This year may hold more political discussions, arguments, and debates than any other in history. Several news organizations have noted that billions of people, about half of the world’s population, are surrounded by political contests in 2024 as their countries hold elections. Some of these political contests are prompting heated rhetoric, disillusionment, and even an assassination attempt in the United States.

As I watch these campaigns play out on social media, I remember an incident that changed the way I engage with politics. It began when I wrote a scathing, sarcastic Facebook post about my “favorite quotes” from supporters of a politician I opposed. Each quote was paraphrased, exaggerated, and followed by mockery.

And almost every one originated with a friend—here I’ll call him Russ. Before I published, I changed my privacy settings so that the note would be hidden from Russ. I clicked “post” and went to church for Saturday night dodgeball.

Later that night, I checked Facebook to see what kind of laughs my commentary was generating. To my horror, one of the first comments was from Russ. The privacy setting had failed. “Hey, most of these quotes are from me!” he wrote. I felt like pulling my hair out. This wasn’t supposed to happen.

Unfortunately, Russ and I are far from alone in having a political controversy hurt a friendship. The dynamics of social media reward posts that attack an opposing partisan. In 2020, nearly half of all adults in the United States stopped talking to someone else because of politics. Several studies have shown that Thanksgiving dinners end sooner if the family and friends gathered to give thanks do not agree on politics. In the current election cycle, I see tense conversations going on, and on, and on, often involving Latter-day Saints sparring against each other.

When I read Russ’s comments on my scathing post, I felt condemned, found out. I deleted the post, wrote a public apology, and called Russ to apologize directly.

The next morning I woke up with five words echoing in my mind: “Speaking the truth in love.”

Those words played on repeat as I donned a white shirt and tie, drove to church, took the sacrament, and listened to the talks and lessons. After church, I searched online and found the phrase in Ephesians 4, where Paul describes the purpose of the church organization:

“For the perfecting of the saints . . . for the edifying of the body of Christ: . . .

That we henceforth be no more children, tossed to and fro . . .

But speaking the truth in love, may grow up into him in all things, which is the head, even Christ:

From whom the whole body fitly joined together and compacted by that which every joint supplieth … maketh increase of the body unto the edifying of itself in love.”

Reading these words in context, I realized that I had done at least two things wrong in my Facebook interaction. First, I had not spoken the truth. I certainly expressed my opinion about political truth, but I paraphrased my friend’s words unfaithfully, twisting them to make the joke sharper, the knife deeper.

Second, even to the extent that I did speak the truth—I honestly believed the point I was trying to make, and I still hold to many of the same ideals—I did not speak the truth in love. Influenced by national talk show hosts and comedians, I was more interested in drawing laughs from those who agreed with me than having charity for someone who disagreed.

Beneath the surface of Ephesians 4 are two Christian virtues that could have helped me refrain from alienating a friend. One is humility. In order for us to “be no more children,” we need to “grow up into [Christ] in all things.” Because we have room to grow, we must learn. “We know in part” (1 Corinthians 13:9), but God knows all. We must be humble to grow.

It is a kind of humility that Elder Robert S. Wood of the Seventy learned in graduate school. In a 2004 talk, he described writing an essay to criticize the ideas of a political philosopher he disagreed with. His professor asked him to rewrite the paper to focus on presenting the strongest argument in favor of the philosopher’s ideas before criticizing them.

As he revised the paper, his views changed. “I still had important differences with the philosopher, but I understood him better, and I saw the strengths and virtues, as well as limitations, of his belief,” he said. By seeking the truth in humility, he learned from a philosopher he disagreed with and strengthened his grasp on the truth.

Elder Wood’s story also exemplifies charity, another virtue we see in Ephesians 4. Paul’s letter reminds us of the importance of not just saying what is true, but doing so in love while seeking common ground. “Till we all come to the unity of faith,” the church—the body of Christ—must edify, or strengthen, itself in love.

The scriptural descriptions of charity stand in stark contrast to most political discourse, which is more focused on tearing down another side. “Charity suffereth long,” and this must include bearing with the stark disagreements we may have with the people with whom and to whom we minister. Charity “is kind,” and kindness leads us to kind acts that cross over disagreements. “Charity vaunteth not itself,” in contrast to political pride. Charity “seeketh not her own,” and is not concerned with scoring political points with a quick jab or an insult. Charity “rejoiceth in the truth” even when that truth may contradict the party line.

Joseph Smith seems to have been pleading for this kind of charity when he said that if his peers in Palmyra had “supposed [him] to be deluded,” they should have “endeavored in a proper and affectionate manner to have reclaimed [him]” (Joseph Smith History 1:28). As he learned through his leadership in the church, power and influence came “only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned” (Doctrine & Covenants 121:41). When sharp critiques were required, he learned, they must be followed by “an increase of love” (Doctrine & Covenants 121:43). When he forgave William W. Phelps of betrayal, he did so with “humility and love unfeigned,” imploring: “Come on dear Brother since the war is past / For friends at first are friends again at last.”

Moroni and Pahoran offer an interesting case study of political disagreement (Alma 60-61). Moroni did not love shedding blood, but he did not shy away from war. On the other hand, Pahoran, the chief judge, retreated from Nephite rebels and doubted whether fighting them would be justified. When the rebels impeded the Nephite army, Moroni blamed his chief judge and threatened a military coup. It was not the most charitable choice. But Pahoran responded humbly and charitably. “You have censured me, but it mattereth not,” he said. “I am not angry, but do rejoice in the greatness of your heart.”

Can you imagine how their exchange would have played out on social media? Moroni might have posted a rant complaining about the chief judge and issuing his threat. Before Pahoran even checked his notifications, Moroni’s message would go viral under clickbait headlines like, “Army General DESTROYS Chief Judge.” In media echo chambers, Moroni and Pahoran might dig in rather than defuse and reconcile. They did not live in our social media era, but they did live in an era preserved in scripture. We can learn from them how to engage with humility and charity.

To cite a more modern example, in the winter of 1964, while the U.S. was still reeling from a presidential assassination, newly inaugurated President Lyndon B. Johnson refused to comment on his opposing party’s upcoming primaries. “I hope to keep as free from politics as I can, as long as I can,” he said. But the next day, Everett Dirksen, the leading senator of the other party, vowed, “There is not going to be a political truce. … You don't use sponges to throw at somebody when you go into that kind of a contest.” But the two were friends, and within a few months Dirksen was helping to pass a signature civil rights bill urged by the president. He could have stonewalled the bill to deny the opposing party an election-year victory. Instead, he found common ground. Even though they disagreed on many issues, the two remained collegial and collaborative.

Unfortunately, my friendship with Russ did not follow the same path as those of Joseph Smith and William W. Phelps, Moroni and Pahoran, or Lyndon Johnson and Everett Dirksen. My politically divisive Facebook post happened at a time when Russ was drifting away from the church. My prideful and unloving political expression did little to help. At one time, he had listened to General Conference over the phone in a hospital while I held my phone up to my computer speaker. Other times, we’d had late-night phone calls to talk through his difficult gospel questions. But now some of those calls were replaced with political disputes. Within a couple of years, we had severed ties. I cannot help but wonder how his life and mine might have turned out differently if I had been more humble and charitable.

But I do know how my life changed because of that experience. I started trying to understand and learn from those who disagreed with me in politics and religion. I learned to look for common ground instead of seize upon differences. I started to speak up for those opposed to me politically, especially when I saw their views were misrepresented and maligned. Occasionally, people on one side of the political aisle have reached out to ask me to help them understand an argument on the other side.

As political rancor drives people apart, President Dallin H. Oaks has shared a vision for the role that Latter-day Saints can play in politics: “On contested issues, we should seek to moderate and unify.” Moderating does not require us to switch sides, or adopt a middle-ground political view. Instead, it calls on us to moderate discussion, perhaps like a debate moderator—someone who ensures that views can be expressed and exchanged in a particular manner. The unity we seek might not be a unity of belief, but a unity of charity for all.

While social media algorithms amplify disagreement and drive people apart, Latter-day Saints have the opportunity to heal those rifts. We can seek the truth in humility and speak the truth in love, creating dignified difference. If we embrace these virtues, perhaps Thanksgiving dinners will last a little longer this year, even when we voted differently than those with whom we break bread. Perhaps relationships once ended over politics can be mended, so friends at first can be friends again at last.

Bryan Gentry writes nonfiction on topics including personal development, psychology, open-minded discourse, and faith, as well as fiction and poetry. A graduate of Southern Virginia University, he lives in Columbia, S.C., with his wife and children.

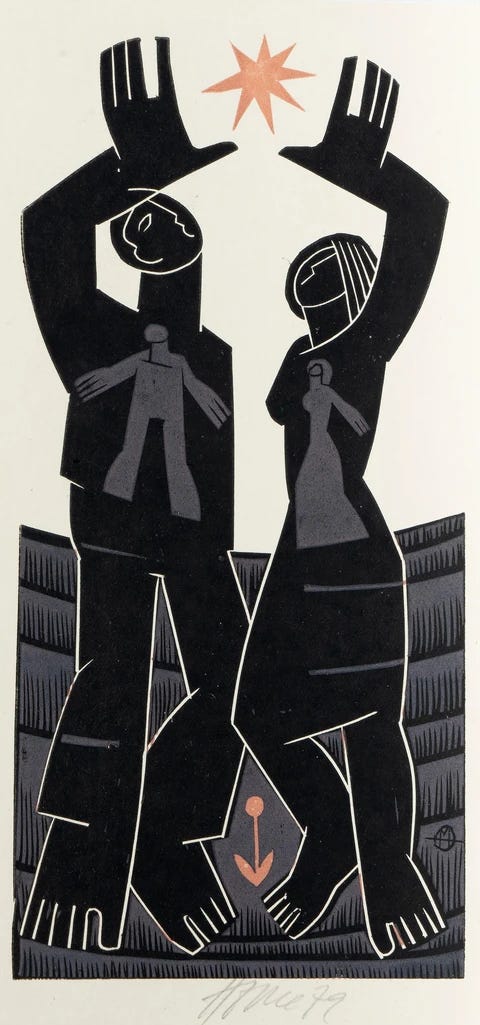

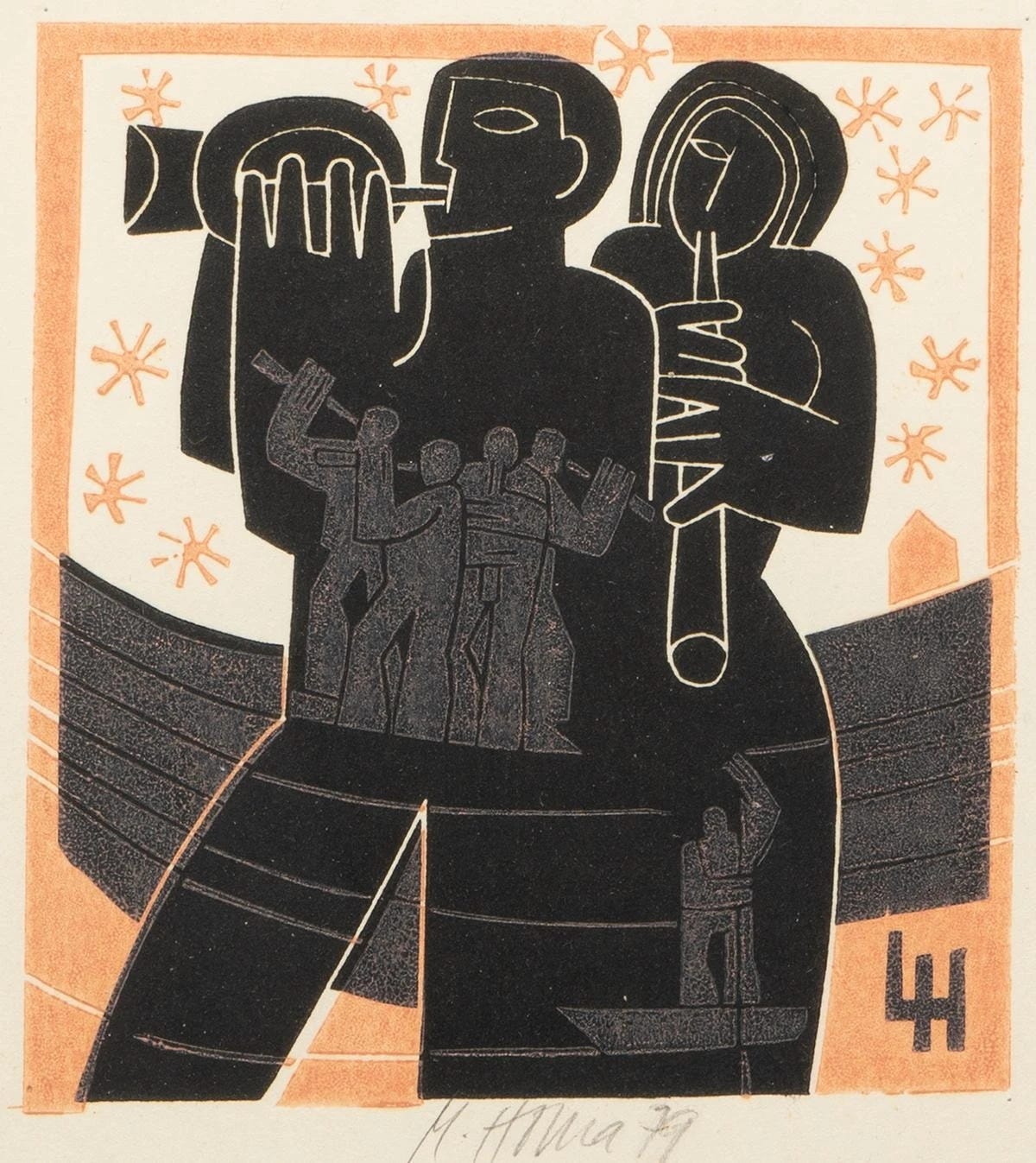

Art by Miroslav Houra.

This is the third installment in the Wayfare series “How to Think Politically.” The first is here. The second is here. If you are interested in submitting your own reflections for consideration toward future installments, please review and submit through this form here.

Issue 4 Preview

Subscribe today to ensure you get Issue 4 delivered to your home!

Also be sure to join us Friday Nov 15th at The Compass Gallery in Provo to celebrate the new issue.

NEWS

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints recently announced the rollout of new garment options for members in hot and humid climates. Noticeable for their dress slip and sleeveless options, these options will be progressively made available throughout the Church’s distribution regions by the end of 2025. The Salt Lake Tribune captures responses from members and scholars here.

The Interpreter Foundation is pleased to offer two seminars from noted scholar Dr. Margaret Barker, a friend of the faith, covering developments to the Hebrew scriptures and their impacts on Christian and Jewish religious history. Her presentations will be on two successive Saturdays, November 9 and November 16, 2024, both beginning at 11 a.m. Mountain Time. Each seminar will feature an illustrated lecture for approximately 50 minutes followed by 15 to 30 minutes for questions. The seminars are free but registration is required.

The Tree of Life Sculpture Garden at Thanksgiving Point, UT has officially opened, featuring over 130 bronze statues depicting scenes from the Bible and Book of Mormon, with 5 scenes of Jesus Christ. The garden’s sculptor, Angela Johnson, embarked on this massive venture with a desire to testify of Christ and present the Book of Mormon as a record of Him.

Mormon Scholars in the Humanities & the Association for Mormon Letters have extended their deadline for paper submissions to October 31st! Their conference will be held from May 28-30, 2025, at Snow College in Ephraim, Utah.

Good on ya for owning it. I hope Russ finds peace.

I live in a very blue area (our county voted for Biden 80%). But when my truck broke down, the first guy to stop was in a vehicle with Trump and NRA stickers. Thanks for the reminder to be careful about making comments not in love. I deeply appreciate it.

What a beautiful reminder, Bryan. Thanks for writing and sharing this essay.