This is the fifth essay in the “Covenant Life” series, where we are exploring together why covenants matter and just what they mean and do. Please see previous essays: Rising Together, My Side-by-Side God, Uphill on the Yellow Brick Road, and Toward a Practical Theology of Sealing.

Turns out Jesus really is homeless—and most of us, myself included, keep walking right past him.

On a crisp fall morning in New York City several years ago, my friends and I ate a quick breakfast on the steps of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. I had half of a bagel sandwich and some fruit left over, and I noticed a man sleeping under a tattered brown tarp on a bench nearby. “I’ll leave this food for him when he wakes,” I thought.

As I approached the bench, I felt strangely uneasy. The tarp covering the man did not move. Was he breathing? Was he ok? Was he alive?

I moved closer.

Oh! It was a statue.

And then, I saw, and was immediately overcome with a different sensibility—one of intimate attention. The feet of the statue’s enshrouded body bore the mark of nail prints.

This was a statue of Christ.

I instinctively sank to my knees. Arrested by the beauty and the challenge of encountering a depiction of Jesus in such a distressing disguise, I knelt for several awe-filled moments before remembering the crumpled paper bag still clutched in my hands. The sausage-egg-and-cheese bagel inside now felt like a sacramental offering, urging me to act.

Beneath the low hum of the city in a busy subway station mere moments later, I saw him: a man, huddled near a steam vent, its warmth rising like fragile mercy in the cold. Wrapped in layers of worn fabric and shadow, he muttered to himself, the words fragmented—half prayer, half memory. Around him, his encampment was a patchwork of belongings: tattered blankets and crumpled bags, shaped into the semblance of a life. He rocked slightly in the dim flicker of the overhead light, lost in a world not entirely his own—but not entirely ours either.

Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these . . . ye have done it unto me. Again, I knelt, and seemed to be looking into the eyes of Jesus himself. “Sir,” my voice trembled, “this is for you.”

I have a confession: I am often restless in the temple. This restlessness arises from a disquieting sense that what is meant to bring us closer to God instead has the potential to become a polished icon of separation from the suffering Christ—from the brokenness, benches, and bagels. If the temple is only a place of sacred worship and stillness for ourselves and for the dead, but not a catalyst for Christian engagement in the world, are we missing the mark? Covenants are made in the temple but are not kept or lived there. When temple worship becomes the ultimate end instead of a provisional stop on the journey, have we recreated the temple as an idol? And in so doing, have we averted our gaze and diverted our energy from the holy noise of mourning and human need in the world just outside its doors? Perhaps the restlessness I feel in the temple is precisely its salutary call to get out into the world and to live the covenants renewed therein. It is the sacred charge to live what the gospel teaches us to believe.

If we view the five sacred covenants made in the temple as ascending in significance, then the Law of Consecration would represent the highest law. But if the covenants are viewed as a symmetrical line of five, it is the third that stands at the center, neither first nor last, but the hinge upon which balance turns. It is the axis, the heart, the fulcrum—flanked by two on each side like sentinels or witnesses. At the center, three is the moment of arrival, the still point in the turning world. Three is where meaning gathers. In storytelling, it is the climax. In rhythm, it is the beat that grounds the pattern. And in Biblical numerology, three is trinity—wholeness expressed in triad form.

The third covenant that we make in the temple is the Law of the Gospel. The Higher Law. The New Covenant. Jesus’s “Kingdom Manifesto.”1 It is the only covenant that bears the shape of a cross: with it, we promise to embody the two great commandments spoken by Jesus—the vertical command “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, and mind,” and the horizontal command “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Forming not only the heart of Christian discipleship but the very shape of the cross itself, the Law of the Gospel is an invitation to fashion our lives into a cross of love. The breathtaking invitation in this covenant quickens and expands my theological and spiritual imagination.

Jesus’s “higher law” teaching is often synonymous with his Sermon on the Mount in Matthew’s gospel (5:1–7:29). This sermon, unlike any of Jesus’s other messages, is an extended monologue that contains no parables. Although many assume the intent of this “Kingdom Manifesto” is to answer the question of how one attains a secure place in a heavenly afterlife, I see Jesus turning our attention away from life after death and towards this world—here, now, in this aching masterpiece of creation, fractured and full of grace. In giving us the Law of the Gospel, Jesus is inviting us not to linger in familiar patterns of thought, but, instead, to behold with renewed minds the unfolding of the Kingdom of God in the present moment, where righteousness reveals itself in the rhythm of a life aligned with divine love.

Jesus opens his sermon with the Beatitudes—eight statements that disclose what kinds of people he considers to be “living right.” His radical subversiveness is immediately on display, disarming traditional assumptions. Instead of naming the rich, the pious, the bold, the clever, the successful, the victors, or the powerful as deserving of blessings, Jesus lays the groundwork for his surprising and disruptive kingdom. “Blessed are the poor, the meek, the merciful, the pure in heart, the peacemakers, the persecuted.” Christian author Brian McLaren suggests that “Jesus builds on this disruption: his followers are not simply normal people with a certain religious preference. No, they are radical participants in a high-commitment endeavor—compared to salt, which flavors and preserves meat, and to light, which penetrates and eradicates darkness.” Clearly, Jesus is concerned with the whole of this life, not merely the salvation of souls through an “evacuation plan”2 into the next.

The sermon continues with Jesus declaring his divine purpose: he came not to abolish but to fulfill the law. He issues a statement so bold and so disruptive, it surely was insulting to the religious leaders, “snug and smug in their insider status:” For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” By first attesting his faithful loyalty to Jewish law, Jesus invites his followers not into lower standards but into a higher, deeper moral life. Repeating again and again the provocative phrase “you have heard that it was said . . . but I say to you,” Jesus calls us into a transformative way of living that not only fulfills the intent of the law, but vastly exceeds the “external conformity and technical perfection” of the Pharisees’ fortress of rules. Jesus refuses to fixate on conventional purity codes, external wrongdoing, and what is deserved. Instead, he stretches our spiritual imaginations towards something far deeper: radical non-violence, reconciliation, and a transformation of social relationships.

I think again of the Homeless Jesus statue, metaphorically reflective of the subversive ethics Christ proposes in his Sermon on the Mount. He explores how we treat others, particularly the poor. He teaches us how to trust God, and he cautions us that our words must become living, embodied, and grace-filled action. The Law of the Gospel is centered in relationships and responsibility, making its focus much more socially conscious than the individualistic morality that so often occupies center-stage. Biblical scholar Obrery Hendricks notes that both justice and righteousness, according to Jesus, are based on social relationships rather than personal piety or on individual conformity to ritual and liturgy. “In fact,” Obrery writes, “in the Hebrew scriptures there is no word for ‘individual’; there is only the plural term for ‘people,’ that is, community. For this reason, for any social, religious or political endeavor to rightly claim to be consistent with the Biblical tradition, it must have at its center justice for all people regardless of class, gender, color, or national origin.”

Would any Christ-lit imagination or covenantal heart ignore the plight of our sisters and brothers in the world, whether it be in migrant detention camps in Florida and El Salvador, in the brutal conditions of our children in Gaza, Sudan, and Ukraine, or in the many forms of systemic inequality that prevent human flourishing and perpetuate poverty, abuse, marginalization and a diminished sense of agency? As covenant disciples, are we not continuously called to understand and live Jesus’s theology of solidarity with the poor and oppressed? I believe the Law of the Gospel means taking seriously the reality of the suffering in the majority of our world.

As such, my encounter with the Homeless Jesus and its resulting, pentecostal experience with the man in the subway station was only a point of entry into a covenantal embodiment of the Law of the Gospel. Latter-day Saint scholar, psychologist, and writer Frances Menlove provocatively illustrates this: “As followers of Jesus, we are called to not only care for those who are suffering but also to transform the conditions that bring about suffering.” In my study of Franciscan theology, I encountered the phrase “See, Discern, Act,” a method for engaging faithfully and thoughtfully with the world’s social, economic, and political realities. Seeing the arresting statue of Jesus and discerning its moral application to the unhoused was not enough. That experience must also propel me to act: to question the systems and circumstances that result in a person having to sleep on a park bench in the cold or cramped in a dank station of the New York City subway system.

Living out the Law of the Gospel is the journey of a lifetime. The way in which we make covenants, both for ourselves and for the dead, is scripted and uniform in the temple, but the way we negotiate how our covenants will be lived is as diverse as we are created. I feel called to live the Law of the Gospel by being willing to bear witness to the values of the Kingdom of God—not just in private faith but in public life—where systems, policies, and power impact the vulnerable. I feel called to accept the cost that often comes from speaking out for those whose voices are silenced—immigrants, refugees, the LGBTQ community, women, the unhoused, the poor, the incarcerated. Do I, bearing a conscience shaped by Jesus’s moral and ethical teachings, not also bear an equally conscientious responsibility to take action through the way I serve, donate, vote, and support legislation and public policies that promote justice, equity, peace, and the common good? May I, I pray, ever inhabit the courage to show up physically and publicly in spaces of protest, healing, and advocacy—not as a savior, but as a co-sufferer and co-worker for justice. May I too, I pray, bear our collective burden of learning about systemic injustice: racism, economic inequality, environmental degradation, and historical wounds. May my prayers represent not just daily personal claims for my own private comforts—no, may they also rise up as an act of public witness and intercession, with courage to disturb the unjust status quo. If I am to one day stand before my Maker, I must be willing to confront and challenge inequitable norms, even within the Church, and speak truth in love—especially when it costs me.

Humbled before such statues of Christ and restless in his temples, may each of us live here and now to remake the world into the very heaven his law will bring: a living, breathing Zion for all. This is the Law of the Gospel, and it might be the most authentically saving message we have.

Jenny Richards recently received her Masters of Theological Studies degree from the Franciscan School of Theology at the University of San Diego. She will begin a chaplain residency in Salt Lake City in fall 2025. You can find Jenny’s musings here: Jenny Richards, @walkingtheroadtojericho.

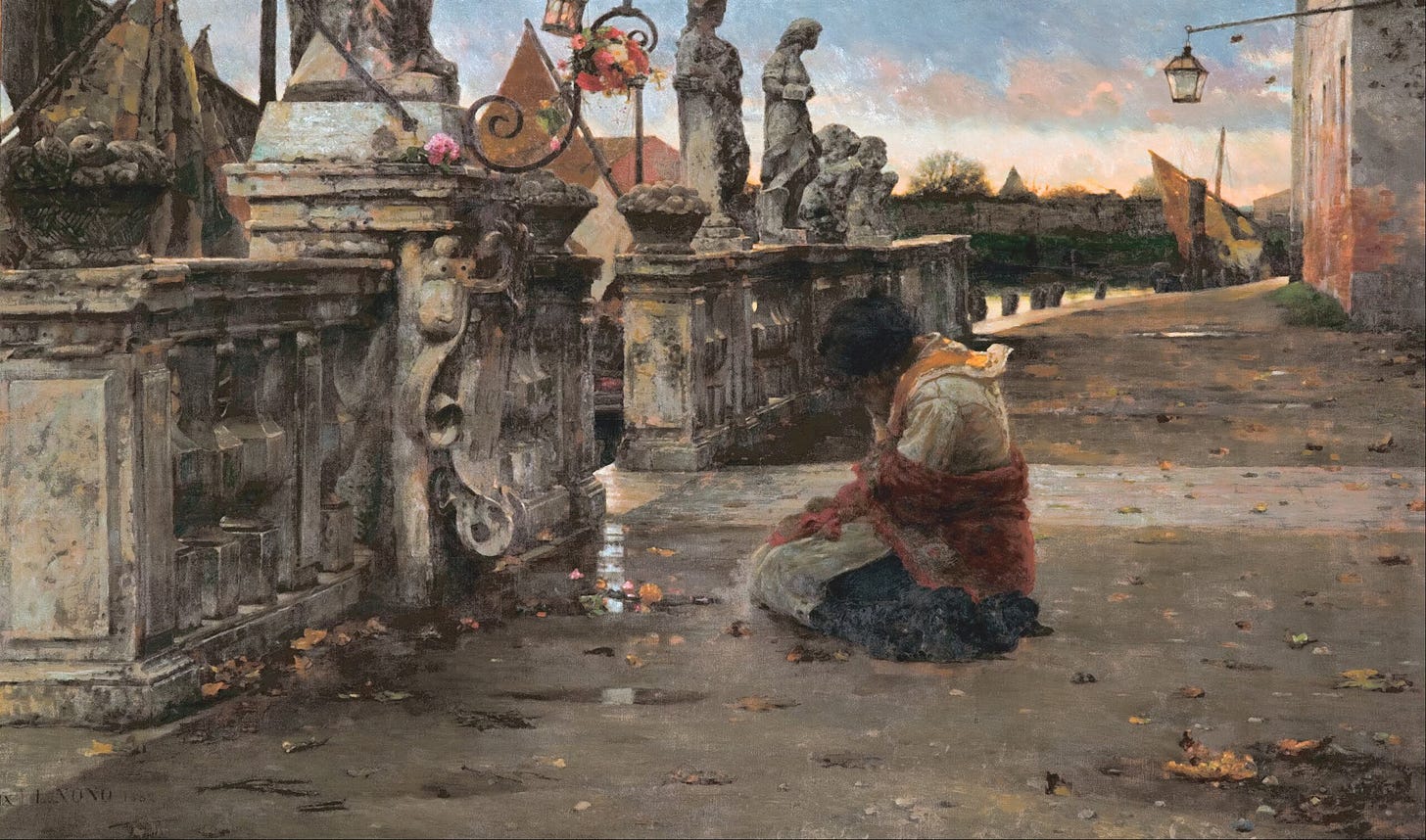

Art by Luigi Nono (1850-1918).

Brian McLaren, The Secret Message of Jesus: Uncovering the Truth that Could Change Everything (Thomas Nelson Inc., 2006), Chapter 14.

Adapted from Richard Rohr, Dancing Standing Still: Healing the World from a Place of Prayer (Paulist Press, 2014), 53–55.

Thank you so much. This was a wonderful article. You put into wonderfully descriptive language the thoughts and feelings of my heart. I can't wait to share with my siblings a d friend group.

So beautiful. Thank you. Thank you.