Before the gospel of Jesus there was the gospel of Caesar Augustus.

“The most divine Caesar,” proclaims an official 9 BCE Roman inscription, “who being sent to us and our descendants as Savior, has put an end to war and has set all things in order . . . the birthday of the God Augustus has been for the whole world the beginning of good news.”

It was in the wake of this proclamation of good news—the gospel of Augustus—that John the Baptist emerged from the wilderness, wearing camel’s hair, eating grasshoppers, and speaking of one who would baptize the people “in the Holy Spirit.”

Jesus came to John to be baptized by him and, for a time, to live as he lived. For forty days and nights after his baptism, Jesus prayed and fasted in the wilderness “with the wild beasts,” overcoming temptation. Then he emerged, transformed and on fire with good news.

“Jesus came to Galilee,” reads Mark 1:14–15 (ESV), “preaching the gospel of the kingdom of God, and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand. Repent, and believe in the gospel.’” These are the first words out of Jesus’s mouth in the earliest gospel account we have access to today. Straight out of the wilderness, before anything else, Jesus preaches the good news of the kingdom of God — a kingdom that, contrasted with the kingdom of Augustus,1 blesses the meek, the merciful, the hungry, the poor, and the powerless.

How do we experience the good news of the kingdom of God?

As Jesus says, we must repent.

And yet repent is a word with a contested history. Around five hundred years ago, a Catholic priest named Desiderius Erasmus claimed that the common Latin translation of the word had incorrectly been confined to mean “performing external acts of penance.” Instead, Erasmus argued, the Greek verb “to repent” (metanoeó) is more about “a change of mind.”

Contemporary dictionaries tend to agree with Erasmus and add that the verb can also mean “to turn around” or “to adopt another view.”2 Taken this way, metanoeó is not primarily about external acts. Instead, it’s primarily about changing your mind as a result of how you see.3

To enter the kingdom of God, in other words, we must at the very least see beyond the surface. How else can we see that the poor and the meek are blessed? On the surface (in the kingdom of men) the poor and the meek have failed, and small things like sparrows, lilies, a pinch of yeast, and mustard seeds are essentially worthless. But in the kingdom of God, beyond the surface, these small things have tremendous worth and potential.

To change your mind—to repent—is to see this worth and potential. It is to see that everyone is a child of God. It’s to see a world where each person is deserving of forgiveness, a world where even our enemies are worthy of love, a world where we have the capacity to extend grace to all people just as God lovingly sends rain and sun on all people. This is the good news of the kingdom, a kingdom where, unlike the gospel of Augustus, everyone is a brother and a sister, independent of worldly status.

Of course, entering this kingdom is easier said than done. If I’m honest, part of me resists the idea of inherent worth—mine and yours. This part of me believes that my worth is based entirely on what I do and what other people think of me. As embarrassing as it is to admit, this part of me craves praise. It even believes that without praise, I’m worthless. This part of me, to put it starkly, lives firmly in the kingdom of men, the kingdom of status. It believes the gospel of Augustus.

The problem with this part of me is that no amount of praise can possibly satiate the craving it feels. I could receive dozens of kind comments from strangers and loved ones, and I would momentarily feel some pleasure and safety. But within a day (or two or three) that feeling would fade, and I would be left craving more. “Please, like me!” this part of me says. “Please admire me! I don’t want to die unknown!”

This part of me fixates on surface credentials—money, looks, degrees, and so on. It plays the comparison game, feeling good when I perceive I’m “better than” and feeling bad when I perceive I’m not. No wonder Jesus urged his followers to not judge each other: It’s only by avoiding judgment that we can experience the good news and enter the kingdom.

Crucially, this message extends not only outwardly but inwardly as well. As Jesus says in the Gospel According to Thomas, “If those who lead you say to you: See, the kingdom is in heaven, then the birds of the heaven will go before you; if they say to you: It is in the sea, then the fish will go before you. But the kingdom is within you, and it is outside of you.”

On both fronts—the inner and the outer—this is good news. Internally, it’s good news because, by seeing differently, we acknowledge and transform the “enemy” parts of ourselves, the parts that we can’t hate out of existence, the parts we can only integrate through honesty, forgiveness, and love. Externally, it’s good news because we join a community of sisters and brothers who work in harmony to love all people, even those we initially perceive as enemies. In the kingdom of God, no one is alone.

It’s not difficult to imagine that Jesus experienced this way of seeing during his time in the wilderness. Something about fasting and praying in solitude sparked a fire in him that never went out, even as his own family told him he was “out of his mind” (Mark 3:21) for what he preached.

Viewed this way, to restore the gospel of Jesus is, perhaps at a baseline, to likewise live on fire. It’s to see an ever-flowing abundance of love, inside and out. This insight is a pearl of great price, a treasure in a field. It is worth living for, in sacred communion with others who are also on fire, fully alive.

Jon Ogden is the cofounder of Uplift Kids, which helps families explore wisdom and timeless values together. To subscribe to his column, first subscribe to Wayfare, then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for “One Step Enough.”

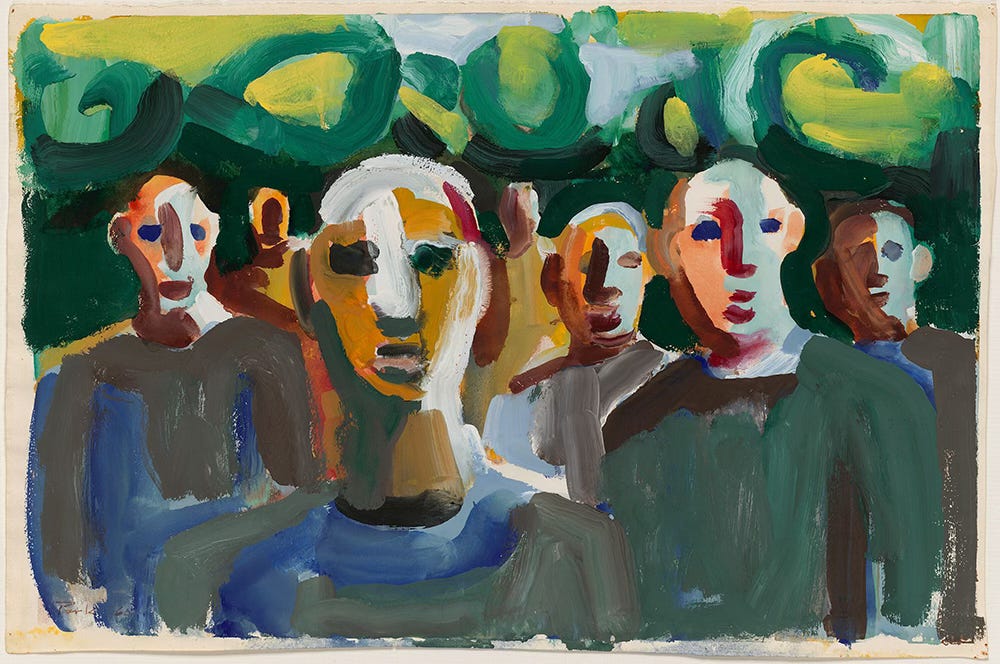

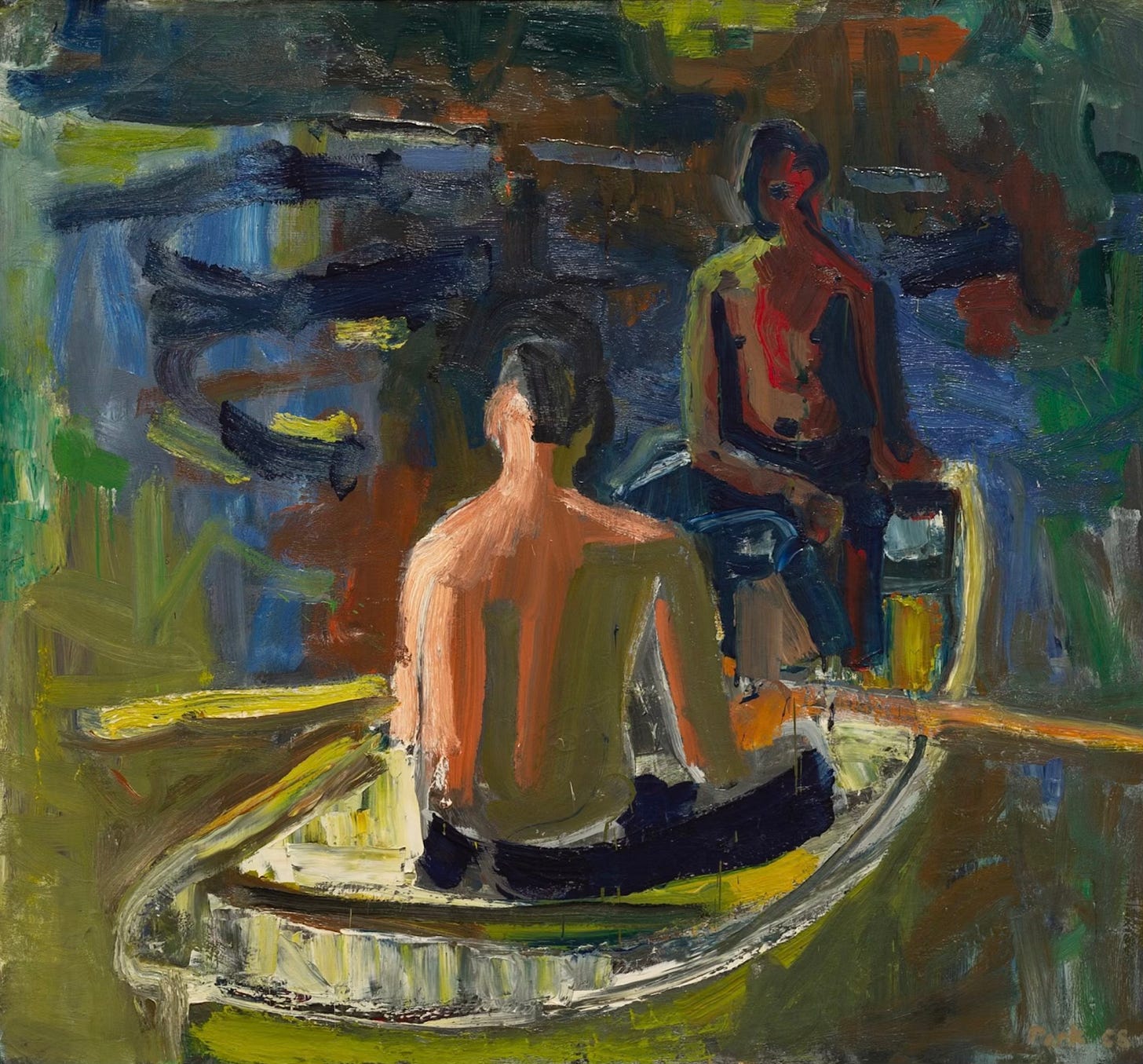

Art by David Park (1911-1960).

KEEP READING

FICTION

POETRY

EVENT

See Zachary Davis’s wonderful Wayfare piece "Caesar or the Cross” for a deeper exploration of a similar idea.

O. Michel, in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 4, ed. and trans. Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1967), 626–28.

Noeó means “to see in the mind’s eye,” as opposed to eidō, which refers to visual sight.