In this second installment of our series How to Think Politically:

Shayla Frandsen seeks out healing helpers along toxic political pathways;

Donald K. Jarvis reflects on widening and deepening our political thinking;

Charlotte Wilson summons the courage to stay in the fray;

Chad Ford spells out the art of politics as dangerous love; and

Stacie recounts how she came to see her vote as sacred.

1. Look for and Serve alongside the Healing Helpers

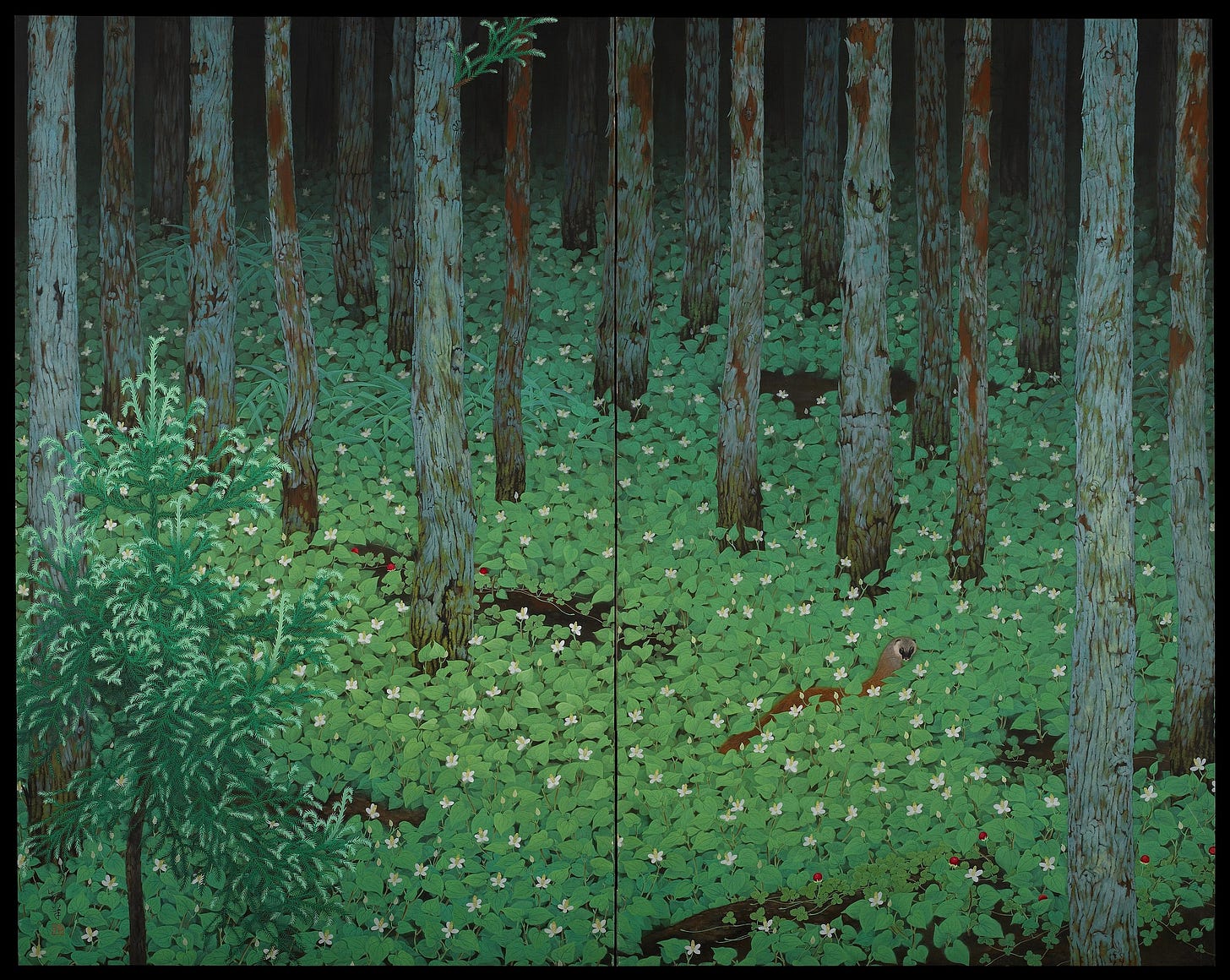

Let’s say you're walking in the woods and stumble upon some poison ivy. Disaster! Or is it? Very often, a natural remedy for poison ivy will be growing nearby, close to the initial source of harm. Jewel weed, burdock, plantain, yellow dock: one of them will usually be around, patiently waiting. These plants (or others on my plant identification app) often wait for their leaves or stems to be picked and rubbed on the wound, a beautiful source of natural healing for those who have eyes to see them. Whenever I’m overwhelmed by the seeming onslaught of discouraging political news or the calumnious machinations of powerful men who do not seem to have the interests of anybody but themselves in mind, I try to remember this gift of knowledge from our Mother Nature. The harm is evident, but with a closer look, the healing is too. It’s often growing right nearby.So is it in politics. There are people who feel just as dismayed and discouraged as I am, and yet they too grow where they are planted, whether by running for office, encouraging people to vote, pushing for reform, or founding groups to fundraise, educate, or encourage political awareness. They’re burdock and jewel weed made real, embodied healers who inspire me to create engagement of my own. Many times these people emerge from oppressed groups, ready to step into the political vortex to claim the rights for themselves and others whom society often overlooks. These people inspire me to remain politically engaged. They prompt me to mobilize and vote. They remind me to educate myself on pressing and important issues and support the best people to usher those issues into reality. Mr. Rogers encouraged us all to “Look for the helpers.” Let us do so, but with an extra step: look for the helpers, and then serve alongside them. Look to the helpers, for they are usually the site of a heightened and expansive political worldview, one that welcomes with open arms the voiceless, the powerless, and the disenfranchised. The news cycle is overwhelming, and sometimes it seems like the humane gains are few and far between. Like healing plants grown strong, hope is always there for those who have eyes to see it.

—Shayla Frandsen, author and political botanist

2. Thinking Wide and Deep

My wife and I have four great-grandchildren, and we want the earth to be livable when they are our age. Since 2011, I have advised the mayors, city councils, and employees of Provo, Utah, about the environment. It’s an appointed, ostensibly non-partisan volunteer position, but I have to thread my way through uncharted mine-fields of political beliefs to patiently encourage myself and city leaders to think more widely and deeply about how to improve our natural environment and climate. That means stretching to think more broadly about everybody in my fair city of Provo, the rich and poor, transient and semi-permanent, young and old, and to consider what other cities have done for their diverse residents. It also means stretching to think deeply through time, remembering our past and imagining our future: what do we want to keep doing and what are the long-run future costs of our policies? As psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman has pointed out, both wide and deep thinking are hard to do—we all tend to think that people close to us are all there is, and right now is all that matters. That is dangerous nonsense. Good thinking must be wide—it means going beyond what our neighbors, fellow church members, and social set believe. And it must be deep—it means remembering the lessons of history and doing the work of imagining a future that may be very different from our present. It seems to me that both are central to promoting the well-being of our communities and to sound political thought. May our thinking grow to become as wide and deep as required to keep the earth livable for our descendents.

—Donald K. Jarvis, environmental volunteer

3. In 2024, I Will Stay in the Fray

The past two general elections have left me weary. Lawn signage and social media posts highlight my neighbors’ extremes. I often respond and lean into my own extremes, doubling down on a position, ballot measure, or candidate. I grip my phone in a perpetual doom scroll, scanning my feed for content I know will fan the flame. And by the time that first November Wednesday rolls around and the ballots have been counted? I’m so weary. Disconnected. Distrustful. And there’s always another cause to fight for, another do-or-die moment.

Yet, what’s the alternative? I can’t in good conscience recuse myself from political discourse or staying abreast of current events. This country offers me many privileges based on my race, gender, and sexual identity—and isn’t that privilege a covenant call to advocate for the marginalized? So what do I do, the day after election day? I don’t feel peace or satisfaction. The tension in my jaw and the tightness around my heart don’t let up. When can I allow myself rest, and when am I obligated to answer the call to march? What is the balance between citizenry and complacency?

And yet, amid it all, I find buried amid this weariness a seedling of hope. What would happen if I refused to play the game? If I rejected the clickbait? If I threw away my team jersey and stepped into the demilitarized zone of political discourse? In 2024, I want to try.

I want to invite a full breath into my constricted lungs and step forward. Infuse humanity back into my neighbors and see them in their wholeness, choosing to love when everything on my screen says to hate.

The irony of social media politics is that at core, most of us want the same things: safe communities, robust education, the ability to thrive, a future for our children. The means by which we want to arrive at those ends varies from person to person, party to party, but at our center? We all want to be safe and loved. We want that connection and trust promised by Heavenly Parents who love all Their children.

In 2024, I will vote. I will research and advocate for the causes I find important. I will also choose you. I choose you over the algorithm, the fear-mongering, and the reductive smarmy pundits. I choose to see you as a person first, and a voter second.

As much as I wish I could fast-forward to 2025, beyond another general election cycle, I reluctantly accept that if I want to live out my discipleship more fully, I must stay in the fray, choosing you and me again and again and again.

—Charlotte Wilson, writer, editor, citizen

4. Practicing Dangerous Love

No matter how intense or intractable the polarization this year, we have the capacity to dangerously love our enemies.

Practicing dangerous love doesn’t mean we have to agree with people who hold different beliefs than ourselves. Or that we have to like their political or social beliefs. We can even actively be working or campaigning against their beliefs while still showing love and respect for them.

Dangerous love isn’t about conformity or giving in. It’s about caring enough about a person that their needs matter as much to me as my own and being committed to finding ways to get all of our needs met.

Politics is often considered a zero-sum game. It is about power and self-preservation. Dangerous love is about us-preservation.

We are in desperate need of dangerous love right now, in our homes, communities, nation, and in the world. To cultivate dangerous love, perhaps we may consider the following three principles:

A. Seeing people as people. This means striving to see the needs of others as equally valid as our own. Others are people we can empathize with and feel compassion toward—even when their political and social beliefs differ from my own.

While dangerous love doesn’t require that we enter into or stay in an abusive relationship, it does require us to see the humanity of and try to work with people that hold beliefs that are not our own.

B. Turning criticism inward first and curiosity outward second. This involves another inside-outside transformation. To solve difficult conflicts requires our looking inward and asking ourselves, “In what ways may I not be seeing these people correctly? What assumptions have I brought to this conflict?” Critical self-introspection provides an antidote to the blaming and dehumanization that often plagues conflicts.

When a family member shares a political or social belief that we find offensive, we can get curious about what lies underneath that belief. Why do they feel so strongly about that? What is in their life story that makes them believe what they do? What sort of fears or dreams do they have that aren’t being met? The question “why” is a magic one. The more we ask why, the more understanding we will have and the better we will be able to find a collaborative solution to our problems. The more understanding we have, the deeper our ability to find solutions that work for all of us.

C. Inviting collaborative problem-solving. When faced with conflict with another person, group, or party, commit to finding solutions that meet the needs of all of us.

Can we be both humble and committed? Determined but flexible? Dedicated to change while still showing respect for those that feel threatened by it? Patriotic while still being alive to pain that so many have felt and suffered at the hands of our country?

If we can’t do it with the people we came into this life with, how are we ever going to do it in our communities and in our country?

Politics is not about me or them. It’s about us, all of us.

—Chad Ford, educator and peacebuilder

5. My Vote is Now Sacred

Prior to 2020, I was politically disengaged. As a white woman with reasonable resources, I did not have to worry about politics as I did not see how politics affected me and, in my mind, I wasn’t in the right phase of life to engage. Between 2012 and 2020, I had five children at home and thus I excused myself from getting involved. This privilege allowed me to overlook the harm that came to others based on the outcome of elections and the policies that came after. I did not agree with statements made by the party I was registered to but I knew that voting was still expected of me. And so I voted, but no more. I don’t remember registering to vote or signing up for an absentee ballot but my mom, bless her, always had everything ready.

After moving to a new state, I didn’t recognize the ballot, so I voted in the races I felt I knew something about and I abstained on those I didn’t. Local elections were even more of a mystery to me at the time. I see this period of life more clearly now in retrospect: voting, and voting for just one’s own interests, is hardly political participation at all.

2020 changed all that. The pandemic, the public unrest over injustice, and the presidential election of 2020 was national news I just could not turn away from. I had school-age children and decisions made affected their well-being and the well-being of our surrounding community. My role in public life suddenly mattered, just as each of ours does now. Once I saw it, I couldn’t unsee it. Elections matter. Elections affect real people, families, children, and so many people that do not even have the right to vote. I now see my vote as sacred. My vote must do the most good for the most people. My vote must consider the effect on others.

I am a bit embarrassed by my past indifference. Thankfully, I have found resources, education, and organizations that not only help people reflect on how to know what they’re voting for, but how to become actively engaged in the process. I can say that I’m doing something every day, no matter how small. Roughly put, four years ago I became politically aware and angry. Three years ago I began finding my footing and advocacy work. The past two years have seen growth in pacing myself, learning how to have critical conversations peacefully, and teaching my five children about ethical government and our responsibilities as citizens. I savor local engagement the most now: I am working on when to speak up and how to do so in close relationships. Together, we can move the needle on democracy, ethical government, and caring for the common good by getting close, working local, growing curious, and engaging politically in the wellbeing of others.

—Stacie, a proudly engaged mother-citizen

Acknowledging the significance of participating politically (register to vote here) and engaging civically, Wayfare calls upon its readers in our ongoing series on “how to think politically,” to share and learn from the experience of contributors in preparation for more than 50 elections worldwide this year that will shape the future. Wayfare invites interested readers to submit their own contribution here. The series goal is not to tell the reader how to think but rather to extend resources and useful models toward enriching our individual privilege and responsibility to act politically.