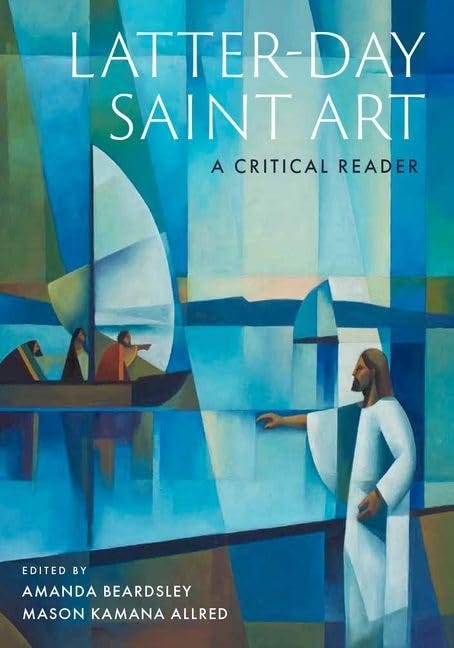

Jenny Champoux: Welcome back to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux. In Latter-day Saint Art, I'll guide you through an examination of the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts.

In this second episode, we look at some of the earliest Latter-day Saint art from the 19th century. It's going to be a fun mix of mediums and styles as we discuss paintings, sculptures, cartoons, quilts, and even commemorative designs crafted out of human hair. We'll consider the ways these early artists were navigating a pull between the individual and the community, how they used art to announce their respectability to the world, how women used domestic crafts to visualize belief and shape identity, [00:01:00] and how art was displayed in the earliest temples.

Our guests are Ashlee Whitaker Evans, Nathan Rees, and Jennifer Reeder.

Ashlee Whitaker Evans is the former head curator and Roy and Carol Christensen Curator of Religious Art at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art. Prior to that, she was associate curator and registrar at the Springville Museum of Art. She is an alumna of BYU, graduating summa cum laude with degrees in art history and curatorial studies. Her research interests span religious art and visual culture, as well as western regional American art. Ashlee has curated numerous exhibitions, including Rends the Heavens: Intersections of the Human and Divine, In the Arena: The Art of Mahonri Young, The Interpretation Thereof: Contemporary LDS Art and Scripture, and Moving Pictures: C. C. A. Christensen's Mormon Panorama. Her chapter in this new book [00:02:00] is titled, “Establishing Zion: Identity and Communitas in Early Latter-day Saint Art.”

Our second guest, Nathan Rees, is an Associate Professor of Art History at the University of West Georgia. His research focuses on the intersection of race and religion in American visual culture. He has published and presented on topics ranging from the influence of metaphysical religion on 20th century abstractionists’ encounters with Native Americans, to the representation of race in the visual culture of Southeastern shape note hymnody. He is the author of the book, Mormon Visual Culture and the American West. And his chapter in this new Latter-day Saint art book is called “The Public Image: How the World Learned to See Mormonism from Cartoons to the World's Fair.”

And then finally, we'll be joined by Jennifer Reeder, who is the 19th Century Women's [00:03:00] History Specialist at the Church History Department in Salt Lake City, Utah. Jenny has co-authored three collections of women's writings and written a narrative history of Emma Smith. She grew up playing under the quilts her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother sewed, and she has an innate interest in folk art. At George Mason University, where she earned her Ph.D. in American History, Jenny studied religious history, memory, and material culture. And her chapter in this book is called “Creating Something Extraordinary: 19th Century Latter-day Saint Women and Their Folk Art.”

I've known our three amazing guests for many years, and I know from experience that they are brilliant, dedicated, and generous scholars. You are going to love hearing from them today.

Ashlee, Nathan, and Jenny, thank you so much for being here!

Jenny Reeder: Hello

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Thank you.

Jenny Champoux: What a treat to have such a powerhouse group with us today. [00:04:00] I'm really excited to dive into early Latter-day Saint art of the 19th century with you. I've already given our listeners a little bit of background on you and your scholarship and professional work, but I'd like to give you a chance to tell us a little bit about yourselves. Ashlee, let's start with you. You recently helped curate a really important exhibition at the Church History Museum on Latter-day Saint art. How did your work on that exhibition inform your scholarship in this chapter? Or maybe vice versa?

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Yeah. That's a great question. And just to start off, a wonderful nod to the center for Latter-day Saint Arts, because I feel like we were all part of this book and that preceded the exhibition, but just a little, they had the vision of creating this unprecedented publication of Latter-day Saint Art.

And then, shortly thereafter, it felt [00:05:00] like, they approached myself and two other just outstanding art historians about doing an exhibit, also kind of an unprecedented scope, looking at Latter-day Saint art, and one of the things that really felt important was to root it thematically. Not necessarily chronologically, not linear, but thematically. And the reason for that was we felt like it was really important to allow for the values and kind of the, some strong beliefs of the Latter-day Saint people to be the framework in which we look at how these have been manifested over time, over countries, continents, genders, that type of thing. And I think similarly, my thought process as I was approaching my chapter in particular, which, is the more traditional art media of the 19th century. I really kind of kept coming back to this idea that [00:06:00] at least for me to look at this media, there really needed to be a strong foundation and understanding at the core, who the Latter-day Saint people were, and most particularly in context of what I wrote is how deeply the idea of covenant identity of a people that were, you know, Zion, that were seeing themselves as a modern day Israel were.

In informing portraiture, landscapes, and genre scenes, etc. And so in that way, I, it just felt like characterizing and putting the artwork in context of values, beliefs, and even discussions of doctrine felt like a really important framework.

Jenny Champoux: I had a chance to visit the exhibition out there and just loved it. It was such a fantastic juxtaposition of really iconic pieces, [00:07:00] plus stuff maybe we're not as familiar with that we don't see as often. Old things, new things, things from America, things from all over the world, from members globally.

And it just, it was just gorgeous and really gave me a lot to think about. So great work!

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Good, good. That was our hope. That was really our hope.

Jenny Champoux: Thanks. Okay. Nathan, when we think about Latter-day Saint art, probably for a lot of people, the default is to think about paintings, right? Your chapter deals more with cartoons from 19th century and monumental sculptures. What drew you to thinking about those different types of media? And do you, as an art historian, do you read those kinds of works differently than you would a painting?

Nathan Rees: Yeah, so there's kind of two answers to that question. And the broader answer is that I'm interested in visual culture beyond just what we might think of as art history. And I [00:08:00] think that's something we have in common, actually, with several of us that worked on this project. So the idea with visual culture is that you are interested in how people communicate through images. And you don't really pay as much attention to the hierarchies of like which images are maybe more important. So to me that really just expands the whole range of what we can actually think about as important images to consider and that's not to say that you don't employ all of those methods of art history as well, too. So visual analysis is super important. Thinking about how all of these creators whether they thought about themselves as artists or not, used the formal elements of art to actually communicate what they were trying to get across. That's a really important piece of visual culture analysis. So that's like the method. The question about why these two things because that is a little weird I know to have like stuff that's just ephemeral and then like giant monuments. But to me the [00:09:00] connection is that it's all about audience. So we're thinking about things that were made to be public, although they're very, very different in terms of their modalities, their materials, they both have that in common, that these printed things were disseminated widely. Monumental displays or monuments were things that people would just see out in public. And so not only they had that broader audience, but the people who created them were thinking about this as something that is reaching this much broader audience than what we have, for instance, a painting might have achieved at the same time.

Jenny Champoux: That's really interesting. I'm always a big fan of when a scholar can bring together two seemingly or totally different things and find interesting connections. And you certainly did that in your chapter. So well done!

Nathan Rees: Well, thank you. It's a lot of fun. I appreciate it.

Jenny Champoux: Okay. And Jenny Reeder. I think most of our listeners will be familiar with the amazing work you've been doing [00:10:00] to recover and catalog the history of early Latter-day Saint women. You've published on these women, you've published their collections of writings. Here in this book, though, you're looking more at the material legacy. So, I just wanted to ask, is that a very different project for you, looking at, instead of writings?

Jenny Reeder: You know, it's actually the material culture that has brought me to the writings. I've always been interested in quilts. I wrote a master's thesis in a human communication program at Arizona State about quilts as memorials and I also curated an exhibit at BYU in their special collections on how Mormon women have collected and preserved their past. So that's what actually drew me to the history, the written work. I wrote my dissertation on [00:11:00] extraordinary objects and Mormon women in the creation of a usable past. So each chapter looks at a different item or artifact that remembers and commemorates the Nauvoo Relief Society. And it was a lot of fun. So I, of course, had to do quilts and other things similarly, and I'm working on publishing that dissertation, but that's what brought me so easily and quickly into this world.

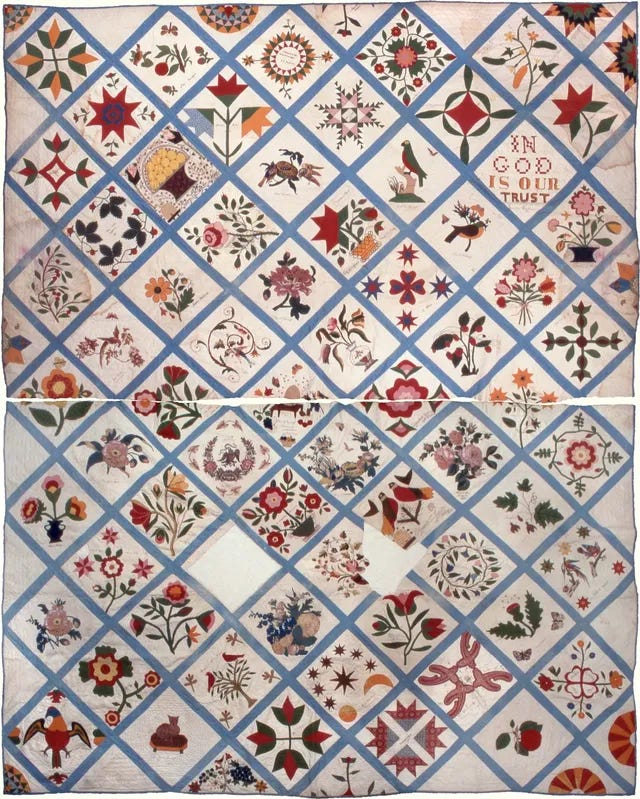

Jenny Champoux: Oh, that's wonderful. Yeah. I think that's great too. That there's that crossover between those different types of things that have been left to us from the past, so, thank you.

Jenny Reeder: Absolutely. Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: I loved these 3 chapters as I read through them. I saw really 4 themes that stood out to me that I saw kind of repeating across these 3 chapters.

And I think that's going to be a helpful way to organize our discussion today. So the 1st theme is, is that 19th century Latter-day [00:12:00] Saint art often exhibits a tension between the individual and the community. So we'll just go back in order here. Ashlee, you could start us off. Can you share an example, each of you, from your chapter that illustrates this dynamic between the individual and the larger community?

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Yeah, totally. So I'm going to be a little bit of a hog. I'm going to, I want to give an important nod to one work and then talk about a second work. So I, as I was thinking about this, there is this incredible dynamic that Jenny's just described. And I think one of the most outstanding examples of it is also one of the most well recognized works of art of the 19th century, and Nathan and Jenny have both written extensively about this, but it's C. C. A. Christensen's Mormon Panorama. And, I mean, for those that are familiar with Latter-day Saint art at all, it's probably the most iconic work of that era. Of that century, that time period within our church, and it does an [00:13:00] incredible job of showing of showing how the Latter-day Saint past and the traumas and the miracles experienced by that first Pioneer generation could be experienced and felt by subsequent generations because C. C. A. created a panorama format.

To immerse his audiences, whether they've experienced it or not, into these moments to truly transport them and create a highly emotional event. So that, that just feels like it needs to be mentioned. It's so signature.

One piece that I thought was really interesting as I researched that it doesn't have the same notoriety, but I think is so, so poignant, was actually created by a different artist, George Ottinger, and he's a really fascinating 19th century artist.

Super interesting. His teen and youthful years read like a novel, but long story short, he ends up [00:14:00] leaving a career and hopefully sailing, joining the Church back East with his mother and they travel across to Utah. And as they travel, it's in 1861 in the Milo Andros, Andrus, sorry, pioneer company--he paints scenes on the trail and it's very rare to see those, actually, so his documents, I call them documents, his paintings are documents, really unique, and what's beautiful about it is they're rather modest in scale, maybe 17 by 23, but there's a painting that I focused on called The Burial of John Morse, is what Ottinger titles it, but it's really John Moss, and it shows a gentleman who traveled as, based on sources, traveled alone in that pioneer Company.

He was from England. And he was buried on July 25th at nighttime along the trail. [00:15:00] And you see the burial party up on a bluff. It's a nighttime scene again. And the wagon train is on the plain below the bluff and there is a sacred sense of light emanating from the very small body of the figure that they're about to bury.

And there's just a halo of light around that burial circle. And that's echoed in the halo of the white canopies of the pioneer train. And it just invokes this sense, I think of the individual kind of the shared experience that the Latter-day Saints, as they were having this exodus to the West.

They were truly leaving what they knew they were becoming a people set apart in a physical as well as a spiritual sense. And that, you know, one death of the community represented a sacred consecration, really, that impacted the [00:16:00] whole group, but also spoke to, I think, the very strong motivations of faith that were governing the Latter-day Saints actions at the time.

It's a beautiful memorial painting and I think really evokes that sense of, that kinship that was being forged as they went through these events together.

Jenny Champoux: Yea, so that’s great. It’s a perfect example because it’s this one person, memorializing this one person, but then kind of generalizing it to the larger pioneer experience that so many went through. Yeah, thanks, Ashlee. All right, Nathan. What examples do you see of this?

Nathan Rees: Yeah, thank you. This is such an interesting question. And with public art, that's also a critical question because the idea is that this is not just one individual person's statement. It's like supposed to be the community speaking. So then how does that artist have to negotiate maybe their [00:17:00] specific perspective with a way of trying to describe something that's broader about their whole community? And then that got me thinking too about like, well, who exactly is the community? And I was thinking about an example that took a lot of negotiation that is something really fun also that I learned about and I wish it still existed. I think somebody needs to figure out a way to recreate this, it was called the Utah Exposition Palace Car. So it's like a rail car. It was donated by Union Pacific. It was sponsored by the Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce. The idea was they had Utah artists, and it was run by an artist named Henry Culmer, but they had Alfred Lambourne, John Tullidge, and Dan Weggeland, painted landscapes of Utah, and then also like all the different crops you could grow in Utah. Then when you went inside the car, they had expositions about various kinds of agricultural, industrial, mineral stuff that was going on in the state. And then the car actually got [00:18:00] like taken from city to city across the Midwest and to the East. And, you know, people could come to the train station and if they're like, just waiting on a train or whatever, it's like, Oh, come stop into the Utah Palace Exposition Car. So people did. Apparently 190,000 people, at least according to Henry Culmer, visited this thing and he went along with it. And so it's really interesting to think like, so how do you represent Utah? If this is on the one hand, mostly Latter-day Saints that are producing, doing art for this, trying to self promote, it's an era right before the manifesto.

So there's like a lot of need to generate some goodwill about Latter-day Saints, but it also can't really just be that because this is the Chamber of Commerce. It's Union Pacific. It's got to be something that's this broader community of Utah. So it's interesting to see that kind of negotiation in the way that that car, it alludes to the successes of Latter-day [00:19:00] Saint settlers, it doesn't really quite actually have anything that you would identify as like, Oh, that's Mormon. But in 1888, like everybody, as soon as they saw the word Utah was like, Oh, Mormon. So it was complicated. It's interesting to hear some of the voices from, from people back then.

And so Culmer, he was really adamant that like people come see this. And so his quote was he wanted to impress upon the public that life and property are safe in Utah and that the Mormons are not heathens. That's his quote. But then at the same time, a Jewish businessman named Fred Simon, who was going to become the Chamber of Commerce president a little bit later on, so he was heavily involved in that. He wrote that, quote, while religious and political differences exist, they are being obviated as quickly as circumstances could possibly permit. So you've got all these different people making up this big kind of conglomerate community trying to figure out how to [00:20:00] like, arrive at one kind of representation that's going to satisfy everybody. Pretty big idea to try to, to, to get that. And make it work. And it seems like they did.

Jenny Champoux: That's amazing. I had actually never heard of this rail car before. So I really enjoyed reading about that in your chapter.

Nathan Rees: Yeah. I wish it was still around somewhere.

Jenny Champoux: I know, wouldn't that be fun to see?

Okay, Jenny Reeder, are, what's an example you see of this individual and community dichotomy?

Jenny Reeder: It's so interesting to me to hear both from Ashlee and Nathan, because I feel like the work that I've done goes right in the middle of all of that. So, two formats that I look at in this chapter are extremely traditional and popular during the time. Even though we don't particularly relish hair art as maybe they did in the 19th century, it was a very popular [00:21:00] thing. And it's interesting to see the piece that's hanging up in the exhibit. And also the, one of the pieces that's featured in the chapter this beautiful, it's, I think it's even more beautiful if you don't know it's hair, but since it is hair, I think it's, it's incredible the work that, how they were able to be so resourceful with something so readily available. And they did this piece for the Manti Temple and it's a, it's actually a, there's a wood chip a tub or font where they did baptisms for the dead. And then coming out of the font is this beautiful different kinds of flowers and plant life coming out of it. And it's, it's something that was typical for the time.

And yet it's so distinct for a Latter-day Saint population, particularly a temple viewership, where only worthy Latter-day Saints could enter. But it reflects [00:22:00] also their understanding of ordinances and of the plan of salvation, of baptisms for the dead and all these other things. So it's a really beautiful piece in that sense.

There's another piece that I look at in the chapter that's very defined as to who is, whose hair is where, and it's much more hierarchical. This one is much more democratic and universal. It doesn't tell you whose hair is where it's just the hair of the women of the Manti North Relief Society. So I think that's really interesting. They are trying to use something that's a, it's a symbol of refinement that time period. And yet they're tweaking it in a way that displays their own doctrine and thought and theology. Another piece that I think is really interesting is, is quilts. And now in the exhibit, there's this beautiful Salt Lake City 14th word quilt. And in my chapter, I look at the Salt Lake City [00:23:00] 20th word quilt and quilt is probably the most universal American symbol of women and domesticity and refinement. And it's so interesting, I think, though, to look at these pieces and to see who these women were and why they did what they did. In both the 14th word quilt that's on exhibit and the 20th word quilt, each block represents a different woman.

So each one quilted her own block and then they put it all together. In the 20th ward, it's so interesting. This is a ward that wasn't one of the original 18 wards in Salt Lake City. This is a ward that comes a little bit later. So the people that live there, it's on the Northeast side of Salt Lake City. So where the Avenues are now and the people that have come to live there, a lot of them are international. So Denmark and Sweden and England and Scotland and Ireland and all these other places. Now this quilt was made in [00:24:00] 1870, which is significant. Because earlier that year, in January, February of 1870, the women had what they called the Great Indignation Meeting, where they all met in the tabernacle, there were only women there, there were no men, even reporters, only women reporters, and they, it was the first time they really gathered publicly to speak publicly, and their topic was religious freedom, a.k. a. Defending the right to practice plural marriage.

So it's a, it's kind of a weighted topic, but these women are so anxious to be able to worship as they choose and to make that message go across. Now, I also think it's interesting because many of the women that made that 20th word quilt are not English speakers. And so being able to make something or create something visually is much easier for them. And [00:25:00] some of them do motif, nature motifs or flowers or something that represents their country or their cultural, cultural heritage, but then others transcend that and do something that represents woman's suffrage or refinement and domesticity, like the fruit that they grow and the things that they do. It's, it's really interesting to see that all together in one place.

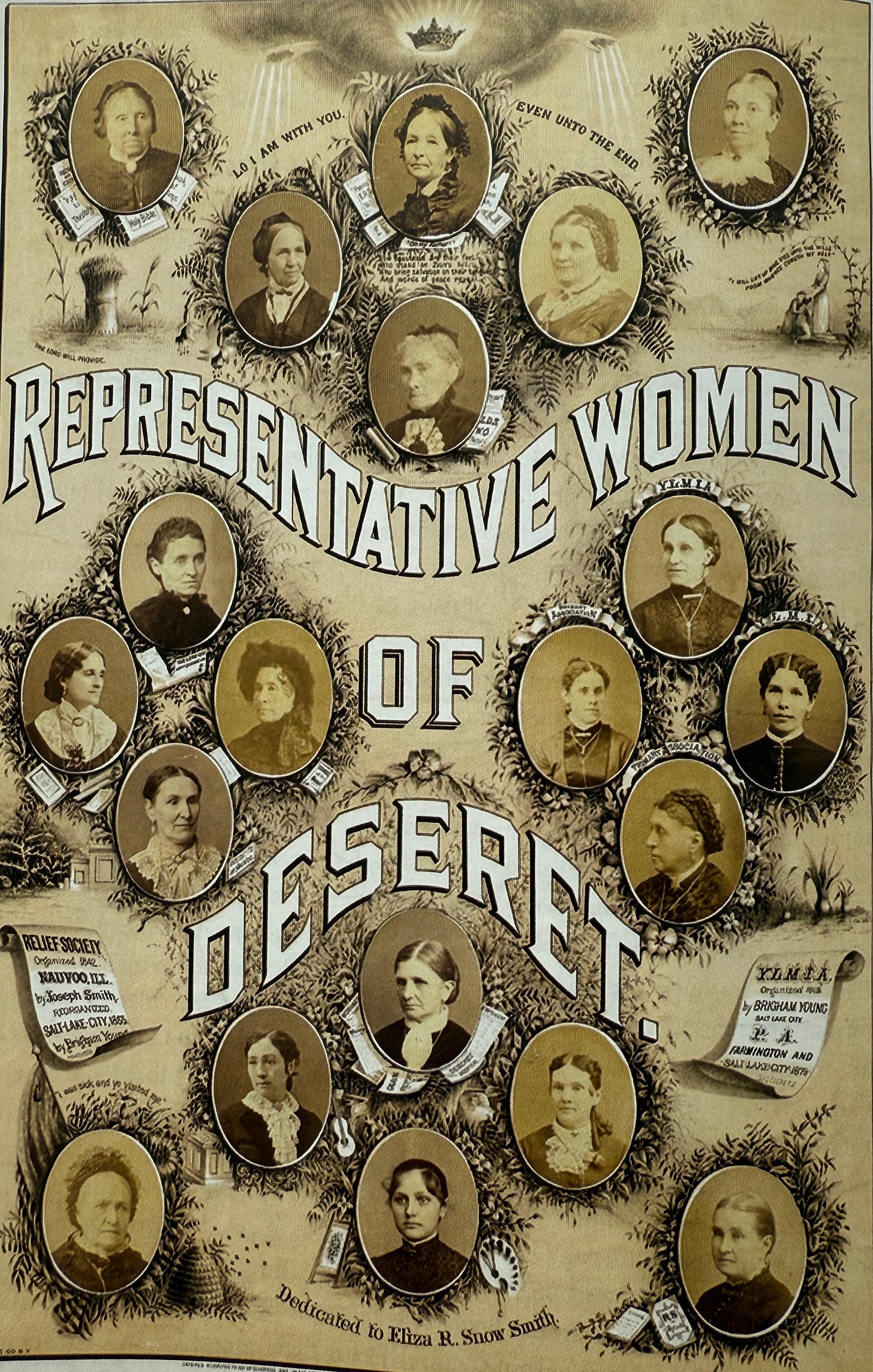

But Nathan, I think you had a really interesting point in your discussion of the need for Latter-day Saints to display in contrast to what they thought other people were thinking of them. So also during this time period, you have a lot of the cartoons of women, particularly in Utah, of Brigham Young's wives, and they're all in bed with them, or the harem, or whatever it may be. And so I feel like they are trying to display themselves or market themselves in a much [00:26:00] more broad way. So the poster that I, I'm so interested in is called the Representative Women of Deseret and it is incredible. They are taking the, the photographs of each of these leading women. So there's clearly a hierarchy in this poster. They have them all cut out in little ovals and then Augusta Joyce Crocheron takes them and illustrates them in ways that represent the women. So there's a lot of little things. Eliza R. Snow has, for example, Oh my father right underneath her and she's at the very top, a very prominent position. And there's a crown at the very top with rays of light streaming down from heaven. And so what I think is going on here is these women are trying to project themselves as refined, as educated, as talented, and civically involved. And this is their way to do it. [00:27:00]

It wasn't a hot bestseller, poster. I think there's actually only one of them that exists today that has Oh, no, there's two, because one of them actually, and maybe this is significant, it's in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. So that's a pretty nice audience, right? The other one's in the Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum in Salt Lake City, but it's a, it's a fun little piece.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, thank you. I loved seeing this in the book too. And what you're saying here is bringing me actually to our second theme that I noticed, which is this need of the saints in the late 1800s to project this sense of respectability. And, I mean, they had come through this moment where they were pushed out of American society and fled and went to make their own society in the wilderness. And now they're at a point where want to look like [00:28:00] good citizens. Let me start with Nathan here. Can you just contextualize a little bit about that? Why there's this shift and what are some of the ways that the early saints are using art to try to announce themselves as civilized Americans?

Nathan Rees: Yeah, it's, so it's complicated. But, one piece that stands out to me as really an iconic representation of this idea is the Brigham Young monument that was commissioned from Cyrus Dallin, to be placed in the just like absolute center of Salt Lake City. And it's, so it's another example of collaboration that wasn't entirely done just by Latter-day Saints. It was also supported by variety of other Utahns at the time to be kind of a big point of civic pride. It's very, surprising, really, if you look at where the Church was financially, where Latter-day Saints were financially around 1890, that they would be in a position, they're really not in a position [00:29:00] to spend tons of money that they have to mostly just self-fund to create this gigantic monumental thing. It's also really important to them to all of these images. I mean, just looking through the anti-polygamy cartoons and caricatures and everything else. And then, you know, let alone the things that are being written and published, they felt like they were not representative of who they really were as people. So they tried to find ways to showcase their refinement and sophistication. What better way to do that than with a giant monument and this is also really, I mean, in an era where you don't see that, if you were going to, especially in the Western United States, that really would have stood out as, as something surprising and sophisticated.

Cyrus Dallin was a Utahn. He had gone back East, gotten a bunch of attention there. So it was also kind of a point of civic [00:30:00] pride that they were able to produce someone with this artistic talent from within their own community, although he wasn't a Latter-day Saint himself. He purposefully modeled this after a monument in Paris that had just been erected about five years prior. So another kind of connection, it's like, you know, we're right behind Paris here in Salt Lake City on this world of refined, high quality works of art. Everything about that monument as a work of art, but then also just the way that it represents Brigham Young as a person who brought culture and civilization to, this, to their mind, completely uncivilized part of the world and whether you're a Latter-day Saint, whether you are another Utahn who just kind of like wants to get out from under the shadow of Utah being this kind of pariah state is territory at that time. That's a great way of saying, like, look, we've arrived. We have not only arrived, but we brought ourselves here. We brought this place [00:31:00] up. We brought civilization to the desert. And it's a pretty dramatic statement.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, it really is.

Ashlee, so I know we don't have really a lot of Latter-day Saint art happening until these last three decades of the 19th century. And especially religious art or art dealing with the history of the Latter-day Saint people. We start seeing that in the 1870s, 80s, 90s.

And, you know, at that time, there's this, you know, federal government is cracking down on cohabitation and polygamy. And there are you know, the, the Utah settlers are responding to that. And there's this push for Utah statehood. And so how, how does all that play into what you see happening in the way Latter-day Saints are projecting themselves in the art of that time?

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Yeah, I mean, it's such a dynamic period, and I [00:32:00] think definitely when you look to some of the landscapes, the genres, other scenes, but what's interesting to me is finding examples like, you know, Brigham Young's estate in Salt Lake City, where he's having it painted multiple times the same view, one of which we knew hung in his home over the fireplace, sort of showing his embrace of, this ideal of, ou know, cultivating the land, having a schoolhouse on your land, having working farms. It shows something to, for example, guests that might come to Brigham Young's home to see his landed estate from this view, where you get a picture of it. You know, a broader, more aerial type of view at the same time.

It's interesting going through some of the rhetoric of the time. The Church leadership would travel around the Utah territory, the Mormon corridor, and they would be preaching the ideal of, you know, it's your first [00:33:00] duty. In Zion to learn how to plant a crop to have an orderly, whatever your home is having the orderly plant trees.

I mean, those were recurring dialogues and admonitions to the people. And so it's interesting to see some of these landscapes in that context. Just knowing that there was not only a temporal motivation, of course, there was a communal motivation and a spiritual motivation that they, that they really saw, I think.

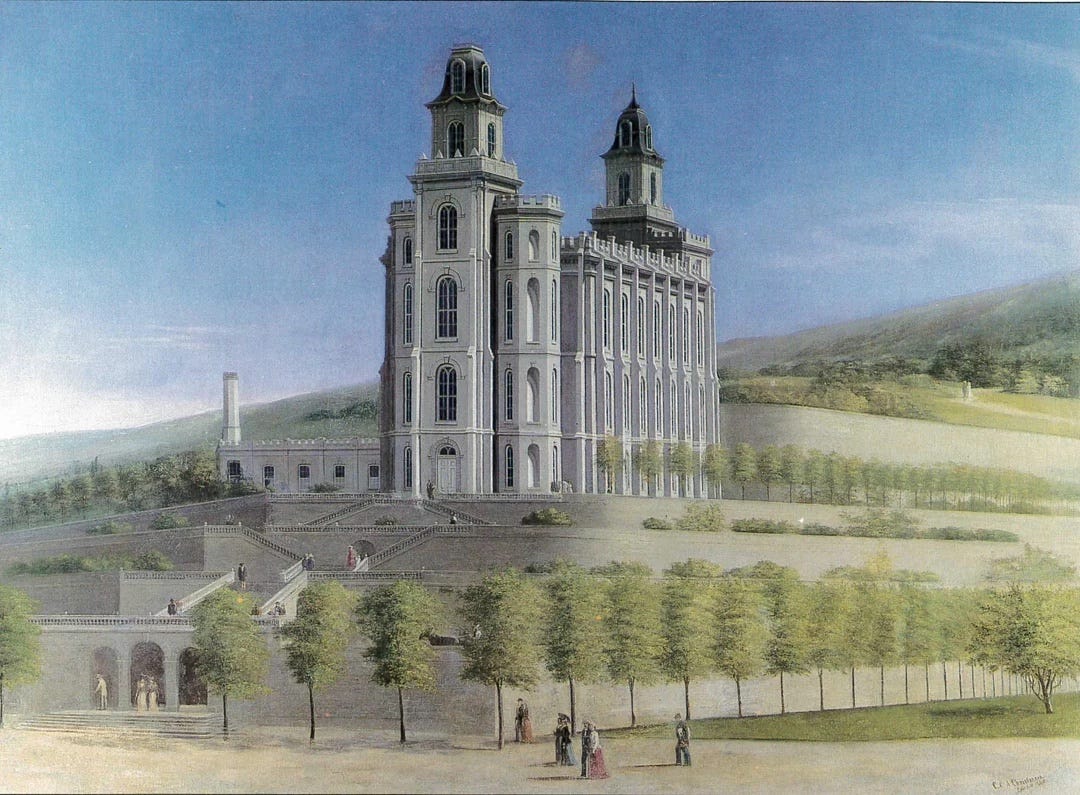

One painting that I really, really love that I think hearkens to this is by C. C. A. Christensen. So, I mentioned him before, but he's a Danish convert, and he comes over to the U.S. and begins painting, quite a bit in the 1870s and onward. And he paints a scene of the Manti, Utah Temple, and from the records that we have, it was actually commissioned by the Relief Society in Manti, so go Relief Society again. [00:34:00] But the temple has recently been dedicated in 1888. And it is an incredible structure in a relatively small farming community in Sanpete County, Utah, but it is, you know, a castle like structure that just vertically dominates it's surroundings, it's built up on a hillside.

He shows it as a very commanding way that the Latter-day Saints have taken this landscape, the home of indigenous peoples that they've, they've kind of, He's taking this land as a means of serving their great cause of building a temple to the Lord.

And he shows the terracing that was the original vision for the temple landscape. It's not really seen that way today in the same way, but it's just totally man made and altered. And it shows an impressive level of refinement, I think, and an [00:35:00] impressive architectural feat. And the commission, going back to that commission by the Relief Society, but the understanding is, through documents, that it was intended as a prospective painting for the Chicago World's Fair in 1893.

So this painting really was, perhaps more so than some of the other, you know, scenes of, you know, of homesteads or things really was intended for a broader audience and showing this impressive structure. The, my favorite part about this depiction is probably that you've got the temple, the terracing that leads up to it, and then you've got figures promenading around the temple. And I did my some of my graduate work in 18th century landscape gardens, and you would always see these landscape gardens portrayed with people, you know, pairs, couples promenading through and just scattered about showing the leisure. This was a [00:36:00] genteel kind of depiction. And so seeing C. C. A.'s picture there, it speaks in so many ways to this idea of portraying refinement.

That these are people that have the same kind of, you know, social aspirations as the outside world that have the same kind of refinement.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I just think this is such a great example of this. And like you said, it was specifically meant, you know, to send back East and say, here's, here's what's happening in Utah and isn't it amazing. And we've got these great structures and fancy people promenading on the terraces and like, Hey, we're just like you, we're just normal, civilized Americans out here in the desert. Right.

Um, okay. Let's continue with Relief Society a little bit, Jenny, and I was really fascinated in your chapter with, you talked about Relief [00:37:00] Society buildings and how this early architecture helped project the sense of refinement. Can you tell us more about that?

Jenny Reeder: Absolutely. This idea started in 1868, 1869, the Relief Society is, is growing once again. And Sarah Kimball had this idea. She was the president of the 15th Ward Relief Society. Had this idea to make a space, a location where the Relief Society could have their, their gathering place, as well as their workspace. So, there's a picture, and I love this photograph, of the 15th Ward Relief Society Hall. It is located where now we have the Delta Center. So I don't think they're going to want to move that to put up a replica of the Relief Society Hall, unfortunately. But it's, it's this really cool idea. She, in fact, she takes it, I think it looks just like, [00:38:00] the same format, the same construction as the Nauvoo red brick store where the Relief Society was first organized in 1842. So there's a store on the bottom and then there's meeting rooms on the top. And by this point in Utah, Brigham Young is really encouraging the women and particularly the Relief Society to make their own clothing and household needs to be able to rely on themselves as a distinct and separate and isolated people rather than really being involved with the mass transportation that's coming with the, with the transcontinental railroad and items from the Gentiles.

So it gave them this place where they could sell their wares and make money for them, for their organization and for their needs and meet. And when they started this place, they, they had a dedication ceremony. I mean, they used all the things that we do today for a temple and they [00:39:00] had a march where they marched from the ward house to the location and laid cornerstones. And Eliza R. Snow wrote a poem about how this was a place of science and of art. It's, it's really a great spot. And the photograph, if you look really closely, you can actually see two, Black people in there. And we haven't been able to figure out who they are, but, it's, it's interesting to see that. These, these Relief Society halls really became, I think, a permanent, well, okay, maybe not permanent, but for the time, because we don't have many of them today, but for the time they were a permanent fixture on the landscape in the settlements and sometimes the, you know, the second or third building, permanent building built they were able it's so interesting to look over time to trace the architectural designs and the features that they add on. [00:40:00] I was really motivated by Richard Bushman's book The Refinement of America because he talks about how through architecture and through the layout of a house or the placement of the garden or things like that that that people could project this idea that they were more.

It's the development of the middle class that they were more middle class verging on the upper class than they were lower class. And I think that's what these women were trying to do. Not only were they creating their own space, their own autonomy to make money and to serve others, but they were leaving their mark on the very visual front of the town or settlement.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, just amazing. I'm just so impressed that these women had the foresight and just the ability to get this done and to build these incredible spaces.

So we've talked about how the Latter-day Saints are sort of projecting what they want people to see about them in their art. But then the third theme that I saw [00:41:00] in all of your chapters was how Latter-day Saints are being perceived by others outside the faith that are sometimes in visual ways.

Nathan, you had a really fascinating comparison of two lithographs from the 1880s of Latter-day Saint women, one by somebody else, and one done by, within the Latter-day Saint community. Could you talk us through these two, and like, tell us a little bit about what they reveal, about how outsiders were seeing Latter-day Saints?

Nathan Rees: Yeah, sure. So the illustration I have is from a magazine that was published in New York called Chic, and the title of this little illustration is called The Elders’ Happy Home, and it has, I think, 10 women on this gigantic bed that are involved in a just complete brawl. They're fighting and pulling at each other, and it's just complete mayhem. The elder himself is up on top of a chest of drawers trying to like escape from all this [00:42:00] mayhem. And then there's a little, well, actually a very long crib with, I believe, 10 little babies who are all wailing as well, too. So it's just kind of one of a million different representations of polygamy that thinks of polygamy as a joke, that imagines this thing that is threatening and different and scary to a lot of Americans in the age of Victorian public morality.

It's just like, violates so much about their idea about what the household and the family should be like that a lot of people created these caricatures in response that are not really meant to be taken seriously. But you have to remember that behind that there's actually a lot of vitriol, that these like kind of ridiculous, absurd depictions are meant to be degrading about the people that they're representing. And obviously the people that are in that image are not like these women that Jenny was just describing, you know, building [00:43:00] infrastructure and creating community in these important kinds of ways.

So I compared that with the one that Jenny also mentioned earlier, too, by, I guess, Augusta Joyce Crocheron, which is, to me, such an interesting response because in its representation of polygamy, which it really does directly address, instead of trying to create, uh, a more positive, uh, what it does is tries to get you to think differently about who Mormon women and polygamist women are. She also published a little booklet that goes with it. And that booklet is pretty straightforward. It mentions, and I think purposefully, because you've had to know if you're reaching a public audience in that time, it mentions that these women are polygamous wives, but then it also talks about the things that they've been able to accomplish. And of course, it frames this system that's so scary to people on the outside as something that is actually liberatory [00:44:00] for the women who are participants within it. To me, it's just such an amazing juxtaposition of two radically different ways of thinking about this world.

It's also, I think, a useful reminder that the truth behind these things is a lot more subtle and a lot more nuanced. And that, you know, whichever side of this you're on, like, not all of the women involved in polygamous marriages in Utah perhaps had the respect for that institution or the positive kinds of outcomes that the women in that print did to be fair. Also, of course, neither was polygamy anything like the ridiculous farce that the illustration in Chic magazine published.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, it seemed to me, reading your three chapters, that polygamy was sort of the thing that a lot of outsiders kept coming back to as a way to, you know, caricature the Latter-day Saints and, and to show them as something different and maybe dangerous to American people.

Jenny, [00:45:00] you also had a really interesting comparison of two quilts related to polygamy, one from inside the Latter-day Saint faith and one from outside. Can you tell us about those?

Jenny Reeder: Absolutely. So, like I said, with that 1870 quilt, it's during this time of severe anti polygamy legislation. And we have another quilt that was made a little bit later by people not of the Latter-day Saint faith in Salt Lake City, and they wanted to send it to, well, they wanted to make a statement most of all about who they were and what they were fighting against. I'm going to have to go back just a little bit. Latter-day Saint women, in the 19th century, lived during this time where the Republican party was really dividing into what they described as the two evils of the time, the twin relics of barbarism. One is plural marriage and the other one is slavery. So this changed a little bit during the Civil War, but then the plural [00:46:00] marriage fight picked up. And so we have this quilt that is made by the anti polygamy association. And it's like a, it's a crazy quilt. It's beautiful actually, but, and it's owned by the Church, which I think is fascinating, but it was a way for them to express the fact that they didn't they didn't approve of that.

They didn't support that there were people in Utah that did not support that. And yet on the other hand, Utah women were the second state or territory given the right to vote. Wyoming women received the franchise before Utah women, but they didn't have an election until after the Utah women had an election. So I think a lot of Republicans figured that if they give women in Utah the right to vote, they would vote off polygamy. But they didn't. They, they became all the more, not all of them, but many of them became all the more [00:47:00] politically involved.

At the same time, polygamy divided the domestic responsibilities. So it allowed women to things that they hadn't been able to do before, like go to medical school, or start a women's newspaper, Lead this grain storage movement or make be involved in the Sarah culture or silk making production. It gave them it opened up their doors to a little bit of more action.

Jenny Champoux: That was really interesting. Ashlee, your chapter also had a little discussion of polygamy with these little paintings of the Utah Territorial Penitentiary from the late 1800s. I just was fascinated by this. Tell us about these and why did these become so popular among Latter-day Saints at this time?

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Yeah, so, polygamy is such a defining issue of the time, and the complexities are so real. I think these [00:48:00] paintings, so there's a series of paintings that were created by an artist named Frank Treseder, and he was a gentleman who had been baptized into the Latter-day Saint faith.

He was a member. He had a lot of encounters with the law. So he ended up in the penitentiary multiple times. And, in 1886, he once again found himself in the penitentiary. This time, what I think is interesting is he was sentenced because He was, um, charged with bribery. He was trying to get some U.S. Marshals to kind of surrender some of their information that could have been potentially incriminating about Latter-day Saints living in polygamy. Which is so interesting, but, so at the time, I mean, we've mentioned this, but I mean, 1882, there's federal legislation against polygamy. So gentlemen, gentlemen, men of the faith begin being [00:49:00] incarcerated at times.

And then by 1887, when we have the Edmunds Tucker Act, the incarcerations of Latter-day Saint men who have plural wives, increases quite a bit. As far as we know, there were probably about 1,300 men that actually went to prison, served their sentences, a prison sentence for not renouncing their commitment to their wives and their children.

More than that were tried, but some, because of extenuating circumstances, were, were not necessarily sent to the penitentiary. But, Treseder is there, again in 1886, it's kind of his last stay in the pen. And while he's there, he, a newspaper article says that they give him space for an art studio.

Apparently he has an interest in art, he's dabbled in it from his youth, so he begins painting these views of the [00:50:00] penitentiary, and the Latter-day Saint men that are there, they were often called cohabs, because they were there for unlawful cohabitation with more than one wife. But, you know, a lot of them, this became a real, I mean, a sacrifice, of course, but it became their way of really, not denying their faith and their covenants.

In that language that they had made, and so it was almost a badge of honor to serve that time. The time could range anywhere from, you know, five to six months to three years, but shorter sentences were, were more common, as I understand it, and a fine, a monetary fine, might have to be paid. And so there was this brotherhood of these, these men that were being incarcerated for they would, it was often called prisoners for conscience.

And these paintings, some men bought them from Frank Treseder, and they would take them home, kind of [00:51:00] documenting that they had been among those that had done time, you know, and not denied the fate. So we know, I mean, these paintings have popped up a few places, but we know, for example, Rudger Clawson, served time in the penitentiary and later became an apostle. He purchased some from Treseder. He writes in his journal, like, I kind of liked them, so I bought some. Daughters of the Utah Pioneers has an example that is just inscribed with the names of, of James C. Watson, that he had also served a prison sentence and had taken one of these home with him.

We also know that, Mariner Merrill, another then apostle, purchased one. And gifted it to his son who served time in the penitentiary for having plural wives.

But again, speaking to the ideal, a lot of the women, when they bore a sacrifice as these men were [00:52:00] away, but to them, it was also a way of, you know, maintaining covenant and being very true and stalwart within their faith.

So it was a tribute to those women also in many cases.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, thank you, Ashlee. It's just a really fascinating history of, in, in the visual artifacts that we have, right? And that they, in the material culture, they were taking home these almost like postcards, these paintings, and I don't know, would they display them in their homes? Do you know, do we have any information on that?

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Likely looking at the scale of them again, most of them were fairly modest, you know, maybe a foot and a half tall at the most, maybe two feet wide. So they're modest in size. So they would be probably most appropriate to be displayed in a home in that kind of setting. You know, passed on from generations of, I know we do know of one painting that's in private collections.

There's probably more right images out there that aren't in the more [00:53:00] public collections yet. So passed down to family.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. And interesting too that, I mean, if you had it hanging in your home, unless you were an insider and knew what it was and what the history there was, what it meant, you wouldn't necessarily know what it was or what, you know, that just, it looks like a nice building. Right? And, and it, maybe you wouldn't know it was a penitentiary and that it had reference to the time that the man of that house had served there for, for polygamy. Yeah, amazing. Thank you for sharing that.

One final theme that I saw here was the way the interiors of temples have been decorated. I mean, today we think about interiors of temples as having pictures of Jesus or scripture stories or peaceful landscapes. Ashlee explained in her chapter that actually the earliest temples had mostly portraits of Church leaders. [00:54:00] And then Jenny Reeder talked a lot about just the incredible hair art that shows up in temples.

Ashlee, can I just go back to you for a second? Just, want to talk about why, why these things, portraits and hair art, showed up in the temple and what kind of theological significance these objects on by virtue of being placed inside a temple.

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Yeah, so, my chapter looks at the Nauvoo temple interior, and that mirrors what we know of the Kirtland temple. So the two earliest temples. And they were largely portraits in, for example, in the Nauvoo Temple Celestial Room. And, I mean, there could be different reasons for that.

And portraiture was so prominent in American painting at the time to show gentility, refinement, to capture likeness. There's lots of motivations behind the popularity of portraiture. But in terms [00:55:00] of the context of it being hung in the celestial room, I mean, the Nauvoo temple is perhaps unique in that at some point during its decoration phase, the latter phase in 1845, 46, you know, Church leadership knew that the paints were going to move west.

And that, I mean, the temple in their minds would stand, you know, indefinitely, but that the body of the saints would be moving West. And so the, the temple was dedicated in, you know, in phases as ordinances were able to be offered. And as the construction was completed. So it could have been that, you know, some of the paintings were borrowed, we know from people and hung there to decorate it like the fine interior of an American parlor.

Right? Very appropriate. Yet at the same time, there is a message there, the idea that the portraits hung were of prominent leadership. And to me, the most interesting painting of that group was [00:56:00] actually a commission, which I think is important, by Brigham Young in 1845. He commissioned almost a, you know, a seven foot tall portrait, it's almost full length, of him standing up.

And it's called Brigham Young Delivering the Law of the Lord. So he's standing in front of a bookcase that has all sorts of books, you know, Josephus and History of Greece, showing his refinement. And this wonderful cloth of honor. So it aligns with a lot of those distinctive portrait elements, but the important thing is he's standing with on a, on a table next to him is a Book of Mormon, a Bible, and his hand is on a book called The Book of the Law of the Lord.

And that was Joseph Smith's record that he began keeping. And, it was known that there were some revelations there. It contained information kind of about the, kind of the organization and leadership of the church of God, the names of those that, donated [00:57:00] to the Nauvoo temple were in that book as well.

So it shows that Brigham Young connected to this very specific book of Joseph Smith's that talked about leadership. It talked about, a message that those who align and devote themselves to this work will be their names will be in the book of the Lord, right? That there is implication of, of salvation connected.

So this portrait was commissioned for and hung in the temple. So I think it's a very pointed message at a time when Joseph Smith has been martyred. Hyrum Smith, his brother also martyred and the leadership is in flux. Brigham Young is the successor and through his role in the church leadership as a senior apostle, but, you know, the Church has never been in this moment before, and there's a lot of uncertainty among different people.

And so that message that Brigham Young [00:58:00] is an inheriting right, that authority from God passed down through Joseph Smith to be a believer, I think is really, really distinctive.

And the portraits of couples, what was notable also that with that were portraits of couples, man and wife together. I think alluding to this idea of, in Latter-day Saint temples, there is considered a crowning ordinance is an eternal marriage where they're a man and a wife are married. And there's the idea that through covenant living, that marriage will be eternal, will not end at death. And so that idea, I think, is playing out on the walls there.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. Thank you, Ashlee. Yeah. I think that's really interesting that they're thinking about authority and succession and displaying it in this really visual way in the most sacred space.

Okay, Jenny, for something very different. Now, we know that hair art [00:59:00] is a popular commemorative approach, not just for Latter-day Saints, but for Americans in the 19th century throughout America. But what, what happens when you put hair art in the temple? How does that affect the meaning of it?

Jenny Reeder: This is such an interesting question, and I'm so glad you asked. I think that we can get a lot of ideas and understanding of their religious views, their ideology by looking at this hair. So, for example, in the Manti hair, Manti Temple hair art, we see this, we have this idea of women giving up some of their hair.

I mean, it obviously wasn't like a big deal for them. They didn't have bald patches in their heads. But, it's interesting that once you cut hair, the color and the texture remains the same. It doesn't change with age, which is so fascinating. And in that way, it's like a snapshot of time. It's a [01:00:00] very specific time, think it's also in, especially in Manti, it's telling this idea, giving this sense of how. One day they will be resurrected and they will be in their prime and in their, their body will be reunited with their souls that, you know, they talk about age and aging, but this hair, this idea of hair, something so permanent. In fact, often they would have hair or quilts or something rather than photographs before photography became so much more accessible. But that was their connection. And I think it's incredible.

Now in the Salt Lake Temple, they're hung up a weeping willow hair piece, hair art. It's now at the Daughters of Utah Pioneers in Salt Lake city. And it's fascinating because they have like a little key of whose hair is whose, but they take care from. They're all from significant leaders. And so we have like [01:01:00] this hierarchy here of the hair, the long hair in the trunk is from women, obviously, because it's longer than the hair of men, but they have preserved hair from Joseph Smith, who never came to Utah, and other leaders that were not there. So it's just interesting to see how that all fits together.

And, my friend, Josh Probert, who also has a chapter in this book, talked about how this is the finest Victorian parlor. And so they want to show the demonstrator or show the, their finest.

Jenny Champoux: That is just I, I mean, the whole idea of hair art feels very foreign to us today, right? But, I think there's, it's really beautiful and, and especially poignant the way that the Latter-day Saint women were using it to visualize community and symbolism about the Zion community that they were trying to build there. [01:02:00] Thank you.

Okay. I want to wrap up every episode by asking each of our guests to share a work of art that is meaningful to, to them. Now, I'm not asking you to share your favorite work of art, because I know that's an impossible question for art historians, right? Or historians. But just something that is meaningful to you, either that relates to our conversation or just, it could be something different too.

Nathan, let's start with you.

Nathan Rees: Yeah, I want to go back to the Brigham Young monument because I think one of the things that really has struck me as I've, I've been doing this research is to realize that these artworks, they're compelling and they, they bring you in and, and, and they tell you a story and really effective, but it's also really important to think about who's being left out from some of these stories. And to me, the Brigham Young monument is maybe the clearest about this because it kind of is. What's the expression? It like says the quiet part out loud. [01:03:00] I, you know, I, I shouldn't be making light of this either, but one of the things that it represents is this native man that's cowering, basically at the feet of Brigham Young, who's up at the top of this monument. And it's a reminder that when these people came, this place wasn't empty. And then if you go around the backside of the monument, among the people who came, three of the people that are listed, they're actually, they're put at, at the end, with a little euphemism. Uh, indicating that they were actually enslaved when they were brought here. And so, to me, it's, it's a really important kind of a reminder that the stories behind these things are so complicated and they're so nuanced. It's important read about this history. I think it's great to celebrate history. But it's also, I think, critical to recognize where these works of art maybe aren't telling us the whole history.

Jenny Champoux: Fantastic. Thanks for that insight. Ashlee?

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Yeah. Um, well, first I'm really glad Nathan shared that because I [01:04:00] do agree. The work of art I actually thought of, this was hard, but I actually thought of one that I think is, well, it's definitely inspired by the 19th century, by this period, but it's actually a contemporary work, that we ended up including in the Work & Wonder exhibition.

And it, it's one that's proved to be really impactful, and it's by the artist Sarah Lynn Lindsay, and she created a handmade linen dress. And this work is an homage to her great great great great grandmother, Sarah Darman Rich. And Sarah Rich was an early convert to the church, you know, went through the persecutions of Missouri, stalwart in the faith.

She ended up marrying Charles C. Rich. Who, in 1849 was named an apostle, to Brigham Young. So they were, you know, prominent and very faithful and lived a [01:05:00] life of sacrifice. And interestingly, she writes an autobiography and really tells about these experiences. I mean, it just is a very engaging and a very, powerful read.

And Sarah Lindsay, the artist, you know, a namesake, really, Sarah and Sarah, she grew up hearing this testimony, these experiences of Sarah Rich, and was very inspired by them, very touched by them. So in this dress, she envisioned Sarah Rich and tried to make it to scale, as if it's, you know, a dress Sarah would have worn.

And it's hung on the wall, and the skirt just flows out in this beautiful circle, almost nine feet wide, with the bodice hanging at the center, and, in circles radiating out from the waist of the dress are lines taken from Sarah Rich's own autobiography, her own words, the same words that [01:06:00] inspired the artist, and generations of posterity and other church members.

They radiate outward and it's just so beautiful. Like the ripples showing how, you know, the experiences of these 19th century Latter-day Saints were so complex and so many of them were undergirded by a faith, a faith that led to sacrifices that changed them, that changed their families and that that's really inspiring to go back to and learn from them and learn the complexities and the hardships and the, The victories and the joys they experience and Sarah's piece is a beautiful metaphor also because it looks like rings on a tree and you look at it from a distance and it's beautiful.

You think of the layers of generations that are impacted by these pioneer era experiences and as we learn more about them, I think it really does enrich us and enlighten us.

Jenny Champoux: Thank you, Ashlee. [01:07:00] Jenny Reeder, can you share yours with us?

Jenny Reeder: Yeah, I'm going to talk briefly about two pieces. One is a gold watch and it's not necessarily a piece of art, but it's a gold watch that Joseph Smith gave to Eliza R. Snow when she was the secretary of the Relief Society and he, one of her responsibilities was to begin and end the meetings on time, but she didn't have a watch. So he gave her this watch and If you look at photographs of Eliza, you'll often see that watch that's like on a chain, either around her neck or stuck in a little pocket on her dress. But the most interesting thing about that watch is that she would often take it with her when she would go visit, especially primary associations and organized primary associations. And she would let them hold the watch. It became a relic. She would let them hold it. And she would say, now you have held a watch that once belonged to Joseph Smith. And these are a generation away from [01:08:00] Joseph that never knew him. And they would grow up and talk about holding this watch. It was, it was an amazing piece.

But the other thing I want to talk about is more of a, vernacular thing, which I really like. I, and again, it's not a fine, fancy piece of art hanging in a somewhere. This is a piece of string, literally that Mary Whitmer, who was the wife of, the wife and mother of the Whitmers in Fayette, New York, and who hosted Joseph and Emma and Oliver Cowdery and Martin Harris and, and a lot of other people. And she made everything, right? She was from Switzerland. She was Pennsylvania Dutch and then come up to live in New York and this piece of string she had created. She had crafted this piece of string because you always needs a string, right? You know, on a farm and it later was used to tie together the [01:09:00] manuscript of the Book of Mormon when Joseph took the manuscript to the Grandin store in Palmyra. And so it's a piece of string. But it shows so much more and that's why I love this idea of women and material culture. It's beautiful.

Jenny Champoux: Oh, thank you. I hadn't heard that before. Thank you for sharing that.

Jenny, Ashlee, Nathan, this was such an eye opening discussion. Thank you.

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Thank you.

Nathan Rees: Appreciate it.

Jenny Reeder: It's fun to meet with other authors and to learn about how their pieces speak with our pieces.

Ashlee Whitaker Evans: Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, I love seeing those connections.

Be sure to join us next time as we continue diving into the history of early Latter-day Saint art. Did you know that in 1890, the Church called several members as art missionaries and sent them to Paris to study the latest styles there and then bring them back to Utah? [01:10:00] Also around the turn of the century, um, quite a few Utah artists were traveling to New York to study at the Art Students League in New York, and then coming back to Utah. So we will learn more about that history next time as we chat with Glen Nelson and Linda Jones Gibbs. We'll see you then.

Thank you for listening to Latter-day Saint Art, a Wayfare Magazine limited series podcast. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. I hope you'll order a copy of the book to read the full essays and see all the gorgeous full color images of the artwork.

You can learn more about the book and other projects at the Center's website at centerforlatterdaysaintarts.org. If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to listen to the other episodes in this series. You can subscribe to Wayfare Magazine at wayfaremagazine.org. [01:11:00] Thanks to our sponsor, Faith Matters, an organization that promotes an expansive view of the Restored Gospel.

And if you'd like to learn more about Latter-day Saint art, check out my other podcast called Behold: Conversations on Book of Mormon Art. You can also learn more at my website, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. With more than 10,000 artworks, it's the largest public digital database of Latter-day Saint art. You can search by scripture reference, topic, artist, country, year, and more. We recently added a new section for art based on Church history, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. The website is bookofmormonartcatalog.org.

That's bookofmormonartcatalog.org. Check it out and see what exciting new art you can find to enrich your study.