Divine Irony and Moral Theater in the Qur’an

The Qur’an is often approached as law, as doctrine, as poetry. But it is also theater, moral theater, staged not for entertainment but for revelation. The proud, the deluded, the heedless, the self-assured appear not as characters in a story, but as mirrors for us. And the voice that addresses them is not merely narrating, but interrogating. The Qur’an is full of questions that slice through pretense and expose the fault lines of false certainty.

This is where divine irony emerges. Not as cruelty, but clarity. The irony is not aimed at the sincere or the struggling. It is reserved for those who prop themselves up with illusion, those who confuse wealth with worth, desire with divinity, power with permanence. The Qur’an does not only correct them. It exposes them, often through rhetorical mockery that is as startling as it is unnerving.

“Shall We treat those who submit like those who do evil? What is the matter with you—how do you judge?” (Surah Al-Qalam, 68:35–36)

This question hangs in the air like a thunderclap. There is no need for God to raise His voice. The absurdity of the assumption speaks for itself. It is a moral axiom disguised as a question. In just a few lines, the illusion of spiritual entitlement is dismantled, and the reader is left with an uncomfortable silence: On what basis do you judge?

The Qur’an often turns the tables like this. It lets arrogance speak first, then answers it with devastating calm:

“Did you think We created you in play, and that you would not be returned to Us?” (Surah Al-Mu’minun, 23:115)

What could be more sarcastic than the idea that existence is a joke, that life is a toy, and that death is the end of the game? The question contains its own refutation. You feel the ground shift under you. The “you” is not just them. It is us.

Sometimes the irony is existential:

“Were they created from nothing, or are they the creators?” (Surah At-Tur, 52:35)

This is not a theological proof. It is divine satire. The idea that humans could create themselves is so absurd it does not need a refutation, only a pause. The Qur’an does this again and again. It does not only argue. It reveals.

“Have you seen the one who takes his desire as his god?” (Surah Al-Jathiyah, 45:23)

Here, idol worship is no longer external. It is internal. The deity is not a statue, but the ego. The irony is quiet and surgical. And it leaves us wondering: Where do we place our devotion? What do we truly worship?

The same word they once laughed at—Judgment, Afterlife—returns now not as metaphor but reality. Their mockery becomes the medium of their undoing.

And then, there is this:

“Or do you have a scripture that you study, which says you’ll be given whatever you choose? Or do you have oaths binding on Us until the Day of Resurrection, that you will get what you judge?” (Surah Al-Qalam, 68:37–39)

This is God in His sharpest rhetorical mode. Not cruel, but cutting. Here, the deluded become authors of imaginary scriptures, claimants of non-existent covenants. And the divine voice simply asks: Where is this coming from?

Such questions do not require answers. That is their genius. The Qur’an does not reason with arrogance. It reveals it to be ridiculous. And in doing so, it grants the listener an unexpected gift: freedom from delusion.

To read these verses is to be stripped of our disguises. The Qur’an does not humiliate the soul to condemn it. It humbles it to revive it. It names the absurd without denying the real. Even the world itself is unmasked:

“The life of this world is nothing but play, amusement, adornment, boasting among yourselves, and rivalry in wealth and children—like rain whose growth pleases the farmer, but then it dries and turns yellow, crumbling to dust…” (Surah Al-Hadid, 57:20)

What could be more ironic than mistaking what is fleeting for what is eternal? The world is not condemned. It is exposed. Its beauty is real, but it is also temporary, deceptive, easily mistaken for the goal rather than the path.

This is the Qur’an’s spiritual satire. It exposes the games we play with status, success, and superiority, not with scorn, but with sobering clarity. You chase what perishes, it seems to say. You boast over shadows. You compete in what will slip through your fingers like dust.

And once again, the divine voice does not argue. It asks:

“What is the matter with you? How do you judge?” (Surah Al-Qalam, 68:36)

The Qur’an does not shout over our distractions. It speaks through them, revealing their emptiness from within. This is divine irony, not mockery for cruelty’s sake, but mockery that heals by breaking illusion. The laughter it evokes is not dismissive, but awakening. It is the laughter of someone startled into seeing clearly for the first time.

In this moral theater, God is not merely Judge or Lord. He is also Witness, Unmasker, Truth-teller. And the question is never just what do others do wrong. It is what roles do we play in this theater of delusion. Whose script are we following?

But the Qur’an does not leave us in the ruins of our illusions. After the storm of divine irony comes the stillness of mercy. The same voice that exposes our pretensions also invites us to begin again. Over and over, we hear:

“And My Mercy encompasses all things.” (Surah Al-A‘raf, 7:156)

There is no permanent exile in this book. Only wakefulness. The Qur’an does not humiliate to punish. It purifies. Even the most scathing mockery is a kind of mercy in disguise. It breaks us open so that truth might enter.

“Say, O My servants who have wronged their own souls: do not despair of God’s mercy. Indeed, God forgives all sins. He is the Most Forgiving, the Most Merciful.” (Surah Az-Zumar, 39:53)

This is not a text of cold judgment. It is a book of fierce compassion. The divine sarcasm that cuts through pride is also what clears the way for grace. We are not mocked to be discarded. We are unmasked to be redeemed.

The Qur’an holds a mirror to the soul. But it also holds out a hand. And in the stillness after its searing questions, we are invited to return, to listen again, to rewrite the script we have been living by. Not as self-appointed judges. Not as boastful collectors of dust. But as servants, remembering the Real.

Yahia Lababidi, Arab-American poet of Palestinian descent, seeks to be a Muslim voice for peace. Author of over a dozen books, he explores themes of conscience, interfaith dialogue, and justice: most recently in Palestine Wail, a love letter to Gaza amid genocide.

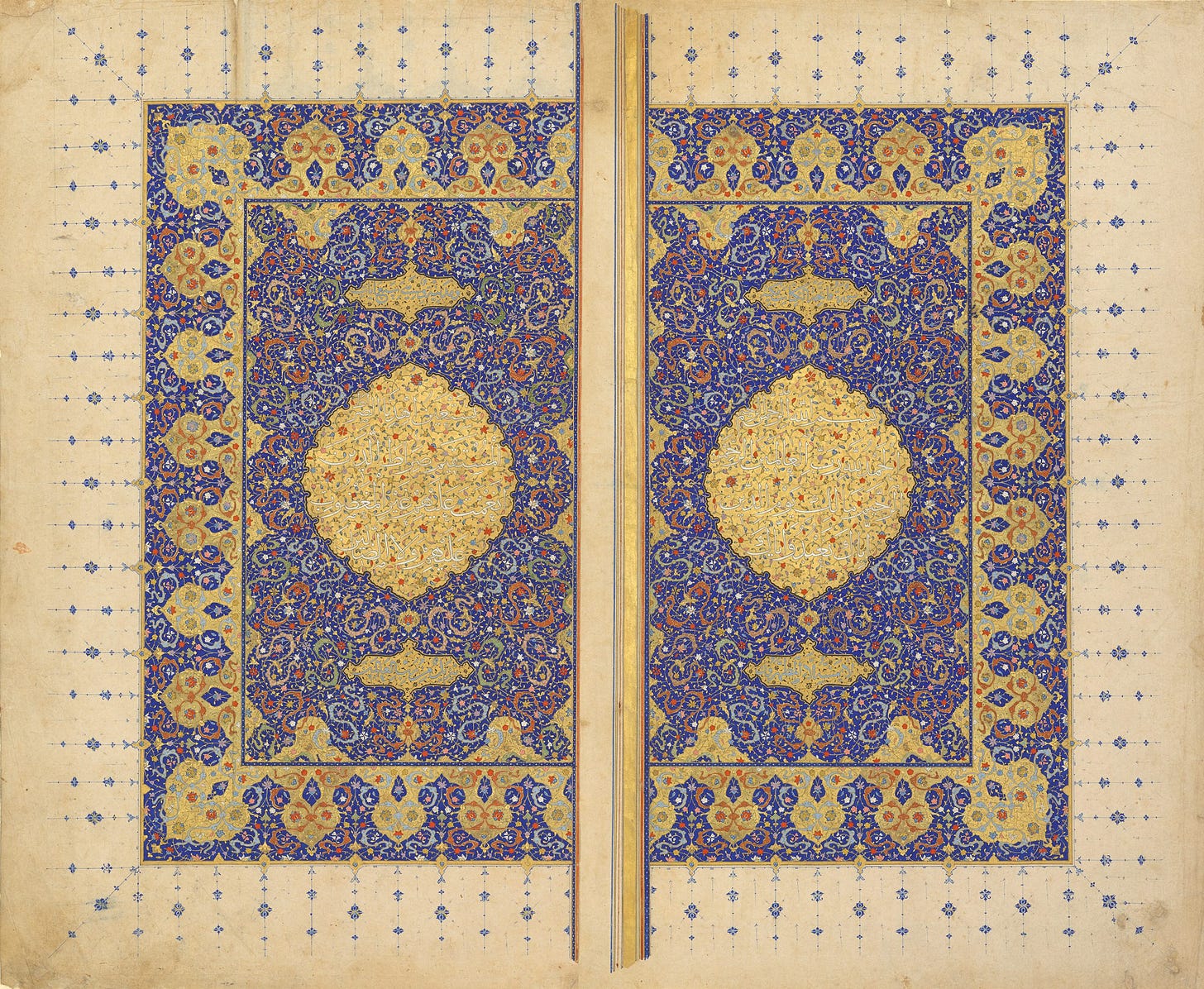

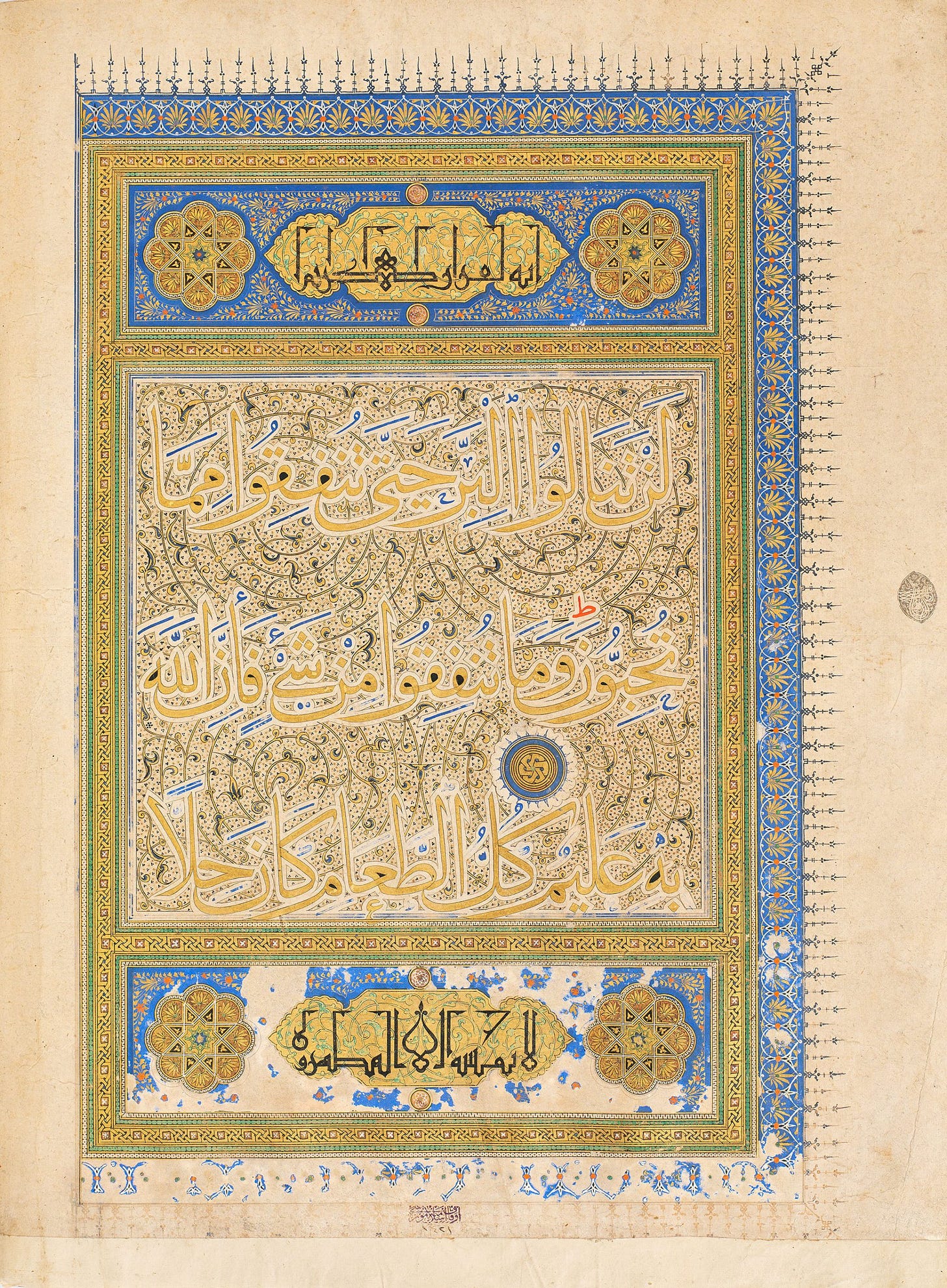

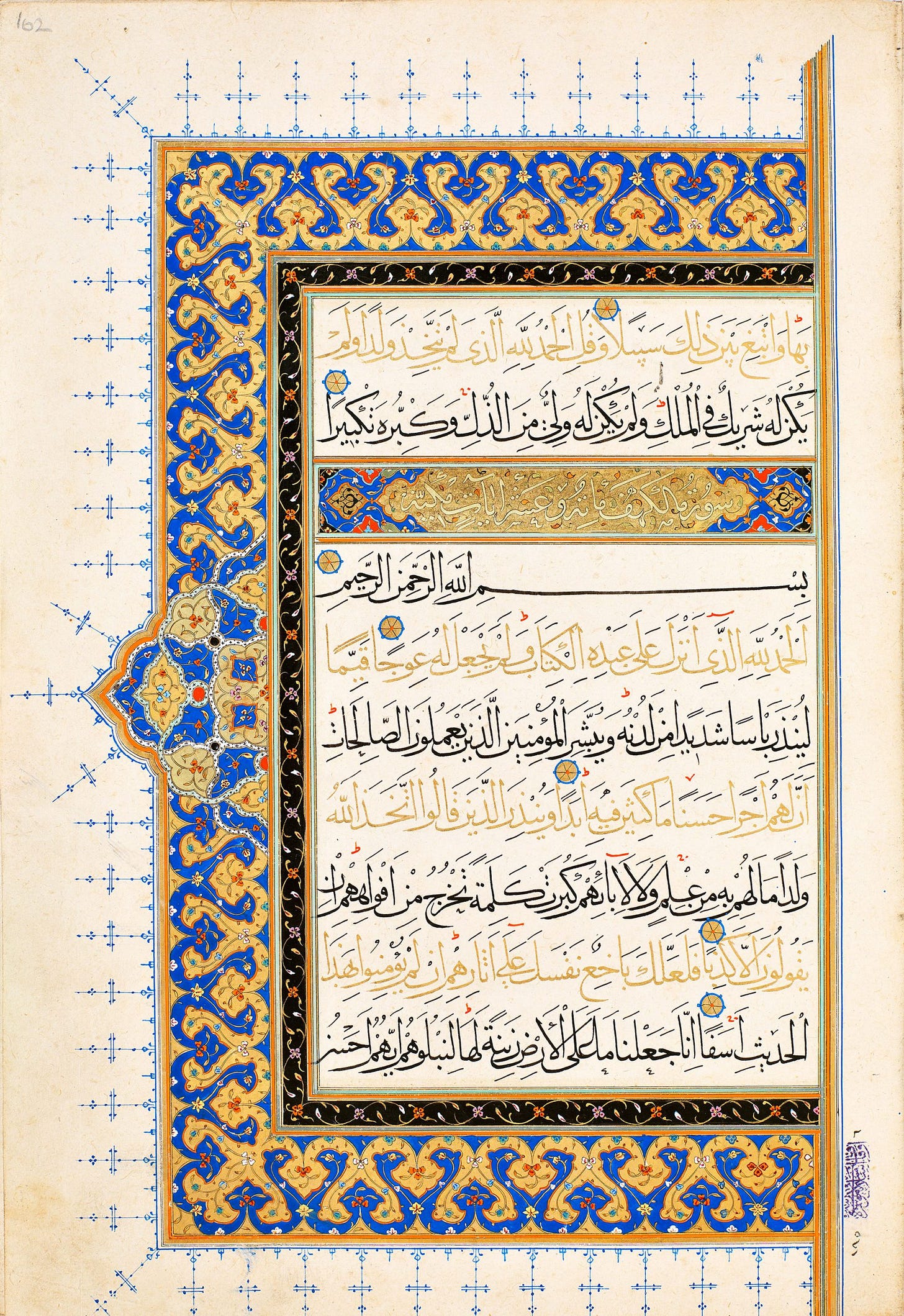

Art from The Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.

Thank you for highlighting the power of irony and absurdity as instruments to prepare the way of grace and mercy. The shift between the former and the latter is apparent in the passages you cite and amplifies the power of the rhetorical questions posed by the Qu'ran. 🕊️