Jenny Champoux: Welcome back to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux. In Latter-day Saint Art, I'll guide you through an examination of the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. Please note that a transcript of each episode and images of the artworks discussed are posted at WayfareMagazine.org.

In this episode, we're considering how the human body is either displayed or hidden in Latter-day Saint art. Our guests will chat with me about the messages or beliefs that might be encoded into the representation of bodies. The discussion will focus on 19th-century photographs of polygamous families, the Art and Belief movement of the 1960s, and feminist artistic approaches. Our guests today are Amanda Beardsley, Mary Campbell, and Menachem Wecker.

Amanda Beardsley is the Cayleff and Sakai Faculty Scholar at San Diego State University and received her PhD in Art History from Binghamton University. Her research and publications have ranged from sound studies and feminism in Mormon culture, to science and technology studies, gender, and faith. Her chapter in the book is titled, “Latter-day Saint Feminism and Art.”

Mary Campbell is an Associate Professor of American Art History at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. A lawyer as well as an art historian, she works on the intersections of race, gender, and the law in the arts of the United States. Her first book, Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image, received the support of the Stanford Humanities Center and the American Council of Learned Societies. Campbell received her JD from Yale Law School and her PhD from Stanford University. [00:02:00] She clerked for the Honorable Sharon Prost of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and is a member of the New York Bar Association. Today we're talking about her book chapter, “Success in Circuit: Brigham Young's Big Ten.”

And then Menachem Wecker is the U.S. News Editor at the wire Jewish News Syndicate. He holds a master’s in art history from George Washington University. He has published frequently on the intersection of faith and the arts in both general interest and scholarly publications. And his essay is called, “Draw All Men Unto Him: The Mormon Art and Belief Movement.”

There is so much to talk about from these three chapters, so let's get started!

Amanda, Mary, Menachem, thank you for joining us today to talk about your chapters in Latter-day Saint Art!

Amanda Beardsley: Hi. Thank you for having us.

Mary Campbell: It's great to be here.

Menachem Wecker: Thank you.

Jenny Champoux: Okay. Before we jump into the essays, I want to ask each of you about your art [00:03:00] historical work. Amanda, we're going to start with you since you were a co-editor of this book project. Congratulations. I've loved reading the book. What an accomplishment. Really a landmark contribution to the field. Can you tell us about your vision for the project as a co-editor and what it was like collaborating with all of these authors?

Amanda Beardsley: Yeah, I mean, from the beginning the project was collaborative and so the vision actually was, it, I, I have to give a lot of credit to Glen Nelson, Richard Bushman, and Laura Allred Hurtado, who brought us all together initially. And so at first I was just an author alongside everyone else, and then, COVID happened and some changes took place.

And so, Mason and I were asked to be co-editors on the volume, which was [00:04:00] a huge honor to be given this project and to take the reins and figure out how to still make it ours, while also honoring that history that Laura, Glen, and Richard had kind of given us.

And so, collaborating with 22 authors, um, was, uh, an experience. I think it was such an experience because, and it was a good experience. I mean, I remember we did a, like a mini symposium, mini conference with the authors where we brought them together in Utah and were able to share our chapters, like just really early versions of our drafts with the chapters.

And I think those kind of moments were really generative for us. I know that like in my chapter for instance, like Menachem, like had given me some great advice and knowledge about like some of the Hebrew that was used by one of the [00:05:00] artists that I was featuring. And so it was that knowledge sharing that was for me, super exciting. And then, I think also just like the multidisciplinary-ness of it, that was also really exciting knowing that like, I'm working with, you know, a few art historians, you know, and the book is mainly an art history, you know, like book. But also bringing those disciplines to bear, I think on art and especially Mormon art history was another kind of exciting thing.

So, I think out of it all, it was just a great experience and one that required a lot of communication and a lot of patience on our author's parts, with Mason and I tackling such a large project. So we are, we're just really, really grateful for all of their work.

Menachem Wecker: And I think for some of us who just had to show up and not do that immense amount of work behind the scenes, at least for me, it felt kind of like [00:06:00] pilgrimage. Like it was really nice to come together as, as a community. I had forgotten about the Hebrew that you mentioned, but I know for my chapter, I got in touch with a lot of people who were, you know, who contributed other chapters and ran questions by them, and we looked at things and it was just, it felt great to have a community, which didn't happen on its own. There's a lot of effort that behind the scenes went into it.

Mary Campbell: Absolutely. And I have to say, because I continue to work in the sort of visual culture of the Church, but I'm also working on a book in a completely different area. And that's such solitary work that to come back to my sort of art historical roots and then have all of these people involved in it.

And again, like Amanda and Mason, I'm not quite sure how you held onto your sanity throughout the process. But again, that kind of communal scholarship that I had stepped away from was really wonderful.

Amanda Beardsley: [00:07:00] Mm-hmm.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. And Mary, just speaking about your work in this book, so you are, you have training as a lawyer and as an art historian. So, when I was in graduate school for art history, my husband was in law school, so I have a little glimpse into, you know, both worlds and I just am so impressed that you've done both.

Mary Campbell: Thank you.

Jenny Champoux: Could you, could you tell us a little bit about how that dual training is used in your work? How you draw on both of them?

Mary Campbell: Yeah, absolutely. So actually, my book, which looks at LDS visual culture and especially this photographer named Charles Ellis Johnson, who was working for the Church right around the turn of the century. It started out as a law school paper. And then that turns into an article that I published in the Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. And so, when I went back to grad school, I still had this kind of foot [00:08:00] in LDS legal studies, and then what became really interesting to me was the way in which the Church relied so heavily on images. To really mainstream itself and its members back into the nation after the scandal of polygamy and the ways in which sort of, the Church's appeals to more kind of standard political or legal interventions, whether it was taking cases up to the Supreme Court under the First Amendment or starting newspapers, the way in which that ultimately wasn't as effective as this move to really present a different image of the Church through, you know, I focused on photography.

So, through photographs and family photographs and then even the fact that, you know, like [00:09:00] Congress and the court in Reynolds v. United States in 1897, no, 1879, was talking all about this kind of terrible LDS image. And then you get Canon v. United States, and the court says, you know, it doesn't matter if you're actually living with multiple women, it's, you know, you look like a polygamist. So, it's like even the courts understood that LDS polygamy was a problem of image as well as actual kind of legalistic definitions of polygamy and cohabitation. That was a very long answer.

Jenny Champoux: No, that was fascinating. I hadn't thought about all those connections. Thank you.

Menachem Wecker: It just reminds me one of my favorite things about, what I've read about trying to authenticate Rembrandt paintings, which are so often copied, right, is I love how we know so much about them because he mismanaged his money so poorly and the state, in a legal context, had to come in and [00:10:00] take inventory of everything so that it could be put up to auction to cover his debts.

And of course, they said painting of and described it. And we have that kind of provenance, you know, we have that information because of the state, because of law. So, there's all these wonderful intersections of law and art that maybe people think, you know, don't necessarily think.

Mary Campbell: I mean, I think that's such a wonderful point. I'm teaching an art law class right now, and I think the students are really kind of shocked, but pleased by these intersections, right?

Menachem Wecker: Somebody, I can, sorry. If we turn this into a 17th century Dutch

Mary Campbell: Sorry, old master,

Jenny Champoux: That's, that's actually my expertise, so I love it.

Menachem Wecker: I think Rembrandt was sued by someone also, and we have like the whole court case that the likeness wasn't good enough. Right? So we had to like maybe prove in court that the painting was good enough. So anyway, that's

Mary Campbell: right? Any, sorry, just to finish up, like Dürer like starts the, you know, 16th century German Master Albrecht Dürer starts out copyright because somebody, an [00:11:00] Italian, copies one of his prints and starts selling it. And so, a lot of people, again, know Dürer because he got so feisty from a legal standpoint.

Menachem Wecker: Yeah.

Mary Campbell: So

Jenny Champoux: Yeah.

Mary Campbell: rich intersection of the two disciplines.

Jenny Champoux: Okay, Mary, sounds like you need to start your own Art and Law podcast.

Amanda Beardsley: Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: How fun.

Amanda Beardsley: Yeah.

Mary Campbell: you.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. No, I, I'm really enjoying that. Yeah. So much to think about. And then, Menachem, you're a journalist. I know today you're not speaking in your official capacity as a journalist there, but as someone who's done some art, you, you've done art history training and you've written extensively on art and religion. And I really loved reading some of your work on thinking about how art can bridge divides by expressing the ineffable. So, I want to ask you, what do you see as the value in studying the art of religions other than one's own?

Menachem Wecker: Mm-hmm. Yeah. So, my, my thinking changed on this at [00:12:00] some point, and I don't remember exactly when I, I started really writing about this intersection maybe 25 years ago, and I, I've done it almost exclusively as a journalist. If one squints one's eyes and uses a lot of imagination, occasionally I impersonated a scholar.

And I, I think in the beginning it was really that, like, I thought it was fascinating that there was this group of people, and this will be relevant to Art and Belief I think later on. There was this group of people making work for an audience that didn't exist. And I found that fascinating because I think that religious communities very often want art to be enlisted in the service of talking about how beautiful that tradition is.

And, you know, and, and the art is lovely if it doesn't get in the way of the message. Some people would call it a distinction between illustration and art. That will, that comparison will offend some people. It will excite some others. But, but the kind of storytelling, you know, [00:13:00] the kind of art as a way of let's say kind of doing PR for the, you know, for the faith tradition or highlighting that which is positive.

Some would say kitsch. I mean, you know, whatever terms one uses are going to be complicated. Artists who are, you know, someone who's trying to do something different from that often doesn't find much purchase in the, you know, in the religious community. On the other hand, the art world, you know, for centuries now has not been centered around faith communities in the way it used to be.

So, work ends up being kind of too focused on faith for the art world and too, you know, focused on art, let's say for, for the faith community. So, there were all these people trying to make serious work and, and finding no audience. And I thought that was fascinating and the way that, like, I've always been interested that there are biographies, there's podcasts now that all center on, somebody starts a company in their parents' garage or something, and then it becomes a billion-dollar company. And therefore, we draw a straight line and say this person was a genius in every decision that she or [00:14:00] he made. I'm much more interested in, you know, the band that starts and gets no success, but keeps playing for, you know, for many years.

So, making this work without an audience is very interesting to me. And so, talking to people, it became very interesting to hear why they were doing it, why it was so important. Gradually, I think I came to see that art is a really good kind of language to discuss faith. Faith is very hard to discuss even within a group.

We say God, and we mean, you know, at least as many things as the number of people in the conversation. Words can be very divisive, particularly between faith traditions. It's really hard, you know, to find some kind of translating mechanism. But art, you can talk about a red and a blue and a square and a line.

We can say, why did you put that thing in this painting? Why did you sculpt in this way? And it becomes a way to enter a conversation that maybe doesn't start with faith but can move there. And once there's familiarity. It struck me that every work that somebody makes that comes from a faith tradition, no matter what the subject has some kind of aspect of [00:15:00] self-portraiture in it.

Like one's faith and beliefs inform it, even if it's not a portrait. The stakes are huge at times, depending upon the faith tradition. It could be heaven and hell, it could be life and death. Like these works are aiming quite high. That doesn't mean many or all or most of them reach the kind of ambition that they aim for.

But I think it's this fascinating group of works that that often, doesn't get enough attention and can be really complicated. And I think it can be, like, art can definitely be a bridge that helps us understand one another. But I think it's also worth noting that it can do the opposite. Like, you know, you go through museums and, you know, contemporary sure, I'm, I know more about the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, but you see lots and lots of works that were literally weapons that were used to demonize others and to be used to drum up hate. So, I think it's, it's a tool that's powerful and, and can be used, you know, for good and it's worth celebrating that. But I, I wouldn't want to make it sound like it's only used for good. It can be quite dangerous also [00:16:00] if it's wielded inappropriately.

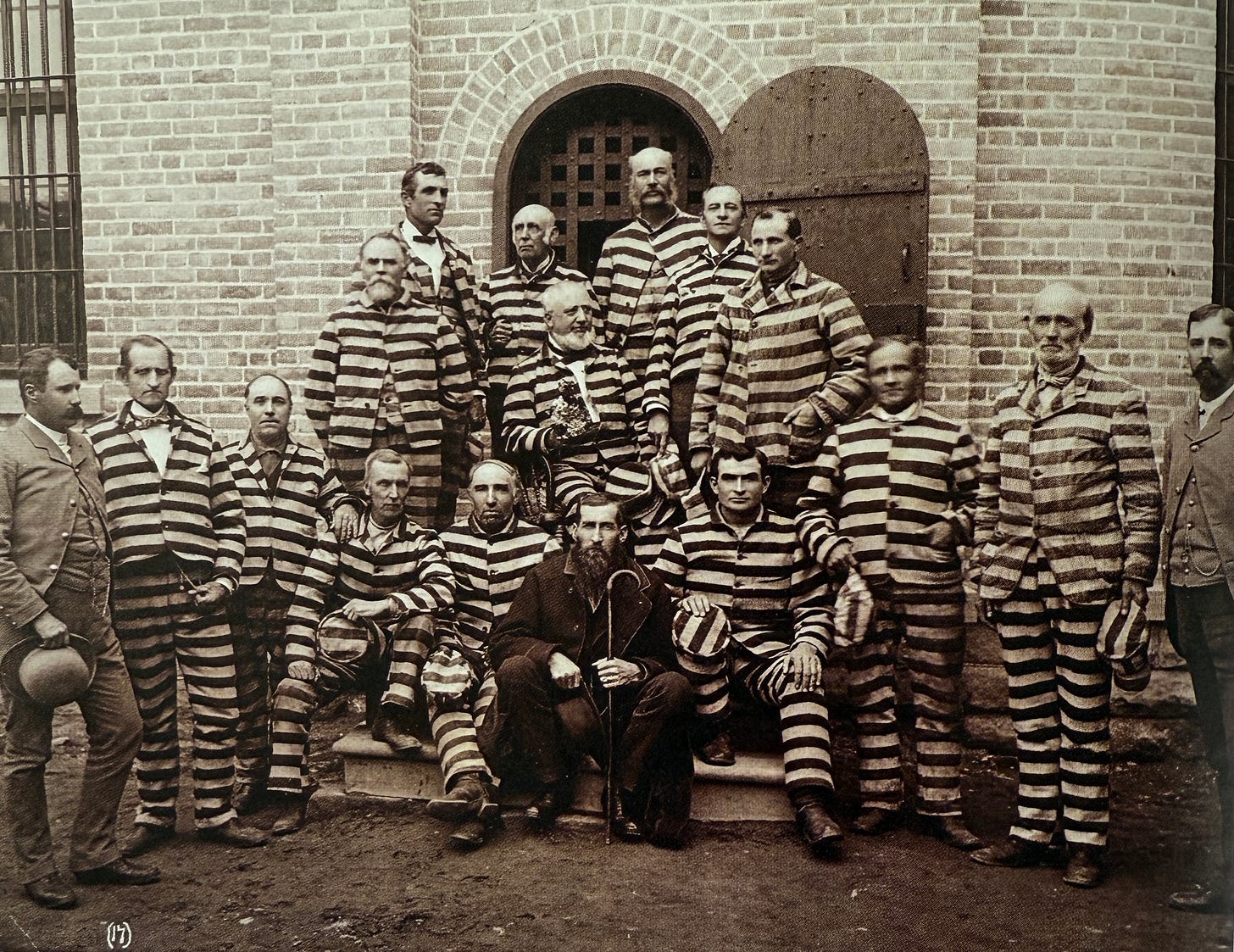

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, that's great nuance to that discussion. Thank you. All right, so let's dig into your essays. Mary, I want to start with yours. You focused on an 1865 photograph. It shows 10 of Brigham Young's daughters, and you point out that it's interesting, you see these 10 young ladies and they're all dressed in a similar way.

Their hair looks the same, they're about the same age, and so you argue that it's possible to read them even as one body. But then at the same time you have this really complex family tree represented by, you know, they’re siblings and half siblings and adopted siblings and cousins, and some of them end up being sister wives in the future. So, it's, it's this really interesting dynamic. Can you tell us more about that and what messages are encoded onto their bodies in this image?

Mary Campbell: Yeah, absolutely. And one thing that I thought was just [00:17:00] so fascinating about the work is the way or the ways in which it would play very differently depending upon the audience. So, for Young and his wives and even the young women, it's a portrait. It's, it's a sort of family portrait, right? It's a kind of testament or memorial to all of these relationships and so often relationships that really couldn't safely be spoken outside of a very small community. I think I started thinking about that because as I was going through archives of LDS photographs from the time, um, you would see these pictures that were actually sold as a type of curiosity, a kind of almost, I mean, kind of freak show image, a sort of vignette with Brigham Young in the [00:18:00] center and these multiple wives.

And so, tourists who came to Salt Lake City during, you know, the late 19th century and even into the early 20th century, they, these were souvenirs. They were, they came, these tourists came. These non-Mormon tourists came expecting to see a very particular view of a sort of like freakish domestic relationship. And they bought the souvenirs as a result to like take them home. And yet I found the same images in the archives of various LDS families, right? So, the pictures were effectively working as a sort of tourist attraction for one audience and then family photo photos for another.

And that really got me thinking about the idea of audience in the context of, you know, kind of turn of the century LDS [00:19:00] art. And to think about the ways that it would function differently to think about the sort of importance again of the female body in representing a sort of relationship that couldn't be shown, the stakes of their beauty, sort of being costumed in this way that would've struck an audience regardless, as really refined. But then the way in which, if you were a part of this community and you knew Young and you knew his family, that you would read it in a much different way.

Jenny Champoux: This reminds me a little bit of a conversation we had in episode two where we talked with Ashlee Whitaker Evans about her chapter, and she mentioned these little paintings by Frank Treseder of the Utah Penitentiary that were, um, Treseder gave them or sold them to men who had served time in the penitentiary for [00:20:00] unlawful cohabitation.

Mary Campbell: Yeah,

Jenny Champoux: And it's kind of a similar thing where if you know the backstory, then you know what's happened here. But to an outsider, it might just look like a nice kind of landscape portrait of Utah scene with some buildings. But you have to, you have to know the context. There's something encoded in it, that reads differently for insiders and outsiders, kind of like these polygamous photographs.

Mary Campbell: and I actually had a friend as I was working on this, totally randomly be like, oh yeah, I'm related to that man. Do you know what I mean? So, there's always this shifting between sort of coding, hiding, you know? And at this point, photographs of polygamist, family photographs could be entered as evidence. In court proceedings, right?

So, it's sort of the, you know, daring and perhaps not so smart man [00:21:00] and family that's gonna be like, here we are in our glory. So, the ways in which you have to hide if you are living under that sort of, you know, social scandal, but also real threats of legal action.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Okay. So, Amanda, I want to shift a little bit from these 19th century images to some of the more recent 20th or 21st century feminist approaches you see in the art. And one that you mentioned, but didn't actually get an image in the book. I just have to bring it up because it's my cousin Becky Knudsen who did it.

So, it's a hand-hooked rug that Becky made of, um, it's, it's my great-great-grandmother, her great-grandmother, Lucy Heppler, Louisiana Heppler, who I just, I love. So, I have a personal connection to this in my own, [00:22:00] family history and, we'll put an image of it in the, in the show notes.

But how do works like this, that draw on the lived experience of women, in this Latter-day Saint tradition, how do they help fill in narrative gaps, right? Or show what life was like for these women or contribute to the larger story?

Amanda Beardsley: Thank you. And also, I love that you have all of these different connections, Jenny, that you kind of bring in. It shows kind of like the vast amazingness of your network, uh, everything it seems like. And so, I love it. Yeah. So this work, I came across it, when Linda Jones Gibbs, who's one of the authors in our book, shared with me her exhibition catalog for the Out of the Land exhibit that she curated in 1992 and 93 [00:23:00] in Washington, DC. And the work itself features a woman in the middle of the quilt, and she has her arms kind of crossed with different types of fruit it looks like from a tree in her hands. Uh, that must be your, your great, great

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, that's,

Amanda Beardsley: Okay.

Jenny Champoux: right.

Amanda Beardsley: That's really cool and she is giving that fruit to, I don't know, maybe progeny. I don't know a lot about this work, and I would love to know more about it,

Jenny Champoux: Oh, I can tell you, I can tell you who the children are, if.

Amanda Beardsley: Oh, please do. Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: So, and I think this fits in nicely with, with Mary's discussion too, because, um, so Lucy's husband was sent on a mission to Germany. At the time, she had six children. When he came home, he brought a German widow with him and her six children and told Lucy, um, I feel like I should take this German widow as [00:24:00] a second wife. That was very, very difficult for Lucy. She really struggled with that. Finally, she agreed, but, in the meantime, the German widow, Katherina, she got sick with typhoid that she'd caught on the ship coming over and she died. And as she died, she pled with Lucy to take care of her six children. So, Lucy agreed. She adopted these six children and then she had 12. And then she had six more. So, she ended up with 18 children.

Amanda Beardsley: Okay.

Jenny Champoux: It’s just amazing and that, so, but there's a story that's been passed down through our family of how Lucy would sometimes feel that she would want to, I mean, they were just kind of eking out a living in this little Utah settlement in Glenwood, Utah. And she would want to give larger portions of food to her biological children. But then as she approached the table, she would force herself [00:25:00] to cross her arms so that the larger portions actually went to the adopted German children. That's become and passed down in our family as a kind of symbol of unity and sort of gathering and reaching out and including others and sharing our blessings with others. And I just, I mean, obviously for me she's like a great matriarch and personal example to me. And so, all right, Amanda, tell us more about

Menachem Wecker: If I can cut in for a second. Rhymes with a long art, historical tradition. We could go back to Rembrandt now if we wanted to, but not necessarily, of depictions of Jacob blessing Joseph's sons and the biblical story talks about how he put his right hand, which incidentally, the way you say left hand in biblical Hebrew is weaker right hand. So, everything is put in terms of right hand, but he puts his right hand on the younger child and, and the left hand on the [00:26:00] older, and Joseph says, you've got it wrong, switch them. But there's a long tradition of, of blessing children with crossed arms, you know, crossed arms and it's. To look at that kind of art with this.

Jenny Champoux: Oh, yeah. I think that's a great connection. Yeah.

Mary Campbell: if I can jump in, and just going back to what we were talking about, um, in terms of audience, the idea that, you know, your family would have this incredibly kind of personal iconography that continues to go down through the generations, I find so moving and then so fascinating from an art historical standpoint and goes back to the idea too of how works, right? And the

Jenny Champoux: yeah,

Mary Campbell: it's really good.

Jenny Champoux: Amanda, I want to go back to you and just have you like, with that understanding of what this piece is about, how does this fit into, right, these kind of feminist approaches that you're talking about, including women's experiences?

Amanda Beardsley: Yeah. It [00:27:00] sort of further reinforces what I argue in the chapter is that there are these kind of like counter archives that are created to like a dominant, kind of like genealogical archive because genealogy in the Mormon church is so to its functioning. It creates this narrative of humankind that's very, very important.

And I know that like in my family, collecting things and going to, you know, like the various genealogical centers and kind of bringing together that family tree, which I see in this work is featured right behind Lucy Heppler is I think very, very important. And so, I was very curious as I was observing a work all as many works as I could in exhibitions as I could. What are some of kind of like the salient themes that are emerging here that might also, you know, coincide and depart from feminist art as maybe we know it art narratives as we know it, but I think there's a few ways, especially [00:28:00] in this work that we see. I think what Mary was saying about the ways that histories are passed down, it sounds like it's so interesting that you're sharing kind of your story of how it's passed down.

Because I think it could be passed down through this quilt. Right. Which is generally something that is not considered, you know, like within art as like the high art with the capital A, right? It's something that is usually associated with women's labor. It's something that a, a quilt to something that warms you.

It's comforting, it's associated with like nurturing. So, I think there's some really interesting associations here,

That oral history that was passed down, I think through your lineage, you know, through your family is also, I think, I know a lot of feminist kind of scholars have written about that in particular because there haven't been very many outlets or of discourse that have allowed them to tell their stories. So, I was really [00:29:00] curious about that. And so, when I was working on it and trying to maybe create like a linear-ish history of those themes, this exhibition and this work, for me, reflects an attempt to kind of document maternal lineages and patriarchal religion, right, through these, um, measures that are like associated generally with women's work.

On the other hand, as my chapter argues, the upsurge in art considering like Heavenly Mother, which I think this was one that also kind of related to it, but I had, I was talking about different exhibitions. It represents a type of feminism that is both validating to kind of cisgender women, so it really validates that kind of experience, but is also really exclusive to them. And so, it represents kind of like a [00:30:00] wave, if we want to look at the history of feminism as waves.

It represents like a wave of feminism that is a little bit more, um, insular, I think, when we think about the history of feminism. So, in other words, it reflects the steep investment in, like, for me, a gender binary and like, that might make any expressions outside of those associations of like woman as it's attached to mother, a little less validating.

And so, I've seen, you know, within Mormonism, attempts to kind of rework this and we'll talk, I think a little bit later, hopefully, about Angela Ellsworth's work, right? Um, that, that both align with and kind of depart with how we understand written histories of feminism. But yeah, I think that's a very complex kind of like narrative of it.

But it's so exciting to hear that additional information from you because it does align with some of the arguments I'm making [00:31:00] in my chapter.

Jenny Champoux: Well, Amanda, thanks for humoring me and letting me bring a piece that is very personally meaningful to me. I was just thrilled to see that you mentioned it in your chapter, and I really appreciated that your chapter showed the value of thinking outside of traditional norms of materials and styles and even histories.

And like you said, thinking about oral histories and thinking about domestic crafts and quilts and hand-hooked rugs, and that the process of those kind of works is actually important to telling these women's stories. So yeah. Thank you so much.

Mary Campbell: Amanda, I'm just, you know, so happy in your work to find somebody who's really exploring that. And that seems, you know, especially so many LDS women are creating a sort of usable past for themselves to point out, you know, the kind of [00:32:00] necessary limitations within that and the way that sort of, you know, aligns with the kind of larger trajectory of feminism, which is so often, you know, obviously about straight, white, privileged women.

So just to say that I think your scholarship is amazing,

Amanda Beardsley: Thank you, Mary. You were the one who like, really, I mean this is like, we go way back because I was a master’s student when I met Mary for the first time at the College Arts Association and like fangirled over Mary's work and was like, Mary, like, can we stay in touch? And then we're in a book together and it just like so exciting full circle moment for me. So

Mary Campbell: because we were on a panel too in what, 2018?

Amanda Beardsley: Yeah,

Mary Campbell: we keep having these intersections,

Amanda Beardsley: yeah.

Mary Campbell: really great. And yeah, again, to be in the same book and to have you editing it is, you

Amanda Beardsley: Yeah.

Mary Campbell: to me too.

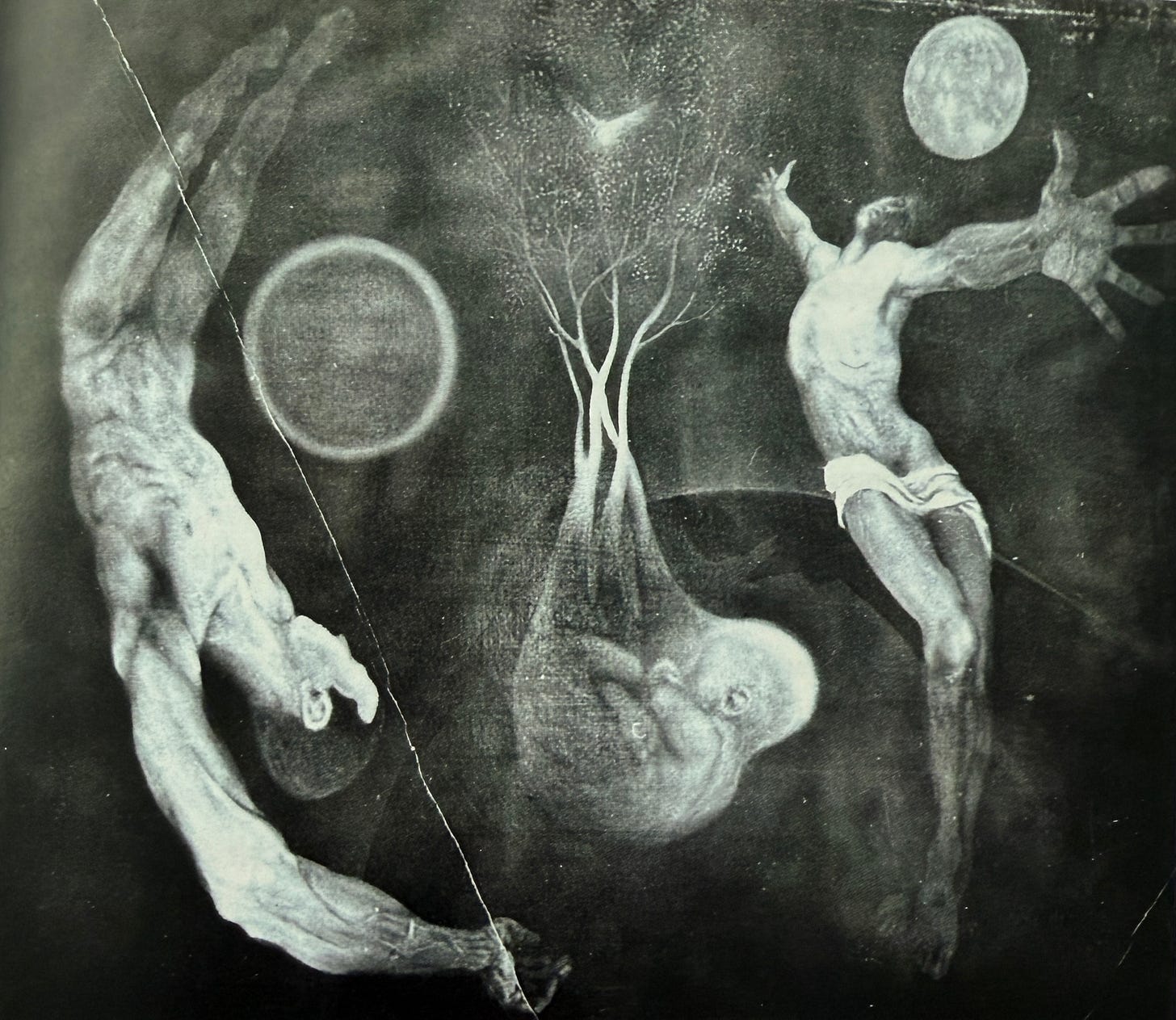

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. [00:33:00] Wonderful. So, Amanda's chapter looked a lot at art by women. Menachem, your chapter looked at the Art and Belief movement, which, tend, a lot of the artists focused heavily on the human figure and especially the male human body. You started off the chapter with this discussion of a piece by Gary Ernest Smith called Eternal Plan. It's from 1966 and it sort of, it seems like, kind of kicked off the movement or sort of symbolized what they were trying to accomplish as they began this movement. And I feel like it represents a tension in that the piece is both, represents very detailed human anatomy. There's a real focus on the human body, and at the same time, it's also very conceptual and a little bit surreal almost. Can you talk to us about that tension and how this was different from what other Latter-day Saint artists were doing at the time?

Menachem Wecker: Yeah, I'll try. I think the question [00:34:00] is much better than the answer that's about to come. So, I think people should, you know, understand also my information might be dated, but there is supposed to be a massive tome, I don't know, hundreds of pages coming out about the Art and Belief movement, by someone who knows

Jenny Champoux: Vern Swanson,

Menachem Wecker: So, he forgets more about Art and Belief in a, you know, in a day than I'll ever know. So that would be a good thing to look at it.

You know, Picasso said that it took him a lifetime to draw like children. My youngest is three years old and I feel like I'm trying to impersonate him in my writing. Sometimes I, he does this interesting thing where I teach him a new concept or something and you know, let's say the concept is justice. I'm not teaching him justice, but he'll immediately ask, “what is not justice?” And like trying to understand the positive by what it's not. And that was kind of the key to this chapter, like Art and Belief and this is kind of at the core of what Art and Belief is. The question of what it was not was almost as important to me.

It was so ambitious. I love. Um, you know, the story kind of for [00:35:00] me revolved around these four characters, two of whom were living. So, and are living. So, I was able to talk to them. I love Gary Ernest Smith's name because if you add an ‘A’ earnest is really what they're aiming for in a kind of way.

And whether one thinks that they succeeded or failed, or whether one looks at what, you know, when one looks at the impact. The earnestness, I think, is really a key in trying to define what they were after. I thought this work was so interesting for two reasons. Number one, you know, Gary told me this great story about how he got a call from BYU that this painting of his was on the floor in a closet with a bucket on top of it.

And, you know, and sometimes in, you know, in journalism, somebody tells you something and in the moment you're like, this is so good that the article's gonna revolve around it. This is such a good anecdote that it's gonna lead. And it wasn't just that it was in the closet, but the bucket being on top of it somehow was like the detail that propelled it and it kind of became, it was interesting kind of, I think I, [00:36:00] I don't remember what term I used, but almost kind of it seesaws back and forth because the university called him up and said, do you want this? And he said, sure, I'll take it if you don't want it. He repossesses it, then the school takes it back.

But then when I went looking for it, nobody had heard of it or seen it. So, it kind of felt to me like a metaphor for the movement at large that like, you know, the jury's out in a kind of way what the impact is. It's not clear who wants it. It's this kind of biblical, you know, prophetic voice kind of crying out in the wilderness and nobody hears the sound.

So that was one thing, the kind of physicality of this object and the journey it went through at BYU kind of stood in for the movement for me. It was also interesting to me that this is a work that because it had, I would call it a semi-nude form. I mean, it is a, it is a form that would strike a lot of people who spend a lot of time in museums, studying art history textbooks, as not nude. I mean, a partial nude, and yet it was too much. So, for one of the presidents of [00:37:00] BYU, who, you know, who apparently said it had to be taken down later on in the movement. Trevor Southey makes a lot of paintings that for a lot of people would be much more kind of problematic.

But the idea of like, of, I've always been interested, and again, I don't remember if this was in the chapter, but a lot of this rhymed with things that I knew about Orthodox Judaism. And, and there is that like people who study to become medical doctors and people who are doctors, even if they are devout, are exposed to the human form, you know?

Right. I mean it is, but there's a kind of exemption sometimes if one is saving lives, if one is diagnosing, if one is studying the body that is not seen as something that is going to be a temptation or, you know, or problematic, it is seen as professional and, and why is it? Really that an artist who's studying from the human form is not thinking as professionally as somebody who's training to be a medical doctor.

But I've always thought it's interesting that in a [00:38:00] lot of faith traditions, the act of making art is seen as less important, I would say, in terms of, of the value of it.

So, it's easier to say, well, just don't work from the form. Can't you just draw a still life instead? Can't you, you know, can't you do something, you know, make a, make a pretty flower instead that, you know, you could learn from that, and one can learn from, from flowers. But of course, there's a complexity to the human body.

It's not a, it is not an accident that that's something that one has drawn, you know, has studied throughout the age. So, the idea of like what this form was, was it too provocative? And I got the sense returning to that earnestness that like I got the sense that Gary was even surprised. Like I think he was so moved by the vision and what he was trying to get at and thought that he was trying to do something that was more complicated, that was more nuanced, that was deeper, that was devout and firmly rooted in, in the art world.

And I think he was genuinely surprised and maybe to some extent like that surprise endured that this movement [00:39:00] wasn't taken more seriously in the Church. That here were people who were trying their best to do, like, you know, to do two things at once, right? To be a, a foot in the Church and a foot in, in a serious art world.

I was able to spend quite a bit of time with Gary and with Dennis Smith. It got a little confusing with the two Smiths both, I think, born in the same year. Unfortunately, I wasn't able to talk to Trevor Southey or Dale Fletcher, who Dale was a few years older, uh, was, was quite a bit older. Trevor Southey, I think a couple of years older. But there was also this wonderful documentary that had just come out that I was able to review and, and to talk to the, to people who put it together. And there was a great recording of an interview where Trevor was talking about the kind of, I think it was Trevor talking about the disappointment of having had a commission and, and hearing back from the Church that there were an insufficient number of buttons and in a clothing, it wouldn't have been accurate to that time.

And saying, well, who cares about the number of buttons? And I think that's an interesting, you know, patrons and artists have argued, you know, for a long time, Michelangelo is [00:40:00] maybe one of the, the most notorious examples of this sort of thing. But what role does art play? Like, do the number of buttons have to be accurate to the time?

Is that more important than the composition, than maybe the feeling? I think some of those questions kind of run in parallel to what does it mean? To use the human form, what is the point where the human form is playing a role that is, you know, that is artistic and not, you know, a temptation that is gonna lead people astray, where does one draw that line?

Mary Campbell: If I can just add to that. I'm writing about this right now for another presentation, but to think about the way, sort of going to that idea of whether this is like visual temptation or whether this is, you know, a, a different love affair with a kind of idealized. Male body new to think. I think it's something that we, you know, as art historians tend to suppress a little bit, if you look at, because apparently, we're just gonna be talking about Old Master [00:41:00] painting. But if you look at the trajectory of you know, western art between say the Renaissance and the middle of the 19th century, there's this incredibly sort of regimented curriculum in which students, almost always male students, learned how to make kind of the highest forms of art and the real kind of pinnacle of that education process was the right to draw from the body and usually the nude body. And these sort of drawings of the nude body were referred to as academies. Um, and these formed the basis for, again, the sort of highest genre of art, which was referred to as the history painting. And that it can be the same kind of, these, these interests can intersect in one work and one artist's practice, and they don't need to negate [00:42:00] each other.

Menachem Wecker: and there's, particularly with Art and Belief, there's this wonderful thing that happens, which is when Trevor first, Southey first moves to Utah. He ends up passing through in New York and he goes to the 1964 World's Fair and sees Michelangelo's Pieta there. And, and he, that clearly makes a big impression on him, and he is very unimpressed with, with the art from the, with, with art from the LDS church that he sees there.

He's very impressed with the Vatican Pavilion. And he later writes, including two Church leaders when he is trying to get a commission. And he says the Church needs to have better art. Like the, you know, the Vatican like this. Michelangelo was wonderful. We need our Michelangelo. And the fascinating thing to me is this is such a tragic story of like, you know, various leaders of the Church had, you know, gave speeches where they said, where is our Michelangelo, where is our somebody else?

And, and now they, they added an element which, which was, they said that someone who's, [00:43:00] you know, a Michelangelo with the right beliefs would've made even better work. A Michelangelo working from, let's say truer scripture or more compelling scripture, whatever the right term would be used, think about how much he could soar to a higher height, you know?

But this idea of wanting that great quality, wanting to represent the Church in a great way, where the art was as transcendent and, you know, and great, and magical as the belief was, was at least what Church leaders were saying they wanted, it was what the Art and Belief movement said they wanted.

I'm not, I'm not an expert here, but the closest thing I've seen of somebody working within the Church tradition trying to be like Michelangelo is in my mind, Trevor, you know, Trevor Southey. But for a whole host of reasons and reasons that rhyme with other examples of artist and patron throughout history and other traditions, it didn't work out. And as I was talking to the two Smiths and as I was researching this, it just was so sad that, you [00:44:00] know, that, that this didn't work out.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, so you explained in the chapter it sort of ended up being too edgy for the Church, but too religious for the secular art world. So, it wasn't really accepted

Menachem Wecker: right.

Jenny Champoux: in, in either, at least not at the time. I feel like there's a little bit of a moment now where we're kind of scholars are kind of looking back to it and trying to,

Menachem Wecker: Right.

Jenny Champoux: bring that history back to light. And I know there are certainly some artists that are still working in

Menachem Wecker: Right.

Jenny Champoux: of trying to develop a distinctive Mormon art and iconography.

Amanda Beardsley: Well, it makes me think Jenny too, and Menachem and Mary, like, it, it makes me think about the alignments between the construction of like gender or even like masculinity, both within images, through particular bodies, especially with the parallels that you point out in your chapter between Southey and his sexuality, right? And that outside of the artistic renderings that are happening with these kind of larger calls [00:45:00] for the Church to have a great art that reflects maybe a kind of like very masculine or like culturally, um, like legible, kind of like, I don't know, image. Really fascinating. I found that fascinating chapter too.

Menachem Wecker: But just like, you know, I, I got the idea also that like, you know, unlike maybe many other artists, like he was, like, he, he was making works where he was putting his self, you know, his own portrait in the piece in a way that made it feel like in real time he was trying to use his art to understand his place in the world and understanding his place in the world by his, you know, it was a, like, he was living and, and, and painting himself, I think seemingly co-terminus at times, to me, in a way that's unusual, like a lot of people.

And, and you know, there's, I think there's an image that, a self-portrait of Gary Ernest Smith that I think is in my chapter also, where he's also doing that. But the idea of like, you know, using one's art, [00:46:00] not only looking in a mirror and trying to transcribe what one sees, but trying to, to figure out one's place in the world and one's place in the painting at the same time is very interesting to me. Because those, you know, art imitates life, and life imitates art as I think Oscar Wild said.

Jenny Champoux: This was such a fascinating discussion. I also, I just, I was kind of struck by your description of the story of how this piece was bought by students at BYU and then was on the wall at one point, and then BYU President Wilkinson said, apparently said, take it down. It was later found under this bucket in the janitor's closet. And it just echoes so clearly the story in Glen Nelson's chapter about Dibble who had, and we talked about this on episode three, of a very similar experience where he has this kind of abstract modernist art piece. It's a little different maybe from what was in Latter-day Saint art culture at the [00:47:00] time. And take at a museum up in Logan and then ends up, right, tacked to the wall in the janitor's closet.

It was just kind of striking to me that it's almost the same story that happened to these two kind of mid-century artists who were trying to push the boundaries a little bit, but I think in a faithful way, trying to reconcile art and belief. But finding some pushback from the institutions

Menachem Wecker: I don't want to be callous to anybody's

Jenny Champoux: Mm-hmm.

Menachem Wecker: of course, but like if one is an artist who's trying to work out of a faith tradition, creating work that is ignored and misunderstood seems to me to be much more aligned with some of the central religious texts in which, you know, those who, those who understand the truth, those who are part of the right path are usually few and far between and persecuted.

Nobody should be [00:48:00] persecuted, of course. But there's a kind of interesting parallel sometimes between artists working in faith traditions and the religious material that they are mining if the work doesn't gain widespread purchase and goes through some of its own kind of trials and tribulations in the wilderness, as it were.

So that's, that's also something that I think is kind of common in the broader areas.

Jenny Champoux: Okay. So, I want to keep thinking about the male image in art. And Mary, let's go back to your chapter, because even though you focus mostly on this image of Brigham Young, 10 of his daughters, you pointed out that this was actually kind of unusual. That the wives and the daughters usually don't appear in these photographs.

But we do have, at least not as often as we see, maybe men with other polygamous men maybe in jail together, or men with all of their children from their different wives. So, talk to us about that and how [00:49:00] these kind of images were generally obscuring the presence and contributions of women.

Mary Campbell: Yeah, absolutely. And you know, you do get pictures of women with like their female children occasionally. There's one with Zina. There are like three sort of generations of Zina. But so often you'll either see LDS men with one wife sort of these of generations of LDS men.

And there's one of Wilford Woodruff with, you know, his first son and then his first son's son. And they're sitting in this carte de visite and everybody, it is presented is self-presenting. The way, you know, late 19th century, early 20th century upscale, kind of upper middle class [00:50:00] people would present themselves at a photographer's studio. And it is interesting to me, and Brigham Young is doing this, you know, early on he loves photography. He seems to be getting himself photographed all the time, but he only sits for portraits with two of his wives. And then there's a third one where the face has been scratched out. So again, so often I think there's this kind of absence in the archive. Of, you know, both polygamous families and their fullness, which again, would've been a really bad idea from a legal perspective, but also of, you know, what is identifiable as a polygamous wife, which then really I think memorialize, at least visually so many LDS women's, you know, real commitment to polygamy [00:51:00] their, you know, the sort of suffering they underwent, often emotional as of the practice. What happened to so many plural wives after, you know, the First Manifesto, the way in which so often husbands would essentially discard, the sort of latter plural wives and, you know, I have a relative that happened to. So there again is this kind of visual absence, and I'm thinking even of, you know, my own polygamist ancestor, William Flake, and I don't think you ever, at least the family photos we have, you don't see him with his two plural wives.

Instead, we just see him on a horse, right? And the family story is always that, you know, the first wife, Lucy Hannah, who's my ancestor, and then the second wife, Prudence, just got along wonderfully and it was very happy. And then I was doing more research, and it was like, [00:52:00] oh no, Lucy Hannah was in like black depression after Prudence came along and sometimes couldn't even get out of bed. So, the sort of importance of the ways in which these plural wives are memorialized both visually and then, you know, as Amanda discusses in these other traditions, even including oral traditions, there is a sort of absence that I think now so many scholars are trying to fill in.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, that's so, so great. Thanks for sharing that. And Amanda, I feel like this ties in so well with your chapter too, because you mentioned that Angela Ellsworth earlier, her seer bonnet pieces. And I love the way you described these in the chapter and it's interesting to me that even in these feminist pieces, the female body is, not always, but is often missing, or invisible still. Talk to us about that. Why do you think that is? I would [00:53:00] love to have you talk more about these seer bonnet pieces.

Amanda Beardsley: Yeah, the Seer Bonnets are like a favorite of mine and of a lot of people's because they're part of her, what she calls the Plural Wife Project. So, we're also working with the 19th century kind of polygamy. Uh, she focuses on sister wives as what she calls like this point of departure for discussing contemporary issues around non-heteronormative relationships by reimagining a community of women with their own visionary and revelatory powers.

So, the project really consists of like performances and sculptures, including the seer bonnet series. So, it's part of a larger kind of like, thing, that she's been doing for years. This series of bonnets, though, in particular, they're made from pearl-tipped corsage pins and fabrics set at different heights on steel and wood pedestals. [00:54:00] Each prairie style bonnet is meant to kind of represent each wife of the 19th century LDS leader, Lorenzo Snow, who faced federal charges for polygamy. And so, when you look at these, and I saw these on exhibit at the Utah Museum Fine Arts years ago, but you see that like, the thing I was struck with was how gorgeous they are and how painstakingly they were made because there are thousands of, corsage pins, right, that are put into this fabric. The exterior of each bonnet has this kind of like exquisite patterning with these pins. And it's like this beautiful mosaic of swirling shapes and textures and the pearly white designs and kind of alternating heights give it like individual kind of, I don't know, individuality.

That's very subtle with them, in contrast to kind of like on the inside, when you look [00:55:00] in, you see there's this kind of violent underbelly where the corsage pins are revealed. On their pin side. Right. And you have to imagine that putting these bonnets on would, I mean, it would kill you probably, right? Like, you try and force that on your head and it's just like, be awful. And so, the, it's this really interesting juxtaposition I think between like interior pain because all of that's happening like on the inside and then exterior self-fashioning that I think really, I, I don't know for me is you can look at images, right? Of like people, and I think Angela Ellsworth uses the body a lot and her work with her performance art that I talk about later on. But I think in this way there's a really beautiful kind of like I don't know, salience to like absence. Not being there and an object standing in for a human, right? And I think that [00:56:00] participates in like these larger kind of like, within feminist art in particular of the objectification of the female body.

Conversations around that, right? Through like maybe thinking about like the male gaze that we get in like the nineties with Laura Mulvey and things like that. But I think just in, in general, you know, letting these bonnets kind of stand in for humans, through is, I don't know, like a very emotional, at least for me, it was a very emotional encounter that felt. Very familiar as someone who grew up in the LDS church, where I always felt like, and I was always commented on for like the way that I dressed when I was younger. I remember like dating a guy, and going to church with him once, and him and his friends looked up like a passage in the Book of Mormon that talked about modesty.

And they were like, your shirt is like, the sleeves are not [00:57:00] long enough. And so like, I think fashioning and clothing, I mean like, which I broke up with him for, you know, like that was like, like we're not dating anymore. But also, it was really an interesting way of thinking about the ways that women body, women's bodies have been policed through clothing within the religion. What modesty kind of might mean in some form or another through that lens. And I think that like. I don't know. This absence that we talked about with Mary, you know, too is like maybe a self-reflexive, form of showing how present that absence is. Right? I think it's a really interesting strategy, you know, to render absent through the presence of something else, right?

To make it that this is actually absent.

Jenny Champoux: I just think that piece is so powerful in the way it expresses, like you were saying, [00:58:00] the interior pain, but the exterior beauty

Mary Campbell: Hmm.

Jenny Champoux: especially the way the whole, the whole piece is sort of about women's bodies, right?

And, and the way they're used or made to put on certain clothing or meet a certain modesty standard, like you were saying. And yet the body isn't there, right? There, it's just the bonnet. There's the absent body, but there's the idea of the body very strongly, even though there is no body.

And then just the materiality of it. I mean, I just, I haven't seen it in person, but just looking at the photo, I want to run my hand over those pearl beads on the top of the pins, on top of the bonnet. And I even, like, I want to touch the inside. There's something that feels like I want to engage with it that way. It, it encourages, I think, in the [00:59:00] viewer a very embodied response. Which, again, is like this really, really cool dynamic of the way it's making a comment about bodies and embodiment by the way it revels in materiality and the way it encourages that embodied response from the viewer.

To just transition back to Menachem, we talked in our first episode about an Art and Belief sculpture by Trevor Southey. Terryl Givens talked to us about the materiality of this bronze sculpture being an important part in a similar kind of way that the materiality was important to its meaning. I see that in some Art and Belief works, although to me as an art historian looking at, you know, the images in your chapter, I feel like stylistically they're kind of all over the place, right?

There's abstraction, there's expressionism, there's just kind of [01:00:00] whimsical sculpture. Sculpture and mobiles, and then there's like these really precise geometric approaches. So, do you feel like you can pin down a style for this movement? The way we might say, oh, I know what impressionism looks like? Can you say that about Art and Belief or, or if it's not a style, what is it that sort of holds this group together?

Menachem Wecker: I think impressionism is interesting too because who is Impressionism and who isn't, and what, like, when does Impressionism stop and post-Impressionism start? You know, I don't know. When does Impressionism start? I think it's pretty clear that Pissarro is impressionist. He was, I think, the only one who was in all of the, you know, impressionist exhibitions. But if we, you know, if we look at who's in and who isn't, it's often hard to determine.

What I came around to seeing is that there are certain characters and certain scenes that seem clearly to be Art and Belief. And in the way I was saying before about my 3-year-old saying, well, what isn't Art and Belief? Like determining what's in and [01:01:00] what isn't in is a complicated thing.

I don't know how much we need to know precisely what the contours are. And I, again, the earnestness or ambition or wanting to be firmly rooted in these two worlds at the same time, those, to me, those were the more important things.

Clearly Dale Fletcher and Trevor Southey and the two Smiths—Gary Ernest and Dennis—are, you know, are Art and Belief. Art and Belief is clearly tied to BYU. It leaves BYU at some point and either remains Art and Belief or becomes something else. And it, you know, it, it kind of moves somewhere else.

It gets tied to, you know, this concept of Eden in a kind of way. So, for some people it's just those four. Just at BYU there's various other people who are coming to meetings who are writing about it. Some of them describe themselves as flies on the wall. Some of them describe themselves as part of it. Some of the principals seem to think that those other people are in or are not in. Some of the principals seem to think [01:02:00] that at least one of them seems to think Art and Belief still continues. Now, the other one doesn't.

The lovely thing about the people I talked to, and I talked to a bunch of people who didn't make it into the chapter, you know, at all, but were really helpful and informative. Like some of the people, there was a lot of disagreement amongst the people I spoke to, and there was a lot of disagreement when I talked to people multiple times between sometimes what they had told me the prior time. So, I think the most fascinating thing about this is that it is a live complicated question.

And when you have people who are, we're making new work now, but saying they're inspired by it. Well, is that part of the movement? Is it inspired by it?

Yeah, I think with this movement, what's interesting is the four principals are men. Some of the people who are doing the most work and thinking that I talk to curators, museum directors, historians are women now, and I think that's interesting. The first wave, if there is a wave, seems to be largely men also, but that, that changes as [01:03:00] time goes on.

You mentioned stylistically and I don't want to dwell too much on style because I think what binds them is less style. I mean, you know, Dennis Smith is doing things that are so different from what Trevor is doing. But the, if I had to say it was most like something I'm familiar with, I think I would look to Pre-Raphaelites probably in terms of, of both kind of, the mark-making, but also the kind of way that they're looking to earlier traditions but also thinking in a spiritual way. It's not nearly a perfect comparison and there's a lot of differences, but if I had to think about a group also that has enough elasticity and room for variety, but still a kind of common direction they were going in, that's probably the one I would think the most about.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. You know, it's interesting that you mentioned, at least the first group was all men. It seems like most of the successive waves have been mostly men also. Lee Bennion is, I think, the only woman artist who I see associated as part of this [01:04:00] tradition. I don't know, I'm speculating here, but maybe that has something to do with why it never really got off the ground because there weren't enough women working with them. I don't know.

Menachem Wecker: Well, I'll just say the former director of the Springville [Museum]. She just, when I talked to her, I think she was the director and now she's not. Rita.

Jenny Champoux: Rita. Rita Wright.

Menachem Wecker: Like she's someone who was great to talk to because she was there. I don't know if she would just, I don't remember if she would describe herself as part of the movement or someone who was in the room often.

But she taught me quite a lot about the movement and I would have difficulty saying, even if she wasn't making works like the four of them were at the time she was there and part of it.

Jenny Champoux: Okay, so we're going to end as we do every episode. I want to ask each of you to share an artwork that is meaningful or interesting to you. Mary, can we go to you first?

Mary Campbell: Yes, absolutely. Thank you. So again, I'm quite torn on this front because there are so many that are meaningful to me. But I think when it comes down to it, if I [01:05:00] have to pick one, it's this stereoscopic portrait. So, a portrait that becomes three dimensional in the right viewer. And just to double check I want to say that it is from 1899, and it shows all of Brigham Young's surviving widows.

And it's a moment when these women are dying. So many of them have died. Some of them in the stereo view are about to die and it's right before we turn to the next century. And, and to see these women and to see them in three dimensions, to see them really embodied, looking at the camera and really declaring their own presence, right? Sort of what, Young, for whatever reason, would never document, would never put into visual form to see them [01:06:00] all lined up, sitting and standing, addressing the camera, right? For, for their own audience and their own kind of posterity I find just to be so terribly moving and beautiful.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah.

Mary Campbell: I think I'm gonna have to go with that one.

Jenny Champoux: I love it.

Amanda, can you share your work with us?

Amanda Beardsley: I mean, I always go back to these works in Jenny Reeder's chapter, the hair art, like, I just, it's so creepy to me, but also so beautiful. You know, it's like 19th century hair isn't, is, you know, not specific to Mormonism, but the way that these women kind of took their hair and turned them into these sculptural pieces, takes on, I think, a different tone within Mormonism when you think about genealogy and specifically kind of the bodily implications of presence in those, right? And I think it takes a from that, like memento mori kind of like thing, right? [01:07:00] To where I can like look at something and it'll allow me to remember and assert that presence in a very similar way to, I think what Mary was saying, right? Like where it's like we have this three-dimensional assertion of presence.

And then for us, we have this material assertion of presence with hair. And that was, you know, hung in the temples and Mormon temples, you know, in the 19th and 20th centuries. And so, I love the way that Jenny writes about those, and I just can't get them out of my head. And I almost wanted to make some, when my mom passed away this year, I wanted to make like, hair art from her, you know, like, it just, it, it resonated on so many beautiful levels.

Jenny Champoux: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Yeah. Yeah, those were so fun to learn about and I feel like not something that is really well known in Latter-day Saint visual culture today. So, I really appreciated that recovery of the history there. Reintroduction of that. Thanks. [01:08:00]

Okay, Menachem. Can you share one with us?

Menachem Wecker: I can, I'm going to continue to not live up to the questions and I don't know that I know enough. I don't know if I have enough of a kind of a body of art from the Church in my head that I could pick a favorite. I'm going to share two, and if we put the two together, it might answer your question.

So, one of them really quickly is, you know, I went to graduate school and worked for about five years at George Washington University, nearby in Washington, DC and I was always struck that, particularly around graduation time, all these students come and pose in front of, I think there are five of them, enormous sculpted heads of George Washington, on campus. And I don't think anybody pays any attention to who the artist is. And if one goes and looks, it's one. I hope I pronounce his name right. Avard Fairbanks. Is that how you pronounce his first

Jenny Champoux: Yeah.

Menachem Wecker: And there's a whole fascinating story people can look into about how these got to GW and there, you know, we talked about law and art before, there is some room for things that the IRS maybe should have been investigating on this, but it's fascinating. They all get [01:09:00] there and I don't think anybody makes the connection. These works are not, you wouldn't call them religious particularly, but when one goes to Temple Square and sees all the sculptures there, one wonders if all of his work is not infused, you know, with at least some faith angle.

But I don't think most people put two and two together when they're driving in the DC area and see the temple in Kensington, Maryland and think that the Angel Moroni, on the spire I think is also Fairbanks and, and don't draw that kind of a connection. So that's one thing I think about sometimes how works are kind of hiding in plain sight. That people don't think about.

Another work that's not from the Church but I think conveys something that I find really interesting about art in the church is one of my favorite paintings that's in Vienna at the Kunsthistorische Museum is a work by Jan Gossaert, who went by Mabuse. I think his, I think the work was about 1520, give or take five years on either side.

And it's a St. Luke painting the, drawing the virgin. And it's a [01:10:00] wonderful picture if people haven't seen it. The saint is kneeling there, and he's got like his work and he's drawing it. There's the virgin and child kind of encircled with clouds, and there's an angel who's guiding St. Luke's hand and high up tucked on a shelf is a little sculpture of Moses with horns due to the misinterpretation of the Hebrew word, which meant that his face was illuminated rather than horned.

And he's pointing to Ten Commandments that he holds in his hand, particularly the second commandment. And I love this work because this is the Catholic moment that you know that the angel is saying to Luke, don't worry about those Mosaic Ten Commandments that say don't make idols. It's okay. You can draw this virgin.

So that to me was always interesting, kind of an artistic depiction of permission to make sacred art and that it wasn't going to be idolatrous. The thing that's fascinating to me about artistic tradition in something like the LDS church is that what does it mean for artists when you have more or less a pretty good idea of what a prophet looked like?

[01:11:00] Like what does that do for questions of idolatry? What does that do to the kind of way that people create biblical figures in other traditions, in their own images over the centuries? I just think that is a fascinating thing that is rather different, you know, in some art that's part of the Church and, and other traditions and I, you know, I don't know what to make of it.

I just think that's a fascinating thing that comes up that is, you know, that's part of these larger body of fascinating questions about sacred art.

Jenny Champoux: Wow. Those were amazing examples and really gave me a lot to think about. I think there's a lot more to explore there. I love that you just opened up this whole discussion that I want to think about more now. Thank you.

Menachem Wecker: Next, next podcast.

Jenny Champoux: Next time. Yeah.

Amanda Beardsley: Menachem, I think you and Mary should have a podcast though. The two of you

Jenny Champoux: Yeah.

Amanda Beardsley: That was really fun

Menachem Wecker: I'm not used to answering questions, though, I have to be asking them. So.

Jenny Champoux: Amanda, Mary, Menachem, thanks for talking with us today!

Menachem Wecker: [01:12:00] Thank you.

Amanda Beardsley: Thanks so much, Jenny.

Jenny Champoux: To our listeners, thanks for tuning in. Join us on the next episode where we'll build on this discussion and dive into questions of race and identity in Latter-day Saint history and art. We’ll be joined by scholars Paul Reeve and Carlyle Constantino. We'll see you then.

Thank you for listening to Latter-day Saint Art, a Wayfare Magazine limited series podcast. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Art. I hope you'll order a copy of the book to read the full essays and see all the gorgeous full color images of the artwork.

You can learn more about the book and other projects at the Center's website at centerforlatterdaysaintarts.org. If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to listen to the other episodes in this series. You can subscribe to Wayfare Magazine at WayfareMagazine.org. And thanks to our sponsor, Faith Matters, [01:13:00] an organization that promotes an expansive view of the restored gospel.

If you'd like to learn more about Latter-day Saint art, check out my other podcast, Behold: Conversations on Book of Mormon Art. You can also learn more at my website, The Book of Mormon Art Catalog. With more than 11,000 artworks, it's the largest public digital database of Latter-day Saint art. You can search by scripture reference topic, artist, country, year and more.

And we recently added a new section for art based on Church history, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. The website is bookofmormonartcatalog.org. Check it out and see what exciting new art you can find to enrich your study.