Jenny Champoux: Welcome back to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux. Throughout this series, we've been examining the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and talking with contributors to the book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader. It was published in September by Oxford University Press, with support from the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. If you're listening on the podcast, keep in mind that you can find a video transcript and images of the artworks wayfaremagazine.org.

In today's episode, we'll look at contemporary Latter-day Saint art and thinking about current trends. What distinguishing features do we see in contemporary art and how do they relate to those of more traditional art forms? Where is the art headed in the future? We'll also consider the role of the BYU Art Department in shaping Latter-day Saint art approaches.

Our guests today are Chase Westfall and Maddie Blonquist.

Chase Westfall is an artist, educator, curator, and arts administrator. He currently serves as curator and head of gallery at VCU Arts Qatar. In 2024, he served as the interim executive director at the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University. Prior to that, he served as director and curator of student exhibitions and programs at the Anderson, also at VCU. In 2021, he curated Great Awakening: Vision and Synthesis in Latter-day Saint Contemporary Art at the Center Gallery for the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. Westfall received a BFA from the University of Florida and an MFA from the University of Georgia with a concentration in painting. His book chapter we're exploring today is titled, “Toward a Latter-day Saint Contemporary Art.”

[00:02:00] And then Maddie Blonquist works primarily with religious art objects within the BYU Museum of Art’s collection as the Roy and Carol Christensen curator of religious art. In 2018, she graduated from Brigham Young University with degrees in music and interdisciplinary humanities, and she went on to receive an M.A.R. in Visual Arts and Material Culture from Yale Divinity School and Institute of Sacred Music. Maddie has worked at numerous art institutions, most recently at the Yale University Art Gallery and Utah Museum of Contemporary Art. Maddie is not one of the book authors, but I'm delighted that she's agreed to join us to enhance our discussion, offering her perspective as a curator and scholar of Latter-day Saint art.

So, let's get started.

Chase and Maddie, thank you for talking with us today!

Maddie Blonquist: Of course.

Jenny Champoux: Before we jump into [00:03:00] the book, I'm hoping we can tell our listeners a little more about the work you do. Chase, I want to say that you're a triple threat because you're not only a working artist, you're also a scholar of visual culture, and a curator, a museum curator. So, can you tell us how, how do those things overlap for you, or how does your scholarly work inform your artistic production?

Chase Westfall: First of all, yeah, that's a very flattering way to categorize, I think what I do is very kind of you. I often feel a lot of imposter syndrome that because I work in a lot of areas, I'm sort of a quasi or semi, all of those things, with a few other things thrown in. I think, at its best taking that kind of jack of all trades approach creates moments where you can have these really lovely kind of synergies, where the different perspectives can inform one another and augment and sort of be a force multiplier for one another.

I used to play a lot of sort of like punk [00:04:00] rock guitar and I think about like a phase shifter. If anybody has familiarity with that, it's like a, it is a special effects pedal where the different sort of frequencies come in and out of phase. And so, you get these really wonderful, I think, high peaks when the, the different bodies of knowledge can align in exciting ways.

But then you have some sort of troughs and valleys and tough places where you feel like you're not making the progress you might want to, in any given area because of being sort of spread thin. But, you know, so there's challenges that come with not really being a subject expert, not necessarily being an expert in terms of the modalities.

But on the whole, it's a good thing. If you'll indulge me, there's a, there's a term that comes from a really well known curator, which is Ausstellungsmacher, which sounds really pretentious, but it's a German word that just means like “exhibition maker.” And I like using that term because it has, uh, it implies sort of a more pragmatic approach to exhibition making.

And I think within that pragmatic [00:05:00] framework, having all those different areas of knowledge to draw on really helps you kind of get the work done, get projects across the finish line with some assurances that at least it's gonna hit some of the right notes for the different audiences that you're trying to serve.

So anyway, it's a, it's mostly a good thing and, and sometimes a very challenging thing.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I would think that being a practicing artist and having worked with the different kinds of media and materials might give you some additional insights as you're doing scholarly work into analyzing art.

Chase Westfall: I think it does. You know, when you get into, uh, talking through the artwork, which is sometimes the first sort of step in doing that analysis, having some familiarity with the means and methods, I think does help. It gives you an entry point. Or you can engage it as an object, you can engage it as a process in addition to whatever it might sort of mean or [00:06:00] signify.

And bringing that multiple perspectives to bear is, I think, a, a nice way of sometimes triangulating a compelling argument that you want to be able to make for work. I think that's a good point.

Jenny Champoux: Maddie, congratulations on recently joining the BYU Museum of Art as the religious art curator. I'm curious, what are you enjoying most there so far? And is there anything in the role that has surprised you?

Maddie Blonquist: So, I can't say I've been very surprised just because I worked at the MOA as a student for a few years during my undergraduate degree, and they actually gave me quite a bit of independence, and let me work on some really amazing projects at a very high level. And so returning feels very much like coming home. Although it's still surreal to be in the office that, Kenneth Hartvigsen had when he was there and I was being mentored by him, I still sometimes feel a little bit funny opening that door [00:07:00] and I have the key now. But no, it's been really wonderful to, to be back in that space and I'm really enjoying.

Being able to work with the collection and acquire new works into the collection and shape sort of the future of, uh, what holdings we have. And Ashlee Whitaker, who held the role before me, who's featured in this book as well, huge shoes to fill, but I think she's left such an amazing legacy and Dawn Pheysey before her in that same position I'm just trying to build upon and move forward.

So it's been wonderful so far. It's not quite been a year yet, but I plan to be there for a very long time.

Jenny Champoux: Wonderful. I'm so thrilled. And I've known Kenneth for a long time too. We overlapped just a little bit in our graduate program at Boston University and, you know, he did really great work there at the MOA. And Ashlee too, with putting [00:08:00] on some fantastic exhibitions there and did great work. So, I'm so excited that you're part of that legacy now. I'm excited to see what you do there

Maddie Blonquist: Thanks, me too.

Jenny Champoux: As we start thinking about Chase's chapter from the book today, let's first define for our listeners what we mean by contemporary art. Chase, can we start with you? What is contemporary art and how is it different from what we might call modern art or more traditional kind of art of the past?

Chase Westfall: That's a great question. It's an elusive definition. I think anybody in the field would be willing to admit that. Maybe one of the simplest ways to sort of start to signal where it is, is thinking about it almost as, as much to do with attitude and disposition. Certainly more to do with that than, than any particular set of materials or any particular visual sensibility, right?

It's about sort of thinking about art making as a kind of [00:09:00] space of interrogation, as a space for thinking through being vulnerable, asking questions, dealing with uncertainty, et cetera. So I think that marks a big shift in, you know, what we might call like a turn away from like a modernist sensibility towards a post and now meta or whatever you want to call our kind of contemporary moment that, that it's a space for getting murky and kind of getting into the muck of things and breaking down definitions rather than maybe asserting definitions. And, for that reason, it can be a really exciting space, but can also be a really challenging space for people because it asks them to sort of check their presuppositions at the door.

Jenny Champoux: So it sounds like it's meant to be a little bit disruptive.

Chase Westfall: Yeah. Not always and not exclusively, but yeah, that willingness to be disruptive I think sits very much at the heart of a contemporary approach to sort of culture making and especially visual art making.

Jenny Champoux: And do we think about [00:10:00] contemporary art as needing to be relevant to a particular time or place?

Chase Westfall: That's a great point. I think that one of the things that gets sort of slippery with contemporary art is its need appropriate need to always sort of be hunting for what the, what the latest kind of language is. So I guess maybe that might not be an exact answer to your question, but if we think about sort of the temporality of it, it's always about that sort of now, now, now, now, now.

Right? So, whatever it is now, that's the contemporary art movement and that's a real challenge. And, I think where again, we wanna focus on its sort of attitude and its energies and its, you know, demeanor maybe more than we think about the particularities or the sort of formal structures that it presents because what is resonant with and what speaks to, with what you know, what [00:11:00] can speak with urgency to the questions of the day as kind of a constantly shifting target.

Jenny Champoux: Sure. Yeah. Maddie, anything you'd wanna add to that?

Maddie Blonquist: No, I think that's true. I think there's sort of a way of thinking about it where it's like, well, art of the last 10 years, right? Like, because I do think there's maybe a bigger window than just now, but I also think I see a lot of contemporary artists being very referential to other movements in art history and reclaiming those movements and conventions and of traditions in new ways that are relevant now. So, I definitely second everything Chase has said, but I think there's also something about, never completely, it's not always completely original, if that makes sense. There's always a dialogue, it seems to be between the artists that are working today, whether that's through the medium or the process that they're revisiting. Even if you don't see that on [00:12:00] the canvas, there might be a process that they're engaging that is actually, has quite an extensive history, even, you know, hundreds of years sometimes before they are sort of living and working today. I think that referential component is often there, even if what appears to be quite divorced from, uh, an older historic context.

Jenny Champoux: Okay. Thank you. That's helpful.

Chase Westfall: That's totally true. I think that's a great point. It doesn't mean a, now that's severed from, you know, itself. And in fact, I think one of the things that really marks our, our kind of turn in contemporary art is art that's very self-aware about how it situates itself within a continuum.

So, and then there is this other question, you know, thinking about from a practitioner's perspective, how do I make contemporary art now? Which is in some ways a separate question from how does a museum and how does a collection speak to notions of contemporary? Because there, again, you're talking about a [00:13:00] wider sort of maybe set of temporal terms because there is work that was made in some cases a hundred years ago, they can still feel very contemporary in the sensibility that it brings, you know, et cetera.

Jenny Champoux: Well, Maddie, as curator of religious art at BYU, I know you're dealing with pieces that fall into an array of styles, time periods, and even different faith traditions. How do you approach more traditional religious art versus contemporary pieces that maybe challenge expectations? And do you feel like those approaches can ever be in context with each other in productive ways?

Maddie Blonquist: So one thing that my predecessor Ashlee Whitaker did that I always loved about her curatorial approach is she frequently put more traditional or even academic works of art and dialogue with newer pieces. And I think when we talk about [00:14:00] conventional art or traditional art, we're usually thinking of something that's illustrative figurative.

There's a legibility to that, but I think a lot of people find very comforting and familiar and beautiful, and our brains love that because it's easy, right? Like it doesn't take a lot of work on our part to, you know, unpack that. We're like, oh, a tree, a horse, like a man, like, great, you know, and, and I think there's amazing techniques, like the, sort of, the subjects are sometimes a vehicle for an artist to show off their stuff, and we can appreciate that.

And they are sort of making creative choices that I would argue as you get into it, like really are quite cutting edge. But often I think people are intimidated by contemporary art, art that's more abstract in its style that is a little bit less legible in those ways because it asks more of them as a viewer and that can put some people [00:15:00] off.

But what I have found is that it's actually a way of an artist being completely invitational and inviting you to participate in the meaning making of the work. Like I love when artists do not title their pieces. Like I think that's something that people find frustrating when they look at a label and they're like, well, I don't even know what this is called. Like how am I even supposed to find entry into, you know, this work? But it's completely open to you. It just takes sort of maybe a maturity and a willingness on the viewer's part. And I would also say an empowerment to feel like they're allowed, they have permission to engage it and meet it where it's at from their perspective and their experience.

But artists that I've talked to that are living and working today are very, uh, much open. And they know they're gonna, they know you're gonna be there, you're gonna be looking at their work. And that's what they're interested in facilitating, is that dialogue. And for me as a curator, I don't know that everyone really notices this, even though I'm like, what do you think I've been doing upstairs in my office, but I'm [00:16:00] setting up dialogues all the time between artworks.

There are often sort of a title or thematic section in the way that I'm approaching curating exhibitions, and then there's maybe sections the way that, uh, artwork are grouped together, there's sort of a unifying theme or something that I want you to notice or think through. I'm trying to give you tools in your toolbox so that not only can you look at the works in those, uh, sort of that section or that room and find connections yourself, but that you'll leave and come back to other exhibitions or other artworks and be able to kind of do those work in those same modes.

So I find those dialogues, especially between traditional art that's more figurative, that's easier to understand in some ways and next to a contemporary piece of artwork. Fascinating, and I'm doing that constantly. Um, this next religious show I'm working on at BYU will have a lot of that, so I'm just gonna put a little plugin for that.

That show's gonna be up in [00:17:00] the fall and will be up for the next three years. It's called Earthbound and Heavenward: The Sacred Art of Discipleship. And there are lots of pieces that are by artists that are living, artists that are working today and also next to others that have been gone a long time, but there's still a lot of really fruitful connections that they're making even so.

Jenny Champoux: Wow. I'm really excited for that. Thanks for your work putting that together. We'll look forward to seeing that in the fall. And I like the way you talked a little bit about, um, maybe just visual literacy and how you said people are often more comfortable looking at more figurative descriptive of art, more traditional kind of art. But then putting it next to maybe a more abstract or non-representational contemporary piece, helps you find ways to bridge or, or to like carry those skills that you might use to [00:18:00] decipher a traditional piece to a contemporary piece and see that a lot of times the same analysis that you might bring in terms of formal elements or the style help, or even the symbolism, that you can use that same kind of visual literacy in approaching both kinds of art.

I definitely think that's something that from my own experience and having taught art history for years too, uh, it's something that we're lacking in America, that this kind of, there's just a sort of discomfort that I think a lot of people have with looking at art. And I think, like you said, Maddie, really that kind of permission that they feel like they need to their own context or interpretation to a piece.

That at least when I taught, I often would have students feel like there was one right way to approach a piece and they were always looking for like the right answer. But I [00:19:00] like what you said about, having permission to engage with it on your own terms. That's great. Chase, anything you wanna add there?

Chase Westfall: I mean, again, strongly second that I think that there is this really important work to do that good museums do. I think the BYU Museum is a wonderful example of this in helping empower audiences and helping take away some of the anxiety people can feel and encountering new work art has benefited.

I think it's, you know, the role that it has culturally and the way that it's, it's sort of value is taken for granted. Like everybody knows art is important, right? I think one of the ways that it's created that sense of its own sort of value is by, um, perpetuating the story that it's meaning is like intuitive and, and it's welcoming and everybody can sort of get it.

And you can sort of be born an artist and those are really helpful narratives, but they do a disservice to, to people or [00:20:00] they, they, they become a double-edged sword when people have an expectation that they can just walk into a space, encounter a work of art, and get it, and don't understand that what they're seeing is also sometimes an expression of a discipline that is inaction.

That is, that has been pursued for a very long time. And so, you know, I've sometimes said to, to friends of mine who struggle with contemporary art, you know, that you wouldn't, you wouldn't expect to be able to pick up the latest journal of medicine. And be literate in all of the arguments and all the points and all the sort of technical language.

So, you know, don't necessarily expect that you can, by the same token then walk into a space of a different discipline and, and be readily fluent in the very detailed and very kind of particular lexicon, lexicon of that, of that, you know, discipline. So just be willing to put in a little bit of work, be willing to, um, learn the language a little bit, give yourself a little [00:21:00] grace, give the work a little grace and you know, work towards that moment when you'll have a kind of aha with the work.

But anyway.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Yeah. Fantastic. Chase, in your chapter you noted a book published in 2020 by the BYU Art Department. It's called A 15-Year Expanse. And in it, Laura Hurtado chronicled 10 art department alumni and reviewed their contemporary work. What has been the response to this book? Uh, both maybe within Latter-day Saint circles or from the broader arts community.

Chase Westfall: That's a great question. And to be honest, I wish I knew. Um, I don't, I can't say that I have a sense for the broader sort of reception,

Jenny Champoux: Oh,

Chase Westfall: um, and, and shame on me. I, I, it, your question prompts me and, uh, makes me realize that I wanna dig a little deeper and I'd like to talk to some of the folks and, and see [00:22:00] how they felt it was received.

I obviously can sort of speak to my own enthusiasm for the book. Um, I talk a lot about it in the chapter. It was, um, it sort of came to me in a moment when I had a lot of sort of questions about, um, what kind of steps could be made forward in an effective way. And then it sort of exemplified and embodied and modeled a lot of those, uh, for me.

I am hopeful that it's been really well received, that people sort of take it as, as what it is, which is a kind of, um, you know, like a proof, you know what I mean? Like a proof of concept of, uh, a body of people who can be working together in a really thoughtful and faithful way, and also making really compelling art.

Jenny Champoux: Maddie, in your role there at the BYU Museum of Art, do you have any overlap with the BYU Art Department or do you collaborate with them at all?

Maddie Blonquist: I mean, we always want more. [00:23:00] They're currently at a sort of a West campus location. So they're further than they've ever been from us, which I think is a little bit tricky. But the new arts building is scheduled, I think, to be up fall 2026, and they will be right next door. So we're really excited to have that proximity with that department again. I think there's amazing collaboration that happens, especially our educational department reaches out to them. They have open studio nights where they'll invite, uh, professors to come and do a workshop on something like Jen Watson did one on screen printing, I think recently for like the, uh, pop art sort of show with our Andy Warhol that we had up.

So we're always drawing on their expertise and also trying to meet their students' needs as well. So we'll have sketch nights frequently, or you can apply for a sketch pass at the museum to just come and, and draw and sketch and kind of, you know, learn from the masters, uh, that way. And, um, so there's all [00:24:00] kinds of program that we gear towards art practitioners. Both in our community but also on campus. I had a really great experience collaborating with Madeline Rupard recently, who you feature one of her works in this show. She's also, uh, newly appointed faculty in the BYU Art Department, doing an amazing job. And we, um, the museum had an opportunity to display Eight Approaches, which is a work, an eight panel, uh, triptych, octtych, I guess you you might call, um, by Joshua Meyer, who's a Boston-based Jewish artist.

And this work was all about sort of Hanukkah and commemorating that religious tradition in the way that he remembered it and memory and it really beautiful work that we had up for a very short period of time. And, Madeline and I worked together to bring him for an artist talk, so a Q&A that we hosted at the museum and many of her students attended, but we also set it up so that Joshua could work with the students before he [00:25:00] arrived on campus. Sort of a one part, two part, situation where he gave them a lecture over Zoom and then the students created work inspired by him and his art style. He's this sort of a distinctive palette knife approach to his panels. Um, and then that same day we had the artist talk, we ran over to that class with Madeline and he critiqued like, and reviewed and workshops all their work with the students.

So I think at like peak, that is like what we would wanna be doing every day with the art department. Um, but we, we certainly would love to do, you know, even more things like that in the future I think.

Jenny Champoux: That sounds like a really exciting collaboration and good things happening there. Yeah. Chase, as I was reading your chapter, I was reminded of Art and Belief movement, which was covered in one of the other chapters. We talked about this in episode five of this podcast, and it seemed like these Art and Belief movement artists who [00:26:00] came out of BYU mostly, um, never really found an audience because they were too religious for the broader art world, but then they were too weird for a Latter-day saint audience. Is that still the case today with contemporary LDS artists? Do, do they feel like they have to choose one audience over another, or can they ever kind of find a happy middle ground there?

Chase Westfall: That's a great question. I'm gonna sort of, I'm gonna start by not speaking to the question directly, but acknowledging something that your question helped me realize when it comes to sort of art and belief I've had. On the one hand over, over the years as again as an LDS artist, been really drawn to some of the work that, that came out of that moment outta that movement, as coming from the perspective of like a painter, which is where I sort of started my kind of artist journey.

Those were some of the kind of most exciting LDS paintings. Things that, um, [00:27:00] helped encourage, inspire me to feel like this was a, you know, that, that art was a place where I could express my sort of spiritual self. Um, but I think there is a sort of, there's a consensus that, that their vision wasn't ever quite achieved or wasn't quite realized in the way that they would've hoped.

So there are these, there, there are all these little lingering questions around them, and one of the things that I realize is that, that they, I think give, they deserve more credit than I've given them in the sense that I've always seen them as this kind of, kind of, um, again, like, like they couldn't ever quite make a breakthrough into the cultural space within the Church that they had hoped or into the broader cultural space within, in the way they might have hoped.

But they did do something which no one else has sort of done, which is to sort of be a moment, be a movement. We're talking about it now. There's a chapter dedicated to them in the book. So, I'm taking an opportunity to sort of like, maybe just admit that I haven't [00:28:00] probably given them the sort of credit they deserve, and maybe even culturally we can, we can do more to think about the success that they had because, you know, for better or worse, they are an established thing.

They are a really crucial cultural touchstone for us, um, in ways that I think other groups that have given up that fight and decided, well, I'm just gonna lean church, or I'm just gonna lean, um, you know, secular, um, you know, haven't been able to, haven't been able to achieve that. So, I don't know. I, but I do think to your question, that artists still do sort of struggle with this feeling.

I think that feeling is going away, but it is still there that I have to sort of choose between kind of a faithful approach, a really sort of neatly, culturally aligned approach, an approach that's sort of palatable to an LDS audience. Um, and or an approach that sort of caters more to my wild side maybe, or, you know, to the, um, the sort of [00:29:00] the more, um, permissive sensibilities of contemporary art.

I think people often feel that they come to a why and they have to sort of go left or right. Um, I think that that feeling is something that can be sort of challenged and worked through and sort of debunked. That's one of the things that I try to talk about in the chapter is that, you know, in my experience, when you actually look at what is working in contemporary art, people are very open about all kinds of very, sort of powerful faith experiences.

I think where it gets sticky is when people want to use contemporary art as a space for, um, religious exploration. Uh, or maybe to put it another way, if they think that they can sort of roll their comfortable experience and expression of their, of their own religion into a contemporary art space, they're gonna be in for a little bit of a, of a, of an unpleasant surprise when that religious sort of [00:30:00] sensibility is sort of challenged and broken down and brought into question, and kind of brought into the muck, as I said, as as contemporary does in many things.

Whereas on the other hand, people who bring what we might call less, you know, an exploration of religious sensibilities and whether we might come more like an, an, an, an exploration of their kind of faith journey, we'll find that that faith journey, um, expressions of which are really welcomed within contemporary art, right?

So, um, to the extent that they can maybe reframe their practice and think about it less as exploring their sort of. Again, like their religious sense of self and more of their kind of like faith journey. They can, they can find a good audience there anyway.

Jenny Champoux: Okay, so maybe they feel like they have to be a little less overtly religious or about a particular religion and more just kind of a spirituality

Chase Westfall: You know, there is room to sort of see Art and Belief [00:31:00] more from the lens of sort of being a success, right? That they, that they did something important in that they modeled the tension, um, of trying to be their authentic selves in, in a space where, or in answer to two cultural spaces, neither of which was completely comfortable with them exploring that full, authentic range of self.

Right? To your point earlier, I think the sort of secular audiences weren't quite ready for, or weren't quite attuned to the spiritual, um, kind of rawness that they were bringing or, or, um, the particular spiritual perspectives they were bringing. And an LDS audience wasn't comfortable with explanations of faith that were as kind of vulnerable as the ones that they were putting on the table.

Um, and so that vulnerability maybe is where the key factor lies, that if people want to make contemporary art a space for [00:32:00] you know, uh, evangelizing or simply kind of perpetuating, uh, conventional lines of religious thought. they're gonna find that being challenged consistently. But if they can bring their, again, authentic spiritual journey, uh, which could even be an explicitly LDS spiritual journey, there's nothing that, that demarcates that, that says that that's out of bounds.

Uh, whatever your kind of spiritual path is, LDS or otherwise, I think as long as it's worked through in a really raw and honest, and vulnerable and open way, contemporary art will embrace that. That's been my experience. Um, and maybe not contemporary art. I won't necessarily speak for the market, but I'll speak for sort of the peer group and the community and the artists themselves.

There's a lot of openness to sort of faith expressions of every kind. As long as they, as long as they're, you know, like honest.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I think that's a great way to put it, that emphasis on the vulnerability and honesty. Maddie, what about you? Do you [00:33:00] see Latter-day Saint artists feeling like they have to tone down the religious elements of their art to be taken seriously in the art world outside of Utah?

Maddie Blonquist: I mean, I think I agree with Chase in that I, it's maybe less so than it ever has been, although, I do know that one of the questions that came up actually when we were doing that Q&A with Joshua Meyer was, How do I as a student, like incorporate faith into my art practice? So this is, you know, this is as recent as, you know, a few months ago.

So clearly students at BYU, at least are thinking about this question, and that makes sense to us, right? Like we, we know that it would, because there's this dual heritage there, this mission to produce disciple scholars that whatever major you declare, you are doing it sort of in a spirit of consecration. And I think that's wonderful if, if people want to do that. My, I have a couple thoughts about this. [00:34:00] One is that I think we can't dismiss the importance of venue. I think there are certain, there's a lot of different kinds of contemporary art. There's a lot of different sort of registers and tones that, that it hits. And I think that. There's a landscape, particularly in Utah where I am based, um, of amazing venues that will allow certain contemporary art to be shown, maybe to better reception than others. And so, BYU Museum of Art, for example, like we will be having a Trevor Southey in the next show. And we've had, we've showed Trevor Southey in the past and we've showed Gary Ernest Smith and we've shown, you know, Bruce Hixon Smith.

You know, like there's, there's members of that kind of Art and Belief movement or that sort of time period that have established themselves as artists working within the Latter-day Saint tradition and with Latter-day Saint or, uh, religious subject matter. And they've done that successfully and it's sort of demonstrated that [00:35:00] it's, uh, it's held up over time. But I also think there are, you know, the closer you sort of move to like the nucleus of the Church as an institution, that sort of flexibility might change. So what is accepted in the International Art show, um, at the Church Museum, that is gonna be different than what can come in the Spiritual and Religious that Springville does.

So I actually love that there's this network. Um, I feel it's very expansive and abundant in the way because know that if there's something that doesn't feel like it's as good of a fit for BYU, there's probably another institution even within an hour drive somewhere that is gonna be a great place for that to be.

And so I think that would be my sort of for artists is to think carefully about, you know, do the art that you feel is, um, is important for you to be making. And [00:36:00] that if your Latter-day Saint identity, um, is an important part of your process or of the subject matter you're dealing with, um, like, don't take that.

Don't, don't take that out. If that feels authentic or important, like lean into that because there's a lot of other identity markers in the art world that are being given, given a lot of space right now. I mean, and some of those are, you know, racial or geographical or, you know, there's lots of different ways that identity is being explored in contemporary art that is acceptable.

I think religion and religious identity is one that we are becoming more. Comfortable with. It's sort of, it hasn't been as sexy to talk about, but I think now there's a lot more discussion and exhibition sort of dealing with this in secular spaces. And maybe the treatment of those curatorially or academically is a little bit more but it doesn't mean that it doesn't exist.

So it's about venue for me. Um, the other thing that I, I [00:37:00] would say, and, and this is a quote that you have in your chapter, Chase, you say, “In my personal practice, I had spent enumerable hours hashing and rehashing the question of what it meant to be an LDS person making contemporary art.” And I first love that you sort of distinguish like you're an artist who happens to be LDS.

Like I feel like that's an important kind of way that we can talk about it and the, the book necessary, like necessarily, excuse me, necessitates the use of that of right Latter-day Saint art, Latter-day Saint artists. We can't really escape that in this book, but I just wonder if this is something that we would find an easier time navigating if we look to other examples of artists that are working within a faith tradition that are also having to think this through.

We have some unique pressures that I, I think the book lays out pretty But, um, is this something that like a Catholic artist or Jewish artist or a Muslim [00:38:00] artist, like, are we even talking about this in those ways outside of our tradition? And if we aren't, can we move into that modality as well and find that helpful in resolving some of these things internally for ourselves as creatives?

Jenny Champoux: Hmm. That's a great point, Maddie. I like the way you're thinking about that. And I like the way you talked about thinking about venue too, as you know, that artists maybe need to think about the right space for the art that they're making. Just kind of a follow up question for both of you. Are there other steps that can be taken to try to position Latter-day saint artists more meaningfully in the contemporary art world? Chase, do you have any thoughts on that?

Chase Westfall: Um, I think again, sort of building a, uh, kind of credible and exciting kind of critical mass of conversation around some of the strong examples of work that we have would be really [00:39:00] helpful. I think that there's a, um, because of the kind of precarious relationship that, um, contemporary art has to, again, mainstream LDS culture and even to a certain extent like, you know, like the Church as a kind of organization, there, there, there's a feeling that our best products, best cultural products as people are somewhat sort of adrift, right? And so if there was I think a sense of more buy-in and momentum from our audiences, uh, from our academics, from our institutions, uh, if external audiences felt that we were more kind of rallied around our artists, I think they would, um, um, be sensitive to, susceptible to the feeling of enthusiasm that we could bring to arts.

So sometimes I think it's maybe just organizing ourselves a little more as a people so that when someone from the outside comes in and, and encounters an example of LDS work, they can feel that there is some weight behind it, that it isn't [00:40:00] just a kind of a little island that's adrift out there. That's one thing that sort of comes to mind and that sort of tails into thinking about systems of patronage.

Um, you know, one of the sort of shame on me, I had this epiphany in my thirties when it probably should have been self-evident when I was in art school, you know, like in my twenties. But like, um, it, it, it, I realized that all of the sort of canonical works I was familiar with, um, that were in the National Gallery of Art in DC were canonical because they were there. They weren't there because they were canonical. Do you know what I mean?

And so if we can be more thoughtful again about, um, creating systems that position our best works in a place that they can then be absorbed into the canon, that will be a really thing. And that has to do, as I mentioned a moment ago with just maybe organizing ourselves a little better.

So [00:41:00] that, um, we can create some of those, um, uh, conspicuous places for some of our best stuff. And that would also include maybe somewhat crassly, just better systems of like patronage. I think outside of the Church, can we tap into some of the Silicon slopes energy and in the way that young, you know, like young, wealthy, you know, upwardly mobile, people are supporting, uh, contemporary art in other spaces around the globe.

If we could get them to do so there in Utah, for example, um, then, you know, those, those, those collections mature and they go into museums and then they become part of the discourse and then that is a way of building momentum.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Chase, I'm thinking also of the Great Awakening show that you curated for the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts and, and because I think that was largely contemporary,

Chase Westfall: Yeah, I would say, I would say exclusively contemporary and.

Jenny Champoux: Exclusively. Yeah. So that, I

Chase Westfall: Yeah,

Jenny Champoux: [00:42:00] I think that's a great example of an organization and, and people that are giving a, a platform and a, like a showcase to this kind of Latter-day Saint contemporary art, bringing it to the attention of a larger audience.

Chase Westfall: absolutely. I think, you know, I think the center is doing a lot of amazing work. I think Wayfare is doing a lot of amazing work, and I say that speaking a little bit outta turn because to my, to my shame, I haven't invested in that space as much as I ought to have. I, I, I am actually, I have a, a to-do list item. It's, you know, convenient because we're doing this conversation, but I swear I have a to-do list item this week. I'm gonna finally get my subscription to Wayfare, right? Because like, I, I know that I have to sort of walk that walk also and be more invested in, um, bringing whatever I can, um, in terms of consecrating the best of my abilities to helping, uh, you know, sort of gather the storm and, and make sure that some exciting things can happen, that we have that critical mass within our own kind of.

Within our own cultural space. Um, but yeah, so there, there's, there [00:43:00] are, there are the beginnings of, and I say this even in my chapter, but I think, you know, I think this book, um, uh, whether my chapter helps this or doesn't help us, I don't know. So I, again, in a disinterested way, I would say that this book and the fact that it exists, um, these are the kinds of things that will hopefully help us get the momentum that we need and, and start to break through into some of these other spaces.

Jenny Champoux: Mm-hmm. Yeah, I think you're right that these are all good things and, and Wayfare certainly is doing a good job of bringing lesser-known artists, um, to the attention of a broader audience. And they, they do a really nice job of incorporating visual art into all their publications. I'll say just personally a personal plug here for my Book of Mormon Art Catalog, that's a, you know, a website I've built to try to gather Latter-day Saint artists from all around the world who [00:44:00] are engaging with the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants and Church history.

And, I hope gives them a platform to also reach a broader audience that people can more easily find a variety of art, um, or international artists, um, or different styles. We definitely have some abstract, uh, pieces in there that people may not be as familiar with. And, um, I just think that having that variety is really important to, um, about how art can inform our reading of scripture, um, and, and, uh, and having a greater variety, I think is important there. Maddie, anything you see that could be useful to help Latter-day Saint artists be taken more seriously if they're working on religious subjects?

Maddie Blonquist: I mean, I think my, I'm well positioned to participate in that. I [00:45:00] think other curators have demonstrated that this is, curator, like that the institutional liaison plays a huge role in introducing new artists and giving them validity. Um, at, I think there's, I mean, there is institutional trust, right?

If someone comes into a museum and something's on a wall, the assumption is this is good art. Like this is, this is important. There's something noteworthy about this. We should be looking at it. Um, there's a, there's a cultural value that is ascribed to that, that already, and actually monetarily as well, because as works of artists enter collections, the value of any other works, other people own and private collections increases.

And so there's a real, um, currency to that, that I take very seriously. But I think in the one thing I love about this book this reader is that, and I think it's very clear about its objectives to do this, but I mean, it's published by Oxford University Press. Like this is not something that is, [00:46:00] um, sort of, uh, self-produced. It is going through a rigorous peer review process. Um, it's done by academic scholars, curators, people who have been doing this for a while. Um, it's thorough and everything that I think the editors and project managers hoped that it would be.

When I'm writing text, especially for that I'm sort of lifting up, we've got a few works in this next show. One is by Amelia Wing, the other is by Elise Wehle. These are women artists that are working in Latter-day Saint spaces that to my knowledge, we have never shown before in our venue, but have sort of made their way actually in, in Wayfare, both of them and, um, other spaces. And I'm really pleased to be in a position to sort of help take their careers to maybe the next level by acquiring their works into our collection or, um, showing them on display for a longer period of time.

[00:47:00] And writing text in a thoughtful, thorough a way that demonstrates the value of what they're doing aesthetically, even if sort of there is an inherent accessibility to those works because they are beautiful and interesting to look at. But I think they're doing something too that's worthy of intellectual engagement. And as a curator, you know, selecting the works and then contextualizing them in a way that does them justice. Like I feel like that is the work I'm trying to do every day. And I mean, there is, there is impact there. I mean, Jorge Cocco Santangelo, who is, is very saturated now. Like we, he is super recognizable and that sort of sacrocubist style that he does and people love him, but he didn't, you know, this was sort of a discovery that was made not that long ago and it was because a curator thought there was something interesting there and put it up.

So there is, [00:48:00] you know, impact on the market. Um, and in the visual material culture on the ground of members, you know, these prints end up in people's homes.

I think that that, uh, sort of or trickle down process that I'm engaged in, um, I'm very aware of my position that's in that um, again, wanna do right by everybody, the artists and the community that we, that we serve.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Fantastic. That's really good insight. Thank you, Maddie. Okay, we've gotta get into some of the artworks here. Chase, in your chapter, I loved the piece by, is it Jason Metcalf?

Chase Westfall: yeah. Hie to Kolob is the name of the exhibition and in and in fairness, I do it a little bit of a disservice because I refer to it by the, the title of the exhibition when, you know, all of the, all of the independent works also have titles and, and ought to be extended. The, you know, the, the right that they have of having a life of their own.

But I just lump 'em all [00:49:00] together, so shame on me.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Okay. So it's several different pieces, but organized into one sort of group show. And I just felt like this piece really encapsulated the point you were trying to make in your chapter about how contemporary art shifts from the depictive to the sort of questioning or interrogating mode, and less represented, like less figurative or representative too.

So walk us through this piece. Tell us about the different pieces and, and how it all comes together.

Chase Westfall: Yeah. In fairness, I think it should be admitted, I did not ever, I didn't see the exhibition in person. Right? So my understanding of the exhibition comes from documentation and from conversations that I've had with Jason and with others who did experience the, the installation firsthand.

So, as I sort of talk about in the chapter, it's almost kind of like a diorama, and that immersive quality that it has is, is I think one of the things that, um, is sort of [00:50:00] an ear marker of what we would call sort of contemporary art, right? Um, it's willingness to embrace different modes of, of, um, making within a kind of comprehensive, kind of unified gesture.

Um, the fact that it, um, uh, you know, embraces its own kind of like theatricality. Um, that it's sort of self-aware in that way and that it's willing to, um, think more about, maybe, sort of more holistically about an, an instance of encounter, right? And the affect and sort of the feeling and the mystery that all of that might carry with it, rather than just trying to communicate a specific message or a specific, uh, narrative or et cetera.

Right? So, um, the viewer comes in and steps into a space, and within that space there are a series of paintings hung along the wall. And the space itself goes from being dark at one end to sort of being brightly lit at the other end. And the, the paintings that are there hanging on the wall are kind of [00:51:00] matched to the gradation.

They don't, um, they don't obviously touch on every single sort of. Moment within that transition, but they sort of step out for the key moments from, from almost sort of pitch black on the one end to basically like a fully brightly lit kind of like white painting on the other end. And, um, what, you know, there are many ways in which you could interpret it, but, but the, the sort of title tees it up for one kind of interpretation, which is a visual and experiential standing for the sort of spatial journey that is referenced in Hie to Kolob.

Right? Like, one of the very unique things about LDS doctrine and cosmology is this belief that, you know, God is an embodied being who lives on a planet, right? And there's a sort of, there's a, there's a physical concreteness to his existence. Um. And so Hie to Kolob puts this kind of really radical, kind of doctrinal belief sort of front and [00:52:00] center by sort of spatializing this journey.

And then also at its conclusion, um, once you've moved from the darkest part of the gallery to the brightest part of the gallery where you encounter the bright white painting, which in many ways is again, kind of like a symbolic of maybe being in the, the celestial space or celestial presence. There is also, um, a plated, a sort of a, what it's called, a paved work of pure gold is the name of the individual gesture.

So it's a sort of 12 inch by 12 inch square, um, gold plated piece of aluminum that sits on the floor that's sort of spot, and there's this incredible kind of plume of golden light that sort of bounces off it. And then, you know, uh. So by virtue of that sort of golden square, we sort of symbolize either God's direct presence or a place where God could come and sort of stand and be present.

Um, so I mean that's sort of the, the, the setup to help [00:53:00] viewers kind of maybe understand what, what that encounter is like. Um, and it, it doesn't sort of shy away from I think the kind of radicality of some of our more heterodox, more sort of hetero if you think about sort of within the mainstream Christianity, right?

Some of our sort of more strange, um, um, beliefs and, um, because it sort of situates them there directly and states them directly and doesn't kind of mince words in that regard. It, it does sort of feel very kind of like revelatory, right? You have, um, a kind of collision with this kind of bold, new concept of the universe that is part of the understanding that comes out of the restoration.

Um, and so as I, as I try to talk about in the chapter, I think for people who are not LDS, this is a kind of really radical concept. Um, or, you know, the different concepts that the, that the, um, installation is built from are all very kind of strange and radical and new. And [00:54:00] even for persons coming from an LDS perspective, it asks us to kind of put our money where our mouth is and take, take literally and take seriously some of the things that we, um, might compartmentalize and not be actively considering as part of our kind of daily experience of faith.

Right. Um, so, you know, all that said, you know, there's, there's again, paintings, sculpture, there's this sort of theatrical lighting set up. So, um, Jason sort of does all the things to put you in this place where you feel, um, um, exposed to a whole new kind of other reality, and you have to kind of sit with it and be in it and deal with it.

Jenny Champoux: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Great, great discussion of that. I, I think this is such a great example of, um, maybe what we mean when we're talking about contemporary Latter-day Saint art. That compared with of the art we see as Church members, [00:55:00] so, you know, the sort of illustrations of scripture stories like, um, Arnold Friberg or Simon Dewey, and which is wonderful and certainly has its uses, right, and is, and is useful and, and important. Um, but this is such a different approach, right? That it's not trying to be didactic, it's not trying to teach you a particular story or a particular message, but it's just opening space for you to think differently and to think theologically, I think. Right? To encourage you to really, um, engage with doctrine and the scripture, um, but in a very embodied way. I like the way you talked about how you actually move through this space and the light changes and it's theatrical and it's almost like you as a viewer are part of this performance of the piece as you move through it. And, um, and I think lends to that materiality that you talked about. [00:56:00] Um, I, I just think this is an incredible piece and, and your analysis of it in the book was fantastic. And, um, and I thought showed your analysis, showed some of the, just new ways of thinking that this piece opened up for you and for me, reading your, your analysis of it. So yeah. Thank you.

Chase Westfall: Well, I appreciate that very much. Yeah.

It confronts us with some of the things that really test what we might think of as our, um, understanding of ourselves. As sort of spiritual beings and as Christians. So, um, that's heavy lifting, right? And an artwork that can put in that place is doing meaningful work.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Maddie, is there a Latter-day Saint artist that you see that is doing successful contemporary art that you wanna mention for us?

Maddie Blonquist: I mean, there's so many. I, I think there's a few that are gonna be well known and established at this point. Um, [00:57:00] I think. I, I'll say Bruce Smith again, just because he also taught a next generation of artists as well, like J. Kirk Richards, um, I, I see artists I think, that are the most successful in navigating all of these different venues, um, that have appeared in multiple places.

Like, I think that's what I'm looking at again, just thinking about like who is able to, um, sort of pivot and, and make sense to a variety of members in the community. And I think both of them have, I think it's because are meeting people where they're at in terms of like, here's something you can recognize. Here's a human form. Um, but here's my way of stylistically interpreting it that's doing something different. And of course it's still beautiful. I mean, that's [00:58:00] not a word that I think a lot of, uh, of cutting edge contemporary venues are looking for in their art is they're not saying, well, give us the pretty stuff, you know, and that's fine.

I don't, I think there's an incredible value to looking at things that you don't like. Actually, those are the experiences with art that are the most meaningful to me. and that push me and I think in, in growth for me as a person. But I would say those that have sort of proven their success, um, that would be good for artists working now as they're sort of starting out to maybe look at are those like Bruce Smith and J. Kirk Richards, who have found a way to appeal to a diverse number of audience audiences, but also maintained integrity in their own style and approach. So I don't know those are who I would mention. There's amazing people doing incredible things. [00:59:00] Like I think Jason Metcalf is an incredible artist. I, I love the examples that you picked Chase, because that to me is like art.

Even the ones that you mentioned, um, that are not necessarily Latter-day Saints, but they're engaging ideas that would resonate with members, like prophecy and, and those other things. I think those are hallmark examples of exactly what you're talking about. But for me, in terms of who sort of the test of time and demonstrated success over a long period that we can recognize and maybe learn from for the next generation, those are the two that I think of.

Jenny Champoux: Mm-hmm. Maddie, you mentioned earlier you maybe think of contemporary art as art from the past 10 years, so let me ask you, where do you see Latter-day Saint art headed in the next 10 years? Or where would you like it to be headed?

Maddie Blonquist: Well, I mean, maybe I can revise even my previous, one thing I didn't say, but I do think is important is to, to note that all art is contemporary [01:00:00] art. Because at some point it was new. So that's sort of the first, the first thing. But then also there are contemporary modern viewers that look at it now with their own context and make it new again.

So, um, I think, I think that's important to note. In terms of the next 10 years, I am hoping Uh, again, I mentioned I feel strongly about giving people tools and empowering viewers. Hoping that we'll see maybe not on the artist's end because I think they're doing amazing things. I'm not worried about them, um, on the audience and reception end. People that are more open to looking at whatever the artists are making. So that is maybe not the answer you would expect, but, but on my end, I'm, I'm really thinking about our audience and how can we equip them receive the amazing things that artists have been doing and will continue to do, um, so that [01:01:00] we. We can basically try, you know, Art and Belief over again, but we'll be ready for them this time. So my hope to see is I hope to see more, um, audience engagement. I, I wanna see and support, um, spaces like Wayfare and, uh, compass Gallery. I mean, Faith Matters, they're all sort of a, a unit. But, um, you know, all of those spaces that I think are are doing that legwork of, representing new artists well, but also institutions that are participating in educating viewers and collectors. There's a really rich, um, of people dedicated to the arts and their respective spheres.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Chase, in your chapter one part that stood out to me was you said a revolutionary theology calls for a revolutionary art. Talk to us about what you mean by that and, and where do you see the art headed in the next 10 years?

Chase Westfall: Um, [01:02:00] well, what do I mean by that? Um, I think there is a hope, and maybe it's a sort of a romantic and idealistic hope, but you know, we can have a cultural impact that's as radical as the theological impact that we've had. I mean, the Restoration transforms the world and, uh, can we have, um, a similar world transforming impact through the, the, the other kinds of cultural products that are attendant to the restoration.

Um, but you know, that's also, it is also that kind of thinking that, um, creates the, some of the challenges that we face. So, admittedly, I'm sort of even as I'm trying to maybe be part of the, or or provide pathways for, for a solution. I'm also, in some sense, part of the problem because, um, uh, statements like that, you know, put pressure on us to do something that's really exceptional.

You know what I mean? I sort of, I sort of feel that [01:03:00] pressure. I think other artists feel that pressure and that pressure isn't always healthy, but, but I do hope I hold onto the hope that we can. Um, we, you know, as a people can, can put some things out there, um, that will astound ourselves and astound, you know, our kind of audiences.

I think high to call is an example of that, and that's one of the reasons that I think I've given as much attention as I have.

Jenny Champoux: Where do you think we're headed with Latter-day Saint art? What do you see as being the trends coming up in the next 10 years?

Chase Westfall: I, I honestly don't know. I think one of the things that, um, you know, I, I sort of outlined some hopes in my chapter, um, but they are, um, you know, contingent upon certain trends that are, that are happening contemporary art now. And if those trends shift, I should say maybe when they shift, um, then the goals might shift accordingly.

But, um, we are in a moment where there is a lot of openness to different [01:04:00] kinds of, um, earnest explorations of faith. And so if we can spend the next couple years and move quickly to kind of break down the residual kind of mistrust that we have of, uh, you know, collectively as a culture of, of contemporary art.

Then we might be able to sort of make some hay while that sun shines and get a version of the authentic faith journey, um, enmeshed in there alongside all the other beautiful expressions of the authentic faith journey that, that are part of contemporary art. Um, I'm really looking forward to, you know, A 10-Year Expanse: Volume Two.

Uh, I don't know if BYU is gonna come through with that sort of intimated promise, but I'll be looking to take a lot of my cues from that. I, you know, I have kind of an implicit trust in BYU and their art department there. They've, they've shown over the years that they're worthy of that trust. They continue to do exciting things.

And when I get a little, um, curmudgeony [01:05:00] about the state of LDS culture, um, they will always produce something that helps, helps me get past my cynicism again. The first version, volume one, was a great example of that. And, you know, we mentioned Madeline Rupard earlier, that Madeline's, you know, joining the, the faculty there alongside some of the, you know, all the incredible folks already there is, is cause for optimism on my part.

So, um, I don't know. I think if we sort of move fast, um, and if we can continue to build from the, um, the sort of systemic support that some of these organizations that we've already talked about, providing that within a few years, I, I really think we could see one of our folks break through into, you know, like the Whitney Biennial, kind of like one of the moments in a meaningful way.

Um, and that would have a lot of cascading and sort of trickle down, uh, door opening effect.

Jenny Champoux: Mm-hmm. Yeah. You know, I was really inspired in your chapter, your kind [01:06:00] of call for Latter-day Saint art that looks, as you said, authentically and honestly at the doctrine and the culture and the history, but in a way that is not apologetics, that's not trying to tone it down or sugarcoat it or idealize it. But is also not looking at it as something that's like spectacle or comedy as is often done. Right? But that there's some, there's a third way where it's just an honest engagement. And I think as you said, let the doctrine speak for itself through the art.

Chase Westfall: Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: I think that's a really great, uh, a great way to think about, um, an exciting way to move forward with Latter-day Saint religious art.

Chase Westfall: Thanks. I appreciate that. I think it's, yeah, the, the doctrine is, is radical. Let it, let it do its radical work. Like unleash it, you know? [01:07:00] Um, and, and not just the doctrine, but also our values, you know? Uh. The, I mean, I am, I am totally converted to, you know, the values of Christian discipleship and in my life experience anywhere that those are applied unapologetically in a spirit of love and the spirit of sort of truth, amazing things happen.

You know, and if we can sort of get out of our own way and apply our discipleship with that kind of earnestness in the sort of the cultural sector, I think incredible things can happen.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Okay. I am ending every episode by asking our guests to share, um, an artwork that is meaningful to them. And it could be contemporary art here. It doesn't have to be, um, just Latter-day Saint artwork that you feel like you'd like to tell us about. Chase, why don't we go to you first?

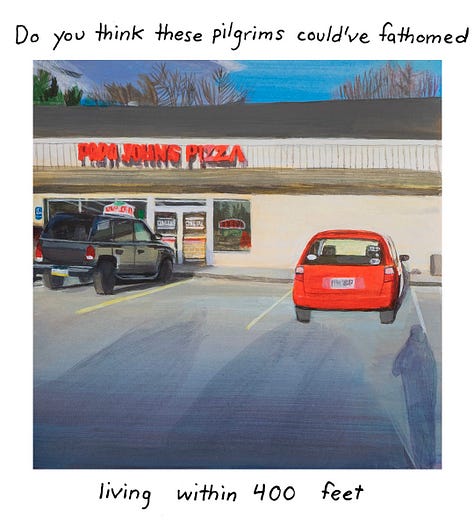

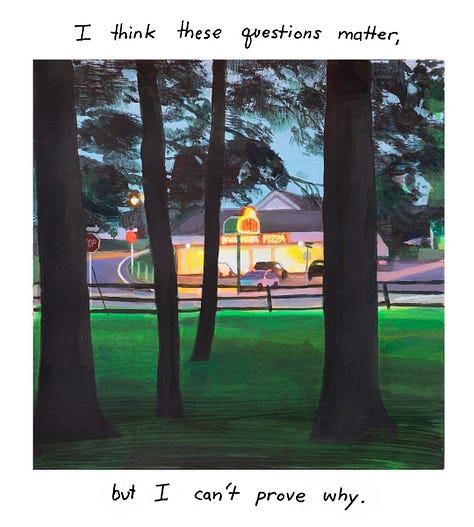

Chase Westfall: You know, I, I actually, I mentioned Madeline came up, Madeline Rupard came up earlier in the, in the wonderful sounding [01:08:00] collaboration that you all did. And I mentioned her just a moment, her recent, uh, um, recently joining the faculty. And so, uh, the piece that comes to mind for me is a piece she did recently called Father Johns, and you can find it on her Instagram account.

Um, I, I love Madeline's work for a lot of reasons. Um, it is a really beautiful embodiment of some of the things that I have kind of clumsily hinted at today, right? Like a person who is just working through their faith via the tools of, um, creative expression. Um, taking, taking the skillset that she has as an artist and applying it, um, in an earnest way to the, the big philosophical and metaphysical questions of her life.

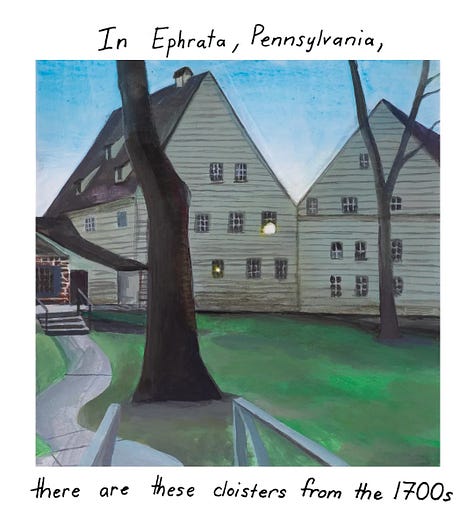

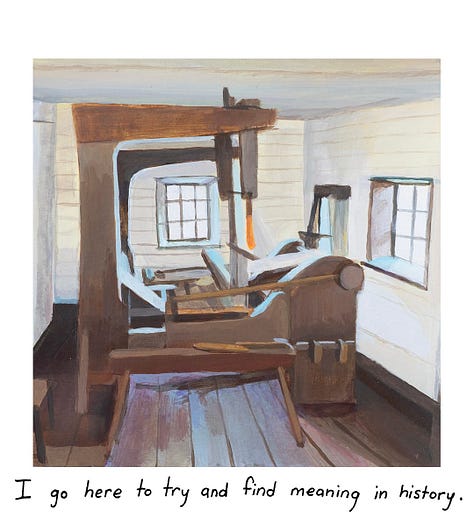

Um, and doing it in a way that reflects the, the, you know, the absurdity of, of, of daily life and the sort of strangeness and alienation and the, again, the even sometimes the indecency [01:09:00] of a daily life, right. So, but this one piece, Papa John or Father John, um, is a quick series of images with accompanying text where she's sort of narrating her thoughts about the perverseness of a Papa John's pizza being next to this, um, old cloisters.

Um, that was a, a monastic cloisters that was built. And let me, I'm looking at my notes to make sure I get the town right. Ephrata, it's called the Ephrata Cloisters. It's at Ephrata, Pennsylvania. I've never been there, but I think it's something like a, kind of like Shaker village, right? There was a, a religious community, a, a community of monks that live there.

And so she's navigating the grounds and kind of reflecting on the legacies that they speak to of faith and scholarship and all that, you know, monasticism stands in for. And that now in the contemporary mode across the street, there's this Papa John's pizza and she, you know. Among the many sort of beautiful and wonderful observations that she makes, it ends in the last frame with [01:10:00] this text, which for me is just, I don't know, it feels like it sort of hits the nail on the head of, of where art does its beautiful work. And so it says, after asking these questions of herself, right, she says, “I think these questions matter, but I can't prove why.” Um, willingness to acknowledge, um, that I think these things matter.

I think art making matters. I think making a painting can have value for someone in some way, even though I can't prove why. You know? Um, and I think if, you know, I won't say if we are honest with ourselves. I'll say if I am honest, the same kind of thing can be said about my discipleship journey. Like there are times when I have big questions and there are times when things get cloudy and you don't know what's going on, and you have hopes and you have fears, and you have all these things.

Um, um, but in the end, what holds you there is that thinking that these things matter, even if you can't always prove why. Um, so I, I [01:11:00] just, that resonated with me in a really profound way. So I offer it, uh, a, a, an answer to your answer to your question. I encourage anybody to go check out Madeline's Instagram and look for that piece in particular.

It's really, it's really beautiful.

Jenny Champoux: Thank you. Yeah, and we'll try to put it in our show notes.

Chase Westfall: Yeah. Thank you. Because I did not give it a description convoluted. So.

Jenny Champoux: Okay, Maddie, let's go to you.

Maddie Blonquist: Yeah, so I mean, so many, right? Like, this is such a hard question,

Jenny Champoux: I know.

Maddie Blonquist: um, it related to sort of what direction do we see it going? I, I do think the works that we've recently acquired can kind of speak to like that trajectory and like what are we acquiring now? What will be up, sort of what's been up for three years, what's gonna be up for the next three years?

So one work that um, we recently acquired that was in the last show and will be in this show, is a work by Paige Crosland Anderson.

I think her name will be familiar to many, if they don't know [01:12:00] her name, they will recognize her work. It's very distinctive. Um, and we have her, um, Atonement triptych, which is the three-panel work that shows each, uh, phase of Christ's atonement.

So there's Gethsemane on the left-hand side and on the right-hand side there's sort of a crucifixion type. And then there's in the center panel a resurrection type of page. If you've seen her work before, you'll know she is an abstract artist. She doesn't deal with, uh, human forms very often, at least not in the, in a strict, readily um, legible way. And she instead is inspired by, um, quilt work and quilting and sort of the history of women's work and domestic art forms. Um, and also, you know, other, other sort of patterning [01:13:00] that we see in nature and sort of these other everyday, um, ways that pattern crops up. She's very fascinated by that and so I love that she's taken in her painting, which is sort of on the hierarchy of art historically at the top, you know, sort of, it's like painting and sculpture sort of like at the top. And then you have something like quilting, which is a craft or a fiber art form that is done mostly by women in the home, rarely on display. And so has again, that sort of referential dialogue that I think artists even now engage in still.

She has created a painting in the form of sort of a patchwork quilt that is about the savior sacrifice. And she will sand things and she will repaint layers there. She doesn't, um, I don't believe she uses anything. Like a straight edge or anything. So she's doing these all meticulously by hand. So there's an incredible amount of time and effort that you can see just on the canvas.

Like this must have taken hours. So the [01:14:00] labor is very apparent. Um, and yet she's touching on these really universal Christian themes and theologizing, um, in this work that is sort of pointless or um, you know, abstract. And so I love that. She, again, I think is, I've mentioned kind of Bruce Hixon Smith and J. Kirk Richards who maybe have done and contemporary work that has worked.

I feel like I see Paige sort of that next push in that direction to get people feeling that much more comfortable with abstraction. I find it incredibly meaningful and, uh, devotional. That's one of my favorites that I think we have. And she's got many others. Um, Wayfare I think, has featured her in several of their issues.

The last issue, I think she was a main essay and a new work she created just for that. So she's a great one and [01:15:00] um, I'm looking forward to having that one on display again very soon.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, that is such a beautiful piece. Just really gorgeous just to look at. And I like the way that piece is framed too, with the kind of old sort of gold, right? Isn't it a gold kind of,

Maddie Blonquist: yeah. It's like a period frame. Frame as well for this.

Jenny Champoux: yeah. In that triptych three panel

Maddie Blonquist: Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: but then with a totally different kind of visual inside of the frame than what you might expect to see in a frame like that. And that's a, a really cool juxtaposition and, um, like you said, just helps you, helps you think about things a little differently.

Well, Chase and Maddie, thanks for all the great curatorial work that you're both doing, and thanks for an enlightening discussion today.

Maddie Blonquist: Thank you. This was really fun.

Chase Westfall: Thanks for the time. Thanks to both of you and yeah, wonderful discussion and appreciate that you know, you guys are building audience for this kind of conversation. It's important.

Jenny Champoux: Thanks. [01:16:00] To our listeners, thanks for tuning in. Join us next time for our final episode of this series where we'll be joined by Emily Larsen Booth and Micah Christensen. We'll see you then.

Thank you for listening to Latter-day Saint Art, a Wayfare Magazine limited series podcast. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. I hope you'll order a copy of the book to read the full essays and see all the gorgeous full-color images of the artwork.

You can learn more about the book and other projects at the Center's website at centerforlatterdaysaintarts.org. If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to listen to the other episodes in this series. You can subscribe to Wayfare Magazine at wayfaremagazine.org. And thanks to our sponsor, Faith Matters, an organization that promotes an expansive view of the Restored gospel.

If you'd like to learn more about Latter-Day Saint art, check out my [01:17:00] other podcast, Behold: Conversations on Book of Mormon Art. You can also learn more at my website, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. With more than 11,000 artworks, it's the largest public digital database of Latter-day Saint art. You can search by scripture reference topic, artist, country, year and more.

And we recently added a new section for art based on Church history, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. The website is bookofmormonartcatalog.org. Check it out and see what exciting new art you can find to enrich your study.

Jennifer Champoux is the founder and director of the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. She wrote C. C. A. Christensen: A Mormon Visionary (University of Illinois Press, forthcoming) and co-edited Approaching the Tree: Interpreting 1 Nephi 8 (Maxwell Institute, 2023).