Towing the Bishop

I was already in a bad mood when I saw the truck. It was a massive Chevy Silverado, complete with a Z71 package of off-road features, and it was parked in my assigned parking spot—not two yards away from the “Towing Enforced” sign written in bold, ominous red letters. Then there was me, idling in my inherited minivan in the middle of the parking deck, trying not to lose my cool.

My wife Rebecca and I were young newlyweds at the time, living in a 575-square foot apartment near Brick Oven in Provo. Our parking lot was notorious for illegal parking, and it was easy to understand why. We had prime real estate: right across from the soccer field and tennis courts, just around the corner from the Smith Fieldhouse, within walking distance of LaVell Edwards Stadium. In our first year of living there, I’d already been forced to call a tow truck three different times.

I got out and looked around. There was no one in sight. It was around 9:00 p.m. in early June. The sun had just set, but its angular pink rays were still putting their last brushstrokes on the tip of Y-Mountain. I considered my options.

On the one hand, our landlord was adamant that we enforce the towing policy. If we didn’t, he reasoned, it would just get worse. On the other hand, I could just find somewhere to park on the street for the night and avoid the hassle. But I’m paying $10 a month for this parking spot! Shouldn’t I be able to park in it?

The decision-making part of my brain lit up and bounced around like an old-fashioned pinball machine, testing different paths down the ramps while I used intellectual slingshots and flippers to reset my logic. I knew it would take a while for the tow truck to arrive, so maybe it would be faster to just park on the street, but I was exhausted. We were moving across the country soon, so our entire lives seemed consumed with cardboard boxes and saying goodbyes. I glared at the Silverado while the general stress of uprooting, endless errands, and an unknown future contributed to my irritation.

Every time I had done this in the past, the owners of the illicitly parked car had eventually come meandering out of the apartment complex before their car had vanished. I stood near the truck, waiting for someone to appear. I could already imagine them offering their smiley apology and explaining that they were just dropping something off, or whatever the excuse was. But no one came.

Reluctantly, I began the process—and it is a process. I called the number on the sign. They gave me a different number. I texted that number a picture of the truck’s license plate and a picture of it in my spot. I even had to send them a copy of our lease and an image of my driver’s license. They verified that the spot was mine. I waited.

I texted the landlord as well to keep him updated and he told me I could park in stall 26 until the tow truck arrived. I parked our van, headed inside, slumped on the couch, and waited for flashing orange lights to appear outside our apartment window.

Fifteen minutes passed. Thirty. Forty-five.

From my place on the couch, I suddenly saw two blurry figures out of my peripheral vision. I turned and looked across the courtyard just in time to see them enter an apartment on the third floor.

Wait, what if that’s the bishop?

That idea was enough to fire up the pinball machine in my cranium again. Our ward had been split about a week ago. We’d gotten a brand-new bishop, but I hadn’t met him because we’d been out of town visiting family. Maybe he was out doing ministering visits for the first time and hadn’t seen the “permit parking only” sign? The more I considered that scenario, the more likely it seemed. The last thing I needed was to accidentally tow the bishop’s car, so I found his number on the Tools app and sent him a text.

“Hey Bishop, if that Chevy Silverado is yours, it’s about to get towed!”

No response. I texted his wife too, for good measure. No response. The tow truck had to be getting close. Frantically, I decided to call them both. Neither of them answered.

I counseled with Rebecca. Should we go knock on that random apartment door? Wouldn’t they have checked their phones in between appointments? It had been over an hour by now. Maybe it wasn’t even them! I paced, stopping intermittently to squint out the window. From our vantage point on the first floor, I could see just a sliver of the parking garage and its upper deck. Nothing seemed to be happening, and no one came out of the third-floor apartment.

The flashing orange lights finally arrived around 10:00 p.m. I watched as the tow truck angled awkwardly and backed into the parking lot. I checked my phone—no messages. Thanks to the tennis court floodlights, I could see the trees along south campus, their leaves shimmering as they reflected artificial light against the obsidian sky. The tow truck pulled away, its pulsing neon glow fading into the distance. Hesitantly, I stepped outside to peek at our parking spot. Sure enough, the Chevy Silverado was gone. The streets were quiet and empty. I reparked our van and headed back inside.

Just at this moment of great alarm, my phone vibrated. No sooner had the message appeared than I felt my breath catch in my chest. The text was from the bishop’s wife.

The Chevy Silverado was theirs.

When I came to myself, I immediately had two distinct thoughts. The first was the realization that—by trying to send those courteous warning messages—I had unintentionally revealed myself as the heartless, tow-truck-calling grump. The second thought was about my dad—who was also currently serving as a bishop at the time—and how I could so easily picture him doing something similar: parking conveniently before a quick visit and hoping for the best. I realized that the very least I could do was go out and offer them a ride, no matter how awkward it would be.

I found them standing near the dumpster. Bishop was talking with the tow company on the phone, sounding justifiably frustrated. The bishop’s wife tried to laugh it off and reassured me that it was all okay. They were being good sports, but I knew that I’d made their night much harder than it needed to be. Whatever righteous indignation I had been feeling about the Chevy had been completely reversed. I felt terrible.

They were reluctant to accept my help, but I eventually convinced them to let me give them a ride to the impound lot. I couldn’t imagine making them book an Uber since I’d already cost them a towing fee. The drive was an awkward combination of small talk mixed with overexplaining and apologizing on both sides. “Don’t worry,” I joked. “We’re moving in a few weeks, so you’ll never have to see us again.” It was almost 11:00 p.m. by the time I got back home. Ironically, I’d made my own night harder than it needed to be too.

In hindsight, I’ve often puzzled about what a perfect storm it was. If they hadn’t parked illegally, none of this ever would’ve happened. If I had just parked on the street and taken a walk, it wouldn’t have happened either. If I hadn’t texted them, they never would’ve known it was me; they would’ve had to find their own way home. And, if it had been anyone other than the bishop, I couldn’t have tried to warn them anyway. But it happened exactly like that, in precisely that order. The bishop and his wife even confessed that, during one of their ministering appointments, another couple had warned them that they were likely to get towed if they parked there. We both had our chances to change the outcome.

I’d also be less than honest if I didn’t admit to feeling some consternation after the fact. As I struggled with my tow-truck remorse, I could feel myself reverting to rationalization. They were the ones who broke the law. I was just doing what my landlord asked me to do and parking in a spot that was rightfully mine! Why, then, did I feel so awful about all of it? Was it just because it was the bishop? But why should I treat the bishop differently than anyone else? And bishops aren’t above the law, are they? No matter which way I tried to square it, my narratives of fault and blame just weren’t lining up.

I’ve told this story to friends and family many times, but it often surprises me how they react. My brothers were adamant that it was the bishop’s fault. “You can’t park illegally, period!” they said. My uncles who had been bishops felt differently, sympathizing with the demands of that calling. Some were mortified at the idea of calling a tow truck on someone, while others chided me for sending a self-incriminating text. It’s a complicated scenario. Obeying the law is definitely important; it’s in the twelfth Article of Faith. But for some reason, towing the bishop feels more vicious and un-Christlike than an innocent little parking violation. Beyond lamenting Provo’s miserable parking situation, what would the moral of this story be? Justice and mercy? Love and law? Debtors, creditors, and mediators? Who plays which role in each version?

Perhaps it was just another instance of two people doing their best, both of them making mistakes, hurting themselves and others in the process, but also offering each other some reciprocal grace and mercy as well. After it was all over, I definitely had a good laugh. So did anyone who heard me tell the story. In fact, maybe laughter is just something else that happens when justice, love, and mercy meet in harmony divine.

Isaac James Richards has published creative nonfiction in LIT, OxMag, and elsewhere. He's received awards from both the David O. McKay and George H. Brimhall essay contests.

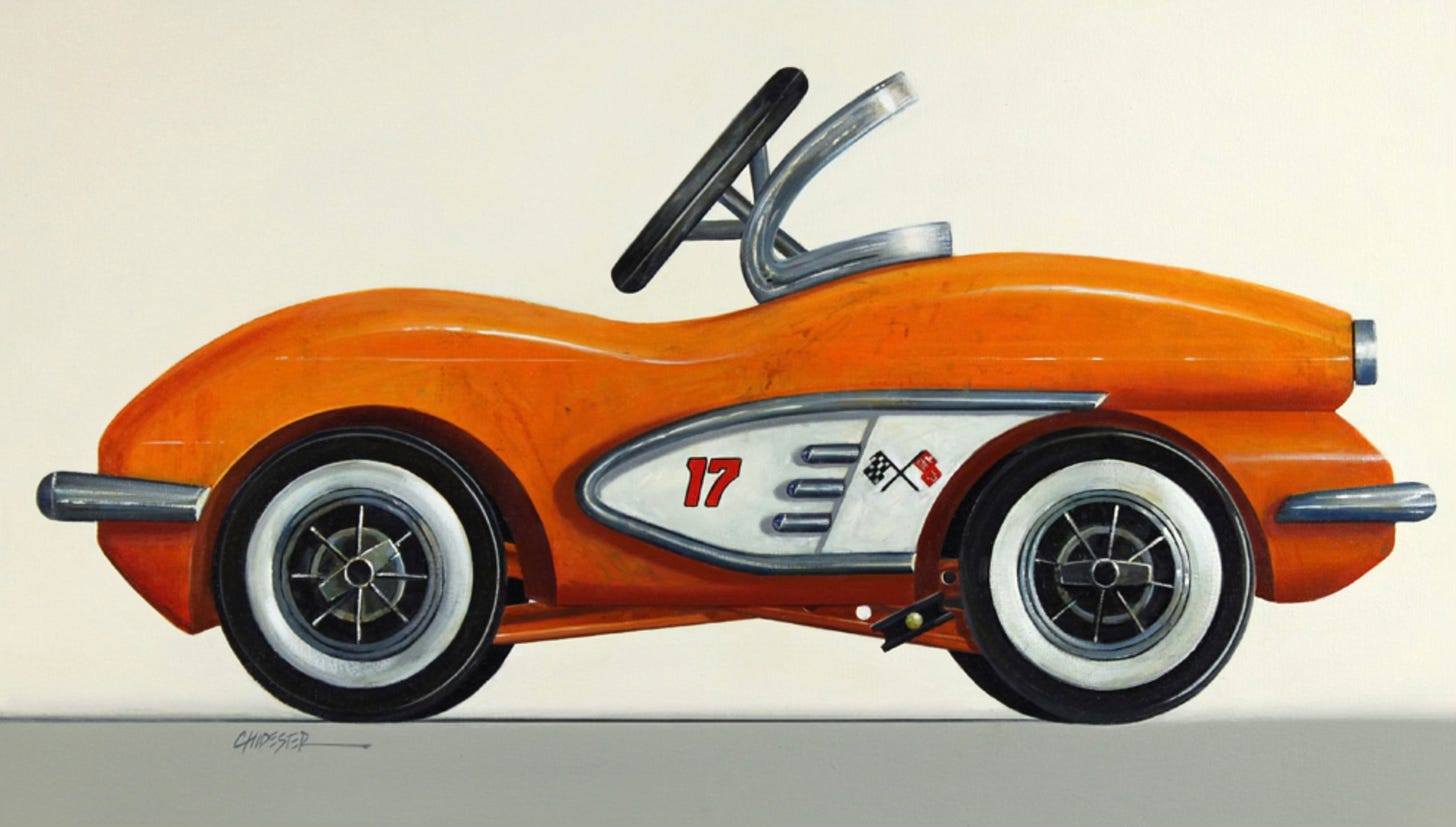

Art by Wendy Chidester.