How many more fairy stories could we read? How many more metaphors are there? Is Atonement incarnation? An infusion of light? Is it mercy or moral influence? Is the Atonement joy? Grace? School? Eternal progression?

We have looked at six stories here but could read many more. Just as the Savior taught in different ways—sometimes answering questions directly, sometimes answering questions with questions, at other times offering parables, or even not speaking but answering with actions or examples—the Atonement is multifaceted. It works in different ways for different people as it responds to their needs.

The Atonement is infinite, and it can be experienced and understood in infinite ways.

Because of this diversity, these metaphors are abundant and easy to see. We talk about the Atonement like it is a great mystery, and there is some truth to that, but at other times it seems that it is so comprehensible that we can’t help but recognize it in every moment of our lives. When we plant a garden and invite our friends and family to enjoy it, we see our work as similar to Christ’s. When we make a new friend or help someone in need, we recognize the connections between what we are doing and what he has done for us. When we fly a plane, buy our child a bicycle, remodel a house, heal after a long sickness, even not heal after a long sickness, we see in those tasks and activities shadows of Christ’s divine mission.

When I look for metaphors of Christ (symbols, similes, types, analogies, call them what you will), I find that they are everywhere. And we have seen how fairy tales can help us understand these metaphors. Some of the fairy tales are simple, like “Snow White,” which features a princess who bites an apple, dies, and then is resurrected by the kiss of a prince. Others feel unintentionally meaningful, like “Tam Lin” or “Beauty and the Beast,” which seem like they are shared for entertainment but reveal gospel truths when seen through the right lens. Yet others are intentionally metaphorical, like “The Selfish Giant,” which contains Christ as a character.

I hope that in reading these fairy stories and exploring the ways we often conceptualize salvation, you have come to understand the Atonement better. But there will always be more to learn.

Atonement as Eucatastrophe

So, here, in the conclusion of this series, we will look briefly at one more metaphor, one that is dear to my heart. To introduce it, we will go back to Tolkien’s “On Fairy-stories,” where, at the tail end of the lecture, he writes this:

The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels . . . and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable Eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; . . . The Birth of Christ is the Eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the Eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. (35)

Here, instead of looking at various conceptual metaphors that can be found in fairy stories to see what they can teach us about Atonement (which was my project), Tolkien instructs us to look at the Atonement itself as a true fairy story.

This isn’t a new idea. Many scholars and theologians have called the gospel a fairy story. As recently as 2010, President Dieter F. Uchtdorf said in a talk to the young women of the church, “‘Happily ever after’ is not something found only in fairy tales. You can have it! It is available for you!”

In his talk, Uchtdorf discusses “Beauty and the Beast,” “Rumplestiltskin,” and “Cinderella,” explaining the similarities between these stories and our lives. He looks at how we, and the fairy tale characters, go through trials and adversity before finding Eucatastrophe (my word, not his). Then he bears witness that the gospel is the way to find that happy ending, that through Jesus Christ we can get there.

In his book Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy and Fairy Tale, author and preacher Frederich Buechner also writes about the gospel as a true fairy tale. He expands on the idea with gusto, adding his own poetic flair. “That is the Gospel,” he writes,

the meeting of darkness and light and the final victory of light. That is the fairy tale of the Gospel with, of course, the one crucial difference from all other fairy tales, which is that the claim made for it is that it is true, that it not only happened once upon a time but has kept on happening ever since and is happening still. To preach the Gospel in its original power and mystery is to claim . . . that once upon a time is this time, now, and here is the dark wood that the light gleams at the heart of like a jewel, and the ones who are to live happily ever after are . . . all who labor and are heavy laden, the poor naked wretches wheresoever they be. (90–91)

The Gospel is the good news that Christ has overcome the darkness of the forest. He has defeated evil, sin, and death. This good news can be discussed and analyzed metaphorically in potentially infinite ways, but every metaphor we use or could use means that we can have a happy ending, not just in our imaginations or in a fictitious world, but in reality. So maybe the best metaphor for all that Christ has done for us, is the “happy ending” itself, the good catastrophe, the surprising and inevitable conclusion to the fairy story that is our lives.

This Eucatastrophe plays out in the lives of saints the world over in varied and remarkable ways. Many people meet Christ as they repent of their sins. They find in him forgiveness and justification. Some come to him wounded or sick; they meet him as a healer who has the requisite power not only to make them whole but also to understand and succor them through the entire healing process. Others meet Christ in moments of grief or sorrow and find his improbable comfort and peace. Just as President Uchtdorf testified, we all have to go through challenges, but with the blessing of the gospel, we will find ourselves emerging on the other side of them with joy and hope.

Eucatastrophe in My Life

In my life, I am often surprised by the ways my Savior reaches me. It is easy to look at Christ in the scriptures, see his sinlessness, and imagine that he could never understand what it feels like to feel sin and regret, but my experience is that he does in a very fundamental way. I had trouble understanding how Christ could support me through the experiences I have had as a woman and a mother—after all, he is a man. What could he know about childbirth and nursing, about raising children, or even having a monthly cycle? But the more I seek his closeness through these experiences and search for him in my moments of sin, sadness, or confusion, the more I find him there, willing and able to offer comfort, understanding, and assistance. He offers clarity of thought. He offers peace when faced with anxiety, turmoil, and contention.

One way that Christ has reached out to me had little to do with sin, woundedness, or death and everything to do with loneliness and despair. When I graduated from high school, I left my family to enter the dark forest of college. My four closest high school friends went to BYU in Provo, but I didn’t even apply. Having grown up just ten minutes from BYU campus, I wasn’t interested in more of the same. I wanted to go far away to school and have an adventure in a strange land.

I ended up only a few valleys north at Weber State University in Ogden, but even though I could drive home in a little over an hour, it felt like I was far, far away. It was completely new and foreign. I had three roommates who were strangers to me. They were strangers because I didn’t know them, and they were strangers because as I got to know them, we found no similarities between us. We didn’t have the same beliefs or worldviews. We didn’t eat the same things, or do the same things, or even study the same things. I didn’t know anybody. I felt like Snow White, alone in her sleep, the only one lying under a coffin of glass. Or like The Beast, who was alone in his curse, not having another beast like him in the world.

I tried to make friends in my classes and at my work. And now, when I look back, I realize that I could have made friends if I had known how, but I didn’t know how to connect with the people around me. I was afraid of people who were different from me and afraid of changing myself.

When I look again at these fairy tales through the lens of loneliness, I see that each of the protagonists of the story is lonely in their own way. Laura, who has Lizzie and other people around her, is alone in her addiction and illness. She is trapped in her memories, craving something those around her have never tasted. The Selfish Giant is alone in his home and garden; he feels no connection to anyone, no love for them, just icy winter in his cold, lonely heart. Tam Lin occupies a liminal space unique only to him. A wild shade, he lives among the fae but is not one of them; he is human but is not a part of human society.

When we—like Tam Lin and the Beast, like Laura, Snow, and even the people and princess in “The Most Remarkable Thing”—are going through trials, it is easy to feel alone in them. I certainly felt alone in my first year of college. I was sure that nobody else was experiencing what I was going through, not my friends who went to college together; not the other students I studied with, who all seemed to have friends and family around; not even my parents, who loved and supported me, but who hadn’t graduated from college and (I thought) couldn’t possibly understand what I was going through.

So, where did I find my support? I found it through Christ. In my first semester of classes, I had a hard time attending church for all the reasons mentioned here. I went home a lot on the weekends to visit my family. When I did stay on campus, I didn’t want to go because I didn’t know anyone, and it was awkward. I had so little money that I wasn’t doing a good job paying my tithing, and I felt ashamed. But one day, during the week, I was crying alone in my tiny dorm room that only had enough room for a tall bed with a dresser underneath it and a tiny desk and bookshelf against the far wall, and I decided to pray. It was a prayer of loneliness, a prayer of desperation. I needed companionship and love, and something more, maybe strength to go on, maybe hope that things would get better, that I wouldn’t feel so alone. As I prayed, I felt all of those things. I felt a blanket of love enveloping me. I didn’t hear a voice, but I felt a voice say that I wasn’t alone, that I was loved and understood. I felt a good catastrophe, a connection with my Savior. I was being healed and reconciled, strengthened, protected, and even justified all at once. I was feeling hope.

It was a beautiful experience, and it helped me not to give up, to keep attending classes, searching for friends, going to church and clubs, and working. It was a real moment of Eucatastrophe for me.

I have had other experiences of Eucatastrophe in different times and different ways. I have felt the support of Christ in moments of crisis as strengthening and calming, or as a peaceful sense of acceptance or resistance. I have felt it as forgiveness, but also as healing. I have felt it as intelligence scooped into my brain like you scoop and dump a cup of flour into a bowl of batter. I have felt it again and again as love that won’t let go.

Every Metaphor is Right

I have been able to understand my own experiences better after reading these fairy tales and thinking about some of the ways the Atonement can feel, some of the miracles it can make. These stories have also helped me understand the experiences of others when they share them with me.

I still don’t know how it works. I don’t know how Christ has the power and capacity to make Eucatastrophe for all of us. But I know how it feels to receive it. C.S. Lewis writes in Mere Christianity:

The central Christian belief is that Christ’s death has somehow put us right with God and given us a fresh start. Theories as to how it did this are another matter. A good many different theories have been held as to how it works; what all Christians are agreed on is that it does work. (54)

This is what I know: that somehow, someway, Christ can bring about a happy ending for all of us. Debates about whether he does this through justification, radical healing, or reconciliation seem moot at this point. Because yes, he does all of those things. He does justify us and reconcile us and cause us to be reborn, but he also does more. Each of those metaphors represents a small part of what he does. As I lay crying alone in my bed at eighteen, I needed companionship, and he provided that too. He forgives and reconciles, but he also comforts and brings peace. He teaches and enlightens our minds. He sanctifies us.

The Atonement is bigger than the law. It is bigger than healing. It is bigger than your piano lessons or your brother saving you from certain death as he holds on to you at the top of a cliff. It is bigger than bread, water, or wine. It is bigger than a father welcoming you home after you have wasted your inheritance (Luke 15: 11–32) and bigger than your mother, who carried you, birthed you, and fed you from her own body before she supported you through the rest of your life. It is bigger than any of us. Bigger than Aslan, bigger than Gandalf, and bigger than any of the heroes we have read about in these or any fairy tales. It is the biggest thing, the most incredible thing. It is the only way, the capital-T truth. It is life.

Prophets have tried to describe it. They use a lot of superlatives, calling the life of Christ the greatest story ever told. Christ is called “Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6), “For the Lord your God is God of gods, and Lord of lords, a great God, a mighty, and a terrible” (Deuteronomy 10:17). He is not only god, but the God of gods. Not only king, but the greatest king of all—the King of kings. Always supernal, the greatest of the great, infinite and eternal, the first and the last.

One of my favorite scriptures is First Corinthians chapter two, verse nine, where Paul writes, “Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him.” Both metaphor and superlative descriptions fail at capturing the Atonement because we don’t have the room in our hearts to understand it, but I think there is a reason that stories are the best tool we have for understanding.

Stories Teach Empathy

A good friend of mine taught me that understanding comes from the combination of knowledge and experience. Sometimes, when we search for understanding, we start with our experience and try to work outward from ourselves, seeking ways to frame and understand the things that have happened to us. This would be like having an experience with Christ and then pondering on it or writing it in a journal. At other times, we work from the outside in, not seeking to understand our own experiences but instead hearing about, studying, or learning from the experiences of others. This is empathy. Listening to stories, either personal or fictional, can give us understanding without experience, almost like a map made by someone who has been where we haven’t been ourselves. This sort of outside-in learning can be a huge time saver. It can also open up our perception of our own experience, giving us language to understand ourselves and those around us.

Christ lived a sinless life. He lived in one time and one place, but he had perfect empathy and understanding. He knows all of us—not because he is us, but because he knows us—he has empathy for us. He has knowledge. Stories and scriptures can help us gain that knowledge. Stories teach us how to understand our own lives and the lives of others. They teach us how to develop the empathy to assist, support, heal, and succor those around us. This empathy can be added to our faith and trust to make a more perfect understanding.

As we read these stories and ponder these metaphors, we are also coming to understand our Savior and his mission better. We are learning to empathize, not only with each other, but with him. We are staying awake, turning our focus to Jesus Christ, and his work, watching with him “one hour” (Matthew 26:40), and doing our small part to witness his holy work and support him in his trials.

Christ has made a happy ending for each of us. Eucatastrophe teaches us about Atonement because every happy ending of a fairy story helps us remember what we already know, that in the end, good triumphs over evil. But Atonement is also Eucatastrophe because every time we read a story to the end and find that moment of victory or miracle of salvation, we learn new ways that Christ succors us—whether it is through love or trust, through healing or rescue, through hope, reconciliation, or learning.

I wish I could say that studying these metaphors has given me a complete picture of the Atonement in all of its detail. But how could it? How could I even find room enough in my mind and heart to receive the Atonement in full? It’s okay if right now, I only have a teaspoon of understanding, a morsel of faith. I have watched with my Savior for an hour, and I have gained some new tools, expanded my understanding. I hope, here at the end, that you, like me, feel edified, and that you are ready to go forth and continue in learning, by story and by faith.

Chanel Earl is a writer—mostly of fiction—who currently teaches writing at Brigham Young University.

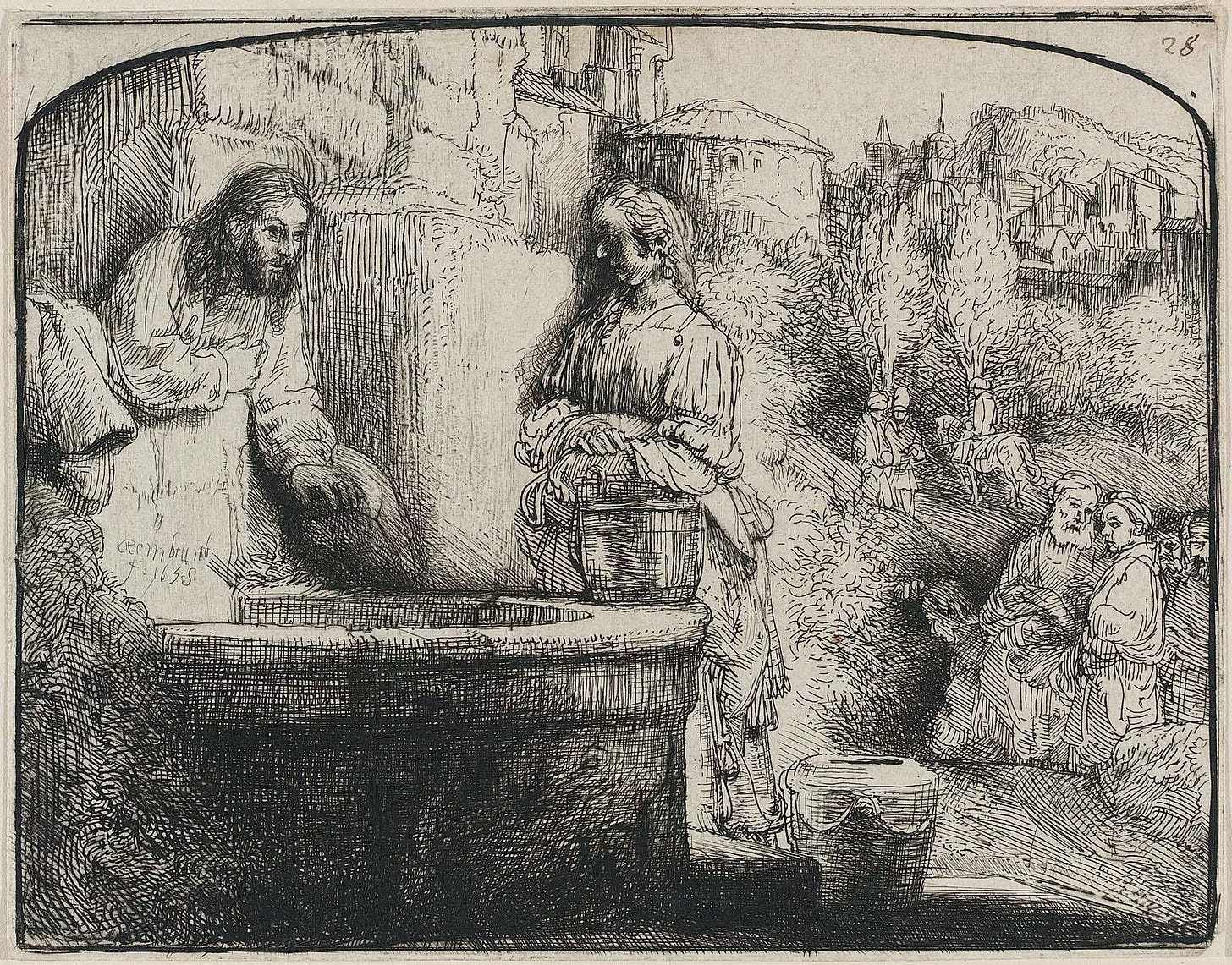

Art by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)