00] to do with this little blog post, because it did change everything. It's very arguably the most important, um, Mormon film ever made, at least in terms of the corpus of Mormon cinema and, and what it did to shape the course of that movement. Um, so I was a, I was a freshly enrolled, newly minted BYU film student in 2000 when it came out.

And there were occasional student films and things that, that talked about something happening at BYU. So those were technically, uh, informed by the Church or the culture. Um, but then these rumors started going amongst the, the film students about this film that someone, some guy in California made a feature film about missionaries and he's going to release it.

And no one knew who he was, uh, at least in my peer group or anything like that. But then he came for a Tuesday or a Thursday afternoon, um, college devotional there in the Harris Fine Arts Center. And he showed the trailer, and it was just the, I was [00:16:00] talking with Ben Harry about this 'cause we're the same age.

He was there with me and he remembered it as well. Similarly, that the feeling in the room was just electrified. And there were, I think, two people crying and asking questions like, how did you do this? What, you know, where did this come from? What changed, I think, with God's Army was that it made it legitimate to tell, um, Mormon stories, but outside of, of a church setting.

Not like literally going to work for the Church or showing things in, in Sunday school or seminary or firesides, but to put it into a commercial theater where it's accessible to the entire world. And, and before God's Army, you didn't think that way. That, that you could do that, that that was even a possibility.

And after God's Army it was, uh, from that point on, you, um, could legitimately make a feature film about a Mormon or an LDS subject matter, which [00:17:00] just seemed unfathomable, didn't even occur to us, um, for the most part, uh, before that. Um, but, uh, you, you get sub genres. You, you get different, um, perspectives from people in different geographical locations.

And it took a long time, but more and more women filmmakers, uh, entered the, the fray. So, it, it was slowly expanding, um, what it meant to, to be Mormon cinema, um, or the perspectives that you got from it. Um, but I don't think any of those would've happened, at least not on the timescale that they did, if, if God's Army hadn't come out, um, when it did and had the effect of just saying, yes, now you can actually, um, make these films for a general audience.

Jenny Champoux: After I read your essay, um, I, I went back and, and watched it.

Randy Astle: Oh.

Jenny Champoux: Uh, and boy, it really was, I think, ahead of its time. And like you said, the [00:18:00] way that it shows these universal human experiences of with family trauma and relationships and finding spirituality, figuring out who you wanna be in life, finding love, um, finding how you want to relate to the world.

And, but it's, they, the characters happen to be Mormon missionaries. Um, but it really centers around these, these bigger human universal themes and, um, I think really, really lovely. Yeah.

Randy Astle: Yeah, I, I should watch it again and, and see how it's held, um, held up because I haven't really talked about the film itself. It's a well-made film, well-written, well-acted, um, shot, music, performances, everything. Um, it'll probably seem a little dated with the no smartphones and things like that, but, um, if it hadn't been one of the better Mormon films made, it wouldn't have had that effect. It would've, um, well had the opposite. In fact, it would've [00:19:00] tanked the idea for another 10 or 20 years, which is what's happened in the past with the, the movie from 1977 Brigham, which I've alluded to. I like it. I think it's fun, but it is a little campy. And it did kind of kill Mormon cinema for another 20 years in a, in a way.

Mason Kamana Allred: you know what's

Randy Astle: Um, just because it didn't have the, didn't have the effect.

Mason Kamana Allred: I was gonna say on, on God's Army, I think Randy's right, and, and he's written about it before where he talks about how like it's nice 'cause he has this smart way of thinking about it off that line. And like, well, Elder, you're not in Kansas anymore. It's a shift, right?

You're you're not in your old Mormons anymore. And I remember I went on my mission in 2000, so I watched it right before I went on my mission. I was like, whoa, this is what I'm getting into. Wow. Because I'd seen like Labor of Love, I'd seen like some of these missionary ones where it's just so soft and sweet. then I saw that and it really opened my eyes. But I remember I was in Las Vegas and I do remember members in the ward like, oh, that's like disrespectful. That's, you know what I mean? It was a

Randy Astle: Hmm.

Mason Kamana Allred: reception of it, which tells me it did do something. It, it did shift the needle a little bit. And if it's ruffling,[00:20:00]

Randy Astle: Yeah.

Mason Kamana Allred: is probably a good sign. But I will say this too, I teach it in that Mormon cinema course, and it's wild how much these students who've never heard of it, never seen it. Love it.

Randy Astle: Really?

Mason Kamana Allred: it's often their favorite movie of Mormon cinema. And so, and they, the, and

Randy Astle: Huh?

Mason Kamana Allred: missionary is always like, oh yeah, that feels pretty spot on to my experience.

I'm like, that's crazy. 25 years later. connect with these audiences still, uh, these latter

Randy Astle: Yeah.

Mason Kamana Allred: who've served missions. So, I'll just say it still seems to work. It still seems to hold up. The music feels a little bit outdated, I think, to a lot of students. Um, but the way it's cut together, the topics, it covers the of the characters.

Like I, I think it's still a good movie.

Randy Astle: It's interesting, uh, in that they relate to it so much because as I'm writing my, my second book, the second half of the history of Mormon film, um, when you're looking at it historically, the first thing you think about with God's Army is the theatrical feature film. Now we are having these movies, [00:21:00] The Other Side of Heaven, Brigham City, et cetera, et cetera, showing in theaters.

But the more I thought about it, the more it was that point that you just made, Mason, that it was more realistic than Labor of Love, a Church missionary film or any other movie that missionaries had been in made by the Church. Um, so I'm calling the period, it's like mainstream realism more than, than, um, theatrical feature films because.

God's Army shows a mission experience in a way that no film before it had, but which is accurate, which is realistic and, and which is some of the people were very offended by the shenanigans. They take a picture of a missionary using the toilet, things like that. Like yeah. But that's, that's how it happened.

And then some other people, there were people in my student ward at BYU who were offended because they showed baptism some blessings and these things that are sacred ordinances, um, which they didn't think should belong in a commercial theater. It was not a, a [00:22:00] sacralized space that was a appropriate place to have these kinds of things.

But that was Richard's entire argument. Yes, it should be. Why are we not sharing this with people? And I've written about that before about other small cultures who have similar reactions. Um, when they see something from their nationality or their religion, um, being portrayed on screen, they're like, you're, you're an insider sharing this protected thing with outsiders. That's a violation of the community boundaries.

Mason Kamana Allred: I just say before we leave God's Army, that there is something redeeming, I think too, about its form. Like it is, it's an indie film, and so it feels kind of scrappy. And I think that's a great way to think about a, a Mormon mission too. The way it's cut together, the way it's shot, it feels like not cheap, but you know, it's on a budget.

You know, it's an independent filmmaker making it, they're not gonna like license huge needle drop songs and stuff like that. Um, and I think that scrappiness works in its favor. know what I mean? Instead of saying like, oh, it's a [00:23:00] simple little small production. It works well to take like this idea of a mission as a microcosm of life and the Latter-day Saint stuff through it.

So, I, I think it holds up maybe because of that too. It, it works. I.

Randy Astle: Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: Okay. So reading your two chapters together, I saw kind of four main themes running through, running through them. So, I wanna kind of organize our discussion around these. The first one is this idea of embodiment that you both touch on. And in our Latter-day Saint theology, we have this duality where we believe the body is a God-given gift, and it's, it's, uh, one reason that we come to the earth and it's, it's a wonderful thing. On the other hand, it has this potential to be dangerous, um, or, um, arousing and right, and that we have this idea that you have to control the body and its passions and appetites. Um, so Mason, why don't we start with you and let's talk a little bit about how you see filmmakers in [00:24:00] the Latter-day Saint tradition exploring these ideas of embodiment or the body.

Mason Kamana Allred: Well, yeah, thank you. It's, you know, I think that my mind started to think about the movies like this because, so like in graduate school I studied with Linda Williams and she's really the one who originally kind of like coined this phrase of body genres, the type of genres that are really trying to appeal to your body over your mind. That's changed over time. Right. And you look at a lot of like, kind of like art house horror and stuff, it's doing it differently, but still the idea remains. And it was a, a new kind of rubric to throw them through to think about how these Mormon films are working. And, and it drove my attention to certain ones over other ones. So, it was a kind of guiding way to think about them. And, and you're exactly right. Like the way I saw it was embodiment is so integral to Latter-day Saint theology it's almost weird how much they, um, love and believe in flesh and bone and that it will be eternal. And they believe in like a Heavenly Father and a Heavenly Mother who have flesh and bone. So you really wanna know how to like live in [00:25:00] this and it will be glorified. I mean, that's kind of wild and kind of amazing to believe, things like that. How's that showing up in your cinema then? And it's just, um, easy to see in a, in a lot of Mormon cinema fare. Like that they're very comfortable with kind of, I think kind of schmaltzy, sentimental.

Let's get the audience to cry. And if you're having a spiritual experience, excellent. Who am I to judge? You know what I mean? But like, if you are kind of dropping into these melodramatic forms to, in a negative way, manipulate in a positive way, uplift or get them to feel something audience, I think that's actually pretty normal.

And Latter-day Saint creators have gotten pretty good at doing that, but it's also safe. So, you're making what I, I think in terms of the culture or kind of harmless entertainment, it's okay to cry or it's okay to laugh, right? Like as Randy said, after the kind of this new birth of new Mormon cinema in the early two thousands, like, you know, you get a lot of comedies. Um, and so that seems fine, right? To get a, to use bodies on screen, to get bodies in the [00:26:00] audience to cry or to laugh seems okay as, as long as it's appropriate. Things that they're crying or laughing about. What's really scary for Latter-day Saints is these things when you drip more into like horror or eroticism or these kinds of things that are gonna pull on the body in different ways, like you said.

So, um, to really freak you out, to get you scared, to jump scare, like your stomach to turn. These kinds of things, which can be used so effectively to engage with really important ideas. But initially, I think Latter-day Saints are scared of it. It feels wrong. We're not supposed to do this. Why are you doing this?

And then of course, with arousal, anything that's gonna be like intimacy on screen, which is again, if you think about the theology, these are people who I think on paper, believe deeply about the importance of intimacy between humans and procreation. And, and sex is like actually a really important thing, think they believe goes on in some form eternally.

So it's interesting that the, that the practice, the way it's showing up in movies is all that. Like avoid all that. [00:27:00] So once you think about it like that, it seems pretty clear. It's not too like, you know, this crazy, weird academic way of thinking. It's just like, how are bodies being addressed through these films and what techniques are they using to do it? So instead of looking at those mainstream ones I'm talking about that are getting you to cry, I was kind of interested in ones that make you feel other things and how they're addressing your body. So, then I turned to these, know, seemingly obscure ones in some ways, especially ones that were from other countries to think about like how, how do they pull this off? How do they get you to feel and what do they want you to feel and why do they seem less timid about some of these topics? And surely some of that's their culture, right? If you're coming from Spain or the Philippines, it's a little bit different than a Mormon corridor sense of like, let's just call it like prudishness. And so that, I just got really fascinated by it and I found individual scenes that are doing it in really interesting ways and to what to me was so encouraging was like they seem quite sophisticated. Whether it was conscious and deliberate or it's just the way they make movies based on their brain, how it works [00:28:00] and their culture, where they come from. I was really impressed with the way that they would edit, shoot, sound, design, all this stuff address your body, to feel certain things that I felt like were, not just manipulative for the sake of getting an audience to cry, but to get you to sort of identify with certain characters that I think would make you think new thoughts and maybe even question

Randy Astle: Hmm.

Mason Kamana Allred: that I thought were really actually quite creative and productive.

So, I kind of wanted to praise that and point it out, but it's a kind of just a way of thinking about Mormon cinema-making in terms of bodies on screen and bodies and audiences. What does that tell us if we look at it like that?

Jenny Champoux: Right. I, I really liked that one of the, um, kind of tropes that you point to, that shows up repeatedly in the Latter-day Saint cinema is, um, dancing. That, that dancing pulls these two things together where, um, it's like, can be an expression of beauty and like self-actualization, but it can also be [00:29:00] potentially like being overrun by the body's passions. Um, and even, I mean like Napoleon Dynamite, right? Like you give that example, the, the dancing scene is that sort of climax where he, um, lets himself go and is able to do the, perform this dance and it's like the highlight of the film and it's sort of where he finds himself right through the dance. But then you talk about how in these 1970s films from other countries, dancing was also, um, a really important symbol that the filmmakers were using to express some of these ideas. Can you tell us a little more about that?

Mason Kamana Allred: So, once I was focused on like the way the body's being used, um, symbolically in films to get at the audience, then I was thinking like this, like you said, where dance is kind of like media. For Mormons where it can be so great and it can quickly be so scary, right? So, like, yeah, it's a sign that you're finally in touch with your body and maybe you're feeling feeling great and you're dancing.

It's a wonderful thing. [00:30:00] Please dance. Like Brigham Young would say dance. But then maybe, uhoh, it's this like weird sensual dance you shouldn't be doing, you're losing yourself. Something like that. And media's always like that too, right? Like we, oh, we love it. We're gonna use it. And Latter-day Saints are so good at using media and content creation, and we're early adopters, but media will corrupt you.

It's dangerous, it's scary. Don't let it come into your home. So that ambivalence around it, the duality of, of dancing and media showed up for me in, in these films. So I wanted to focus on that. And you're right, it's happening in so many where it can be a sign of, of either. And if you go back to the one in the early seventies, like Eros, uh, The Dead, the Devil and the Flesh, that scene, it's almost like it just reaches out the film and grabs you and is like, you've gotta talk about me.

'cause it's so unexpected. It's so,

Randy Astle: weird.

Mason Kamana Allred: so weird. It's so beautiful. Can we describe it for your listeners? I can't play, I can't play it in the background. I guess I could have set up, share my screen and do it, but

Randy Astle: We have video, so you can just stand up and.

Mason Kamana Allred: lemme just act it out and get the song going.

First of all, the soundtrack is amazing. [00:31:00] He has an original score for this film that's just beautiful and you have to understand in by the early seventies, late sixties, early seventies in Spain, we're talking about Spain at this time, and this is the first like Stake President there, convert to the Church, but wanted to be a filmmaker. And if you look at the other films around that time, it's just so fascinating the context in which he's making this. 'cause you know, they're coming towards the end of Franco, Spain, they have a dictator, right? Franco's running things quite oppressively. So, a lot of like control and censorship, even in filmmaking and so forth towards more like nationalism and religion and family and stuff like that. You start to have these early things creeping in of like a little bit of horror, a little bit of eroticism, the exact things I'm talking about coming in the late sixties, early seventies. When he makes his, he's interested in these topics, but he is not quite doing it the same way as everyone around him. Um, so in his scene of dancing, it's in the spirit world and Korihor basically invites or commands these spirits to stand up and dance, kinda like in the way you used to when you had a body. So they're like enacting what it would be [00:32:00] like to have a body 'cause they miss these, these lustful, sensual things that were so like carnal when they had a body. So this dance ensues where it's semi-choreographed definitely from the beginning, but then they're not all in unison, great song. It's just shot and fascinating ways where he'll, like, blocks it so he can see the whole thing in a long shot, but he'll get a lot of like the waist down kind of a shot.

So it's like a, you know, medium closeup, but the bottom half of the body to the top half. And I'm like, this is visually exactly what I'm talking about is if you shoot a movie to address someone's body, not their brain, he's doing it formally in the way he's actually making the movie. So you're visually taking in what some of these people are doing on a editing level, formal level, so they have characters doing what they're hoping to do to your body anyway, in that sense, it's this weird, thing that they don't have bodies to experience this, but they're trying to remember what it felt like and go through these hollow movements and these kinds of things. And I just, I think, I mean, like Randy said, it is weird. Like I said, it does stand out, but [00:33:00] it's also and emotionally like a beautiful way to do this. To actually think about what he means by the doctrine of being in a spirit world and losing a body and how much Mormons love the idea of getting a body back, but to then act it out as a dance where you miss having a body and you're missing the point what it means to a body. Like that's actually quite sophisticated and I think it's worth that scene.

As weird as it is, I kinda like that it's quirky and weird too. 'cause you will never forget it. But it's doing something I think on a few layers.

Randy Astle: Yeah, the, the mise en scene, the whole way that he shot it and staged it. 'cause from that point on, there's no dialogue for this scene. It's just the dancing scene with the music. And, but it's uncomfortable. It's not just weird. It's, um, it's uncanny, Freud's heimlich, where you have these bodies imitating something alive, but we know they're not alive in that way.

And he's doing this with actual actors instead of like, um, stop motion puppetry or things like that. Um, like when you see a [00:34:00] doll over across the room, you, and at first you think that's a real person, you're like, oh, you're, it freaks you out for a second. Oliviera manages to sustain that across the scene by making them act, they're moving like puppets.

They're moving unnaturally. And so this thing which should be joyful or physical embodied distinctly feels off in, in that way, uncanny and, and strange. And that's his the greatest scene in the film for the tragedy that it would be to, to lose your body and to not be able to perform these very physical actions.

And I think it, it's standing in for sex and for other things that you wouldn't want to, um, to portray. I, I like that you brought up another dance scene in the 1990s cult film, uh, Plan 10 from Outer Space by Trent Harris, because these are aliens, not zombies, but they're moving the same way, um, in this really awkwardly choreographed scene, which is such a contrast to, to how Napoleon Dynamite, just lets go with, with the physicality.

[00:35:00] And, and that's more of an eruption of, of abundance and pleasure and joy, uh, as opposed to, to when it's done in, in this false way that just doesn't, doesn't feel right. Um, I think that Mormonism, um, focuses in the culture often about what is wrong with these movies? What, what content is in a film that makes it R-rated or that makes it objectionable?

Is there sexuality? Is there violence? Is there profanity? Those are all legitimate concerns if, if you don't want to participate or view that kind of behavior. But it can make you kind of restricted or uptight about anything that gets close to, to physicality in, in that way. And so it's great when a film like Napoleon Dynamite can say, well, set aside your, um, uh, restrictions about what you're going to be able to allow yourself, your body to do and, and just enjoy this moment of, of abundance where, [00:36:00] um, all the repression kind of gets broken through and you have this great moment of joy or, or something like that.

You, you don't see that very often in LDS films. Uh, done really well. Um, that's maybe one example. Um, I. The, there's a, the climax of Once I Was a Beehive, uh, is a crying scene, but it's so, it's very physical and emotional in that way, but it's a scene where this teenage girl who has been repressing her grief over the death of her father for the whole film, finally lets it out.

And, and you just have this surge of, of abundance as film scholars sometimes like to say, where everything just, all the emotion comes through the physicality and it works really well in, in these, in these rare occasions when it happens.

Mason Kamana Allred: I think the other thing that's so interesting about the dancing too, 'cause, and I'm reminded when Randy was talking about the scene from The Dead, the Devil, and the Flesh, is because it also gets at this idea of like, like are you in control? Are you being controlled? [00:37:00] And that even takes us back to Heretic and Randy's essay on this, the blog.

But,

Randy Astle: Oh yeah.

Mason Kamana Allred: that's important for ritual movements because like in The Dead, the Devil, and the Flesh, Korihor kind of commands them up and it's shot like he's a puppet master and they're being sort of controlled to do this dance where it's always this, that kind of low angle up at him and there's a literal, uh, art frame behind his head, like a painting.

So it frames his head, he tells 'em kind of what to do, and then you shoot from a high angle over them, this kind of wide shot to see the whole thing. And then they dance. And then you come in with those closeups I was talking about. So it, it's edited the feel like he's kind of controlling them and they are hollow mindlessly just doing what they've been told to just dance like this. That can happen in film. So like, are you following into the unison uniformity of just like someone else is controlling you? And you could say that about ritual too. Like if you've ever done like a Hosanna shout or how some people take the sacrament, or even in the temple when you do rituals where everyone falls into unison, it can feel so and ritual and you're being controlled.

You're just like a cult that mimics each other [00:38:00] or it can feel like you truly are feeling something. You’re an individual in this collective doing something amazing. And that's gonna depend on the way you do it, where your head space is, all these things. But true that, that that little flip of the coin. Is a fascinating way to think about all these things. Media, dancing, control, they're all that duality. And I think dancing scenes just get at that so well of like, are you truly letting loose, like Napoleon Dynamite or are you actually kind of controlled? You're doing the same Fortnite dances, everybody else does, and but manipulating controlled by short form media and video games.

You know what I mean? Like that's a really important thing to think about.

Randy Astle: Well, when I was reading your chapter again, Mason, um, I, for some reason I kept thinking about Richard Dutcher again, in, in this context, because of all the Mormon or post-Mormon directors. Uh, the way he approaches physicality is really interesting. We talked about it a bit with God's Army. Um, but the main, his character, Pops, has epilepsy, I [00:39:00] believe.

He has seizures and, and he heals through a blessing someone who they're teaching who's crippled and got beat up and, and so they give him a blessing. And then the next day, um, it was like this transformative moment for him. Um, so, um, like the elephant man not laying, going down to bed on his pillows, Pops, decides not to take his medicine that night and he dies the next day.

Uh, and so this is all a very physical thing. And then in Brigham City there's violence 'cause it's about a serial killer in a small Utah town, and it gets, um, a bit of gore and, and a lot of dread. Um, there's sex in States of Grace, his next film and, um, also violence as well, gang violence. But then you get to his, his first film that came out after he left the church falling, which he said he thought of at the same time as God's Army.

These are all in his, in his approach to Mormonism. That film Falling is about, uh, he plays a, um, [00:40:00] freelance cameraman in Los Angeles who follows around, um, violent crimes, gang shootings, car accidents, things like that. And he films 'em for the news and, and the violence there gets very gory and, and just uncomfortable in the same way of these dances that we're talking about because he's, he's putting the, the, um, gore right in your face.

But it's, it's not to celebrate at all. It's very uncomfortable. And, and it shows how tragic and, and horrific this is. And then even when there's a sexual scene in the same film where his character's wife has to undress during a film audition. It is not sexual. It's uncomfortable in the same way as the shootings and the stabbings and things like that because it's showing, it's exploited, that she's being exploited, um, by the people in power in this, um, film situation.

And, and it's a brilliant way to just, um, show how horrific some this misuse of bodies or mistreating other people's bodies, um, can [00:41:00] be. So I think that Dutcher needs more credit for that kind of, uh, really visceral filmmaking.

Mason Kamana Allred: He needs to unvault that film. 'cause none of us have seen it. But it's, it's the Night Crawler. It's like the night crawler one. Right. Where they, he feels like

Randy Astle: Yeah. It's the one that he, he actually filed a suit against Night Crawler against saying that they had copied his idea. I only saw it because he's a great guy and he let me see it at his studio.

Mason Kamana Allred: But I think that's, like Jenny and, and as we move on here, like when you think about creating art and Latter-day Saints creating film, I think it's important to remember as creators that even like, kinda the way Randy's talking about that movie from Dutcher right now is that any scene of violence or any scene of sexuality, a commentary on that thing. It doesn't necessarily mean it's already saying do this, you know? But it is usually a way of thinking about that. And so it's important to learn how to, to appreciate and attend to the framing how it's set up in the film as far as narrative, but also even just formally the way it's shot.

What is the, is the music telling you? It's just like Randy just said, like he knew how to watch that movie. Right? [00:42:00] But if I just read online, it has

Randy Astle: Yeah.

Mason Kamana Allred: this, this. I'm gonna say, oh, man.

Randy Astle: Oh yeah. People are really offended by the, the blurb about that movie. Um, 'cause they haven't seen it. Um, and see that it's not praising this kind of stuff. Yeah.

Mason Kamana Allred: I’m not saying that Latter-day Saint film needs to get gorier or needs to be more erotic, but I am saying that I think we should be sophisticated enough, and I would hope for the kind of art that really thinks deeply about how to treat these things, but that violence and sex and sadness and crying are three of the most universal things for all humans.

So how do they get, how do they look when you take 'em through the filter of Latter-day Saint theology and thought, I just think it could be done in really sophisticated ways, and it has sometimes, but I think that, um, you'll see even more and more in that direction.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, really interesting. So for me, I am much more comfortable looking at like a painting or a sculpture or a drawing. Um, that's sort of my training and film [00:43:00] studies feels a little different to me. It's a different medium. Um, I mean, just the way that there's, there's movement, there's character development. Things happen and change in a way that they don't in a static painting. Right? And, um, so I, I wanted to, let me ask you first, Randy, ask you, um, how, through, through this kind of performance or action of the characters in the films, is that being used by Latter-day Saint filmmakers to express Latter-day Saint values or beliefs?

Randy Astle: Hmm. Yeah. Um. Uh, somewhat of the, it's not where I started on this article, but the ending where I, I wound up, um, putting my focus is that there's not any universal, um, monolithic kind of Latter-day Saint values or, or, um, things of that nature where, where you can really homogenize and put [00:44:00] people into a box.

Um, so I wound up saying that it's individual. There are as many ways to have, quote unquote Latter-day Saint values as there are people who have passed through, um, the faith. Uh, the, so I, I focused in my chapter about documentary films on three different, um, ways that you could approach this. And, and Mason uh, mentioned it at the beginning with the record keeping and, and the kind of proselytizing.

Um, so one is if you are focusing on proselytizing, if you are trying to put your films out there for outsiders, quote unquote, um, to, to be exposed to the Church or to the faith for the first time. Then what tends to happen is it does tend to homogenize, it does tend to, to gloss over faults and quirks and individualities, uh, to just say like, this is what Mormons are.

So we've had two films from the seventies and from the 2010s called Meet the Mormons, uh, which obviously just by the titles tells you that they're gonna say, this is what our people are like. Um, the first film [00:45:00] from the seventies made by Judge Whitaker or Wetzel Whitaker, the director of the BYU Motion Picture Studio, the first lines of dialogue of, uh, voiceover narration or something like this is a story of a people, uh, people not unlike you, people who are admirable and part of society today, and let's learn about them.

Um, and as soon as you do that, you know, you're, you're not going to be getting, um, into the nitty gritty, uh, the remake by Blair Treu focuses on individuals rather than on like practices, customs, like family home evening or tithing. Uh, but he profiles individuals. So you do get, um, individual, um, personality traits in those, but the effect is still to, um, put your best foot forward sometimes at the expense of, um, realism or, or believability.

If you're just, if you're facing inward, if you are, um, making a record of a person, then you're, you don't have that weight on [00:46:00] you of like, of presenting the church in its best light to this outside audience, which is somewhat that we talked about with God's Army. People being offended that he's putting this out there to, to this outside audience.

Hundreds, thousands of historical documentaries and, and repertorial and other styles. So I, I kind of focused on the ones that are just profiles or portraits of an individual or of a family. Um, so in, in film speak, those would be like cinema verite films or, or direct cinema, observational cinema films where the camera and the subject are just there in a room together.

Um, and those can be brilliant, those can be some of our, our greatest movies, um, where you just get to spend 20 or 60 or even 90 minutes with someone and, and to see what their life is like. And that's what, um, you know, myself as someone who's no longer practicing in the church. To me that's the, the beautiful thing about [00:47:00] Mormonism, the, the beauty of these people's lives without having to say this proves a thesis about the Church itself, or its veracity or anything like that, you can still see these beautiful, wonderful people who are living these lives of service and love and, and dealing with their struggles of disabilities or death or, um, relationships. And so, um, that those are the greatest values to me, and the, the greatest ways to express people's faith and how their faith informs their lives. Um, not because of some statement about, um, the Church, but it's just about this is who I am.

And oh, and then the third way, um, that I, I tagged onto the end of my article is about people who feel misrepresented or underrepresented by the large culture of the church, especially near its, its center, um, racial minorities, women, some or um, LGBTQ, uh, people and their allies who have been very prolific and making films advocating [00:48:00] for acceptance and, and, and just making their version of formalism.

Made known, um, in, in contrast to the dominant narrative that, that you normally see.

You've got people with cell phone video functions, um, there's lots of documentation. It's just going on to social media.

They're not making giant finished documentaries or anything of that sort. But when they hike up Y mountain to light the Y in rainbow colors, every phone is going, that kind of thing. And I, I think that's going to have a long-term impact on, on the Church, um, or on the culture I should say, where you've got, um, people's voices being amplified in ways that they couldn't be before the internet, before social media, before, um, smartphones and, and things like that.

I've gone off on a tangent, but hopefully that shows that there's a variety and infinite variety of different ways to express how Mormonism affects people's lives through film. And that's why I think, [00:49:00] um, documentaries are some of our, our greatest films because it's taking its material from real life like that.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. No, that's, that's great. And that's actually one of the other themes that I wanted to touch on is that idea of, um, how maybe Latter-day Saint images and film have changed over time from this more, you know, monolithic, leader-led, you know, institutional, top-down projection to the world to, like you said, more individual members of the Church sharing their own experiences in a variety of ways now that there's so many more platforms to do that as an individual. Mason, let me ask you too, uh, how, how have you seen that evolution? And, um, and also I wanna get your thoughts too, on the second theme of this performance of Mormonism through characters in, in film.

Mason Kamana Allred: Yeah, I think it's true for, for feature films. To that there's been more room more recently to deal with kind of more warts and faults and a little more [00:50:00] three-dimensional characterization for sure. Especially like Randy said, when it's not institutional so people have a little more freedom. Um, but the kind of stuff where it was like a lot of comedies were just kind of making fun of, um, some Mormon culture I don't think accomplished too much.

Their performance of it was kind of already a, a self-caricature, which can be fun and funny, but, um, I feel like that didn't necessarily move the needle artistically as much as many of us would hope. So, the performance of of Mormonism on screen though, in some ways there, it's like, you know, obviously missionaries are huge, this performance of dedication, like literally dedicating time, years of your life to something like this. And if you look at that, that kind of a parameter, films like that where it's like this sense of these people dedicate themselves, they consecrate their life to this, but they're not perfect that I think that has been kind of productive. So, if [00:51:00] that's for an outside audience, which I often think hasn't been enough of that, it's still, to me, to my mind, it feels like a lot of these films still feel somewhat insular.

Like the hope is that the core audience will be Latter-day Saints, who will, who will get this, and then if it reaches others, excellent. I'm, I'm sort of excited about those who would try to flip that model and say, let's try to reach everybody. And if Latter-day Saints get it on an on another level, excellent. But they should reach everybody. I think that's also really, really worthwhile to try and do it like that. The performance though, I would say, like, I think even, like Randy was saying with, with the ordinances in God's Army or, or at the end of Brigham City that he just wrote about, again, with these transcendental endings. Like to, to display Latter-day Saints as those who engage with ordinances that some way literally change their lives, is such a great prospect for cinema because it's literally changed over time. But it's through this catalyst that may be very meaningful to these people. So to show someone, [00:52:00] someone a blessing and then the person walks like that, I, it is so audacious in God's Army to do that.

'cause you're gonna lose half your audience if you have a miracle like that. But to do something like that, or at the end of Brigham City to have that sacrament meeting where they come together and don't take it, then they all take it and it's really, I think, touching communal moment that's cathartic for them.

And maybe even transcendental as, as Randy wrote about it, that's actually a bold move to show the performance of Mormonism as we who do ordinances. That for us have really deep meaning and are embodied actions. Taking bread, touching someone's head, putting oil on 'em, whatever, that actually can change ourselves, change the world. You know what I mean? Like that's, that's a bold way

Randy Astle: Yeah.

Mason Kamana Allred: if you can pull it off.

Randy Astle: I was gonna say that, uh, they're by definition embodied. They, uh, it's not just a, a prayer or a internal revelation as you're reading your scriptures or something like that. You have to pass that tray around in the scene in Brigham City. And every single [00:53:00] person refuses to take the sacrament because the bishop who feels guilty for the people who got killed on his watch, um, doesn't take it.

And then it goes back to him and he takes it. And it means more than, than you normally ever, um, realize if that, if that's a routine part of your weekly life. And then it goes around again and everyone takes it this time. And it, it's an embodied to go back to that previous theme, um, healing moment and knitting together, unifying of this community that's, that's been scarred

Mason Kamana Allred: Yeah.

Randy Astle: by this, um, traumatic event that's happened over the last few weeks.

Mason Kamana Allred: to think about it is like the performance of Mormonism, literally saints is often this connection between the temporal and the spiritual that like it's true. Like you don't believe that he's gonna bless this guy and heal him by just thinking in his head like, you know, father, please bless this.

It doesn't work like that. He actually has to put his hands on his head or put oil on him and his hands on his head, or they have to touch the bread and put it in their mouth and digest it and [00:54:00] pass it around. But it's connected to these spiritual beliefs and hopefully for them spiritual outcomes and that I think we shouldn't lose sight of in Latter-day Saint filmmaking is that connection between the temporal and the spiritual. That embodied actions are connected to like eternal ideas. And if you lean into that in ways that are kind of smart, think that can actually be a really cool cinema.

Randy Astle: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Uh, I was gonna say, I was actually the, a home teacher of the actor who got the blessing in the film when the film came out. So I knew him personally and I knew that he could walk and things like that, but it still had that same effect where I'm like, okay, um, this, it's a miraculous moment.

We've talked about transcendental endings, um, which comes from a, a book from 1972, I think, by the director and screenwriter, Paul Schrader, where he talks about, um, three international directors, auteurs, uh, Yasujiro Ozu, Carl Dryer in Denmark, and, um, Rob Roberta, Robert Brion, and France. [00:55:00] And how they have the, this style where their films are very flat emotionally, um, through the duration and they just pair it down, take away any emotional meaning, um, or psychological motivation for the characters or things like that until the ending when they have this moment, this eruption of abundance, like I mentioned earlier, where something amazing happens, someone comes back to life. Or something like that. Um, and, and those are the kinds of things I, I mean, that that book is now feeling dated and, and people have had a lot of, um, things to say about it and, and Schrader's own filmmaking practice.

Um, but his, his film from a few years ago, First Reformed, had an ending like that where, um, this, uh, suicidal pastor instead of killing himself has this lengthy embrace with this woman. Um, it's not very sexual, but it's very emotional and, and, um, I want more of that in moron films, I

Mason Kamana Allred: [00:56:00] Yeah,

Randy Astle: guess.

Mason Kamana Allred: First Reformed was awesome, but you know, this style, he's

Randy Astle: Yeah.

Mason Kamana Allred: this, at least the way that, that, uh, Schrader talks about that transcendental style a, as a form to use is so interesting. 'cause it, it would today work like, um, so narratively for film, it would almost be the parallel to like a, a, like a digital detox because what you do with the audience is you bring the stimulation down so you get a kind of like baseline that's much lower than a normal film.

So that then when you do have it, it works better. And if you believe in a theology of opposition in all things, you need the sort of silence. So, the sound means something, right? You need the sort of that lower baseline. So, the eruption is bigger and grander. And, and I'm glad that, that Randy brought that in in his discussion of, of, um, Heretic and Brigham City. It's a great, like, just think about making movies like this where you can use all of these tools at your disposal. You’re not reinventing the wheel. It's actually already there. But you're thinking about why use that one and what it might do. And when it's done well, man, it can be powerful.

Jenny Champoux: Okay, fourth theme, [00:57:00] and we've touched on this a little bit already, um, and this may apply mostly to, to Mason's chapter, but maybe both of you. Um, the fourth theme is the way filmmakers are bringing their own cultures from around the world into Latter-day Saint, um, based ideas in film. And, you know, this is a theme that popped up throughout the book in the different chapters, and, and on these podcast episodes too. And I think that's really important think about the ways that we are a global church, and, um, right, that there's more than one way to think about how to visualize Latter-day Saint ideas.

It's not, doesn't have to be just an American or Western type of visualization, but, um. Uh, Mason, do you, do you see, I mean, you talked a little bit about Oliviera using his sort of Spanish culture. Can you give us a little more detail about how he's bringing those two things together?

Mason Kamana Allred: like it'd be really helpful if [00:58:00] you look at trailers from the early seventies of like The Blind Dead or other series like this that have these elements and that little micro genre in, in Spain at the time is called Fantaterror. 'cause fantasy with terror. So kind of horror with fantasy. But these Fantaterror films, you know, they feel a little bit campy. But they're starting to play with these scary things. And so in, in The Blind Dead, for instance, these like Knights Templar or zombies who come back, so it's the undead Knights Templar, and they're supposed to symbolically represent that old conservative regime of Franco that's still holding people back from progressing forward.

So politically people are writing about at the time, like they kind of know this new cinema that's eking through the cracks is exploring more eroticism and horror because it's like been so repressed under Franco that how can we push back a little bit cinema. So you think about, um, Oliviera as the Stake President there in Spain making this movie in that context. And he'll, he'll gesture towards some of those aesthetics. [00:59:00] But because he is doing it in such a Mormon way, like it's all about this theology of a guy who's like converted to Christianity. He never says Latter-day Saint or anything in it, but this guy's converted to Christianity and his wife isn't happy about that, and she sleeps like with just about every guy that comes into the movie.

Um, so she's cheating on him and he's wants to, he's converted so he's changed his life then when they end up in the spirit world, she is killed. So she ends up there and then he somehow magically walks across a cemetery and he is, finds himself in the spirit world so they can then converse there and, and, and deal with that.

So he has this doctrine of kind of idea of spirit world, how that works. And one moment in the spirit world, they go in a room and there's two Latter-day Saint missionaries with their name badges on. He's infused these ideas about like agency. Uh, he calls one of the guys his good, helping him, Alma, the bad guy, Korihor, like he has definitely infused it with these things. If you didn't know Latter-day Saint doctrine, you might not catch all those, obviously. And it played as like a double feature [01:00:00] with, with, uh, Bruce Lee's, uh, Enter the Dragon in Spain at the time. Like, and it, it's in, you know, mainstream theaters is like a normal movie.

So it's just such a cool, uh, thing that he created there. But it, it is definitely a very Spanish for him at the time, early seventies version of thinking through Latter-day Saint ideas. And, you know, he even says that he was very inspired by films like Exorcism, stuff like that. He is like, how would, how would Latter-day Saints think about the next life though?

So he is interested in spiritualism and life after death and with this belief system of Latter-day Saints, how it show up.

So I just got really fascinated in, in the ways that the culture was, shaping their experience of Mormonism differently, where I feel like they latched more onto the doctrines that they were fascinated by. But then it gets dressed with their own culture, which is I think really great for viewers to see the difference there. 'cause I mean, I've showed like the Singles Ward in my class students from like, you know, Japan or like Tonga. Like I don't, I don't get this, what the heck is this? This makes no sense. So like, they don't quite get the [01:01:00] same culture. So to see the different dressing on the different packaging I think is really good for our brains to see that it can be thought of differently.

Randy Astle: Well the Singles Ward gets a lot of flack, um, precisely for this. Like it's unintelligible if you're from, as far as 40 miles outside of Utah Valley. But I love it for that specificity because in that, you know, 'cause I lived in Utah Valley, I was a BYU student when that came out, like, okay, this is, I get it, it's not going to speak to someone from California, let alone from Japan or Tonga.

Um, but it got to show our culture, a little slice of life culture in 2002 there, um, in a funny way. And I got all the references. It was cool. Um, but if, if Kurt Hale, the director of that film, can do that for Provo. Then what can Leino Baka or someone from, from the Philippines or um, any other director from any other, um, place on Earth would be able to do with a fiction film, but with nonfiction [01:02:00] early in the fifth wave in this post God's Army period, I was really looking at the potential of online video on BYU TV's broad broadcasting range and things like that.

And, and envisioning this period when people would be kind of sending films around or posting 'em all online and we'd have this nonfiction, um, renaissance of what are Church members doing in France? What are they doing here? And everyone's just kind of building a global community that way. I don't think it really happened, um, in that sense that I was kind of, uh, hoping it might.

Jenny Champoux: Hmm. Okay, I am ending every episode in this series by asking our guests to share an artwork that is meaningful to them.

Randy, why don't we start with you?

Randy Astle: I haven't chosen one beforehand because I know what we talked about. Um, I think we haven't talked about New York Doll.

Jenny Champoux: Right.

Randy Astle: much. Um, which is, uh, I, this is a spoiler. I'm working on a list [01:03:00] of my 100 greatest Mormon films for Irreantum, the AML journal, and that's got a lock on number one. So it's a documentary, um, came out in 2005, 20 years ago.

Um, is Greg Whiteley his first film? He's now a pretty celebrated documentarian. Um, it was just about his friend Arthur Kane, who used to be Arthur Killer Kane, when he was the bass player for the New York Dolls, the glam rock punk band in, uh, the 1980s. Um, his life took a turn, took a tumble when the band fell apart, and, and, um, he was dealing with addiction issues and health issues.

And he saw reader's guide ad for the Church and he converted and started working at the Family History Center by the LA Temple. And that's how Greg Whitely knew him. They were friends in the same word, I believe. But then, um, Morrissey, um, in London wanted to have a reunion [01:04:00] for, for the band. And so Arthur Kane, who'd left this whole life behind, suddenly has an opportunity to go back to make up with, um, David Johansson, who just passed away a month ago or so, and his other band mates, um, and play his music again.

And so it's this swirling, um, vortex of a film. Um, Arthur knows that he's living these two completely incompatible lives where he, he has lived them. And what he now has to do is put them together, go back, play his music, be in that environment at the Royal Festival Hall in London, um, see all these people from all these bands.

Um, the Smiths, the Pretenders, uh, um. And, and be there with his old self without losing his identity as a disciple of Jesus Christ. And as someone who's reformed and has this great love for the Church and for Joseph Smith. And so it's just a fascinating film to watch this successfully happen. And [01:05:00] then a powerhouse of an ending, which, um, isn't exactly transcendental but kind of somewhat is, um, which I guess I won't spoil because I think everyone should go watch it.

Um, that it ends with David Johansen singing “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief” over the closing credits, which is a great decision. 'cause we go out on this really emotional song, which has a lot of, um, uh, allusions for Mormon viewers who are in the know. It's a song. It's about Jesus Christ. And it's coming from things like Isaiah 53, how he was a man of sorrow, acquainted with grief.

But we also associate it with Carthage and the martyrdom of Joseph Smith. And so we associate it with him. And now, um, David Johansson is singing it about Arthur, it seems. So you've got Jesus and, and Joseph Smith and Arthur Kane all mixed together with this really resonant and rich, um, symbolism and, and meaning.

So [01:06:00] it, it achieves that kind of emotional peak with no dialogue or anything. It's just a song being sung. But, um, that's the kind of thing you can do in, in a film that you can't do in a painting or a sculpture or a static piece of art.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Thank you. All right, Mason.

Mason Kamana Allred: I was trying to think about this and I didn't choose a painting. Sorry. We're gonna be different, but I'm gonna give you a few and then I'm gonna land on my favorite film. I consider these pieces of art that are Latter-day Saint in some way. So I really love, I'm calling this art, Bushman's, Rough Stone Rolling.

I know it's historical book, but it's, it's an art. And Panic! at the Disco’s “This is Gospel.” Killers’ human song. I mean, we talk about are we dancer, are we human on your knees praying. I think that's important. Um, so I would take those all as somehow Latter-day Saint in some way. And I really like those.

But, um, the film I would choose I, I think I still always go back to Electrik Children as my favorite, uh, you know, narrative feature film. And, um,

Randy Astle: I second that. For [01:07:00] what it's worth.

Mason Kamana Allred: it's a great movie, right?

Randy Astle: Yeah.

Mason Kamana Allred: I feel like this one's really well done. Rebecca Thomas made it after she was out at Columbia, I think she went to BYU Provo for film, but then ending to Columbia got funding and put this movie together. And it's a smart way to approach it. What I like about it is she starts with Julia Garner as this young woman named Rachel in a clearly like fundamentalist Mormon, uh, society in southern Utah. um, so it allows her to do it, I think is deal with very just generally Mormon anxieties ideas, but put 'em in a kind of extreme form because she went with this more like, um, uh, this more fundamentalist, uh, structure around it. And so I like the idea that it's this, um, really like a visual director. I really like Rebecca Thomas's style. It opens with Rachel having a interview with who we find out is her stepfather, who's also like her, the prophet figure that runs this commune here and then her brother there in the room, and they're gonna, and they turn on a tape record, [01:08:00] record. The interview, the interview questions will sound very familiar to most Latter-day Saints. And this, this little girl is just, you know, kind of joking at first and falling into this of power in the room and is shot like that. Like this guy's got all the power. He interviews you and capturing that, that kind of vulnerable situation for a young woman to be interviewed by this man and, uh, just have another guy in there as a witness to, it is a great opening to the movie to already set the stakes of who's in power and who's not. Anyway, she shortly ends up getting fascinated by that cassette player. She, out of her, uh, her room at night and goes down and finds it and plays this, you know, this little tinny pop song of, um, “Hanging on the Telephone” and she listens to it and then she thinks it made her, it impregnated her. So she's gonna deal with this pregnancy.

And anyway, the way it works out to deal with the kind of young woman's experience of in religion, her escaping fundamentalist Mormon setup. 'cause her mom helps her and gives her the keys somehow more understanding. Helps her get a pregnancy test. Actually the film like, kind of follows her experience as a kind of a maybe [01:09:00] unreliable narrator.

Can we trust her that this was an immaculate conception? Is it actually abuse what happened here? And then she'll move, she'll travel from southern Utah, this very deserty escaping into Las Vegas full of lights. She's like on Fremont Street and stuff. And she'll hang out with, um. She gets in this little group of these kind of like punk skater kids. They're in this music scene and different world for her. Um, and try to make sense of, um, what happened with that tape and where's the, where's the father? I'm looking for the father of my child.

And anyway, the way it plays with his anxieties that I was very interested in around media, the power of media, the idea of dancing. She's dancing to that tape recorder when she thinks that she's pregnant. The ideas of, um, religion and its power and the abuses of that power, the idea of a woman's experience in in religion, it's shot well, and even the little touches where I, I can, I feel like I can trust the director. She, there's a little hint of maybe how this happened when. Rachel puts on these red heart glasses that if you know her from Lolita, Stanley Kubrick's version of Lolita that he shot with these red heart-shaped sunglasses.

And [01:10:00] then the end, she has this almost homage to the ending of The Graduate, like with Dustin Hoffman, the Mike Nichols movie, where she pulls up in a red convertible where disrupt and stop a wedding and then to run off. And so I just, I like it when I can see directors have seen the right movies they're quoting them in the ways that work for their own movie, not just in hollow reference. I think that's a powerful movie that works really well. I like the way Rebecca Thomas teed that up.

Randy Astle: Yeah, I've described it, I frequently describe it as, as almost a magical realism kind of thing. 'cause of ambiguity you're talking about. Is that an immaculate conception really? And, and by the end of the film I had an opinion about whether it was or not. But, um, it's, it's so cool that you have these kinds of possibilities that go up, take a step outside of, of realism.

The Devil, the Dead and the Flesh does that, and that he walks into the spirit world. Um, there are lots of possibilities for, um, some more flights of fancy [01:11:00] and fantasy. Um, instead of sticking to strict realism all the time, like it often happens in Mormon films. So it's, it, it provides new avenues for us in that way.

Jenny Champoux: Well, you both have really, um, opened my eyes to a whole genre of art that I really didn't know a lot about. And thinking about the ways that Latter-day Saints are making films for themselves and films to project themselves to outsiders and the way other people are making films about Latter-day Saints, it's just, it's really fascinating to see all that happening. Um, so Mason and Randy, thank you both for joining us today.

Randy Astle: Thank you.

Mason Kamana Allred: Thank you for having us. That was really fun.

Jenny Champoux: To our listeners, thanks for tuning in and join us on the next episode as we consider contemporary Latter-day Saint art. Chase Westfall and Maddie Blonquist, who are both museum curators, will be our guests and we'll talk about current trends in the art and offer our [01:12:00] predictions for the future. We'll see you then.

Thank you for listening to Latter-day Saint Art, a Wayfare Magazine limited series podcast. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. I hope you'll order a copy of the book to read the full essays and see all the gorgeous full color images of the artwork.

You can learn more about the book and other projects at the Center's website at centerforlatterdaysaintarts.org. If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to listen to the other episodes in this series. You can subscribe to Wayfare Magazine at Wayfaremagazine.org. And thanks to our sponsor, Faith Matters, an organization that promotes an expansive view of the restored gospel.

If you'd like to learn more about Latter-day Saint art, check out my other podcast, Behold: Conversations on Book of Mormon Art. You can also learn more at my website, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. [01:13:00] With more than 11,000 artworks, it's the largest public digital database of Latter-day Saint art. You can search by scripture reference topic, artist, country, year and more.

And we recently added a new section for art based on Church history, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. The website is bookofmormonartcatalog.org. Check it out and see what exciting new art you can find to enrich your study.

Jennifer Champoux is the founder and director of the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. She wrote C. C. A. Christensen: A Mormon Visionary (University of Illinois Press, forthcoming) and co-edited Approaching the Tree: Interpreting 1 Nephi 8 (Maxwell Institute, 2023).