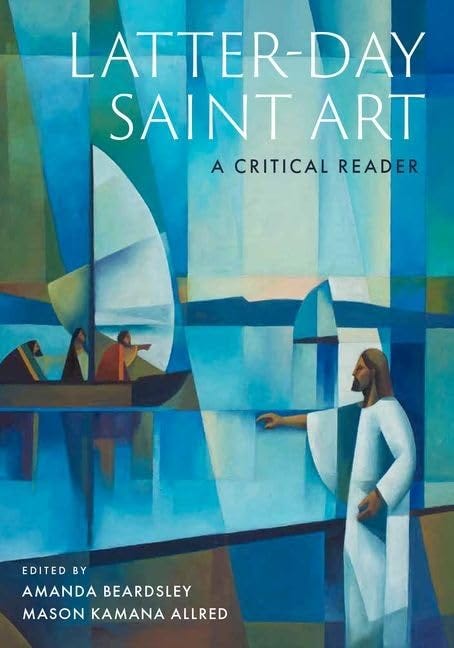

Jenny Champoux: Welcome to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux. In Latter-day Saint Art, I'll guide you through an examination of the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts.

Throughout this series, you'll hear from scholars of various disciplines and perspectives, who each bring their training to bear on a different aspect of Latter-day Saint art history. We'll examine familiar paintings and architecture, as well as lesser-known textiles, films, cartoons, and sculptures. You'll be introduced to new pieces and come away with a greater understanding of the breadth and depth of Latter-day Saint visual arts.

In our first episode, we consider why Latter-day Saint art matters. We'll ask, What distinguishes certain artworks as sacred? And we'll investigate some of the tensions inherent in Latter-day Saint art.

We'll discuss recent trends, including the impact of the Church's International Art Competition, the ways in which some artists are incorporating traditional Christian symbols, and efforts to be more diverse and inclusive in art. Our guests today are Terryl Givens and Laura Paulsen Howe.

Terryl Givens is the Neal A. Maxwell Research Fellow at Brigham Young University. Prior to that appointment, he was the James A. Bostwick Chair of English and a Professor of Literature and Religion at the University of Richmond. He did his graduate work in intellectual history at Cornell and in comparative literature at UNC Chapel Hill.

His work includes the book, People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture, and a two-volume history of Mormon thought, Wrestling the Angel and Feeding the Flock, as well as many other studies of Latter-day Saint scripture, biography, and theology. His chapter in this new book is titled, “A Theology of Mormon Art.”

Laura Paulsen Howe is the art curator over global acquisitions at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City, Utah. She curated The 12th International Art Competition: All Are Alike Unto God, in 2022, and also, With This Covenant in My Heart: The Art and Faith of Minerva Teichert in 2023. Her research has focused on places of display, analyzing how the meaning of a work changes when shown in different environments. Her chapter in the book is titled, “‘Who Did I Leave Out and Should Have Included?’: The History and Influence of the International Art Competitions at the Church History Museum.”

I'm lucky enough to have had the chance to work with both Terryl and Laura, and I can tell you that they are both just delightful and kind people, and truly put their heart and soul into the work they do to analyze and preserve Latter-day Saint art and thought.

So, without further ado, let's dig in.

Terryl and Laura, welcome.

Terryl Givens: Good to be here.

Laura Paulsen Howe: Pleasure to be here.

Jenny Champoux: This is our first episode of the Latter-day Saint art podcast, and we're really starting off with a bang with two of the most esteemed and knowledgeable scholars of Latter-day Saint art. I am so excited to chat with you both today. And thanks to our listeners for joining in. I think you're really going to enjoy this discussion.

Before we dive into your chapters from the book, I want our listeners to get to know you and learn more about the work you do. Laura, could we start with you and have you tell us about the purpose of the Church History Museum and your role as a curator there, and a little bit about how the International Art Competition works?

Laura Paulsen Howe: As an introduction, you're going to have to keep me from talking too much, but I will try to be brief. The Church History Museum is situated in the Church History Department. And the Church History Department's goal is to collect, preserve, and share the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. So the museum is dedicated to collecting, preserving, and sharing both art and artifacts of the Church. So, within that context, art tells a story and art preserves a history. So we are always looking to preserve the story of what it means to be a Latter-day Saint and important trends and things think people are thinking about within our archives. In that context, the Church History Museum started…it was dedicated in 1984. It was initiated a lot because of the efforts of a woman named Florence Jacobson. Among other things, she was sustained in General Conference as the Church curator. The only person who has ever held that calling. And so she hired a number of people and it was really the first time that people who really thought about what art means and what art trends look like was hired to work for the church in a critical way. And so as part of that, the curators who were hired at the end of the late seventies were looking at all of the art that had been commissioned and owned by the church since about 1830.

They were looking and noting that the art largely told the story of the Intermountain West was done by artists in the Intermountain West. Painting people in the Intermountain West. The 1970s were a time where the Church started thinking more internationally in its scope. President Bruce R. McConkie gave an important speech that when you gather to Zion, if you live near Mexico City, you are gathering to the stake of Zion in Mexico City. And, and so as we're thinking about what it means to be a Latter-day Saint and at this point, the majority of members were living outside the Intermountain West, really in preserving the story of what it means to be a member of the Church, we had preserved the story of what was now the minority of its members, And so early efforts in the 1980s, curators at the time, thinking consciously, how do we do better at capturing the story? A more complete story of what it means to be The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. So, the art competition, initially was…The, the Church History Museum, then called the Museum of Church History and Art was approached by Jack and Mary Lois Wheatley, who would later be big donors at BYU Museum of Art and start that effort down there. But they wanted to host a fine arts competition to foster excellent art and the curators pushed for it to be international in scope. It was not called the international art competition at the time. Neither, neither was it called the first at the time. It was just called a fine arts competition. But then later would prove to be important enough and a really great way to help people gather. To have the curators have a curated list of items that they could collect to better tell the story of what it means to be a member of the Church.

Jenny Champoux: That is just fascinating history and how great that you are in that role now to help collect and preserve this history. A really a global history of our members.

Laura Paulsen Howe: You know, it's a great job. There's always things I'm thinking about how to do better. I think it mentioned in my chapter that 20 percent of the art, and this has been consistent since it's begun, in some way comes from people living outside of the United States, I would like that to change.

I would like more representation. I've also thought of how do we decentralize, um, if we're bringing all the best stuff to Salt Lake, then it feels colonial. So how do we get it out? So there's lots of places to go and lots of things we're still thinking about, but it remains the best way for me to find artists inside or outside of the United States, and it remains the best example when I am trying to talk to different people who work for the Church or in Church leadership about style and different ways of bearing testimony of the Savior or telling a story about what it means to be a Latter-day Saint in a, in a broad variety of styles, the art competition is still my best object lesson.

Jenny Champoux: Oh, that's great. Thanks, Laura. And Terryl, you've worked for many years as a scholar and your numerous books are foundational in the field of Mormon studies. I'm sure most of our listeners are familiar with at least some of your books and work. Did you know that your chapter was going to be the first chapter of this new volume?

And if so, how did you hope to ground the reader with this chapter as they moved through the rest of these studies?

Terryl Givens: Yeah, I did not know it was going to be the opening chapter. And, but what I, what I did see as a kind of foundational question to ask is, of course, the question of definition. So, how do we know what we're talking about when we talk about Mormon art and I'll just mention kind of incidentally that when the title is changed from Mormon art to Latter-day Saint art, the object of study changes because Mormon art, of course, is referring to art related to a cultural construct. Latter-day Saint art suggests, it already kind of answers the question I'm asking in a different way that I answer it, right? Because it's already to suggest, well, there's some kind of formal institutional involvement at the heart of, of Mormon art. You know, I taught literature for many years and, you know, there's genres in literature like Catholic literature, Jewish literature, right?

And what Catholic literature means is not the author happens to be Catholic. It means the author is infusing a Catholic sensibility into their writing. And so I, I, assume or operate on the premise that something similar is happening in the case of Mormon art. Mormon art would have to and somehow capture. Reflect a kind of sensibility, kind of orientation with regard to the, the cosmos or, or humankind. And so I try to suggest just one possible way of thinking about the theological dimensions that one sees in Mormon art. So, of course, that bias led me to highlight those works of art that I thought were particular manifestations of different kinds of Latter-day Saint sensibilities.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, it is really a great, I think, sort of broad overview of what are some of the the motivations and themes that we see in Latter-day Saint Art. And your essay focuses on what you identify as two central tensions within Latter-day Saint belief and culture and art.

So, first, you talk about the sacred and the profane. And, or another way, I think you phrased this in the chapter is the transcendent and the immanent. And then the second one is this tension between exile and Eden, or gathering and integration. So, let's first look at this sacred and profane paradigm. I study art history and a lot of traditional Christian art and traditionally Christian religions have made a sharp distinction between thinking about things that are spiritual and things that are material or earthbound.

So how does the Latter-day Saint thinking on this differ from that tradition? And are there ways in which this tension between the sacred and profane can actually be productive or create possibilities for Latter-day Saint art?

Terryl Givens: Well, I think it's created unique, unique challenges. And, you know, the way that Latter-day Saints resolve this duality of the sacred and the profane has tremendously important theological implications. You know, I was in a public discussion with a Jewish intellectual just a week ago, and he was very distressed as he looks back at the Holocaust and asks of Christians, how do you explain the existence of evil and suffering? And he said, and I find their resolutions morally reprehensible. I mean, he was really, you know, somebody looking back at six million executed Jews. And I said, well, you know, Latter-day Saints don't operate within the same parameters and trying to address the problem of good and evil, because we don't believe that God created natural law. We believe that he is a party to natural law. And so right off the bat, that, that, so that's not what we're talking about today, but that's an example of how important our unifying of the supernatural and the natural can be like in the moral or ethical realm. The Catholics were always very big on maintaining this distinction.

That's why in the Catholic tradition, there's always been such an emphasis on the transcendent, on the miraculous, the supernatural. Protestantism reacts against that to some degree, by trying to emphasize more of an immanent God. God is in creation. And then Latter-day Saints collapse it completely, right?

Body is spirit, and spirit is body. And, this has amazed many Christian thinkers. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the poet, once said, right, the heterogeneity of matter and spirit is the ground of all miracle. So, we don't have that heterogeneity. Having said that, right, my favorite example of that, and I'm struck by it almost every time I go to a Stake Conference, is sitting on a basketball court with a basketball hoop overhead watching somebody deliver a sacred sermon. That's the collapse of this distance between the sacred and the profane. The challenge, it seems to me, is that in Latter-day Saint worship, practice, and thought, we can become too familiar with deity. I think there's something really, really amiss when we think of a final judgment happening shortly after our deaths, at which point we will be ushered into celestial glory and participate in Godhood.

I mean, that's just, that's patently absurd. Absurd. And so there has to be a way of accommodating the sacred, the holy feelings of reverence and awe, in a cosmology where there, there is a continuity between the human and the divine. And that's one thing I look for in art. And not a lot of examples come readily to mind. We sometimes move in the opposite direction, as in the painting by Linda Etherington, Sweat of His Brow, which we may talk about later, right, where we get the Garden of Eden reproduced with a man wearing Bermuda shorts. But how can we strive for that sacred while still recognizing that continuity is a hard thing.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, one example you give in your chapter is a sculpture by Trevor Southey of the restoration of the priesthood. It's called The Moment After and I think you see, you see how the sacred and profane are playing out together.

Terryl Givens: This statuary group, The Moment After is, it's my favorite work of sculpture in the Latter-day Saint tradition by Trevor Southey, and of course, it captures that moment after Joseph Smith has received the Melchizedek priesthood at the hands of Peter, James, and John. And the scripture that came to mind when I first saw this was in 1st Nephi, where Nephi, he starts a section by saying, And I, Nephi, return to my tent from speaking with the Lord. And it's, it's, there's like this collision here, right? That is so casual. Yeah, I'm up here on the mountain talking to God.

Now I go and back to my tent and talk to my brothers. So that's another example of this collapse, right? Of sacred distance. And I think this statuary group does it because most, most, I think, sculptors would think of doing this kind of in the heroic mode. And the heroic mode is always timeless, right? You take something out of it, out of the flow of time and captured in this permanent sense that is really, it's an image, but it doesn't, right, try to reach into a temporal continuum and pull out this, this moment. But this does. The fact that we don't, they're not all static. It's like they're getting ready to ascend back into heaven. Joseph is already starting to rise and turn away to go back into his tent. And so what this captures for me is a uniquely Latter-day Saint version of eternity, which is one in which God participates in the temporal realm. He's not a jack in the box that just erupts into our timeline and then removes himself. But there's this complete integration of the divine and the earthly and what we see here is the flowing of time in which the divine participates. I think that's really marvelous.

Jenny Champoux: I loved how you pointed out in both that it's the moment after, and you see this sort of, as they're moving off of Joseph Smith, after having had their hands on him, that there's this sense of linear time and a real materiality of, this was a real thing that happened in a particular moment in time on the earth.

I mean, even the, even the title speaks to that. The Moment After. It’s time-bound.

Terryl Givens: Yeah. Yeah. Typically, if you if you make an angel out of stone, you have to have wings or something, right? But not really material. And here's the sense of transcendent, but no, we don't need wings here. And we've got solid rock, but we're bronze, but that's. That's okay.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. So I want to point out in the book, the caption on this image labels it as being done in 1940. I think it's actually 1980.

Terryl Givens: That definitely is a misprint. Yeah.

Jenny Champoux: This is 1980. Just so our listeners know kind of what time period, um, we're looking at here in, in the history of the art. And I have to say my, my grandparents had, or still have a copy of this sculpture in their house in Salt Lake City. And so I grew up seeing this sculpture. It's in their dining room. And, for me, as a kid, not knowing anything about Trevor Southey, this sculpture always really was intriguing to me because of the three-dimensional aspect of it, the way it encourages you to walk around it and see it from different angles.

And then the, the little feet, right? I remember as a kid, I loved touching the little feet. And so like personally, this is going to be different from most people's experience, but like, I have a very tactile relationship with this sculpture because I've touched it, right. I've, I've touched their little floating feet of the of the heavenly messengers. And I, I think that speaks also to this collapse of sacred and profane, where it is this very sacred spiritual moment, but, the material, the solid metal of the bronze, and the fact that I've held it in my hand, it's also very material and very present right now for me.

Laura, I know this sculpture was in the exhibition that you helped organize, Work & Wonder at the Church History Museum, and this was a retrospective of, Latter-day Saint art. How did you feel like this piece helped tell the story of Latter-day Saint visual culture?

Laura Paulsen Howe: Oh, great. Just to respond a little bit to Terryl's idea, because it relates to this piece so much. One thing I loved about Terryl's chapter that really spoke to me, and I don't know if it spoke to me more, as a Church employee, for whom my job feels a lot like going to work every day, um, within the context that I am working, um, for a church and a religion, right?

But I'm also logging on to my computer and checking my emails. And, or as a Latter-day Saint, I think we understand what that feels like. We are accessing revelation and the ministering of angels, and we do it by getting together and brainstorming what are the needs and how do we fulfill them? And who might, that this idea, the errand of angels is done in a really everyday way, Terryl cites journalist, James Gordon, Gordon Bennett in 1842, maybe a bit derisively, but talking about, how in Nauvoo, Illinois, they are busy all the time establishing factories to make saints and crockery ware, also prophets and white paint, which I just thought was so, That is it, right?

At the same time, we are making something holy and good, but we are the material that is being made that, and we are decidedly material beings. And a lot of that happens in a very logical way and that being kind of foundational to Mormonism. Within Trevor Southey's piece, one other tension that it explores within the context of our exhibition, that Terryl also mentioned earlier in his chapter is the tension between personal and individual revelation, and institutional revelation, and how those fit together and how those sometimes, that there's a relationship between the two, which is interesting to explore. This piece explores that within our Work & Wonder section, which is looking about at that individual and Church, looking at that.

I should note too, I helped organize that exhibition. It was guest curated by the Center for Latter-day Saint arts. Heather Belnap, Ashlee Whitaker Evans and Bronte Hebdon, uh, were the curators for that section. And that piece was so great to lift up and, and tell that idea, looking at what the institution offers by way of ordinances and priesthood, in that moment, but it also holds connotations of authority, but it's also, and I think within the life of Trevor Southey, who is the artist, he was commissioned by the institution to create that piece and he had individual ideas that he came up with. To it with, so it also holds our patronage in the Church is really interesting. And that relationship between those two ideas, we're asking an individual to access revelation, but we have an institution giving feedback. And so, art commissioning by the Church, which I'll note, we are one of very few religions that is actively spending money on art right now and commissioning, but bringing back some of those ideas, there's, there's tensions in that place. So it was such, it is a really foundational piece. It's a really important, it's a really lovely piece. For all the reasons that both of you have mentioned, um, and it carries with it these really important stories and examining, these tensions in Latter-day Saint culture.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, thank you, Laura. Okay, so we're going to shift gears and move on to the, the other tension that Terryl discussed this exile versus Eden dichotomy. Terryl, can you describe for us how Latter-day Saints have seen themselves sometimes quite literally as persecuted outcasts? Or as God's blessed chosen people. And sometimes both at once, how does this work?

Terryl Givens: Yeah. And this is one of the most, like, glaring tensions that pervades Latter-day Saint life and culture. I mean, even to the, I give the example, are we Christians? Well, when Presbyterians tell us you're not Christian, we're so wounded. We're so hurt because we want to be part of the community. But then we say, but you're part of an apostasy and we're the restoration. So, theologically, doctrinally, we haven't resolved that. I think another way we haven't resolved is, is we still use the language of the fall, to indicate that we are all, you know, we're all exiles here. We've inherited that word from, from the Protestant and Catholic traditions alike. It's not a biblical expression, the fall, and Mormon theology thoroughly repudiates that idea, right?

No, this isn't a fall. This is an ascent. This is part of a planned ascent to, to Godhood. And that's why I like, uh, the painting by Etherington, Sweat of His Brow, where we have a picture of this family. And, and the title tells us, you know, that this is a rendering of the story of Eden, right? Sweat of his brow. But what we see is this family that it looks like, oh, they're, they're in the middle of a family home evening activity. I mean, there's no sense of the tragic. There's no sense of exile here. We're reminded in this family grouping that, oh, this was the purpose of it all. In fact, one of the most remarkable moments in Joseph Smith's translation history is when he's retranslating the story of the fall. And we don't get this in our 1981 version of the scriptures, but what he wrote in his manuscript was. In chapter six of Moses, human beings were born into the world by the fall. So, we thought, no, we're, this is a catastrophe. Joseph flips it 180 degrees by saying, no, no, no. The whole purpose of mortality is advanced by the, the, the fall. And I think she, she captures that paradox. But my favorite example of that paradox is the, the painting, um, by Weggeland, oops, help me with his first name.

Laura Paulsen Howe: Dan,

Terryl Givens: Dan Weggeland. And he paints this, this painting called Gypsy Camp, and I mean, I'm looking at a copy right here. You've got gypsy tents. You've got a gypsy with a tambourine.

You have an old woman smoking a pipe. You've got a palm reader, but for much of the history of this painting, it was displayed. And when I found it in the storage facility, it was at the University of Utah. I think the title on it was Campsite along the Mormon trail, and I find that just kind of hysterically funny because we're looking at that and we are calling it campsite along the Mormon trail when it's clearly a bunch of gypsies. And I think the reason it gets misidentified is because what we see looking at it are a group of itinerant, right? They're travelers. There's a fence that separates the encampment from the tilled fields, from civilization, from, from society. Um, there are even some parasoled, well dressed, aristocratic women walking through the gypsy camp. And so all we see is ourselves as the marginalized, the exiled, um, even when that isn't even the subject of the painting. So we have this propensity to claim exile as a badge of our chosenness, at the same time we are at times wounded when that label is attached to us.

Laura Paulsen Howe: I can't tell you how nervous Terryl's whole analysis, as a curator who names paintings sometimes go, what mistake am I making right now that down the road scholars are going to find all sorts of meaning in.

Jenny Champoux: That is just such a fascinating example. And, and especially because Dan Weggeland was one of our earliest artists working in 19th century Utah. And we see this with C. C. A. Christensen's work also that right from the very beginning, these, uh, these themes of exile and Eden of, of being chosen, but also being outcast are part of this Latter-day Saint thinking.

And it shows up in the art right away. And, and still today in like in the, in the piece by Linda that you mentioned, it's still there.

Terryl Givens: Yeah. Yeah. It reminds you of the line in Fiddler on the Roof, right? The Jewish father. Yeah, “I know we're chosen, but couldn't you just choose someone else once in a while?”

Jenny Champoux: Yeah. So Terryl, I was also interested at the end of your essay, you talk a little bit about some recent trends where you see Latter-day Saint artists incorporating Christian or traditional Christian symbols, visual symbols. So you see this in the way some artists are turning to traditional mediums like stained glass, the way they're no longer shying away from crucifixion imagery, or the way they're appropriating famous Catholic art forms. Like you mentioned the baptistry doors by Ghiberti in Florence.

Terryl Givens: Exactly. And those, we get a Mormon version of that in Jacob Dobson's Articles of Faith doorway, which seems to me so consciously modeled after the Ghiberti doors. So. Yeah, there are a number of artists who are doing this, it seems to be very self consciously and very deliberately, and I actually like it.

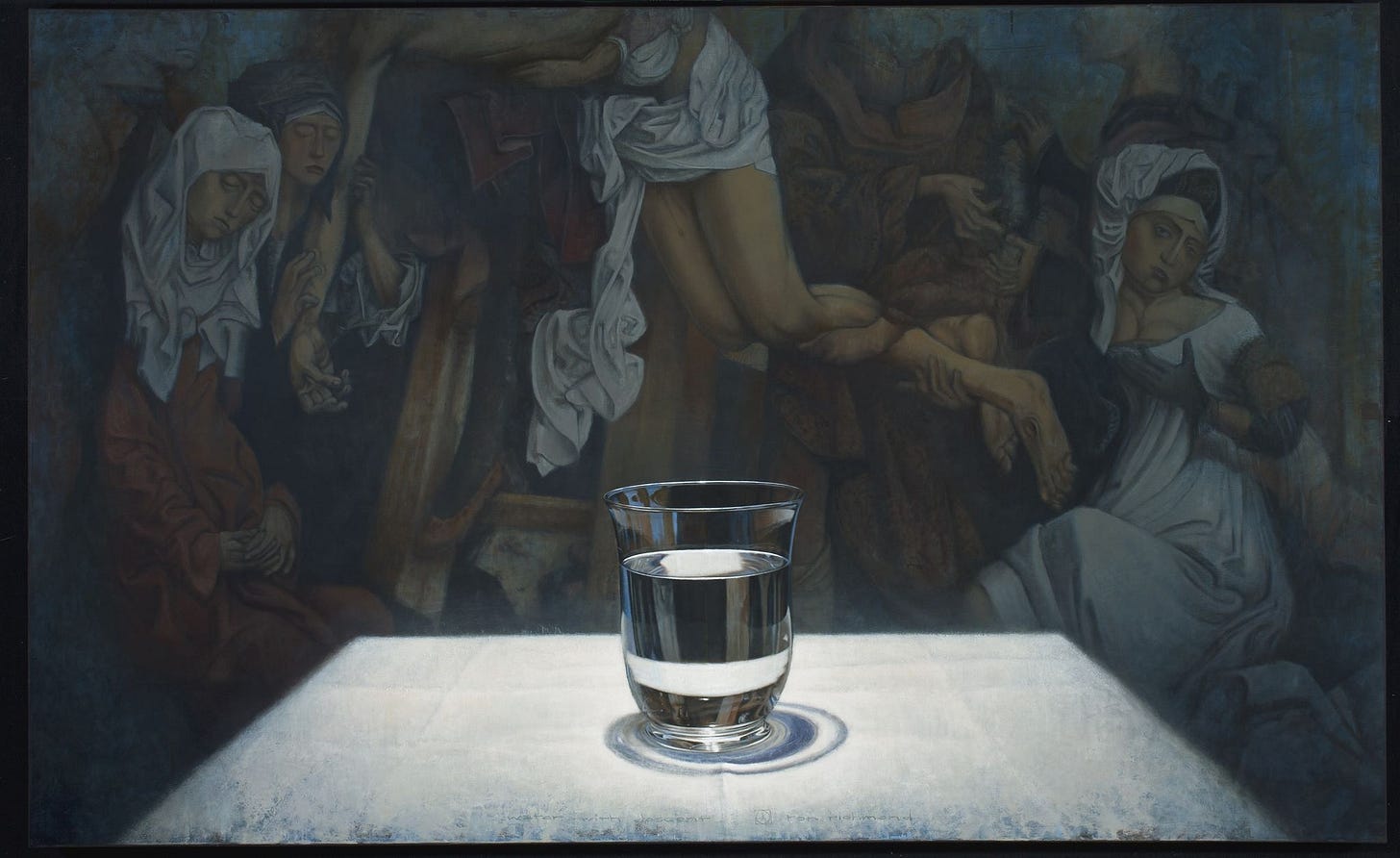

I mean, I, I think, you know, I'm writing a history of Christianity right now, not to digress too much, but, Oxford was very interested in it when I called it a Latter-day Saint version of Christian history. Subsequently, I decided, no, no, no, I want to write this as a Christian. And so they, they're not so sure. But I feel like we need to do more to own our Christian past, our Christian roots. We're not completely cut off, from, uh, you know, we didn't arise in a vacuum. So you have Ron Richmond, this beautiful, beautiful painting, Water with Descent, in which in the back, there's kind of an old master painting of the descent from the cross, but there on the table in front of us is a glass of water. Which I take to represent a sacramental, and so you've got this vivid contrast between high church ritual incense, low church, right, Mormon sacramentalism. Even as you're integrating into one panel the images of, of great Christian art, Jorge Cocco does the same thing, right, by just his use of familiar Christian themes.

You mentioned the stained glass versions of the first vision, which to my mind is a really, I mean, you have to think about it. That's kind of, again, a jarring juxtaposition. A vision where Christian creeds are referred to as an abomination, but it's represented in an old Christian art form. So I, I actually like to see all of this integration taking place.

I think it's, I think it's healthy. I think it suggests we've come to a place where we no longer have to identify ourselves against the other that can find common ground.

Jenny Champoux: Oh, I like that a lot. I, I've noticed this too in some recent work by Rose Datoc Dall and J. Kirk Richards, where they're even framing their art in a way that is reminiscent of these medieval altarpieces, or having a curved top edge of the canvas, which again reminds, takes us back to some of those, triptychs and altarpieces in the old Catholic churches.

Laura, what, what do you see happening from your perspective at the museum? And what do you think are some of the factors contributing to this shift?

Laura Paulsen Howe: That's a good question. First I want to qualify shift a little bit.

Jenny Champoux: Oh, okay.

Laura Paulsen Howe: Certainly not to contradict anything that has been said, but art is never out of a vacuum, it's always going to use the language of the artist of the culture that it's speaking to create something. So when we go back to Dan Weggeland, he brings with him some training at the Royal Danish Academy, um, a tradition of genre paintings in Scandinavian art. And so that's the language that he knows, and so that's what he's going to use. To speak with, I think Tom Holdman's First Vision is fabulous. It's referring back to an older, our most, well, we have a reference of C. C. A. Christiansen doing a First Vision that's not extant, but the first, First Vision that is extant, uh, is in the Holy of Holies in the Salt Lake Temple that Tiffany creates of that first vision.

Jenny Champoux: I just wanted to point out to our listeners that that first one was a stained glass and the recent Tom Holdman one that you mentioned, those are both stained glass.

Laura Paulsen Howe: A stained glass. And so I think that is within the American culture at what, where at the moment Zion was gathering to Zion was actually the early 19th century, quite diverse. And you have people from lots of places in the world, but once we get to Zion, we're situated in the United States and the access they had art to stained glass was one of their options. And so I think that sacred and profane idea that Terryl's already explained, the profane part of that is practical. How do we beautify Zion? How do we illustrate Zion? It's going to be what languages, art languages, do they speak and what art languages do we have access to? So I think that's always going to be part of it. If we have artists, so I think we were always drawing from traditions, whether that be Christian tradition or whether that be in the 50s and 60s. We had all these out of work illustrators in the United States. And so we put them to work. So I think the practical connotations of where the Church was growing, um, the, the context of that and the art they had access to changed.

What I think we're seeing a shift a little bit is a greater acknowledgement that the Church does not exist solely in the Intermountain West. Um, and we have lots of artists all over the place speaking many, many different visual languages. We have a greater awareness among artists of Christian medieval traditions and altarpieces and Paige Crossland Anderson's created this fantastic piece that draws on her visual heritage of quilts, but also draws on an altarpiece, the Altar of Ghent, by Van Eyck.

And so synthesizing is, I think the artists have access to more visual languages. And the audience is better adept at reading these languages or moving towards greater acceptance, if that makes sense. Ron Richmond for decades did these beautiful, essentially Christ sacrifice on the altar, which we partake of in that sacrament of putting that water front and center, and he did that for a long time, but his audience was missing the point. And so he thought, if I have Christ descending from a cross, maybe they'll get it, right? Because he's trying to, uh, speak to a language. It's the context of the art that is in that case was fueling him to, to, to pull in and unify those two. Those two together. So I do think if there's a shift happening, I think that I would like us to be much more able to be multilingual in our art acceptance and our art creation. But I think we are understanding as a people that maybe that would be a good thing, maybe not always for art, but at least, in who we are and acceptance of the church being preached to every nation, kindred, tongue, and people, and not looking to the inner mountain West as the sole source of culture creation.

Jenny Champoux: Laura, thank you. I really appreciate that perspective of how people outside of Utah might, have a different way of approaching art or different, different language of art, different symbolism that they're using, and that they can understand. I noticed Terryl pointed out in his essay that these tensions he talks about largely stem from the American Latter-day Saint experience. So do you, do you see with your work with global art, do you see those same tensions in the International Art Competition showing up or, or what are some of the differences you see between American art or art coming from members globally? And I'd love it if you want to give us a few examples, because I loved all of the gorgeous art you talked about in your chapter.

Laura Paulsen Howe: It's really fun to be able to talk about my very favorite pieces. So that's fantastic. One thing that Terryl talked about that I thought was really fascinating, is, uh, the idea between providing, I can't remember Terryl how you said it, so please fill in if I'm mischaracterizing you, but art that offers answers and illustrative because it seems so real and tangible in a profane world. And at least the institution has felt more uncomfortable with art. That is a little more symbolic and relates and provides kind of this space. Does that feel like an accurate summation?

Terryl Givens: yeah, I think, I think my dichotomy was maybe more critical and stark, but there's, there's, you know, there's a difference between illustration and art, you know, and art seems to be that what you see in our chapels and you see in our meeting houses is illustration. Um, right. It's meant to simply. reflect a historical moment or episode in the life of Jesus or, or, or something. And so you can't get art that is richly evocative.

Laura Paulsen Howe: Sure. Yeah, I think that's fair. I'd have illustration as just one of the genres of art, just a specific training. I think some of that dichotomy exists, uh, within art that descends from, uh, from a Western paradigm art that descends from, um, the Italian Renaissance assumes a naturalism, or kind of a witness of this is how things happened because it looks like the natural world. And so what we see in Western art is kind of a tension between those two things, that art that says this is what happened or art that allows for more interpretation. That is not a dichotomy that's as important in art forms that don't descend from the Italian Renaissance. There's not an assumption up front that this is what happened.

African wood carving is testifying to what it actually looked like when Christ fed the 5, 000. Or this painted screen from Japan is not a witness of how things looked as a replication. And so the art form outside of a Western culture automatically assumes one that it's interpretation and assumes that someone is pondering on the ideas of Latter-day Saint theology and not a witness to how things occurred. And so there's a lot, I think, to be gained by, being familiar with art languages that don't look just like a photograph. The desire for things to look like a photograph, is a really Western desire, that and that desire for skill that say, oh, I couldn't tell the difference. But the problems that happen as a result to that is artists are not photographers and even photography is creating a perspective of a scene anyways. So there is always going to be individual interpretation, no matter how accurate it looks or how much church feedback was given. It's never going to be a witness of this is how it happened. Um, and the church constantly is facing people who feel that because the Church put it out as an image, that must have been how it happened, if that makes sense. Um, so that room, uh, for interpretation and pondering on what it means, um, it is interesting within that context.

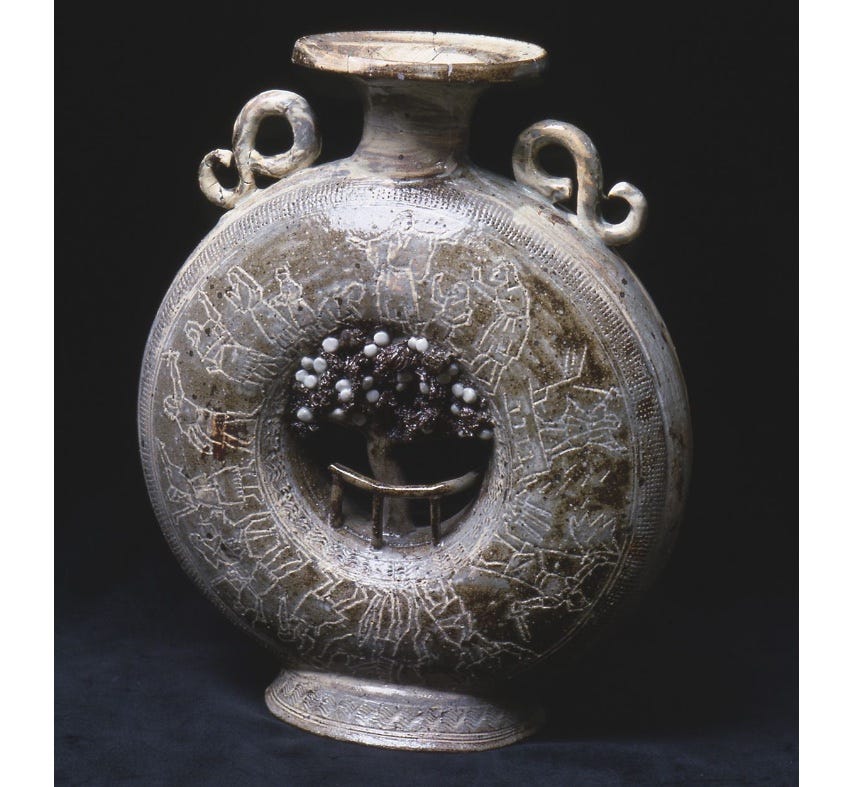

Some of my very favorite works that I mentioned, uh, in, in the exhibition, or in the chapter, Aoba Taiichi is one of my very, very favorite pieces. Become Familiar with the Scriptures. As a matter of fact, this artist is a general authority. And he was just released as temple president for the Fukuoka Japan Temple. But he's working within an art language of ceramics. Where within Japanese culture, ceramics are a very important part. The tea ceremony has driven culture for at least a millennium. And he creates this piece using Japanese art forms, using, um, traditional, uh, pigments that he creates from natural elements. He doesn't use a modern kiln. He tends his fires, uh, for a long period, staying up for days and nights to tend to the ceramics. So using kind of this old art language, um, he creates a meditation on the scriptures. And so in the circle around the piece, he has images from, Book of Mormon stories. And how much they reflect Arnold Friberg paintings is, is something else for exploration later, but the story of Lehi and his family, leaving Jerusalem for the New World, um, or at least the new world as, as it is, as was thought of for a long time. In, in order to express that and within that he's got a central tree of life, a Book of Mormon scene, um, approaching that love of God. So it becomes a meditative piece on the love of God and how he's accessed it through the scriptures. But the language of it that he's communicating is very Japanese and communicates well to a Japanese audience.

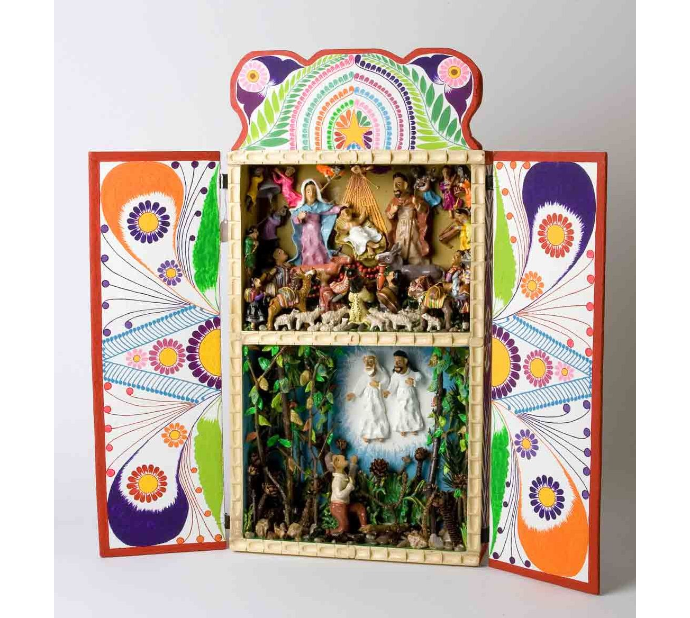

Another piece I like very much is by Jeronimo Lozano called Our Heritage of Faith. He similarly is using a traditional art form, a Peruvian retablo. He is Peruvian and in this traditional art form, you have two shelves within a mobile altarpiece with doors that open and shut. Uh, and the top shelf was often reserved for Nativities, things of the spirit, while the bottom shelf is referred to scenes of everyday life. And so what Jeronimo does is in a gold background scene, paints the nativity, uh, the Christ child, Mary, Joseph, all the sheep and goats and llamas, because this is a Peruvian scene coming with bell ringers and Peruvian instruments. But the bottom where it was reserved for scenes of everyday life, we have a scene of Joseph walking into the sacred grove, kneeling down and seeing God the Father and Jesus Christ. So he's reifying that sacred and profane, that the sacred scene and the, uh, And the everyday life become one in the same, whereas up in the sacred everyday Peruvian life affects the nativity. And down below we see deity coming into the real world. Christ has white hair, God the Father has dark hair. So even the physical material differences and how he portrays them emphasizes that this is, you know, something that as Joseph really happened, right?

He's emphasizing, this is an everyday thing that something holy and sacred happened. Neither of these pieces is their assumption that you would not look at these. Any audience, I think even globally would not look at these pieces and based on their style, assume this is what really happened. Because they're using an art language that allows for these individuals to express their own personal faith in the language that they, that they speak, the art language that they speak.

Jenny Champoux: That is so fascinating. Thanks for walking us through those. They're, they're both beautiful pieces of art. You made two points in, in your chapter that I thought were really interesting in terms of just thinking about non Western perspectives. So first, you mentioned that by the time they did the second International Art Competition, they realized, the organizers realized they were going to have to open this up to different types of media, right?

So, the first one was more painting, maybe sculpture, or can you tell us more about that?

Laura Paulsen Howe: This is my favorite story. And, this is my favorite soapbox to jump on. So I would love to jump on it for you. Fine arts competition. That first one was brought as a fine arts competition to introduce fine arts around the world. And so they said, what are the media? Well, first, the, to advertise that international art competition, they, they worked with the magazines for the church to advertise.

That was the international form of communication that was available in 1986. And so it had to be individually translated by the translators working for the magazines. So the call for a fine arts competition goes out and in Tonga, the translator in Tonga who is Tongan, calls up the curator, Richard Oman at the time and says, I'm having a hard time translating this call for art. It says fine arts competition. What does that mean? There is no word in Tongan for fine arts and the curator, Richard Oman, is forced to think about this Western distinction, a line that we have drawn between fine arts and folk arts in a way that seems to fall apart and doesn't make sense when you're thinking globally. Um, And so he says, okay, well, fine art, sometimes we consider training, but I guess folk art has a lot of training as well. And so when he comes down to it, he's like, media, it's media. Some media are considered fine arts and other media are not considered fine arts. And the media, which is what was expected, accepted was oil, acrylics, watercolor, um, charcoal, photography. And so the translator in Tonga says. Great. What about finely woven baskets? Are finely woven baskets accepted in your fine arts competition? And he says, no, finely woven baskets are not accepted in our fine arts competition. He says, okay, what about tapa cloths? Are tapa cloths accepted in your fine arts competition? He said, no, tapa cloths are not accepted in our fine arts competition. He's like, okay, I guess Tonga's not invited to this one.

And so that thought, that line we draw between what is art and what is not art falls apart globally, and they realize that if they wanted an international art competition, media had to be much broader. And so, at that point, we accept near everything, and that was true from the second one that we had to accept tapa cloth if we wanted Tonga to participate. We had to accept Chinese calligraphy ink, if we wanted that to come. If we wanted it from Malawi, banana fiber had to be part of, of the fine arts competition. Because all of these different languages that have been spoken globally for a very long time, often much longer than oil, that was invented, you know, relatively recently, as far as art history goes, but certainly extended beyond, or happened before the Italian Renaissance, that we needed to be more broad in our spoke scope, both of what art is and, and how it's expressed.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, that and, and it creates such a more rich and beautiful picture when we have all of those different forms gathered together. So I think that's, that's a great example of how maybe some Church leaders are trying to be more inclusive and, and diverse in our collection of art. And including our global membership.

And then I also just wanted to ask, are there other initiatives being undertaken at the Church History Museum or in other departments to be more inclusive and diverse in the visual arts?

Laura Paulsen Howe: The question that everyone who works for the Church is asked is, how does this affect our global membership? It is kind of the base question. In fact, I'd say you can see efforts outside art a lot more clearly than within art, but that's because of the sacred and profane. And there's more work to do, which is great. I think maybe one example, I should say too, I am not behind these projects, so this is me as an observer, but not as a spokesman for the Church, but I think the, For the Strength of Youth pamphlet, that historically was a whole lot more prescriptive in ways that made sense, perhaps in the Intermountain West that did not make sense in, um, Ghana. I think that's driven by thinking about what this means in a global church. I think recent changes to garments has much more to do with how does this make sense? And can we maintain being sacred in a place that is not the Intermountain West? Back to Western Africa, actually, is where I'd go for that.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah.

Laura Paulsen Howe: I think a lot of things trying to make sure that we're thinking of how this is reading globally drives most of the changes that you're seeing is how do we be more thoughtful of all of God's children and thinking about how things land. I think, uh, is, is very important within the Church History Department. This one I can speak better to because it's, it's from the department in which I work. But for example, it's historically, if you wanted to tell stories about Africa, you had to come live in Salt Lake to make that happen. We're trying very hard to decentralize and make sure it's not just storytellers historians who trained at Utah universities and went out and came back to Utah to tell a global story. But now every area of the Church has an employee who lives in that area, who is from that area, telling those stories of the Church and they're serving as the Church. Now, they're one person in each area. We still have a lot more in Salt Lake. So, so clearly, there's more ways to think through the profane of how do we make sacred things happening. And that's, that becomes a job, but efforts to decentralize, um, to allow areas to create their own products. Which is a big thing going on around Church campus, is a huge movement and is, is the major thrust of Church employment at the moment.

Jenny Champoux: Oh, great. Those are some really exciting developments. Terryl, from your perspective in the academy, do you see any efforts to be more inclusive of our global membership, either from scholars or artists or Church leaders?

Terryl Givens: Oh, yeah, there's no question that there have been for some time, uh, initiatives emanating especially from the Church History Department that make it, have been making a very concerted effort to do global Mormon studies, to do women's studies, you know, the, the women's, I can't remember if you just mentioned the women's archive, the archive of, of women, yeah, the oral stories. So I, yeah, I think, I think in that regard, a lot is happening. I don't know that you can, there's such a thing as programmatic inclusivity. So, I think, to some extent, what I would like to see, and I think is happening, is more individual initiatives as we just acquire a greater sensitivity to the multiplicity of Mormonisms, not just geographically. Ideologically, and just, you know, there's just a lot more room for a greater variety of Latter-day Saint voices to be heard and to be acknowledged in our own past and present makeup.

Jenny Champoux: Yeah, thank you. So at the end of every episode here, I want to ask each of our guests to share a Latter-day Saint artwork that is particularly meaningful to them. And it could be from your chapter or our discussion, or it could be something completely different. So could you each tell us just quickly, maybe give a brief description of the artwork and, and why, why you chose it.

Laura, let's start with you.

Laura Paulsen Howe: Jenny, you are an art historian, and you know, the worst question in the world is what is your favorite art.

Jenny Champoux: I know. I know. I know.

Laura Paulsen Howe: One of my favorite pieces that I have found personal connection to and have shared quite a lot and have found meaningful is Fitting Fragments by Paige Crosland Anderson.

It is in my book, in the chapter that I wrote and has come through the International Art Competitions. Paige, uh, her works look like quilts. They're made in oil and her process is to create layers and layers of paint and then mask various areas off. And then she sands them down. What I like about this piece, she created it for, uh, the, 11th International Art Competition, which the theme was meditations on belief. And so she took the opportunity to meditate on what it means to believe. And so in her piece, she has some squares that are solid. They are pure, saturated red. And they sit right next to other squares where you see, uh, a little bit more murky blues and yellows that are interacting with each other. And the way Paige said it is there are things that I feel solid in, that I know, uh, in a way I know my family loves me. I, I believe in God. I feel really solid in some areas and other places I'm still kind of working with that I'm, I'm pushing. She uses an example of if God created the world, that means he created lions and tornadoes. Is God wild? What does this say about God? And things that I don't have answers for, and in some ways, uh, the world and the Church doesn't have answers for as we are learning and progressing. But there's a lot of beauty in those things sitting side by side with each other. There's a lot of beauty in, um, feeling strongly about something.

And the picture of that belief makes up discipleship and makes up a learned and lived experience. Um, so I, that's one of my favorite pieces.

Jenny Champoux: That's a beautiful piece. And I like that you picked something that is a little more conceptual and abstract. And, as Terryl was saying is sort of different from our tradition of the more illustrative, like trying to illustrate or, or teach something through the, I mean, it is teaching, but not in a more didactic sort of

Laura Paulsen Howe: Sure, sure. A different, it's a different art language, right?

Jenny Champoux: Right. That's exactly right.

Laura Paulsen Howe: Something different. So, um, a piece that I, um, would, as people are pondering about their belief and what it means, I find it a deeply comforting piece. So, so one that I've shared often.

Jenny Champoux: Thank you. Yeah, I love that. All right, Terryl, can you tell us about a piece that speaks to you?

Terryl Givens: Got a couple of favorite artists. I love Walter Rane. I love an artist that most Latter-day Saints probably haven't heard of, Kameron Coleman. We have two of his really large originals hanging in our own home. Uh, my wife's favorite is certainly The Comforter, which is a rendering of the feminine divine. Quite beautiful and really, really evocative of that sense of the sacred, the holy that I was talking about. But my favorite is, is probably the, the, um, Descent from the Cross by our friend Brian Kershisnick. And what I like particularly about his rendering of The Descent is, you know, um, if you've ever watched an old movie, let's say you're watching one of these Jane Austen movies and you look and you see the library of the father represented, it's going to be these old, old antique books. No, they wouldn't have been old and antique then. We always project, right, the past through a lens that makes it feel. ancient. And Brian doesn't do that in The Descent from the Cross. I feel that what he has succeeded in doing emotionally is to capture the, the, uh, the tragic experience of the crucifixion on the part of those who didn't know how it was going to turn out. And he does this through color. We have, you know, everybody's dressed in dark. You have the bright white illuminated angels. The body of Christ is a ghastly, cadaverous gray. Uh, it's, it's, there's no hint there that this body is going to come to life again. The faces of the angels are concerned and alarmed. Everyone else is consumed with grief. And I think it, It allows us to participate in a fuller experience of that sacrifice, if we can, to a little degree, vicariously participate with the contemporaries, uh, who lived through that.

Jenny Champoux: Hmm. That is a, that's a really interesting perspective. I like that the way it makes it maybe more immediate to us as the viewer. Yeah. Thank you for sharing that.

Well, Terryl and Laura, thank you both so much for talking with us today. I think this was a perfect introduction to thinking more deeply about Latter-day Saint visual art.

Terryl Givens: Hope so.

Laura Paulsen Howe: Thank you. Thanks for the opportunity.

Jenny Champoux: And for our listeners out there, I hope you'll join us on the next episode where we'll talk with Jenny Reeder, Ashlee Whitaker, and Nathan Rees about how 19th century Latter-day Saints used art to visualize their identity and to create community. We'll cover everything from the earliest paintings of Church history, to monumental sculptures at the World's Fair, to Utah women's quilts, and even hair art. You won't want to miss it.

Thank you for listening to Latter-day Saint Art, a Wayfare Magazine limited series podcast. Each guest is a contributor to the new book, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader from Oxford University Press and the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts. I hope you'll order a copy of the book to read the full essays and see all the gorgeous full-color images of the artwork.

You can learn more about the book and other projects at the Center's website at centerforlatterdaysaintarts.org. If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to listen to the other episodes in this series. You can subscribe to Wayfare Magazine at wayfaremagazine.org. Thanks to our sponsor, Faith Matters, an organization that promotes an expansive view of the restored gospel.

And if you'd like to learn more about Latter-day Saint art, check out my other podcast called Behold: Conversations on Book of Mormon Art. You can also learn more at my website, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. With more than 10,000 artworks, it's the largest public digital database of Latter-day Saint art. You can search by scripture reference, topic, artist, country, year, and more. We recently added a new section for art based on Church history, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. The website is bookofmormonartcatalog.org. That's bookofmormonartcatalog.org. Check it out and see what exciting new art you can find to enrich your study.