This is the sixth essay in the “Covenant Life” series, where we are exploring together why covenants matter and just what they mean and do. Please see previous essays: Rising Together, My Side-by-Side God, Uphill on the Yellow Brick Road, Toward a Practical Theology of Sealing, and Homeless Jesus.

The conception of faith that glommed onto me as a child was that of propositional faith. Each time I found myself seated in a cushioned chair for a bishop’s interview and was asked whether I had faith in Christ, the question registered as: “Do you believe the Church’s truth claims about Jesus Christ—that he is the Son of God, that he performed the Atonement, and that he is the way to salvation?” Conversely, each time I overheard hushed conversations about family or ward members who had “lost their faith,” the implicated individuals had somehow misplaced their conviction in certain key spiritual truths.

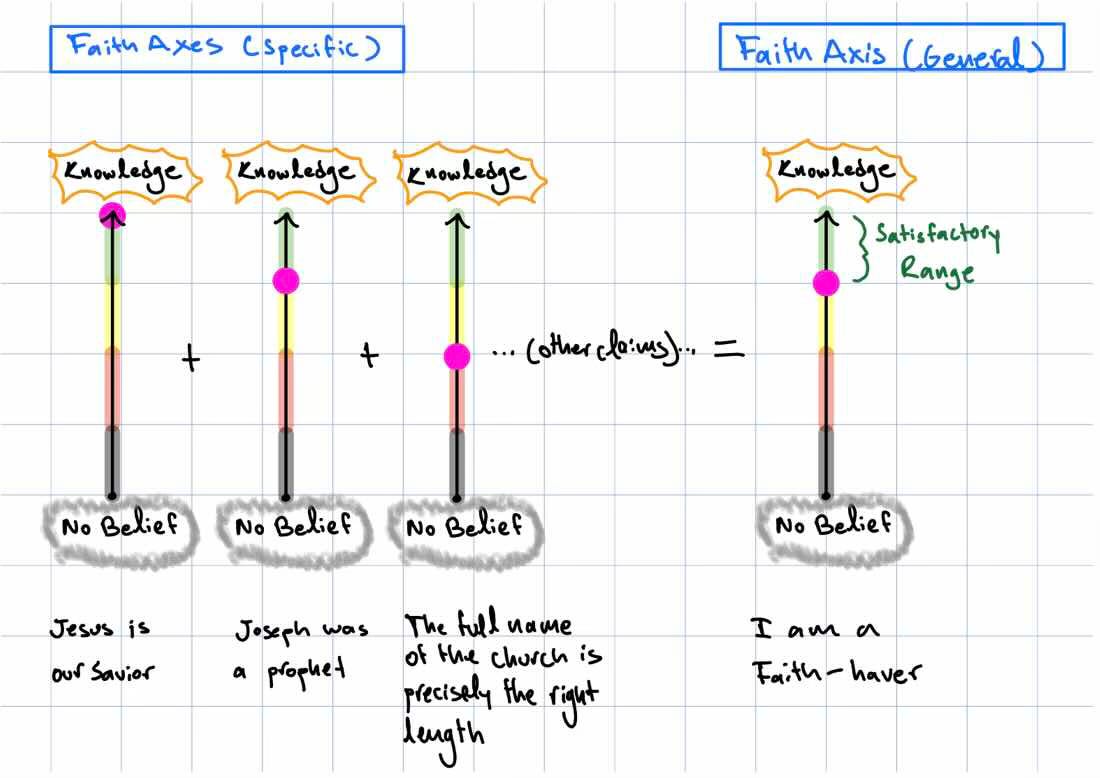

For any given spiritual claim, it seemed there was an imaginary faith axis ranging from no belief all the way to belief’s perfect form—knowledge. Each position along the axis had associated rewards, with the cavernous darkness of no belief on the low end and the blinding ecstasy of knowledge on the high end. To “have faith” in a specific claim was to occupy some satisfactory position along its axis. To “have faith” generally was to occupy satisfactory positions along the axes of all the spiritual claims that really mattered.

Figure 1

What we believe is significant, and so, while acknowledging other worthy definitions of faith, I have not rejected this inheritance. I still experience faith primarily as propositional.

For many years, I intuited that faith was the foundation of a spiritual life. Without faith, there was only the cavernous darkness at the sad end of the axis. Because I preferred the associated benefits of faith-having (particularly the assurance that comes with belief in an eternal family), I kept a very tight grip on my faith. It was a wake-up-at-6-AM-to-use-a-third-party-but-definitely-Deseret-Book-approved-New-Testament-DVD-study-guide-before-piano-practice-before-school-at-the-age-of-nine kind of grip. It was critically important to me that I be ever moving away from the insecurity of faithlessness and toward the security of knowledge—and I was confident that if I read the scriptures, prayed, went to church, and took things seriously unlike my lax Valiant 10 peers, I would enjoy a life of monotonically increasing faith.

Diligent scripturesprayerchurch and manifesting faith-go-up worked for a while. I could almost see my future as a silver-haired apostle whose only problem was the medical inconvenience of a thoroughly burned-out bosom. However, it eventually became evident that my faith was not monotonically increasing—nor was it nearly as much under my control as I had supposed. Sometimes, despite overloading on all the prescribed faith-building inputs, I simply could not make faith go up. Other times, despite spending months away from the scriptures due to the dreaded scripture ick,1 I was gifted faith in moments of need. Often, my faith seemed to covary more with caloric intake than it did with spiritual work.

Eventually, I became comfortable with the idea that how much we believe spiritual claims can naturally fluctuate with mental health, environmental factors, and time since lunch. We do not fully control these things, and so we do not fully control our faith. This admission seemingly put my spiritual life on shaky ground.

One night this spring, I was walking back to my apartment, lost in thought. The physical world, with its pollen-flinging trees, parallel-parked cars, and distant streetlights, faded away. I miraculously glided over the sidewalk crack that normally sent me jolting forward. In this trance, my meandering mind turned to spiritual matters. Eventually, it stumbled upon two seemingly discordant realities.

First, it occurred to me that if I had been pressed at the moment, I might have struck out on the first three temple recommend interview questions. For each of those key propositions, I felt neither belief nor disbelief—just uncertainty. Second, I was not experiencing a cavernous darkness at all. On the contrary, I was feeling a burning desire to live the Sermon on the Mount. I would have dumped all ten of my possessions into the Bishop’s Storehouse. There, frozen in front of my neighbor’s creaking gate, the foundation of my spiritual life was nowhere to be found. And yet my spiritual life was richer than ever.

I marveled.

Perhaps bottoming out on faith that night was simply a natural fluctuation (although I had been well fed). But, given that I had simultaneously experienced a longing to know and live the divine, I came to suspect godly trickery.

Faith is a spiritual gift (1 Cor. 12:9), and spiritual gifts are, somewhat notoriously, gifted. Their bestowal is subject to divine plans. When Joseph Smith was given the gift to translate the Book of Mormon, he was told to “pretend to no other gift” until God’s purpose was fulfilled (D&C 5:4). He was denied access to other desirable spiritual gifts for a season and commanded to prioritize the spiritual work God intended for him at that time. Maybe my moment of ostensible paradox was pointing me to another spiritual vineyard. The fact that a period of faithlessness could be accompanied by a glowing spiritual yearning rather than a cavernous darkness gave me the confidence to not pretend to the gift of propositional faith. Perhaps I was being shielded from the anxiety of trying to control my faith and being steered towards the beauty of what I have come to call covenant longing—a foundation for a rich spiritual life that is robust to the vagaries of faith.

To grow up in the LDS church is to grow up in a sea of spiritual truth claims. Our worship is full of discussing, studying, and proclaiming truths. Expressing acceptance of these truth claims grants us formal access to our most sacred rituals and informal passage into our communities. Embedded in this milieu, it is easy to zero in on the axis of faith—to fixate on propositional faith as the foundation of our spiritual lives.

The benefits of propositional faith are significant. Depending on the claims we believe, faith can provide existential peace and motivate us to become better people. However, the risks of hyperfixating on propositional faith, of treating it as the foundation of one’s spiritual life, are also significant. If faith runs out—whether due to lack of spiritual effort, biological noise, or divine purposes—the game is over. Our spiritual life is unfounded, and staying engaged with our truth-saturated church becomes difficult without feeling disingenuous. We can lose faith, spirituality, and community in one fell swoop.

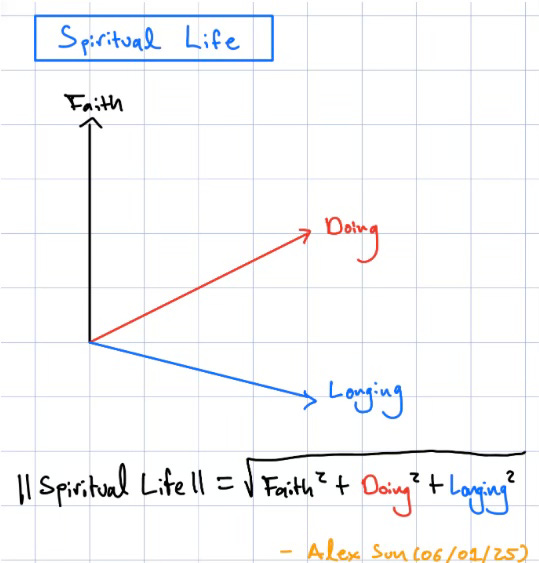

Thankfully, spiritual lives are not one-dimensional. After processing my experience with the help of wise friends, I have come to see my spiritual life more like this:

Figure 2

The axis of “doing” is almost impossible to miss as a church member. By any measure, Jesus is a pretty big proponent of doing good. The author of James won’t even acknowledge your faith if you aren’t doing something about it. And the restoration tradition is obsessed with building communities that behave in Zion-like ways—something that requires a whole lot of doing. “Doing” is necessary for a meaningful spiritual life.

The axis of “longing” is perhaps the easiest to come by. People naturally long to know and live the divine. We intuitively seek higher powers and higher principles. We desire perfect relationality. Because these longings are so natural, either mysteriously gifted to us or picked up as we taste goodness along the way, they are persistent, even in the absence of propositional faith. They persist when we are uncertain whether the object of our desire exists at all. Jesus wants me to live with my family forever, and so do I—even when I am uncertain that families exist eternally. Jesus wants me for a sunbeam, and gosh-dang it, so do I—whether I believe it is possible for me to be a sunbeam or not.

Our spiritual longings are beautiful. They shape souls. They inspire wonder and awe. They have intrinsic value. They are ends to an end.

At the same time, longing can animate the rest of a spiritual life. With longing, “doing” does not necessarily stop or lose its meaning when propositional faith is missing. One can long to build Zion even while utterly uncertain that Zion is possible, and building Zion despite this uncertainty still brings joy. With longing, propositional faith can be reignited a la Alma 32. And if the seed thing is taking too long, there is always the tried and sometimes true tactic of faith smoothing. You’ve had faith before, and you anticipate having faith in the future—because you want faith. Just dip into that imaginary future faith now, and you might make it through to the other side. Longing can keep the spiritual lights on through storms of uncertainty and listlessness.

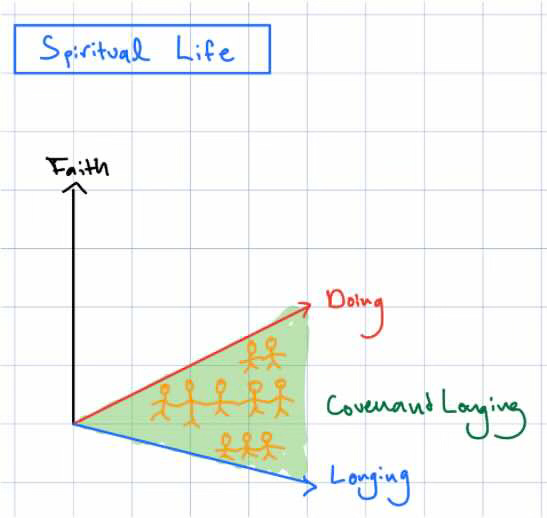

Yet, it wasn’t longing alone or even longing + doing that sustained my spiritual life during my most recent faith turbulence. It was covenant longing.

LDS covenants, at their core, are shared longings. We long to be woven into loving community, bound with compassion and empathy. We long to trust others enough to let them see our wounds; we long to be trusted enough to be shown the wounds of others. And so we make and renew the baptismal covenant (Mosiah 18:8–11). We long for right action, actions in line with the principles that we hope govern the universe. We long for guardrails to protect us from mindless hedonic gradient descent that robs us of deeper joy. And so we covenant obedience. We long for a world where we have all in common. We long for the end of transactional relationships. And so we covenant to live the law of consecration. Each covenant captures a communal longing and makes both the longing and the community more concrete. When we covenant, we are not hoping “for things which are not seen, which are true” (Alma 32:21). We are longing for things that are not real, which could be, and committing to work alongside every sister and brother to make our longings real in the world.

Figure 3

When we are active in our covenants and attend to our longings, we are engaged in covenant longing. Covenant longing can sustain a vibrant spiritual life in the face of fluctuations in faith, natural or otherwise, and fill the dreaded cavernous darkness of faithlessness with light and spiritual purpose.

Immediately before my walk home that night, I had been in another apartment, not a quarter mile away. Eight or so friends from my ward had gathered for the evening to eat fresh bread with homemade butter that had been molded into the shape of penguins. More importantly, we had gathered, as we had done every two weeks for the last two years, to support each other in our spiritual journeys—to think, feel, and process together. Together, we longed for Zion—and Zion existed that night.

Over the next two weeks, little changed faithwise. But I still wanted to do some Jesus-y things, so I attempted some Jesus-y things. It felt good. I wanted to be at church, so I went to church—and felt no discomfort, no need to separate myself from the propositional-faith-havers. Two weeks after my faithless walk, my friends gathered again. I had a newfound awareness of an acute longing. An acute longing that everyone could have what I had been blessed with: covenant friends joined in covenant longing, eating warm bread and penguin butter.

August Burton is a first-year medical student. He enjoys learning words that start with “p,” cooking at a snail’s pace, and writing on recycled legal pads.

Art by Bryan Mark Taylor.

The scripture ick is a close cousin of the egg ick. It occurs spontaneously after a period of prolonged exposure to the scriptures and manifests as feeling micro-aggressed within the first three verses, resulting in closing the book before more damage is done.

Excellent perspective on covenants that reflects real and relatable experience and a kind of faith that rings true. Longing is related to having faithful desires, which, perhaps, may be as important as faithful actions. Actions can become rote or transactional but not so much longing. Kudos!