Jenny Champoux: Hello and welcome back to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux. In Latter-day Saint Art, I'll guide you through an examination of the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts.

Please note that a transcript of each episode, along with the images we discuss, is available at Wayfaremagazine.org.

In this episode, we'll consider questions of geography and culture in the art, particularly as it relates to Latter-day Saints in Utah and Mexico. We'll look at how members of the Church reshaped landscape, built architecture, and then projected an image of their space through the art.

Our guest scholars will also teach us about the dynamic interweaving of cultures in the art, and how Latter-day Saints have wrestled with combining faith and art making. Our [00:01:00] guests today are Heather Belnap, James Swensen, and Rebecca Janzen.

Heather Belnap is a professor of Art History and Curatorial Studies and a Global Women's Studies affiliate at Brigham Young University. She presents and publishes widely in feminist and cultural history, including the fields of Utah and Mormon studies. Recent publications in these areas include the book Marianne Meets the Mormons: Representations of Mormonism in Nineteenth Century France and a special issue for the Utah Historical Quarterly on Utah women in the arts at mid-century. She is currently working on a biography of Minerva Teichert and a book project on Utah women in the arts. Her chapter in the Latter-day Saint art book is, “Globetrotting Mormon Women Artists and the Art of Travel, 1900 to 1950.”

James Swensen is a professor of art history and the history of photography at BYU. He is the author of Picturing Migrants: The Grapes of Wrath and New Deal Documentary Photography. And also, In a Rugged Land: Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and the Three Mormon Towns Collaboration. His chapter in the Oxford volume is, “Defining the Mormon Landscape: Photography, and the Representation and Evolution of a Distinctive American Space.”

And then Rebecca Janzen is a professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. She is a scholar of gender, disability, and religious studies in Mexican literature and culture, whose research focuses on excluded populations in Mexico. Her most recent book, Unlawful Violence: Law and Cultural Production in 21st Century Mexico, is about human rights, law, and literature. Her essay that we'll discuss today is titled, “Mormon Art and Architecture in Mexico: Between Mexico and the United States.”

If you're following along at home with the book, you'll notice that we're not moving [00:03:00] chapter by chapter in these episodes. Instead, I've grouped the authors in ways that will highlight themes or that I think will create interesting dialogue.

I'm really looking forward to talking with our three brilliant guests today. So, let's get into it.

Heather, Rebecca, James. Thank you for talking with us today.

Heather Belnap: Great to be here.

James Swensen: Glad to be with you.

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah. Thanks for having us.

Jenny Champoux: Thank you. I've given our listeners a little short introduction to your scholarship, but I want to give you each a chance to tell us more about your work. Heather, I want to start with you. I've known you for a long time, since I was an undergraduate at BYU and took a class from you. And you just had a way of making the art and the history come alive. And you really helped me learn to look more closely and more critically at art. And so I was thrilled to read your chapter and see still, I'm still learning from you that way, from the great work you're doing.

And I really appreciate your [00:04:00] attention in this book and so much of your work, to highlighting the experiences and contributions of women artists. I know you recently helped curate the Work & Wonder exhibition at the Church History Museum, and I just wanted to ask, in what ways did you hope viewers would come away from that exhibition better informed about Latter-day Saint women artists?

Heather Belnap: Yeah, so as you know, first of all, thank you. You are a credit to the profession and, just having had students like you makes kind of all the difference. And as you know, most of my research and publication has been on women artists and critics and patrons, just kind of sort of women in the arts.

And that's something I hold really near and dear. In turning the lens to Latter-day Saint art, I was particularly keen on making sure that people knew about the [00:05:00] contributions of women. And part of that was expanding what I think a lot of people have in terms of their definition of what is art. So, as you go through the exhibition, you will see a lot of material with objects, right? Things that have been considered craft. Everything’s material. This an exhibition, but I'm talking about textiles and pottery, and the like, and those media and genres have been, as you know, overlooked for, for a long time in the annals of art history.

And I think that's especially true actually in Latter-day Saint arts. So, that was important to highlight that women artists sometimes use nontraditional media.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, thank you. I think that is really important to have that broader sense of what we consider art or the visual culture. Yeah, thank you. Okay. And then Rebecca, your work often draws [00:06:00] on literature in considering Mexican culture. I just wondered, do you find that the tools you use in literary analysis are also helpful in considering material and visual culture?

Rebecca Janzen: I do think that. My PhD is in Spanish in the study of Mexican literature. So that's what I was trained in, in critical cultural theory and thinking about how we can use those.

So I was trained in the study of literature, like close reading, a text in its historical context, and in conversation with critical and cultural theory. And, I think that these tools are really useful for analyzing anything that you could ever want to analyze.

And when I first started working on or expanding what I had already written about Mexico in a subsequent project, which was about Mennonites and later on Mormons, including members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I needed to [00:07:00] look for sources that were not literary because there weren't things in literary sources.

So I see this chapter as expanding a little bit of what I had done in that previous work.

I’ll add one anecdote. Amanda Beardsley was assigned to edit my section and many of her comments were encouraging me to pay closer attention to the visual elements. So I was really thankful for the expertise of an art historian to help me think about art as also art and also material culture as art.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I think that's great. It's always nice when you can get a little cross disciplinary action going and just kind of open up new avenues for thinking about things. So yeah, thank you. And then, James, I know you're a scholar of art history and photography history, and your chapter mostly, I think, maybe exclusively focuses on photographs. Just to help our listeners who maybe aren't as familiar with [00:08:00] photography studies, can you tell us, do viewers tend to respond differently to photographs than to paintings? Or do you as a scholar read a photograph differently than a painting?

James Swensen: That's a great question, and thanks for having us on. I think we react to photography differently, and yet one of the things that I really love is, in so many ways, as you can read a painting, you can read a photograph. And, you know, it is a little different, obviously. I mean, with a photograph, there's always a there, there.

I mean, we can always assume that. At some point in time, that thing really did exist. And so in that sense, I think we trust photographs. What I really love is artists who against that or go with that. So, yeah, I've always loved photography in that sense in that it really does enable you to encapsulate time, but also to see it, to read it, and to think [00:09:00] about what images do and how they act and what they can be. And so in that sense, it's a lot like painting in that, you know, you can really read into them and spend a lot of time actually exploring what a photograph, just like a painting, what it is.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I loved reading your chapter because it helped, I think it modeled that kind of, engagement with photography.

So, I want to focus our discussion today around three themes that I saw that emerged from your three chapters when I read them together. First, shaping space through art. Second, interweaving cultures in the art. And then, finally, combining faith and art making.

First, each of your essays spoke to this Latter-day Saint desire to shape a distinctive space. Maybe that's an actual literal geographical space, like in Salt Lake City, or it might be a domestic space or more of a more nebulous cultural space. Heather, let me go to you first. [00:10:00] Your essay starts with a consideration of Mary Teasdel's Mother and Child, which I know you also included in that Work & Wonder exhibition. I loved being able to see that there. So compositionally, this piece juxtaposes interior and exterior space in a pretty dramatic way. Can you tell us more about this artist and the kind of spaces she was carving out with this?

Heather Belnap: Sure. And so Mary Teasdel is often, you know, talked about as the first, Latter-day Saint woman to go abroad to Paris to study and train and then come back and apply the lessons that she had learned there. So this painting, it shows a mother holding a young baby, might be a nurse actually, but who knows?

Right. Anyway, but, but it's come down to us as mother and child and she is seated at a window. She's looking outside through these diaphanous curtains to clearly a quaint French village. You can just tell from the architecture [00:11:00] that is there. But Mary was very astute in that the work that she created, for audiences back home, sort of brought together the French traditions and even some French subjects, but they were ones that could translate meaningfully to those who are part of the largely Latter-day Saint community in Utah. And so that scene of domesticity, but it is domesticity that is welcoming a connection to the exterior world and to sites and spaces beyond. You know, beautifully painted in all of the latest styles that were being taught in Paris. You know, but again, with the kind of tone and mood and subject matter that would resonate with locals.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I was really fascinated in your discussion of how she was bringing those French elements back to Utah and [00:12:00] then combining it with Utah spaces and culture.

And then for Becca, just to totally shift gears and move to Mexico here. In your chapter, you compared two early 20th century photographs of the Monroy family that reveal the ways that Mexican saints sought to create a new cultural space that was blending their traditional culture with their commitment to this modern American-based religion, which was just fascinating. Can you talk to us more about how you see that tension reflected in these two family photographs?

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah, Mexico is actually not as far away from this Parisian art as you might think because France was so influential on Mexico after its independence, which is in the earliest part of the 19th century and particularly influenced in the 19th century constitution of Mexico. And now the part that it relates to these photographs in the later, [00:13:00] the very last years of the 19th century, and first decade of the 20th century, the Mexican president, Porfirio Díaz, wanted to modernize the country.

And this is kind of a shift in looking to France for ideas to the U.S. And with railways and all kinds of things that modernize countries at that time. And then there's a revolution that dramatically changes the country and imposes mandatory secularism and takes away a lot of power from the Catholic church.

And some of the leaders who were imposing this mandatory secularism, looked very favorably upon Protestantism. And then there was The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that, of course had been in Mexico for a long time. But in the more central part of Mexico, where this family was living in Mexico State, these are some of the earliest saints in Mexico.

And, I had read about them really briefly in some histories of the Church in Mexico, but then to actually, like, see their faces [00:14:00] and in the context of their official biographies, and some stories by their descendants, it's just incredible because they're in these, like, profile pictures that you might, I think they're called carte de visite in French, that you could send to other people, that were given to the mission president's wife, and who I believe have been very important to them.

And you can see things in their clothes and in how they're posing that in some ways are similar to European or US styles. And then in other ways are maintaining some more traditional Mexican ideas, but it's in this context of so much change happening in Mexico, with like, how are we going to be like this modern nation? Plus, okay, now we've joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Like what is that going to look like? And how is that going to let these two people claim their identities? So, in one of them, Jesús Mera de Monroy, she is, I'm just looking at the picture now, [00:15:00] like, it's, has like a little pin at her neck, like in a Victorian style, and then some, like, what is this word, ruffles, I guess, and in some ways this evokes traditional Indigenous clothing, but then there is like the neck and the sleeves evoke other styles, and then she's wearing a cross, which at that time was really not worn by Church members, so this is definitely referring back to her Catholic background.

So all of these things are converging in one photograph that we receive in the archives from the Church and by looking at it closely and in this historical context you can see all kinds of things that are happening, but that are also having a real impact on a real person. So I just think they're really cool.

And there's a lot about this family, so you can see them in different contexts, in different situations. But, going back to what James was saying about photographs, like, it did really happen, but also [00:16:00] what were all of the things around it that made it look like this? And what can that tell us?

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, Rebecca, I just, it was just amazing reading your analysis of these two photographs, which at first glance just looked like a couple of old family photographs. And then you were able to pull all of this context and history and complicated cultural negotiations that, you see just by looking at what they're wearing and how they're posed and what's the style of the, the card. Just, yeah, really interesting, that tradition and modernity kind of brought together in these photographs.

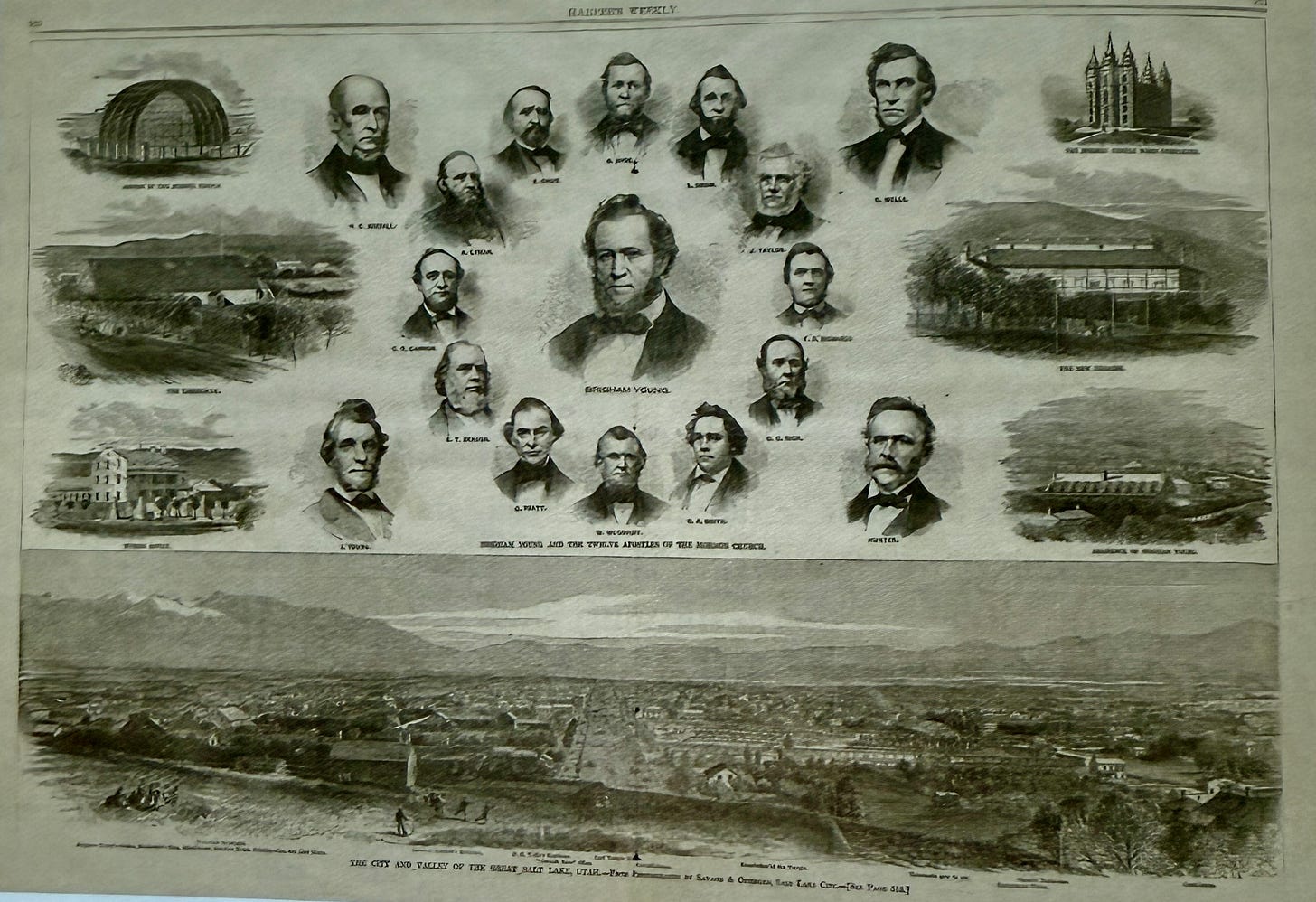

And then, James, to continue with photos, your discussion of Savage's photo of the Great Salt Lake City panorama was another great example of how early Latter-day Saints were shaping the geography in Utah and then projecting it to the world through these images. So tell us about how does this image work to shape [00:17:00] space?

James Swensen: Well, can I say one thing first? So like Rebecca mentioned, carte de visites and just how these two great photographs and Savage, who you mentioned was producing these by the hundreds. It's, in fact, my wife's family ended up down in the colonies and they came out with Charles Savage’s carte de visites too.

So this connection that you can make here, it's really great. And how I love that how photographs describe it, they can't explain. And just looking at, I'm just looking at those two photographs right now, Rebecca, and how great they are and just all the stuff that you can get out of them. And, and to that point, with Savage.

So Savage made it out to Utah in 1860. And so his photograph of, so he makes a photograph of Salt Lake Valley, but he makes it as a panorama, which he takes three or four shots looking straight down, you know, one of the avenues actually what is now State Street and creates this panorama that is then picked up by Harper's Weekly. And so this image of the Salt Lake Valley and the [00:18:00] growth of the city, but also the dramatic landscape is featured there. And what I really love is when Harper's publishes that they need to make sense of it, right? So they write of how the Saints are turning or making the desert bloom as a rose, which obviously has biblical prophecy and this idea that here we are, we're making this landscape or changing it, we're transforming it into this thing where, you know, we're literally taking a desert and now making it into farms and a prosperous city. And if you look at Savage's photograph, it's great because, and even the Harper’s, because you can see literally the city rising up and filling the northern end of the valley and facing south, right? That at one point they're going to fill not just the Intermountain West, but continue down to Rebecca's point all the way down to Mexico.

And there's just no end to what the Saints can do. And Savage was a believer, right? He wanted to use his work [00:19:00] as a way of projecting who the Saints are and the great things they were doing out in the American West. So it's a really great example. And when it showed up in Harper's, not only did it have the Salt Lake Valley, but it had an image of Brigham Young, had image of the 12 apostles, had an image of the tabernacle, which was then being built. And some of the other things that the Saints were doing in, you know, the Salt Lake Valley. And so it was just this, this real opportunity for a national audience to show what, Brigham Young in the center of this constellation, what he was, what was happening out in the American West.

Jenny Champoux: I know this was 19th century, can you remind me of the date?

James Swensen: Yeah, so the Harper's shows up in 1866.

Jenny Champoux: well,

James Swensen: Harper's Weekly.

Jenny Champoux: yeah.

James Swensen: So, he probably made the photographs either 1864, 1865, and then they would have transformed to woodblock print, which made it possible to show up in [00:20:00] Harper's.

Jenny Champoux: Right. And you mentioned in your chapter, also pointed out who is left out of this image of the Salt Lake Valley.

James Swensen: Yeah, we need to remember that this territory was not theirs, and so this is an act of colonization, and that for centuries, the Shoshone and Utes, in particular, had been using, had been basically, Salt Lake Valley and especially Utah County, in and around Utah Lake was one of their most important cultural centers and had been for centuries.

And so, interesting enough, when you look at the Savage Photographs, you're not going to see the presence of Native Americans, and in essence, right, that this was new land, right, and, this land that was open for the taking of the Saints. That clearly is there as well.

Jenny Champoux: Let's jump now from 19th century photographs to 21st century. And James, we're going to move into our second theme [00:21:00] here about this interweaving of cultures. Savage's photograph that you just talked about really leaned into this distinctly Mormon aspect of the landscape with the image of Brigham Young above it and everything. But then in the 21st century, you talk about some artists, including Christine Armbruster.

James Swensen: Armbruster? Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: She situates her rural Utah scenes as part of a broader contemporary American portrait. How do her photographs put American and Mormon elements into conversation?

James Swensen: Well what I love about Christine's project is one is actually started when she was a student of mine here at Brigham Young University and she received a grant to go out and photograph towns in Utah that were 800 inhabitants and less so that was the, that was the basic parameter of what she was going to do.

And so she went out photographing these small little Utah towns. What's really great about it is in some ways these towns do maintain in Christine's photographs some of [00:22:00] their Mormon identity. By and large, they show larger trends. For example, an immigrant, at a restaurant, right? That, again, a different sense of who is here, what the West has become. Yeah, those earlier elements are there, but this real Americanization that you see of the American West that, you know, she's photographing an old couple, it's in Escalante, you know, he's drinking a Pepsi, she's drinking a Coke. And so almost to that Warhol, like they were all drinking the same things, we're all doing the same things. And so with Christine's work, it's really great because she didn't set out to necessarily make a portrait of a Mormon landscape. But what she revealed was how the Mormon landscape had increasingly become similar to almost any other landscape in the American West or an American landscape. And so I really like how she was able to kind of walk that interesting line and, and show those two things in conversation with them, with each other.

Jenny Champoux: [00:23:00] Rebecca, I was really intrigued by your discussion of 20th century church buildings in Mexico and the way their design reflected this weaving of cultures. Tell us more about that built space.

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah, I was also intrigued by them, evidently, and I think that they show us certain trends that are unique to Mormons or to Mexico, but going off of what James was just saying, like, studying a small group of people can also show you these broader trends that are happening, and in the case of these church buildings, they are, speaking to architectural trends that are popular in the U.S. So, what I was thinking about, trying to do in the chapter is move from earlier part of the 20th century, late 19th century, and then through the middle part of the 20th century, the best art that I could find were photographs in the archives, and they were primarily of buildings. [00:24:00] There were some of people, of course, but the more telling ones, and they were very much what we have in our minds from the United States, an idea of what Mexico should look like.

So it's Spanish colonial revival. If any of your listeners are familiar with San Diego, like the area around the zoo is very much in that spirit. And this is not like in California or in Mexico from the Spanish colonizers. It's from the 20th century. And realizing that was, it's kind of surprising to me, and then that the U.S.-based Church was bringing their idea of Spain to Mexico, and I conjecture that it's perhaps because they thought, “oh, Mexico, that's like Spain. So we'll provide something that's like where you're from, kind of.” You can see these [00:25:00] buildings, I primarily noted this in the roofs, like the red tile roofs and, like the arches that you might see, and there are some photographs from southern Mexico, where you can also see the inside. And I was thinking there, that it's possible that this was reusing another space that had been previously used in Mexico, because so which church, Catholic Church property was expropriated in the middle of the 19th century, and again, in the early part of the 20th century, there are a lot of buildings that were formerly convents, formerly churches, formerly something Catholic, that are used for other things, sometimes hotels, sometimes government buildings, sometimes libraries that are publicly owned and operated.

So I'm not sure that the photographs are that, but this is something that is so common, it's possible that they are in fact an old building, and not [00:26:00] necessarily, you know just what people in the United States thought they should do in Mexico. But thinking about all of these different influences on the group of people who joined, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or whose children remained in the Church and were engaged in all these activities, like you can see in one of the pictures a bunch of kids, and that these became spaces for meaning and that, yeah, that were really significant for people, who were trying to navigate this new identity for themselves, but in the midst of all of these strange conglomeration of influences.

Jenny Champoux: So in the early 20th century, we have people in Mexico joining The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. And then you have, and then they need a [00:27:00] building space. So you have members of the church that are Americans, probably in Utah, designing these spaces to be built in Mexico, they're designing it with what seems like Mexican styling to them, but you're saying that actually didn't, it wasn't actually Mexican and it may be, I'm just curious, did the members in Mexico when they were starting to attend meetings at these new buildings, did they look at the buildings and think of them as more American than Mexican?

Rebecca Janzen: I don't know. There are really great recorded interviews with people, like oral histories, but it's primarily the story of someone's faith. So like when they joined the church, or when they got married, or when there was a temple that was close enough that they could actually go to, that kind of thing, which is really nice in some ways, but I'm like, but I want to know, like, what happened when this major historical event happened?

Like, how did that affect you? Did your community come together? Like after there was a big earthquake? I [00:28:00] don't know. I'm guessing that the answer is yes, but that's not perceived as part of, you know, the story that they're telling to the person who's collecting this oral history. I think that because these buildings are so different from a Catholic church, and like a Catholic church in Mexico is also different from a Catholic church in the United States. It is extremely ornate, like much more gold plated everything. And you will see many more images and statues of significant religious figures than you would probably see in a Catholic church in the US unless it was predominantly used for Latino people and particularly masses in Spanish.

So I think that they would have said, okay, like we're joining this American church. Of course it's going to look different. And other Protestant church buildings, which predates some of them also have some of these elements, but more closely mirror the denominations in the United States. I'm seeing that I've only seen the exteriors, [00:29:00] but like of Lutheran churches in Mexico or Episcopalian or Methodist.

And now of course, all of the buildings have a more uniform look. So if I have been able to talk to people or attend with them, it's, The questions that would come up are just like, oh, well, this is what the standard building looks like. Like, so I know no matter where I am in the world, like what I'm doing, which is a different message.

And, and it's a different time. So I don't know.

James Swensen: Can I ask, so I really love, in fact, looking at these photographs of these chapels, now there's a time where they try to blend in and trying to blend in, they're actually standing out more, but also to that point, and Paul Starrs, the geographer, mentions like he knows exactly when he's traveling through Mormon country because he sees that distinctive LDS chapel that looks like no other. Like churches in the West or beyond that. And just how that instantly reminds him of where he is. And, and we all know kind of thinking about what these chapels look like, exactly what they look like, exactly what kind of [00:30:00] carpet they have, wainscoting. I mean, all the things, right. That becomes like the standard LDS chapel type. So I love it. I can't almost win either way with this.

Jenny Champoux: Heather, you were also looking at the early 20th century, but focusing more on American women artists that were Latter-day Saints, and you explained how they suddenly had this ability to travel internationally in a way that women really never had before. How did that newfound ability to travel affect Utah or Latter-day Saint art and culture?

Heather Belnap: Yeah, I mean, that was your travel was critical. That's sort of the argument of the essay is that in order to be considered a professional artist, which is what the women that I highlighted wanted to be considered, you had to travel abroad. Ideally, you trained abroad as well. initially that would happen back East and in Europe. And then you would go and travel hopefully beyond. What I see is a larger opening up of just the opportunity for travel for people, period. It becomes more affordable, it becomes faster, it becomes safer, just all of these things. So we see these young women moving beyond the East coast and Europe, going into the Holy Land, going into Central and South America, all over the world actually.

And that becomes a really important element to their, training and to their education, but also to their legitimacy as these artists who are worldly. So, two of the artists that I focused on, Minerva Teichert and Verla Birrell, both spent considerable time in Central and South America as part of that, their enterprise of becoming globetrotters and [00:32:00] expanding kind of definitions of what it meant to be a Mormon woman and to make Latter-day Saint art.

Jenny Champoux: So expanding both the art canon and the definitions of Mormon womanhood.

Heather Belnap: And I was thinking as, Rebecca and then James were talking about these churches that were, that were down in Mexico, Minerva spent the two trips and one was a kind of study abroad with her daughter who was at school, University of California. Mexico and Mexico City. So there for several weeks at a time and then spends two months in South America.

And not once does she record going to church in her letters, which, you know, at least the ones that are extant and, and, you know, been kept and the like. But she spoke an awful lot about the architecture that she was seeing elsewhere, and it may have just been, you know, sort of no comment.

I'm sure she went to church when she could. I'm sure [00:33:00] she, you know, entered into those spaces. But it may felt it have felt a little bit, yeah, too familiar, right? And not the sort of thing that she wanted to record for posterity.

Jenny Champoux: I loved how you talked about the ways Minerva, in her travels in Latin America, looked to architecture or indigenous costuming or even like the flora and fauna of the area and incorporated that into her Book of Mormon paintings. Can you give us an example of how she's doing that?

Heather Belnap: Yeah. Well, she did a lot of preparatory work too. So, she always dreamed of traveling and when she couldn't, she spent her money with National Geographic magazines and other kinds of, just kind of visual cultures so that she could become acquainted with that. And then as she is able to travel the forties, and in the fifties, you know, she is doing sketches of these new architectural sites and of the various costumes.

She's [00:34:00] writing about the various colors that she's seeing there. And you can tell that, you know, she's trying to preserve this because she has this ambition to do a suite of Book of Mormon paintings that will be, anthropologically, architecturally accurate or authentic. And as we know, this is part of a broader movement that happens in the mid 20th century with this idea of Book of Mormon archaeology and both Minerva Teichert and Verla Birrell are part of that, you know, of that, of that moment of being interested in authenticity and, Mabel Frazer is another one.

I should mention her. I don't want to leave her out. That spent quite a bit of time down there and she would actually go and measure and of the sites. And, because she used that particular, sacred sites she used as a backdrop in her Christ among the Nephites painting. And she wanted to [00:35:00] have all of the dimensions and proportions and scale and so on correct. So I think that's also a part of adding to that, legitimacy, right? And, and that this is not just from descriptions. This is not just from things that have been seen in books, but this is from lived reality and being really conscientious about trying to translate that and transmit that in their art.

Jenny Champoux: Okay, so the final theme I want to think about is the intersections of faith and art. And Heather, you explained that some of these women artists felt compelled to focus on Latter-day Saint or subjects in their art, and others felt more free to explore other subjects. And yet, it seems that all of them felt their artistic careers and their spiritual faith were compatible. Was this a change in attitude from the prior generation? Was this new for this group of women or was there a shift going on? And can you give us an example of [00:36:00] woman artist that felt like she could tackle subjects outside of religion?

Heather Belnap: Yeah. So, for the first generation or wave of women artists, and this is primarily during the progressive era, so 1890, 1920, 1930, where, this whole idea of having separate spheres or separate kind of lives just was very foreign, right, to Latter-day Saints, and especially to Latter-day Saint women, where it was: my faith, my profession, my family, my citizenship, all of that comes together. And there is no sort of separation, right?

I was thinking around here. I've got several family members that are into this film Severance where you split your home life with your work life with this idea that it can make life easier or something. They lived unsevered lives where this was [00:37:00] everything that they did was for the building of the house of the kingdom of God. And so you see that with that first wave of artists, of Rose Hartwell and of Mary Teasdel, and others, who really take this idea that they have a mission. And it's the Gospel of Beauty is what Alice Merrill Horne calls and that they have been called to do this work. And they recognize the need to go abroad, as I said, to study and train and the like. But with the second generation or second wave of artists, Minerva is sort of on the cusp of the first and the second. I mean, she sort of occupies both places, but Minerva, Mabel Frazer, Verla Birrell, they all want to be taken very seriously as artists and artists who are going to do subjects that are associated with the Church and with Mormon culture. But also maybe with just the American West, or, you know, sites that they see as, as they are, are [00:38:00] traveling. And, and so, that kind of confidence to kind of move out, I guess, from that subject matter, came in part because they saw themselves as part of a larger art world and a larger, market, you know, and the fact of the matter was there wasn't a lot of patronage for artists in the Church. There were some temple murals. There would be, you know, occasional illustrations that would go into Church manuals and, and, and, and the like, or inclusion in some of the auxiliary publications. But, but by and large, you know, these were artists who needed to make a living. And so they're going to, you know, be expanding purview of, of the art, what constituted the art world and the art market and subjects that would be commercially viable.

Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I really appreciated that discussion, because I feel like, as a member of the church, I'm pretty familiar with, you know, Minerva Teichert's [00:39:00] work, or even Mabel Frazer, but then some of the others you mentioned that were less focused on scripture but we're more just these scenes of a little village in Mexico or somewhere where they had traveled and, these beautiful, just unromanticized, very realistic, but, but gorgeous and dynamic scenes of their travels.

And that was a side of it that I hadn't really seen that artwork before.

Heather Belnap: Yeah. Yeah. And again, you're, you're referencing the works of Verla, Verla Birrell, you know, she wanted a national stage. She self-published a couple of books, including one on textiles that got picked up, eventually by a publisher back in New York and is still circulation, uh, these, this book on textile arts.

And so part of uh, kind of the subtext, I guess, of her career was also mainstreaming what Latter-day Saint artists doing, who they were, their [00:40:00] interests, you know, and again, thinking about kind of broader communities.

Jenny Champoux: So, James, continuing this theme of art production and faith, I loved in your chapter the way you compared three, well, you compared several photographs of the Manti Temple, and three of them, I thought, really made a fascinating comparison. George Edward Anderson, Midgley, and Daniel George, which I guess they also all have the name George somewhere…

James Swensen: iIt's making it as confusing as possible. Yes.

Jenny Champoux: But I mean, these artists were all drawing on their faith and culture, but in really different ways in these photographs. Will you walk us through them?

James Swensen: Yeah. Can I say one thing? Verla Birrell grew up down the street for me. And I'm sorry, I grew up up the street from Verla Birrell. Let me put this the right way. And so I regret nothing. Like, why did my mom knew her? In fact, I was talking with my mom. And I'm like, I wish I would have known questions to ask as you know, as a 12 year old boy.

Heather Belnap: James, I had [00:41:00] no idea.

James Swensen: I didn't either actually Heather. So I'm just telling you this now. All the things I wish I would have been able to ask at the time. Sorry, to your question though, Jenny, Yeah, there's actually four images of the, of the temple, but you're right, three from Georges. George Anderson, George Midgley, and, Daniel George.

But there's also a good old Ansel Adams thrown in there for good measure. And, you know, it was nice when I was thinking about this chapter and this topic, that it really became an opportunity for me. The Manti Temple became like a leitmotif, like an opportunity for me to really look at how we photographed it differently from one century, actually three centuries, basically, the 19th, the 20th and the 21st century, and how it stood as the symbol, but also this opportunity to capture what it is we think about it, about the landscape that surrounds it.

So, yeah, so you mentioned George Anderson's the first, right. And, and he was actually the first person I think [00:42:00] married in the Manti Temple. So he has this personal connection you see in his work and he makes hundreds, thousands of photographs that, that are still extant you can literally just see him returning to this site over and over again, almost like a pilgrimage to photograph. The temple as it's starting to rise up right out of this landscape and become this, this symbol, right? Literally on a hill.

And then George Midgley, who was the, the son in law of Heber J. Grant through a pictorial style. So it's soft and hazy, right? A style that's very popular at the turn the century, but well into the mid 20th century in Utah for him, it's about nostalgia, right This aspect of Utah life that is slowly starting to slip away. I mean, shepherds and sheep being replaced with automobiles and all the other thing.

And I do have to put in a plug for Ansel Adams because you're right. If it's about belief, Ansel Adams is not a member of the Church. I'm not saying that, but he has a [00:43:00] definite belief in modernism and that's, that's so different from the others that are photographing this and this idea that it's, it's, yes, it's just this beautiful thing.

It's about harmony and form and pattern, and that you can find these things, even in, you know, the middle of nowhere, right, in Utah. So, I really love that contrast, especially between the Midgley and the Ansel Adams, where it's, you see two very different ways of photographing the exact same thing and how they're steeped in meaning but in really disparate opposite ways.

And then the last image is an image I love. Daniel George is a young photographer. He's now here at BYU and he did a series called God Go West. And he comes to Manti, but not just to photograph the temple, but for those of you who haven't seen it, he's actually photographing all the chairs that are set up for the Manti pageant. You know, pageantry is obviously such an important part of [00:44:00] the visual culture and the culture of what we do. And, and yet slipping away, I think this was the Manti Temple pageant. I think this was the second to last year, something like that. And so here we have these empty seats that are set up and Daniel George reacting against earlier photographic styles.

He's reacting against things like Ansel Adams. He wants to show culture. He doesn't want things to seem as idyllic or as perfect. And yet at the same time, he's showing us this other way in which this temple is not just a symbol, but a backdrop for our belief and these empty chairs. I love them because they're, they're very, almost symbolic of all the people that are going to fill them.

And, and yet it's a very realistic view of what just a Mormon landscape looks like, but really the Mormon experience, because if you've been involved with the Mormon experience, you know, you're setting up a lot of chairs and taking down a lot of chairs. And so that's a part of, that's part of it too.

And, and so for Daniel to capture all those things in a very tongue in cheek, yeah, if you're, [00:45:00] you're supposed to laugh, you're supposed to kind of chuckle at all these empty seats and the fake rocks on the hillside and Manti Temple seemingly kind of rising up above all this. So yeah, Manti was, uh, that really was the thing that helped me link all these things together from one century through another and ending up in the 21st century.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, it was brilliant. And I think, I think these three, if I could just focus on the three Georges for a second, as much as I love Ansel Adams too. But I think those three, because they were all members of the Church, I think, I think reflects something about Latter-day Saint identity and its evolution over time, where you have Anderson in the 19th century and an emphasis on, right, this incredible structure rising up out of the desert and the idea that it's done through the hard work of the Saints. And then 20th century, you've gone on to a [00:46:00] generation or two removed from the early pioneers settlers and you've got Midgley with that more nostalgic looking back to those early days. And then with Daniel George in the 21st century, it's kind of a postmodern, like you said, tongue in cheek, self-reflective and critical play with our identity.

So I just think there's something really interesting there about what it says on that evolution.

James Swensen: Yeah, Daniel George employs what's called a New Topographics approach. Topographics has been popular landscape photography in the West since the 70s. And it's this real reaction of, of not showing an idyllic West, but a very realistic West. A sense of what this place is, how it looks, how culture and how other forces have impacted this place. And yeah, Daniel George does a great job on this. And, and photograph of the Manti Temple is one of my favorites. I mean, it just, it makes me chuckle every time I see it. And every time I look at it, there's always something else I can learn from [00:47:00] it.

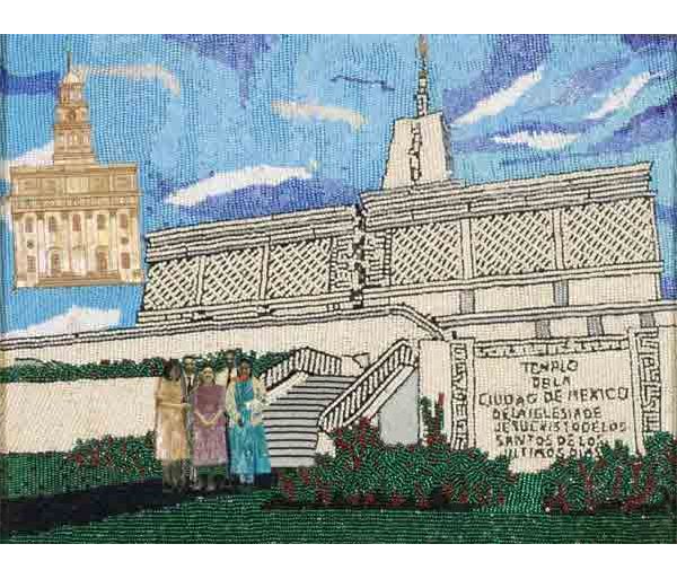

Jenny Champoux: Okay. I'll go back and take a closer look at that one again. And Rebecca, let's, I want to come to you too, to think about this idea of cultural negotiation and thinking about art and faith and, uh, one of the works you pointed to was by Blanca Estella Pavón Martínez, from 2002. It's called Earthly Symbol of a Spiritual Reality. I thought this was a great example you included of how saints in Mexico are dealing with tensions and cultural negotiation and, and framing their faith and culture in the art.

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah, I was really happy that in the part of the chapter where I talked about more recent events that there was art that was produced by Church members and who were named, like I'm assuming that some Church members were taking some of the pictures that I included that weren't like the more formal portraits, but we don't know who they were.

And so this is [00:48:00] a person, Blanca Estella Pavón de Martínez, who entered this work in one of the art competitions, which are part of some of the other chapters in the book. And we see so much about Mexico and about the Church. This is the kind of work that I would love to be able to run my hand on because you can just see the texture.

Some of it is clearly beaded, but there's definitely things happening with textiles in it. And most of it is the Mexico City Temple and then there is a group of people that are like, looks like a photograph that is tacked onto it. And also an image of the Nauvoo Temple, which is harkening back to an even earlier part of the Church's history, and to see how this is kind of a continuum from mid 19th century onwards, and then the Mexico City Temple has Mayan revival art in its style.

So [00:49:00] it's an idea of indigenous people, which is very much in keeping with the Mexican government's idea and use of indigenous symbolism, which is to say, ignoring particular languages and cultures in favor of a global indigenous identity that the government relates to in ways that are problematic and different than the ways that, for example, the United States government relates to indigenous nations, which are problematic for different reasons.

And so this gets incorporated into the art. And of course, it's an important part of the restored gospel. And so that's really important for Church members in Mexico to see yourself in this text, where that, especially for people who join the church, like that wasn't part of, for example, their experience as Catholics.

And so, you know, in spite of my criticisms of this architectural style, that it's a way that people feel so included and so part of this broader group. And that's what this person put in her artwork, like there's the family in front of it. [00:50:00] So of course that is also important. And either about to go in or leaving, that's unclear, but to me it's aesthetically pleasing and also there's so many interesting layers of history and culture and art all within this work that's in the Church History Museum.

James Swensen: But I think it's almost interesting that, it would almost make more sense if it was Salt Lake Temple, right?

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah,

James Swensen: and literally how it kind of floats there in the sky as this thing, I mean, it really is as I'm looking at it right now, I'm like, that's really interesting.

And why wouldn't it be Salt Lake, which would have more of a direct connection? Why are you hearkening back at this point to a temple that doesn't, well, from earlier Church history that's being rebuilt, or maybe not even rebuilt at that point. I'm sorry. I don't remember. But like, that's, it's really interesting why that one I'd be curious to know.

Jenny Champoux: I feel like it was around 2002

James Swensen: It's, is that maybe [00:51:00] that's in this conversation.

Jenny Champoux: that the Nauvoo Temple was rededicated.

James Swensen: with President Hinckley and maybe it's in the discussion. Maybe, maybe that's why it's showing up.

Jenny Champoux: yeah.

James Swensen: It is interesting.

Rebecca Janzen: that would make sense. Like, the artwork is from 2002, but usually that means that the art was made before then. So I guess it was, yeah, just in whatever this person was hearing at whatever they were doing, but like in general conference talks or something. But It's really not something that any Mexican church member I know of has ever talked about, um, unless they've had missionaries from Missouri, which has not been what I've observed.

James Swensen: Okay. So it was, it was completed and dedicated in 2002. So that makes sense then that they're like,

Rebecca Janzen: Mm hmm.

James Swensen: what I'm talking about. I've been cheating, but like, so it is in the, it's in the kind of the ether that literally in the ether,

Rebecca Janzen: Mm hmm.

James Swensen: Yeah. I think it's really [00:52:00] cool.

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: Your discussion here is, is making me think about what you were saying earlier too, about the early 20th century Church meetinghouse buildings and, and just this tension between native elements,

Rebecca Janzen: Mm hmm.

Jenny Champoux: and the U. S. elements and maybe even the Mexican members seeing themselves through that U.S. lens. way, like not even seeing themselves as they see themselves, but the way they think they're being seen. Right. I think you touched on this in your chapter, right?

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah, I think there's just so many layers. This is my casual observation, that many people in the United States would perceive most people in Mexico as being Indigenous or Native, when that's not how people in Mexico would identify themselves. The [00:53:00] national discourse is a discourse of mestizaje, or like everyone after the Mexican Revolution in 1917, there was this mandatory discourse, people weren't Indigenous anymore, they were going to be mestizo.

So people look exactly the same but this is a like state-imposed identity shift, particularly for people who speak Spanish and no longer live in rural areas, in their traditional lands. But as it pertains to what we're talking about on this podcast, I do wonder like how they're being seen by mission presidents who would have come from Northern Mexico, which is pretty different culturally, like even within Mexico, from Mexico State or Mexico City.

And, but they would have spoken Spanish because they're from, what we could call the colonies, in states like Chihuahua and Sonora, but like such a different vibe. And they're looking at these people and they're like, okay, you're one thing. And then the people who are joining the Church are like, no, we're not that, we're this other thing, but also we're trying to become something [00:54:00] else.

Like all of these layers of identity, I just find it so fascinating. Especially because, I mean, I don't know how many active Church members there are in Mexico because those statistics are not available, but the most recent ones were 1. 2 million members were active or inactive. And I'm not sure about the most recent Mexican census data, but that's just so many people.

So obviously a lot of people are having these identity shifts and ideas and maybe not conversations like verbalized, but there's reasons why people are doing what they're doing. And some of it aligns with broader trends in Mexican history. But some of it is very particular to people who decide to join the Church.

And then their families who are Church members of this US-based denomination, or this US-based religious body. And then, [00:55:00] but it's always been their church too. So I just think it's so interesting and there are other people who have written a little bit about this, but I think there is so much more that can be discussed.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. And I think you said this piece came through the International Art Competition.

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: We talked on our first episode, we talked with Laura Howe about the history of this competition and the way that it's embraced different types of materials. Like Heather was talking about earlier different. Like you said, the beading and the textiles here and, yeah, I just think that that's another great example of how the International Art Competition is encouraging members around the world to combine their art and faith and bringing it to a more global audience of Latter-day Saints.

Okay. Finally, at the end of each episode, I want to ask each of our guests to quickly share a Latter-day [00:56:00] Saint artwork that is meaningful or just intriguing to them. This doesn't have to be your very favorite, but just something that you think is interesting to look at or talk about. Heather, why don't we start with you?

Heather Belnap: Totally unfair! I just curated a show

James Swensen: to hear what you're going to say, Heather,

Heather Belnap: where there's so many artworks,

James Swensen: then you could, you get the, she's still, you might steal one of ours. So you get to go

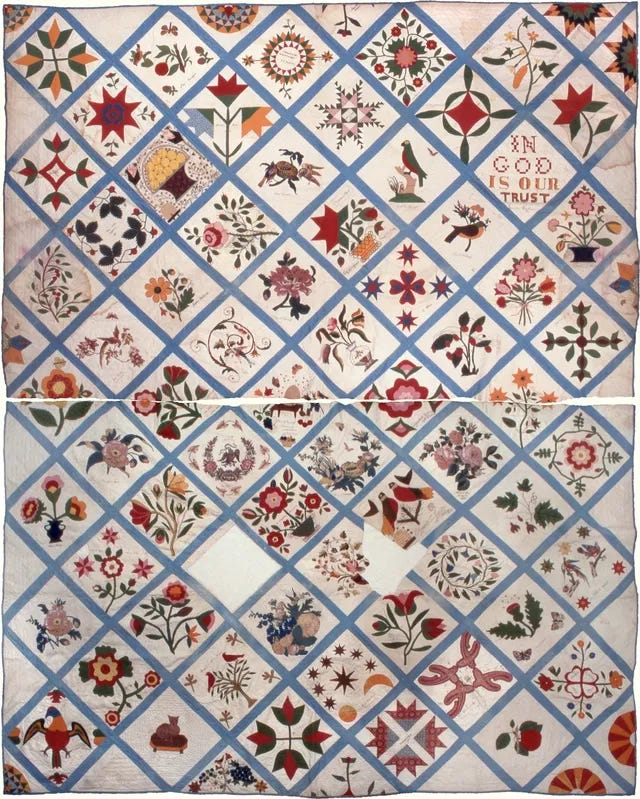

Heather Belnap: there's so many artworks that are there. Okay, well, I'll put in a plug for a work that is totally unfair. In the exhibition. It's the Salt Lake City 14th Ward's Relief Society album quilt that was completed in 1857. uh, the story of getting it to the museum and in the exhibition is a podcast in and of itself. It is of blocks, individual blocks that women, who were part of that Relief Society made, and that tell their own stories of, as individuals or families, and then when stitched together, it becomes a record, historical record of [00:57:00] the 14th Ward Relief Society. Then it was won at a bazaar by a young boy, and as he got older and had children, he didn't know who to give the quilt to, so he cut it in half, and then, and then that, the quilt ended up, you know, being scattered and going into these different kinds of directions. And, this work to me is such an important record, both of kind of individual and family history, but also of Church history and of just many, many wonderful lessons that can be from that.

So that's. That's my favorite. That's in the exhibition. How's that?

Jenny Champoux: Wonderful. I love that piece too. And it's so great that you were able to bring those two halves together. Rebecca, let's go to you.

Rebecca Janzen: That story was just incredible of the quilt, like I’m from a Mennonite background and so quilting is a big thing. It [00:58:00] is not something I can do, but, so for me, it was especially interesting because of that. I wanted to talk about one of the artists that you included in Work & Wonder, Ricardo Rendon.

Heather Belnap: Mm.

Rebecca Janzen: I wanted to write about him and Georgina Bringas in this chapter, but there was too much.

So hopefully in a future project, but all of his work, is like installation art. And this piece, it's like string and I don't know how to describe it. You can look on Instagram, at Ricardo Rendon 2014. But to me, it's really emblematic of a lot of his art that it's three dimensional in a unique way.

And it is similar to a lot of contemporary art trends that happen in galleries in Mexico City, but there's also always an element of some theological ideas, like, and particularly the idea of time, seems to [00:59:00] appear in a lot of his work and I'm, yeah, I'm sorry that I have not been able to see it in real life, but it's just really thought provoking to me.

Heather Belnap: We, and we had that recreated for the show. So he actually came and, like did it

Rebecca Janzen: So cool.

Heather Belnap: himself and installed his wife, Georgina's, piece. Really, yeah, really exciting to see.

Jenny Champoux: Okay. And James,

James Swensen: So my choice is going to be someone we've talked about already, and there's also in Work & Wonder, and that's Mabel Frazer's, The Furrow from 1929.

Yeah, it's, it's one of, it's always been one of my favorites. It's great as always to see it up on the wall. And so I'm really interested. I've been thinking about it for a while, and particularly interested in not just the work itself, but 4 years later, she writes a short little blurb for the Improvement Era about what it is and what it means and how she, you know, doesn't follow a school and yet it does. And so I just [01:00:00] love if it's so well within my research in terms of looking at the Great Depression and regionalism. And yet this distinctive artist again, Mabel is fantastic. And just with this distinctive artist working in Salt Lake, who's working, in Southern you, she's working, making some of my favorite landscapes at the time, but also just this of faith hard work and, working the land and all these things that just really resonate in that period that I really enjoy researching so much.

Jenny Champoux: Heather, do you need to say anything about that piece too?

Heather Belnap: No, I, I love, I love that piece so much and just to build, off what James was saying, Mabel was known for, being a straight shooter and playing talker, and in her, the eulogy that was [01:01:00] given of Mabel, it was said that, that she really only cared about two things and that was her religion and art and that those were, core to her identity and to the work that she did. And I think that that's just, you know, a really important point to take away from. A lot of the, the art and the artists that we've considered, is, you know, how it is an expression of faith. It can be a means of worshiping. It can be a means of exploring, but that just how grounded so many of these artists were in, in their, uh, religion and inner spirituality and how that guided them regardless of the subject. You know?

James Swensen: I think people like Mabel understood that art needs to be part of Zion.

Heather Belnap: Yes,

James Swensen: And she just, you know, she was going to do what she needed to do.

Heather Belnap: Right.

James Swensen: it's really great because, yeah, there's a phrase a contemporary used for that: she had a tyrannical grace. That I just really love.

In [01:02:00] fact, I wrote an essay about her and that was the part of the title and that she just had this force, this kind of force of nature and was not going to let anyone get in the way of, of producing these works that, that summed up who she was as an artist, as a human being, but also as a Saint, right? So it's really great that way.

Jenny Champoux: Thank you. All right. Those were wonderful pieces to share and so different, all of them. So I appreciate that too. Heather, Rebecca, and James, thank you so much for being with us today.

James Swensen: Thank you.

Heather Belnap: My pleasure. My pleasure.

Rebecca Janzen: Yeah. Thank you.

Jenny Champoux: It's been a great conversation about geography and landscape and Latter-day Saint art. For our listeners, thanks for tuning in, and I hope you'll join us next time as we examine how portrayals of bodies are used to express belief in the art. Amanda Beardsley, Mary Campbell, and Menachem Wecker will talk with us about the legacy of polygamy in the visual culture, feminist artistic approaches, and the Art and Belief movement of the [01:03:00] 1960s.

You'll definitely want to listen in. We'll see you then.

Thank you for listening to Latter-day Saint Art, a Wayfare Magazine limited series podcast. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. I hope you'll order a copy of the book to read the full essays and see all the gorgeous full color images of the artwork.

You can learn more about the book and other projects at the Center's website at centerforlatterdaysaintarts.org. If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to listen to the other episodes in this series. You can subscribe to Wayfare Magazine at wayfaremagazine.org. Thanks to our sponsor, Faith Matters, an organization that promotes an expansive view of the restored gospel.

And if you'd like to learn more about Latter-day Saint art, check out my other podcast called [01:04:00] Behold: Conversations on Book of Mormon Art. You can also learn more at my website, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. With more than 10,000 artworks, it's the largest public digital database of Latter-day Saint art. You can search by scripture reference, topic, artist, country, year, and more. We recently added a new section for art based on Church history, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price.

The website is bookofmormonartcatalog.org. That's bookofmormonartcatalog.org. Check it out and see what exciting new art you can find to enrich your study!