In about a year, over fifty major elections will take place across the world, including a national contest in the US. We have all been recently invited and instructed to participate politically and engage civically. So how should one think politically? Despite the headline, this piece—a first chapter in an ongoing series of best political practices and principles to which any interested reader may submit their own contribution here—does not presume to tell the reader how to think politically. The reader alone enjoys that privilege and responsibility. Instead, Wayfare gathers here highlights from five individuals who describe how they personally think politically: first, Thomas Griffith, reflects on a civic politics that attends to the least of these as a means for at-one-ment; second, Katie Lewis considers under what conditions political disagreement leads to open minds and compassion; third, Karen McCandless offers a master class from her time on her city council; fourth, Heather Bennett Oman issues a cautionary tale of what happened when her father, Senator Bob Bennett, smiled at his political opponent; and finally, Benjamin Peters reflects on politics as the art of reconciling with loss—and donuts. Please enjoy, find inspiration, and share your own contributions for future chapters in building together a more abundant, sane, and just civil society.

Toward a Creative At-One-Ment

In trying to understand what inspired the New Testament authors, David Bentley Hart explains that they believed that in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, "nothing [could] stay as it was. All terms of human community and conduct [had] been altered at the deepest levels." According to N.T. Wright, the first century Christians believed that Christ's bodily resurrection inaugurated a new creation on this earth. As Christians, then, our work is to advance that new creation in all facets of life, including politics. Properly understood, the best work of politics creates community, and the work of creating community is the work of at-one-ment. A Christian politics works towards at-one-ment among people separated by social constructs, and has a special regard for those on the margins of society—those who Jesus called "the least of these"—who were, in his view, his "brethren." We can and should have vigorous debates among ourselves about how best to achieve such at-one-ment. Some will favor more government involvement than others. Disputants will strike different balances between liberty and equality, but all will agree those are the values we call upon to pursue societal at-one-ment. And in carrying on the debate about how best to achieve this at-one-ment, we see that experience confirms what scripture commands is true: contempt for one another is corrosive and divisive and prevents at-one-ment. Our arguments with one another must always reflect the truth with which C.S. Lewis concluded his greatest sermon: “Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbor is the holiest object presented to your senses.”

—Thomas Griffith, jurist

I Could Be Wrong

I took my first philosophy class during my junior year of college. Toward the beginning of the semester, the professor assigned a paper about one highly political topic. We were to research both sides of this topic and find out why each side believed the way they did. Wide-eyed and a bit shocked, having never considered any position besides my own, I dived in. By the end of writing that paper, I changed my major.

In philosophy classes, I learned that to make any argument well, I must discover doubt about my side. This doesn’t mean just knowing the weaknesses in my argument—it means an honest humility that I could be wrong and why I could be wrong. Instead of seeking the opinions that agree with mine, I searched for opposing opinions. Once I found evidence that refuted my argument, I was forced to let go of certainty. Then the questions arrived and my eyes moved wider. I learned to allow for several interpretations of any argument, knowing that my first interpretation of what they said or wrote was probably wrong: it was far too easy to distort or oversimplify their argument. Did I take their words out of context or misrepresent their intention? Was I overgeneralizing their argument—or overgeneralizing mine? Philosophy is not for those who want to attack a person instead of ideas. Philosophy is a practice of observation that requires careful reading, sound thought, and sincere questions.

Twenty-three years later, I attempt to practice this in real life. Sometimes someone makes their argument so passionately, it may feel impossible to disagree; but I find my eyes narrow when I hear only one side. When I ask good questions, reading news and posts from varying and multiple sources, alternatives pop into view. When I talk to people outside my normal social circle, outside my neighborhood, my state, my country, I’m empowered with more information. Inevitably, I face the knowledge that no matter how much research I do, no matter how careful my judgments, there’s always more to learn. The strength and certainty behind my arguments all blow away once the dust of my correct opinions settle, and I face my often-warped reality—complete with all my inherent bias. When I can let go of my need to be right, when I ask questions instead of proclaiming conclusions, I gain the skill to assume I could be wrong, and then—I learn compassion.

While many are disenchanted with politics, and many fear to speak up and add to the division, maybe politics is the opportunity to widen our eyes and broaden the embrace of our hearts. Learning both sides will likely feel uncomfortable. It might even feel wrong. But if it’s anything like writing my first philosophy paper, the new view will be well worth the effort.

—Katie Lewis, editor

What I Learned During Thirteen Years on the City Council

I seriously started learning how to think politically after a presentation I made with my community’s former mayor (FM). FM: “Karen, there is a vacancy on the city council and a woman needs to be there.” Me: “I will try to think of some women who would do a good job.” FM: “What about Karen?” Me: “Karen who?” FM: “Karen you. Think about it.” I went home and thought about it. I spoke with my family. There was fear, support, and excitement as I threw my name in the ring. At the time, I had no idea I would be selected, and elected three times and serve for a total of thirteen years.

I learned to think politically in the lively world of nonpartisan city government. Don’t let the term “nonpartisan” fool you: it can be very partisan. City government is where the rubber meets the road. This is where snow plowing, garbage pickup, water delivery, parks, police, and library decisions are made. How did I go about making decisions? Here are some steps I tried to follow then and now:

A. Examine options. When deliberating on a matter, what are the options out there? Do I agree or disagree with the changes, or do I not know enough to decide? I learn to examine details.

B. Get frustrated but not angry. Anger can be a very dangerous emotion. Nonetheless I grow frustrated, and sometimes with good reason. On the city council I sometimes found myself frustrated with the political views of someone I was working with, after I had confirmed my understanding. These days I can find myself frustrated as I try to understand why someone would believe information the facts don’t support. Feeling frustration, I have learned, is appropriate. I try to observe it in myself and others at a respectful distance. Politics is supposed to be hard. Then I turn to step D.

C. Get to know people. We are all human beings and children of God and should be treated as such, no matter what. I strive to treat others with respect and compassion. As an official, I tried to answer emails within twenty-four hours of receipt. As an introvert, phone calls took a bit longer. :)

D. Communicate. If I don’t understand something, I try to ask. Sometimes diagrams help me, other times hearing it over and over helps. If I cannot explain the concept to someone, that means I don’t know it well enough. Back I come to learn more.

E. Have an open mind and be willing to change. I was elected to do the best I could with the information I had. Sometimes the results of a decision turned out in a way nobody imagined. Or the feared consequence didn’t happen. Now and then, I remain willing to learn more and reconsider, when appropriate; at other times, I know that, even as I continue to learn, my decision needs to not waver. The difference, for me, usually came down to a judgment of how best to serve the most needs the best.

The final life experience that formed how I think politically was my husband’s sudden death. My “what matters most” list changed in ways I never imagined. In the eleven years since his passing, I continue to hone my list.

My city council tenure ended nearly ten years ago, and I have incorporated those six steps into my day-to-day life. They continue to serve me well.

—Karen McCandless, neighbor

The Art of Smiling with the Opponent

On January 20, 2009, the day Barack Obama became president, my father—Bob Bennett—stood side by side with him on the inaugural dais. As the ranking Republican Senator of the Rules Committee, my dad was given special inaugural duties. I’m still not sure why that is, but it meant that on that frigid historical day, Dad witnessed the first black president sworn in just a few feet in front of him.

The presidential inauguration is the ultimate day of bipartisanship. It’s the day the country honors the most American thing of all, the peaceful transfer of power to a new leader elected by the people. It’s a day of celebration. The American experiment continues: huzzah!

Some official photographer snapped a picture of my dad that day, standing near Obama and smiling.

The next year, my father was fighting for (and losing) his political career. The LA Times published the Obama photo with the story about Bennett's unpopularity. I saw an interview with one of my father’s constituents, describing his rage at seeing that photo. Why was Bob Bennett, the voter railed, so happy? What did he have to smile about? Was there something he wasn’t telling the people of Utah? Was the Republican senator actually pleased to have a Democratic President? Bennett should have been yelling, or scowling, or fighting, not smiling. The message was clear: common courtesy and social convention have no place in the political arena. It is a sin to smile at a Democrat.

Politics, by design, is tribal. These “ites'' versus those “ites.” People adopt beliefs about things they really don’t know much about because their tribe has adopted that belief. It’s not possible to know something about everything, so it’s natural that people go along with what their tribe does and says. The problem in politics, though, is that to protect the tribe, the opposing tribe has to resemble an ignorant and sinister conspiracy of cartoon villains. And villains do not deserve courtesy, handshakes, or a smile. They deserve ridicule, mocking, and hate (see Twitter).

I often wondered how my father kept his soul in politics. He used to say the only way to be a good politician was to not be afraid to lose your job. He also refused to reduce people to caricatures or agendas. His fellow senators were not his enemies. They were decent men and women serving their country. He also genuinely enjoyed the puzzle of legislation. It’s difficult to pass good laws. My father knew it should be a group effort. (He also died without ever posting a single tweet.)

No one, not even a genuinely undesirable candidate, is a cartoon villain. Most people are just ordinary folks who want their country to be safe and prosperous. We can disagree on how to get there and we can fight to make our points. But it’s okay to smile with the opponent as we do.

—Heather Bennett Oman, speech therapist

Politics is the Art of Doing Good with Loss—and Donuts.

My middle school cafeteria taught me something about voting with dignity, and donuts: Politics is the art of doing good with loss. Those who play poorly, or not at all, may lose the most.

I grew up attending neighborhood caucuses in my middle school cafeteria in Iowa. Neighbors would listen to one another over donuts, bid for votes, and then sort themselves into different candidate corners. (Donuts have the virtue of filling mouths and opening ears.) This hard, humbling work meant everyone lost something in that cafeteria: most left feeling like they had gained by losing, or weakening, or changing some prior opinion or conviction, while those who refused to learn or listen lost the respect of their neighbors. How can we make the most of loss?

Which one is the greater corruption of politics: the false belief that since all politics is corrupt, I should not vote at all, or the false belief that since my party ideology is better, I should vote with ideological certainty? The first idol corrupts democracy; the second idol corrupts the purpose of parties. Until there is ballot reform, I must vote against the worst candidate with hesitation and evidence, not with ideological conviction and monstrous fears. Checking myself with evidence and reconciling with appropriate loss (like taxes and mortality) might even save our country. The best religious institutions declare their neutrality and command each of their members to participate politically, meaning each of us must take calm, thoughtful responsibility for our own civic action and votes. So, given two major political parties, I vote selectively down the ballot (like dishes in a cafeteria buffet) to get rid of the worst candidate in each competition, knowing full well that who I vote for today may become the worst candidate tomorrow.

All votes require reconciling with loss, for politics requires learning, weighing, and voting for the best balance of public needs and goods. Choosing between policies requires sorting through conflicting values, so, acknowledging the debt I owe to my parents, I seek to set aside what I heard over the dinner table growing up, discount all campaign talk about the future (both promises and threats), and focus on learning about those policies that empirically have done or are doing the best for the public interest. Again, this means discounting monstrous fears and focusing on the evidence, which in turn requires reading, not watching, the news I pay for, familiarizing myself with basic policy research using public sources, and standing gracefully in my own informed uncertainty.

So while our thinking may be complex, the act of voting remains painfully simple: it collapses the complex and colorful garden of our real world into a ballot of either-or choices (thanks Madison!). If we don’t like this, seek ballot system reform. Until then, think through each voting choice, prioritizing candidates in terms of which one will provide the greatest benefit to the greatest needs. Then vote against the worst and get out the vote.

The middle school cafeteria awaits—this time with dignity and donuts.

—Benjamin Peters, teacher

This is the first installment in the Wayfare series How to Think Politically. The second installment is here. If you are interested in submitting your own reflections for consideration toward future installments, please review and submit through this form here.

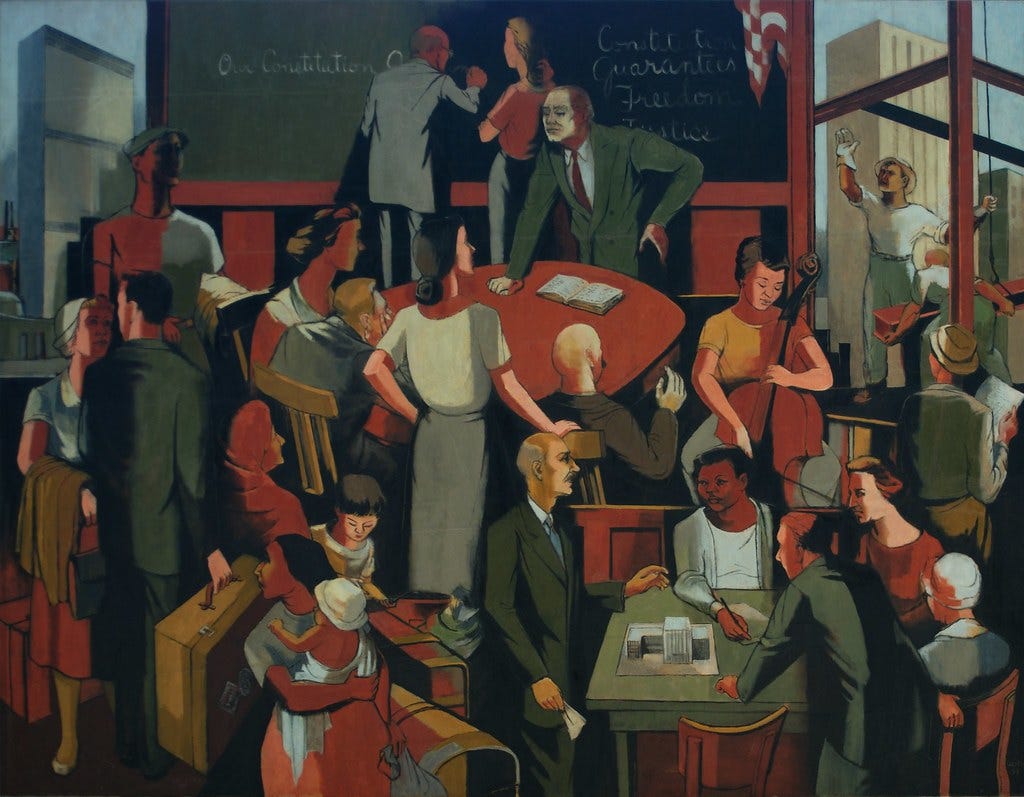

All artwork is from the Harlem Renaissance.

DON’T MISS THESE…

Check out the latest Faith Matters podcast episode, an interview with McKay Coppins (see more info below).

NEWS

Atlantic reporter McKay Coppins’ new biography of Mitt Romney has climbed to the #3 New York Times Bestseller slot. Drawing on almost unprecedented interview, journal, and email access, Romney: A Reckoning traces the political career of the man who, though once the face of the Republican party, now stands as its preeminent pariah.

Congratulations to biblical scholar, TikTok influencer, and Latter-day Saint Daniel O. McClellan, who recently received the 2023 Richards Award for Public Scholarship from the Society for Biblical Literature for his “demonstrated excellence in public scholarship.”

Be sure to check out Farina King’s excellent new release, Diné dóó Gáamalii: Navajo Latter-day Saint Experiences in the Twentieth Century, published through the University Press of Kansas. In this deeply personal collective biography, she provides a history of twentieth-century Navajos who have converted and joined the Latter-day Saint tradition. Hers is a fascinating exploration of the entanglement of religious and indigenous identity within settler colonial institutional structures.

The Center for Latter-day Saint Arts has issued a call for proposals for the 2024 Ariel Bybee Endowment prize. “[E]stablished in 2021 to honor the legacy of Ariel Bybee and to foster the creation of new works by Latter-day Saint artists in disciplines that correspond to her varied career and interests in music and related arts,” this year’s endowment prioritizes submissions which addresses the needs of youth music education. More information can be found here.

Wayfare expresses its deepest condolences at the recent passing of M. Russell Ballard, President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. A dedicated servant of Christ, Ballard drew upon his personal heritage as a descendent of Hyrum Smith in continuing to usher forth the Restoration. Our thoughts and prayers go out to his loved ones at this time. Remembrances of his life can be found here, here, and here.

It is indeed wise of us to search for at-one-ness in public life, to realize that making arguments with others is a perennial necessity, to listen attentively and to smile good naturedly, and to be good losers. Our communities depend on our willingness to engage with one another about what matters most, while expecting concurring and dissenting in parts to be the norm.