Click on the link above to read “The Selfish Giant” by British writer Oscar Wilde (1854-1900).

More than in the previous metaphors, where sin and redemption were represented by physical losses and gains, “The Selfish Giant” offers us a complex internal landscape to contemplate, even as we hold on to the fairy tale setting.

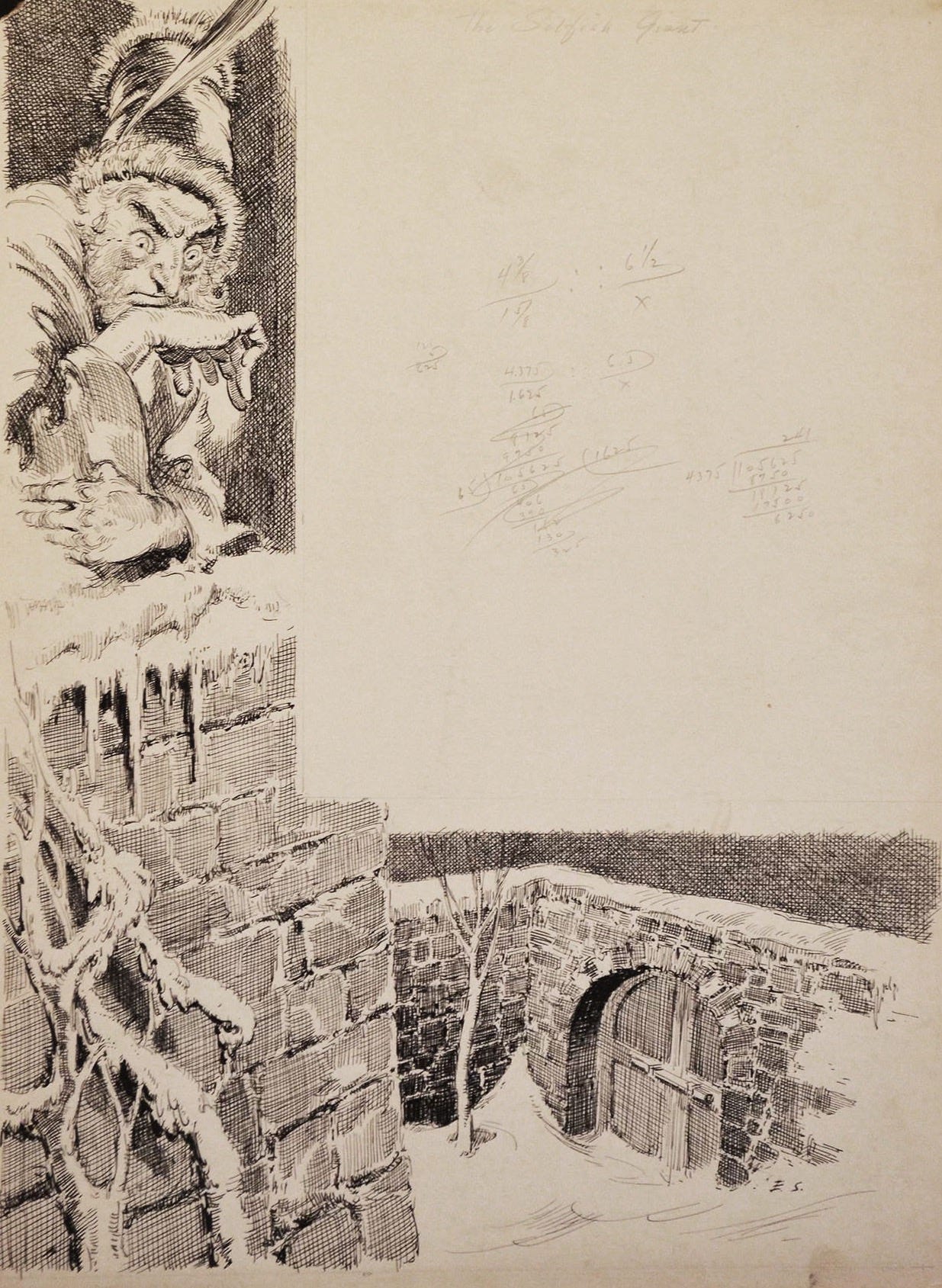

“The Selfish Giant” is a beautiful illustration of both estrangement and reconciliation. As in many fairy stories, we again have a garden, but this time, our protagonist doesn’t eat the forbidden fruit but instead keeps the fruit locked up for himself.

I have no trouble relating to this Giant. Nominally, his sin is selfishness, and his greatest offense is building a wall to keep others out of his garden. “‘My own garden is my own garden,’ says the Giant; ‘any one can understand that, and I will allow nobody to play in it but myself.’”

The wall he builds separates him from others, and he becomes estranged from the world. The story says that he leaves his ogre friend, the neighborhood children no longer visit him, the birds don’t land in his garden, and even the seasons—at least Spring, Summer, and Autumn—stay far away. In the giant’s garden, “it [is] always Winter there, and the North Wind, and the Hail, and the Frost, and the Snow [dance] about through the trees.” They are his only companions. It is poignantly ironic that by trying to wall in his garden, he destroys its growth, completely preventing it from flowering at all.

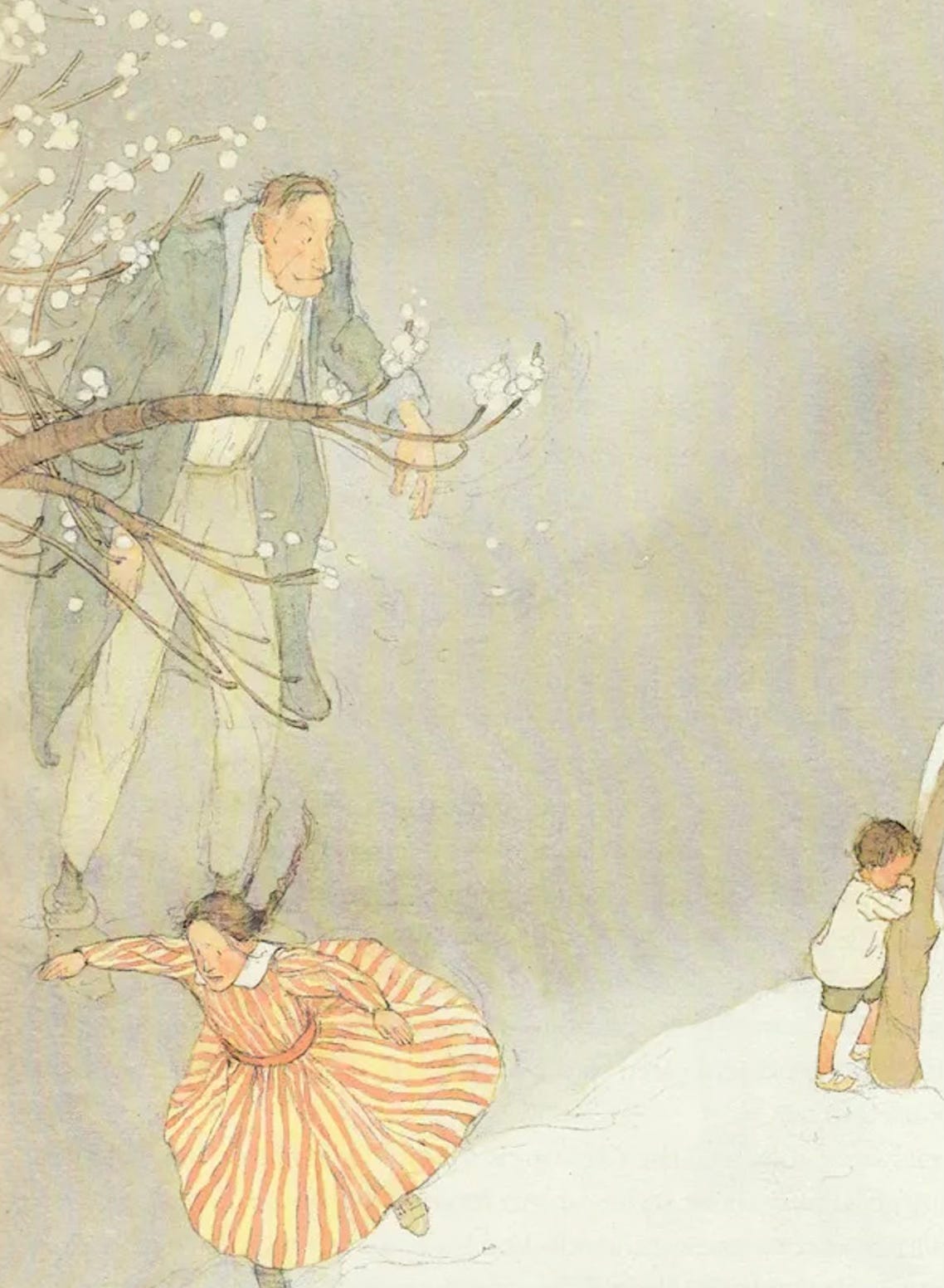

Maybe sorrow and winter eventually wear a hole through the giant’s wall, or maybe steady effort on the part of the children chips away at the wall until they form a hole big enough to enter. The story isn’t clear as to how the children come to break through the wall, but eventually the children do break through to make space for Eucatastrophe. Through the efforts of the neighborhood children, the Giant is reintroduced to music, to the birds, to the sun, and to the soft breezes of Spring. His trees bloom once again, and the children climb them, laughing and having fun.

Even though they have broken into the garden on their own, it is interesting that the first time the Giant appears, the children run away from him. Only Christ, represented by a little boy, is left with the Giant in the garden. The Giant doesn’t know yet who he approaches, but Oscar Wilde makes it clear by the end of the story that the Giant owes his happiness to Jesus Christ, who does not run away from him:

And the Giant stole up behind him and took him gently in his hand, and put him up into the tree. And the tree broke at once into blossom, and the birds came and sang on it, and the little boy stretched out his two arms and flung them round the Giant’s neck, and kissed him. And the other children, when they saw that the Giant was not wicked any longer, came running back, and with them came the Spring. “It is your garden now, little children,” said the Giant, and he took a great axe and knocked down the wall. And when the people were going to market at twelve o’clock they found the Giant playing with the children in the most beautiful garden they had ever seen.

This is a moment of repentance and change. The giant meets Christ and his heart changes. He returns to society, knocks down his wall, and finds joy again.

At One Ment

The Atonement as reconciliation is about a setting “at one” those who have been estranged from God. The metaphor is contained in the word itself—at-one-ment—and it is closely related to the Latin roots for reconciliation re, meaning “again”; con, meaning “with”; and sella, meaning “seat.” Reconciliation means “to sit again with.”

Another word that can help us understand the metaphor of Atonement as reconciliation is the Greek word for sin, which is hamartia. In English, we translate hamartia as a fatal flaw, one that leads to a tragic hero’s downfall, but hamartia arose from the Greek verb hamartanein, which means "to miss the mark, err, and therefore not share in the prize" (Strong’s Concordance of the Bible). If we were using the metaphor of justification, we could look at hamartia as anything that causes us to break the laws of God—to miss the legal mark. When we look at it through the lens of reconciliation, missing the mark is based on relationships instead of legality. In this case, sin is anything that causes us to break or sever our relationship with God, to be estranged or even walled away from him; therefore, to not share in his prize.

Julian of Norwich—14th-century English Anchoress, and author of Revelation of Divine Love—writes about this using the word oned. One-ing is the process of overcoming this estrangement and coming to sit again with Christ. She writes that we are oned with Christ: “when we of His special grace plainly behold Him,” which is a simple act the Giant performed, and “seeing none other needs, then we follow Him and He draweth us unto Him by love. . . . and then we can do no more but behold Him, enjoying, with an high, mighty desire to be all oned unto Him.”

She describes a process of coming to Christ, beholding him, following him, being drawn to him, and then desiring to unify with him. This process is also encouraged in scripture, when Jacob writes, “Wherefore, my beloved brethren, reconcile yourselves to the will of God, and . . . after ye are reconciled unto God . . . through the grace of God . . . ye are saved”” (2 Nephi 10:24). Later he writes again that we should take counsel from the Lord, and “be reconciled unto him through the Atonement of Christ” (Jacob 4:10-11).

Returning to the fairy tale, we see the Giant experience this reconciliation through Christ. He beholds him, not even knowing who he is, then he is drawn to him. In Christ’s presence, he becomes more like him, having a desire to share his garden with others, and he is changed into a new person. Interestingly, when the Giant “sits again” with Christ, he is also oned with his community. He welcomes the children to his garden. Spring, Summer, and Fall return. The birds sing again, and to him, it is glorious music. The transformation of the Giant from a solitary grump to a jolly, joyful figure, rivals some of the greatest transformations in both literature and scripture. It calls up images of Paul the apostle, Ebenezer Scrooge, or even Dr. Seuss’s Grinch, whose heart grows three sizes during his moment of Eucatastrophe. But among the stories in this book, one thing that makes this story unique is the timing of the Giant’s change of heart.

The Good Catastrophe

Often the Eucatastrophe in a fairy story comes at the close of a narrative. The stories we have read so far in this series—“Snow White,” “Beauty and the Beast,” and “Goblin Market”—all end shortly after their respective saviors have carried out their missions. After an inciting incident (sin), we get some rising action when everybody sorts out what to do and how to overcome it, and then (Atonement) the prince carries Snow White off to his castle and marries her, Beauty loves the Beast and breaks his curse, Lizzie returns from the market dripping with the cure for Laura’s woundedness.

But let’s look again at how Tolkien described Eucatastrophe in “On Fairy-stories.” This time, I want to examine some assumptions we have made about these happy so-called “endings” that don’t necessarily find support in Tolkien’s source text:

The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous “turn” (for there is no true end to any fairy-tale) . . . is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur.

Tolkien uses the word “ending” but does Eucatastrophe have to come at the end of a fairy story? Is that a rule? Because if Eucatastrophe is a “sudden joyous turn” and “there is no true end to any fairy tale,” then maybe the turn can come early—maybe we don’t have to wait for the end of a story to see the miracle we are hoping for.

If we want to try to look directly at the Atonement, the ending of the Christian story will be each of us sitting before God, receiving restoration, forgiveness, and healing, and then entering into a kingdom of glory. But what about the healing we are seeking now, in mortality? What about repentance, forgiveness, healing, and restoration in our day-to-day lives?

‘The Selfish Giant” is a better model of our actual experience in one key way: The Giant meets Christ in the middle of his story, not at the end. That meeting changes him. It inspires him to be better, to love others, and to share all that he has. But his story doesn’t end at that point, his life continues forward after the miracle.

“Life with Christ Before We Die”

Through this story, we get a glimpse—a small, metaphorical look—at what comes after Eucatastrophe.

Life goes on. The Giant tears down his wall through work and sweat. He makes his garden beautiful again, pulling weeds and briars. And he opens his life up to others. The story says that the children come and play every day.

There is joy in his life, to be sure, poignant moments of joy. But there is also sorrow. The Giant misses the boy, whom he doesn’t see again. He wonders where the boy is and asks the other children, who have no answer. Most of all, he has to live a long time, and it is a life with Spring, but also Winter. The cold North wind doesn’t disappear forever. It rotates in and out like the rest of the seasons. Some moments are cold and some are warm. But the Giant doesn’t mind anymore because “he knew that [Winter] was merely the Spring asleep, and that the flowers were resting.” Here, the Giant shows his growth. He not only experiences both joy and sorrow, but he has learned to find joy in sorrow, and, like many of us he also experiences sorrow in joy. He has joy and hope in the resting flowers because he knows that they will soon bloom.

In “On Fairy-stories,” after Tolkien discusses the joyous turn of Eucatastrophe, he describes its opposite, “dyscatastrophe”:

[Eucatastrophe] does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and inso far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.

“Walls” is a particularly relevant word to use here as we discuss “The Selfish Giant,” but the language also calls up the experience of Alma in the Book of Mormon, when he writes, “And oh, what joy, and what marvelous light I did behold; yea, my soul was filled with joy as exceeding as was my pain!” (Alma 36:20). Alma, like Tolkien, does not deny the existence of the pain and sorrow as he experiences the hope and light of Christ, he experiences them even in the same moment, remembering the pain and comparing it to sorrow.

The Selfish Giant learns to live with this. He lives with grief and sorrow, and with the joy of Christ. He holds on to his memories of the boy and lets those memories get him through his many winters. One key feature of this metaphor, and one way that it can change our understanding of the Atonement, is that it allows for moments of Eucatastrophe throughout a life. In his book An Early Resurrection: Life in Christ Before You Die, Adam Miller describes this life in Christ:

Living in Christ changes what it means to be alive. Living in Christ, I carry myself differently. I desire differently. I love differently. I greet pain and loss differently. I fail differently. I succeed differently. I part with the past differently. I respond to the present differently. I look to the future differently. In Christ, I hold time itself in a very different way. (p.18)

The difference is that we are reconciling with Christ and God, one-ing our souls and selves with them. Instead of being saved once from jail or healed once from sickness and then—tada—we never have any problems ever again, we find peace and forgiveness over and over again, experiencing exquisite joy and tragic sorrow in many moments.

Repentance

Another wonderful feature of this metaphor comes as we consider what it says about repentance. In the other metaphors we have discussed, repentance is either absent or it comes as a result of guilt or shame. Reconciliation seems to soften the idea of repentance. Yes, the Giant changes. He tears down his wall; he becomes more friendly and less selfish, but he doesn’t do it out of guilt or shame. He doesn’t bemoan his brokenness first. He repents because he wants the good things that come from being kind. He isn’t running away from selfishness, he is running toward the sun and the birds and the children.

In this metaphor, Christ’s very presence incites change in us. As we come to spend more time with him, we want to be different. We want to be like him. It is not about obeying him because he has mediated or brokered a deal with our debt collectors. It is not about him fixing something that is broken within us. Reconciliation is very much about our own desire to come closer to Christ and our heavenly parents and to be more like them.

If we use the metaphor of reconciliation to structure our understanding of Atonement, then prayer, contemplation, scripture study, and church attendance are motivated not by the idea that we have to keep these commandments to earn our salvation, but that we want to know and understand God better, and we do this by doing godly things.

The Giant (we won’t call him selfish at this point in the story) spends the rest of his life seeking Christ. He asks the other children about him, watches for him, waits for him. His whole life is shaped by the vision of forgiveness and acceptance that he receives from Christ in a single moment. In this metaphor, the Giant plays an active role in his salvation by striving for reconciliation with the Savior, seeking him out again and again, and living with others as if the Savior were present.

In the book At One Ment, Thomas Wirthlin McConkie writes of this journey, “To at-one, then is not a singular act so much as a natural process. It is the nature of Nature. Atonement stands revealed in the evolving reality of Christ in our own developing godhood, that all may be One” (202). Reconciliation is a process of repentance and one-ing that takes a lifetime.

The Giant does this. He spends his life reconciling, and then, at the end of the story, long after the first Eucatastrophe, he dies. In death, he meets Christ again. “Who art thou?” he asks. “And a strange awe [falls] on him, and he [kneels] before the little child.”

In this second Eucatastrophe, the Giant meets his Savior again and hears, “You let me play once in your garden, to-day you shall come with me to my garden, which is Paradise.”

Chanel Earl is a writer—mostly of fiction—who currently teaches writing at Brigham Young University.

Art by Wladimir Dowgialo, Everett Shinn (1876–1953), Lisbeth Zwerger, and Walter Crane (1845–1915).