Click above to read an English translation (Andrew Lang) of the classic French fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast,” originally written by Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve (1685–1755) and abridged and summarized by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont (1711–1780).

The justification metaphor dominated my religious education growing up. This is partly because the scriptures, especially the Book of Mormon, rely so heavily on this metaphor, but also because some of the great stories that inspired feelings of gratitude and love for my Savior used this framework for understanding.

Although it has many variants and can get as complicated as we let it, the basics of the justification metaphor can be explained simply.

When we break God’s laws (sin), we are declared unfit to return to God. Jesus Christ then steps in as our Savior, pays the price for our sins, and, in essence, buys or earns salvation for those who follow him. Boyd K. Packer’s “The Mediator,” which I mentioned in the introduction, uses this metaphor and has deeply influenced my understanding of the Atonement. Aslan (spoiler ahead!) giving his life for Edmund in C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is another metaphor that conceptualizes the Atonement as justification.

Nephi teaches about the Atonement using this metaphor in the Book of Mormon:

And the law is given unto men. And by the law no flesh is justified; or, by the law men are cut off. Yea, by the temporal law they were cut off; and also, by the spiritual law they perish from that which is good, and become miserable forever. Wherefore, redemption cometh in and through the Holy Messiah; for. . . . Behold, he offereth himself a sacrifice for sin, to answer the ends of the law. . . . (2 Nephi 2:5–7)

Others also look at the Atonement in this way. Mosiah does when he writes that God gave “the Son power to make intercession for the children of men . . . standing betwixt them and justice; having broken the bands of death, taken upon himself their iniquity and their transgressions, having redeemed them, and satisfied the demands of justice” (Mosiah 15: 8–9).

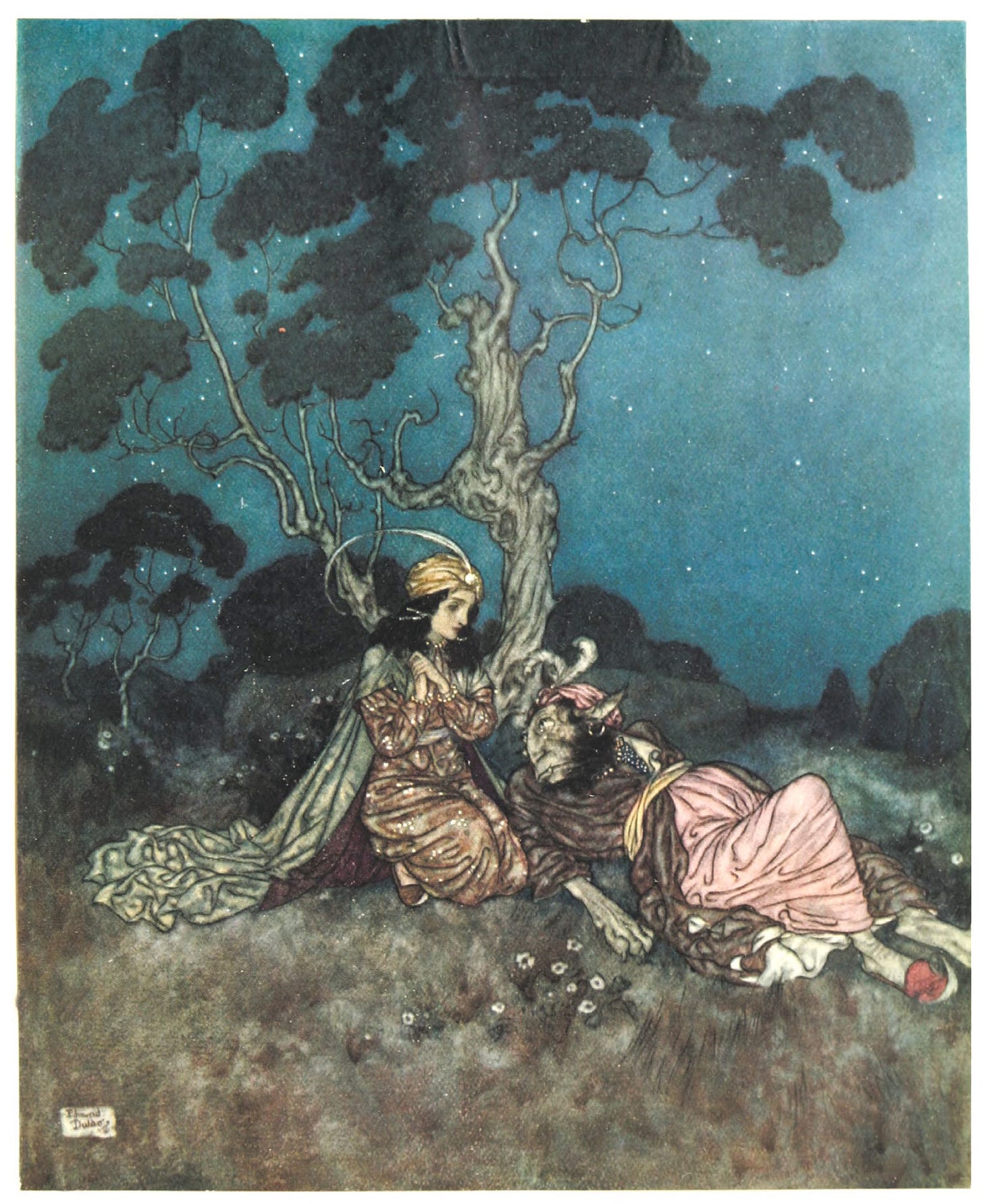

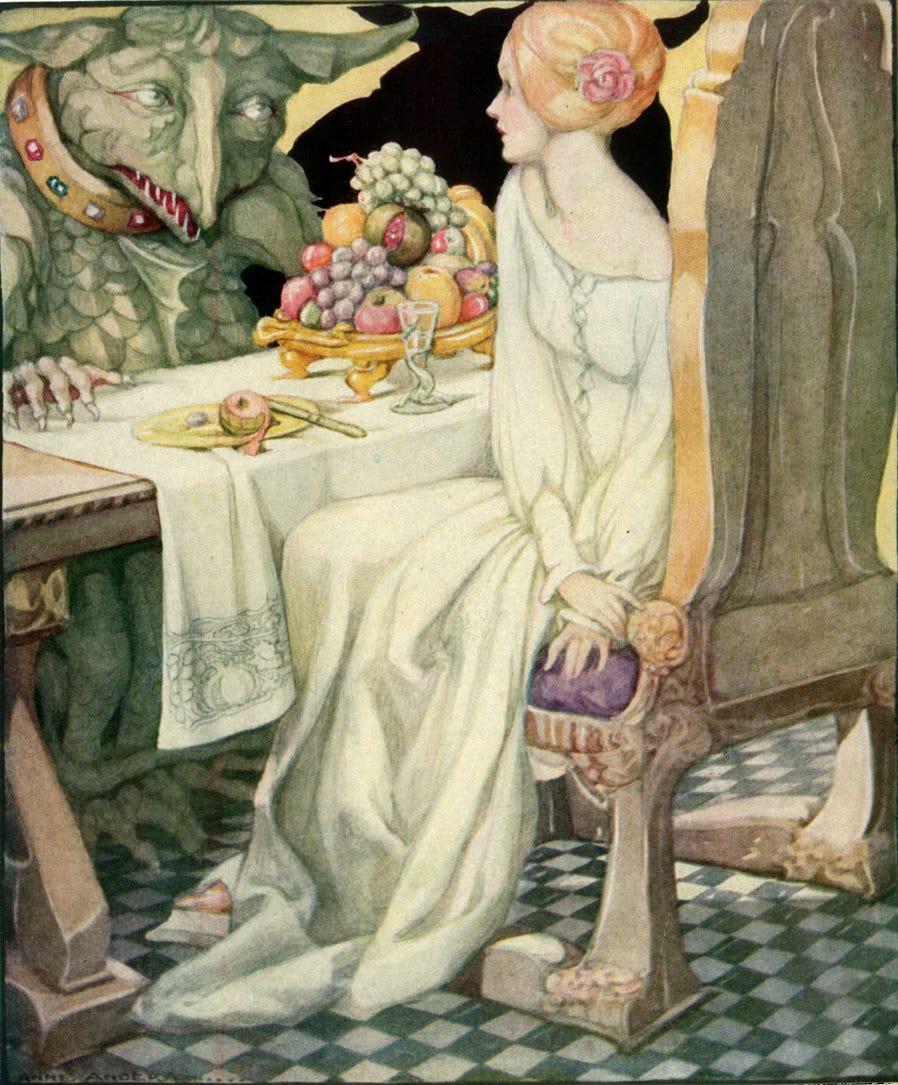

Beauty and the Beast

Many fairy stories illustrate this metaphor, but Beauty and the Beast is an excellent example because it is a popular story with metaphorical possibilities that often go unnoticed. Those who watch, hear, and read this tale are often so absorbed with the story’s drama that they don’t think about what is going on metaphorically. This is also a lovely example of justification because its conclusion expands the idea of justification to create a powerful eucatastrophe worthy of the powers of the Atonement. We will look at that conclusion at the end of this essay, but first, let’s look at how the story begins.

Much like in the Book of Job, there is a merchant—a family man with a big house, many children, and riches to spare. He has “until this moment prospered in all ways.” Then his house burns down, and his “books, pictures, gold, silver, and precious goods” are gone. He is betrayed by his clerks in distant countries, his ships sink, and he and his family are left in poverty. Unlike Job, his children do not die, but they are—with one exception—upset at him, and they moan and murmur about their newly impoverished state, especially after all of their friends desert them.

When the merchant and his family move, impoverished, to the woods, his daughter Beauty is more fully introduced. She has never been upset at her father, nor has she had any trouble adjusting to her new simple life. She is the most beautiful, kindest, hardest working, and just all-around best person in the story. Like in the story of Snow White, her beauty—and other positive traits—indicates her goodness. She is the hero of this story, and we can see her as a vehicle for the Savior.

Beauty is the only one of the merchant’s children who is cautious when good news arrives that their fortune may soon be restored, and while her sisters ask their father for fancy ball gowns and jewelry when he returns from a trip in search of his lost wealth, Beauty asks her father to bring her a single rose.

The merchant does not find a fortune and ends up “as poor as when he started.” Then, on his return trip, he gets lost in the woods (often a vehicle for life in the world) on a cold, dark, and stormy night, and the real story begins.

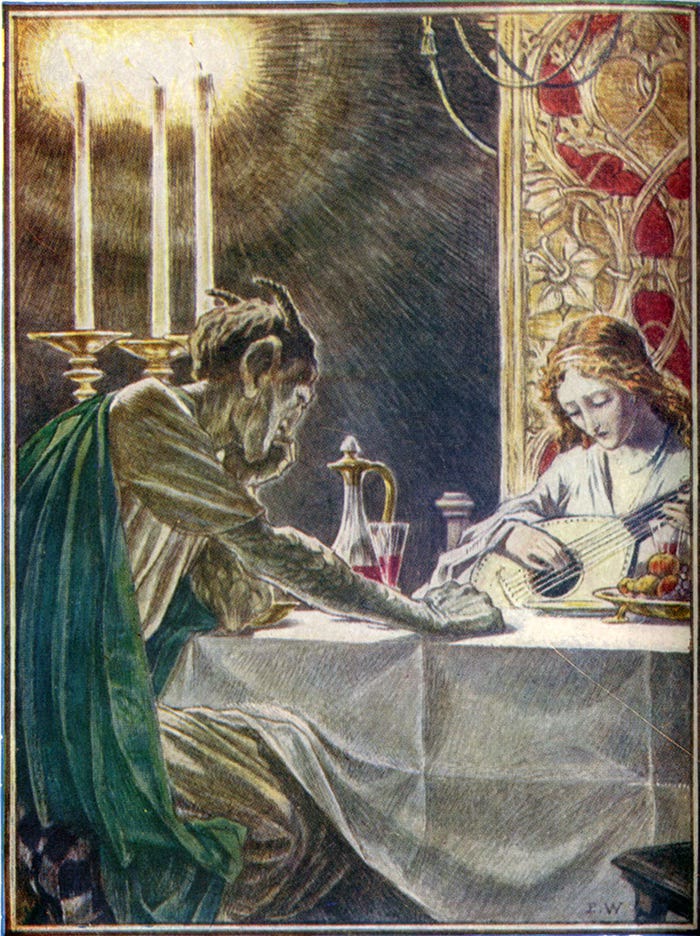

He wanders into a castle. Although the merchant doesn’t know it yet, the castle belongs to the Beast, and the Beast allows him to roam freely within, provides a dry stable and food for the merchant’s horse, food and drink for the merchant, shelter and a place to sleep, and allows the merchant into his enchanted garden where, “though it was winter everywhere else, here the sun shone, and the birds sang, and the flowers bloomed, and the air was soft and sweet.” The garden is a magical paradise, a perfect place where all things bloom and grow (I hope you can see what it could represent). When the merchant sees the roses blooming so abundantly in the garden, he is reminded of his promise to Beauty, and he plucks a rose for her.

The rose is almost universally seen as a symbol of love, and we can easily see the rose as a representation of the love the merchant has for his daughter. But we can also see the rose as a more complicated religious symbol, one relevant to our discussion of Atonement. It is a red rose, the color of blood, and along with the beautiful blossom of the rose come sharp thorns. Much like Snow White’s apple, readers might recognize it as a vehicle for the fruit of the Garden of Eden. A fruit that is both desirable and dangerous. Immediately as he picks it, the merchant meets the Beast, who condemns him to death.

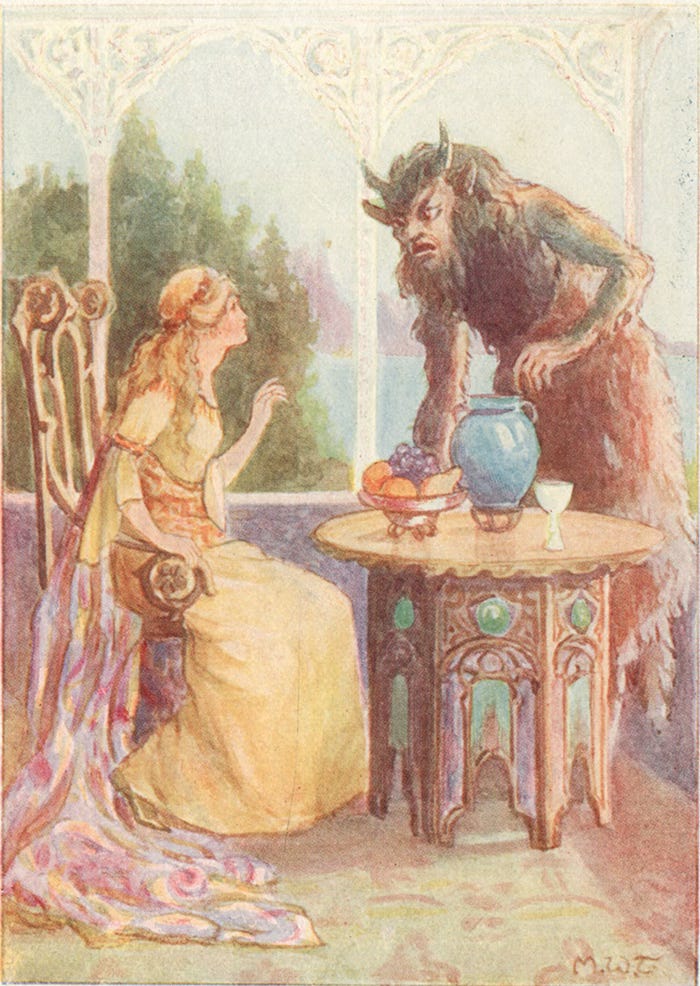

The Beast is an imposing figure. He is frightful, terrible, angry. He has been a generous host to the merchant, but picking a rose is taking the Beast’s hospitality too far, and now the Beast decrees that the only way that the merchant’s life will be spared is if one of his daughters takes his place in the Beast’s castle. But she must “come willingly.” She must be “courageous enough,” and love her father “well enough to come and save [his] life.”

This is the moment where Beauty steps into the role of Christ and makes the choice that will lead to the justification of her father. She agrees to set things right. She takes the punishment that should be her father’s and, in so doing, justifies him in the law laid down by the Beast. Her father is then spared from death and allowed to return to his family.

The Power of Metaphor

The idea of justification that is represented in this story—of bringing ourselves in line with justice through the assistance of a savior or mediator—is so common and widely accepted in the Church that much of the language we use when we talk about the Atonement carries the idea of justification with it. In writing about other metaphors in this series, I struggled not to use words like law, justice, and “paying the debt.”

The idea is so common that we hear it everywhere, including in these lyrics from several of our sacrament hymns. Although the metaphor of justification might not be intended as the main subject of each of these hymns (it probably is in some of them), the language alludes to justification throughout the entire set:

Hymn 187: He died in holy innocence, / A broken law to recompense.

Hymn 190: The body bruised, the lifeblood shed, / A sinless ransom for our sake.

Hymn 191: Behold the great Redeemer die, / A broken law to satisfy.

Hymn 193: That he should extend his great love unto such as I, / Sufficient to own, to redeem, and to justify.

Hymn 194: There was no other good enough / To pay the price of sin.

Hymn 195: How great, how glorious, how complete / Redemption’s grand design, / Where justice, love, and mercy meet / In harmony divine!

Hymn 197: By heaven’s plan appointed, / To ransom us, our King.

Other phrases that carry with them the implication of justification include bought with his blood and died for our sins. The titles Advocate, Mediator, and Judge are decidedly legal terms. And Christ, Messiah, Lamb of God, and Scapegoat are linked to ancient Hebrew purification practices of animal sacrifice, Christ and Messiah meaning “Anointed,” referring to the preparation of the animal being sacrificed in the stead of the sinner.

The prevalence of this metaphor brings about an interesting change in the way the metaphor operates. Instead of justification being merely one way of looking at the Atonement, the idea begins to structure our understanding of Atonement more directly. It becomes a conceptual metaphor.

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson first discussed conceptual metaphors in their book Metaphors We Live By, where they propose that conceptual metaphors have the power to change the very structure of their tenors in the minds of those who use them. Conceptual metaphors become so ingrained into our lives and language that they inform the way we interact with, experience, and behave when confronted with the concepts they represent. This, in turn, can affect our entire way of being, our actions, our relationships, and our thoughts.

Lakoff and Johnson use the conceptual metaphor “time is money” to illustrate this. In Western culture, we talk about time as money, we spend it, save it, budget it, and even run out of it. This concept has changed the way we think of time. We could think of the abstract idea of time in many ways, but we have structured our understanding of it in this particular way, viewing it as a valuable commodity and a limited resource.

These kinds of conceptual metaphors occur in many facets of life, and they can also change our religious understanding. If we conceptualize the Atonement as a legal process—which we do—it changes our relationship with our Savior. It demands certain actions, shapes the way we view ourselves, and forms the basis of our understanding of the plan of salvation. And if that is the only metaphor we live by, then we will have a relationship with our Savior that is based on good things like gratitude for saving us from our debts or defending us in court, but also potentially harmful things like seeing Christ as a businessman counting his money or God as a judge determined to condemn as many of his children as possible.

This metaphor has received scathing criticism (a good introduction to the criticisms of this metaphor can be read in chapter 13 of All Things New, by Fiona and Terryl Givens) for the way that it turns all of mankind into criminals, the way that it makes Christ’s mission about suffering instead of succoring, and the way that it frames God as distant and uncaring, willing to condemn either mankind or Jesus Christ to eternal suffering.

The justification metaphor can be explained simply, but as we look at the ways it could be interpreted, we find that it doesn’t stay simple for long. There are many variations on the theme of justification. I have been lumping a lot of different Atonement theories together under this single “justification” umbrella because they all relate to condemnation and justice, but whole libraries have been written analyzing and explaining their variations. We won’t be able to do these discussions justice, but we do have time to discuss a few elements of the conversation here as we continue our look at Beauty and the Beast.

Complicating Justification

The earliest examples of this metaphor give the power of judgment not to God but to Satan.

Benjamin Dearden writes in “Why Do We Need an Atonement?” of the classic Atonement paradigm found in such scriptures as Matthew 20:28, which says that “Christ will give his life a ransom for many.” This ransom metaphor posits that once a person sins, they belong to the Devil and that Christ, through his Atonement, pays the Devil’s ransom and purchases sinners with his blood.

This is a fascinating theory to think about with Beauty and the Beast in mind. If we metaphorically name Beauty’s father as the vehicle for mankind, the Beast as the vehicle for the Devil, and Beauty as the vehicle for Jesus Christ, this part of the story cleanly illustrates how a broken law could condemn a man and how another could step in to save him.

Most modern discussions of Atonement do not allow Satan the power to hold God’s children for ransom. More often now, God himself condemns mankind because we fall short of heavenly standards. This gives the power to justice itself. This variation of the justification metaphor posits that all of God’s children must stand before him as he serves as a judge and is forced to condemn those who fall short of the demands of justice. As they receive their guilty verdict, even during their sentencing, Christ steps forward as a scapegoat and acts as the substitute for them, taking their punishments himself and meeting justice’s demands.

This variation of the metaphor is often referred to as penal substitution and is the theory that Alma describes to his son Corianton:

And thus we see that all mankind were fallen, and they were in the grasp of justice; yea, the justice of God, which consigned them forever to be cut off from his presence.

And now, the plan of mercy could not be brought about except an Atonement should be made; therefore God himself atoneth for the sins of the world, to bring about the plan of mercy, to appease the demands of justice, that God might be a perfect, just God, and a merciful God also. (Alma 42:14–15)

By this theory, Christ atoned for the sins of the world not to pay the price to the adversary, but to justice itself, and to God, whose eternal laws demand certain punishments for certain sins.

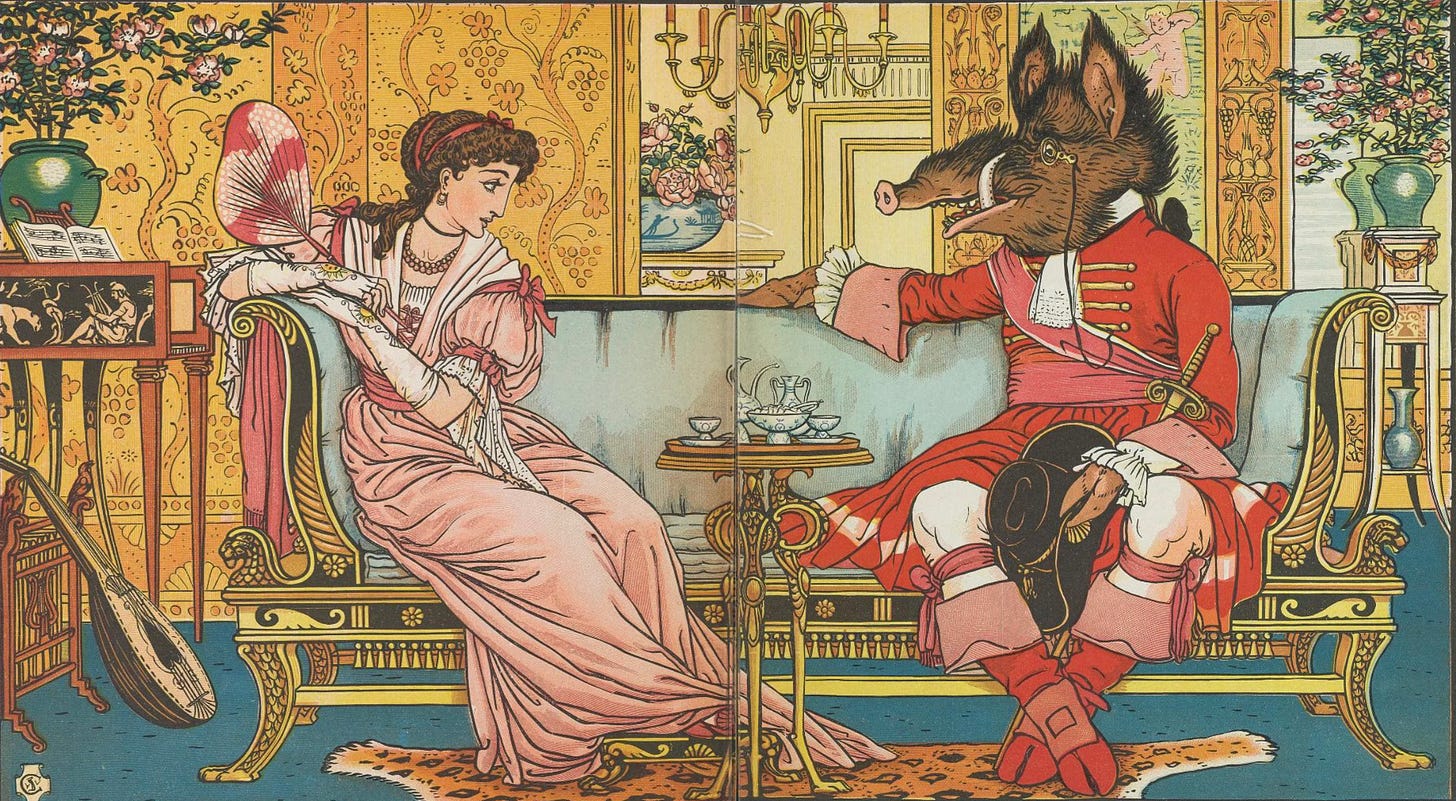

There are a few key details in Beauty and the Beast that allow for this interpretation. First, the Beast is an immovable force. His strength and power make him a good stand-in for God’s justice, which is seen as similarly immovable. Justice cannot be robbed (Alma 42:25). It cannot be changed. It is a fixed law that none can escape.

The second detail that allows us to interpret the story in this way is Beauty’s goodness. She would, in the context of this metaphor, represent mercy, who chooses out of her great love to take this punishment. As Alma explains in the same chapter, when “justice exerciseth all his demands . . . mercy claimeth all which is her own” (Alma 42:24). Beauty claims her father and his punishment when she volunteers to take his place.

Alma’s explanation of the metaphor of penal substitution is very persuasive, but Amulek, his friend and missionary companion, took issue with it. He agrees with Alma that it is expedient that an Atonement should be made, but asserts that it would not be a simple substitution. The atoning sacrifice must be greater:

Now there is not any man that can sacrifice his own blood which will atone for the sins of another. Now, if a man murdereth, behold will our law, which is just, take the life of his brother? I say unto you, Nay.

But the law requireth the life of him who hath murdered; therefore there can be nothing which is short of an infinite Atonement which will suffice for the sins of the world.

Therefore, it is expedient that there should be a great and last sacrifice. (Alma 34:11–13)

This argument leads to an understanding of justification that goes beyond the simple math of “A punishment is owed, and I can’t pay it, so Christ is paying it for me.” In Amulek’s justification theory, Christ must suffer an infinite punishment, paying an infinite price. That infinity is great enough to cover all of justice’s demands eternally. Amulek’s justification is not about giving Satan what he is owed or appeasing the law on an individual level, it is about Christ breaking justice and carrying out a mission of infinite mercy, a mission that can save everyone who comes to him.

Does Beauty do this?

Return to Eucatastrophe

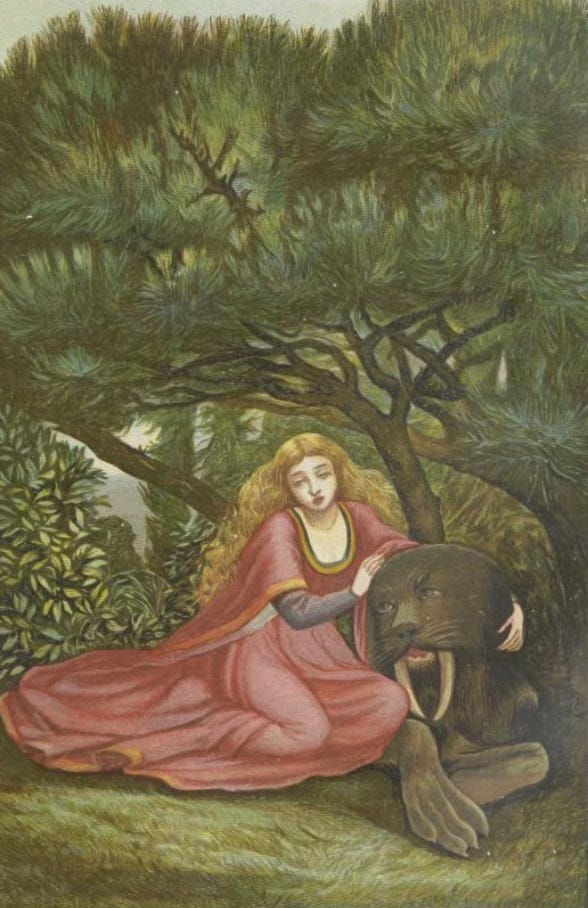

After Beauty enters the Beast’s castle to save her father, the story veers into beautiful, new territory when Beauty redeems not only her father but others as well.

Remember, this story is not an allegory, and none of the characters perfectly represent single players in the plan of salvation. That is why, in one moment, the merchant can represent Adam, plucking a rose in the garden to his condemnation, and the next, he can represent each of us. The Beast can be Satan in one reader’s eyes and justice in another. And Beauty, who I have stated represents Jesus Christ as she saves her father from condemnation, can quickly come to represent each of us as she learns to love the unlovable, the Beast being foremost among them (I like to hope I can one day be like her).

No one interpretation is “the true interpretation,” but I think some interesting spiritual ideas resonate through the happy ending—the eucatastrophe—of the story. Here, Beauty goes beyond mathematical justification or penal substitution. I wouldn’t say her act of sacrifice is infinite or eternal, but the consequences of her action are certainly magnified.

First, she not only frees her father from death, but she also frees her entire family from poverty and suffering because when she stays in the castle, her father is given the riches that her siblings have so long desired. She restores them to wealth and prosperity.

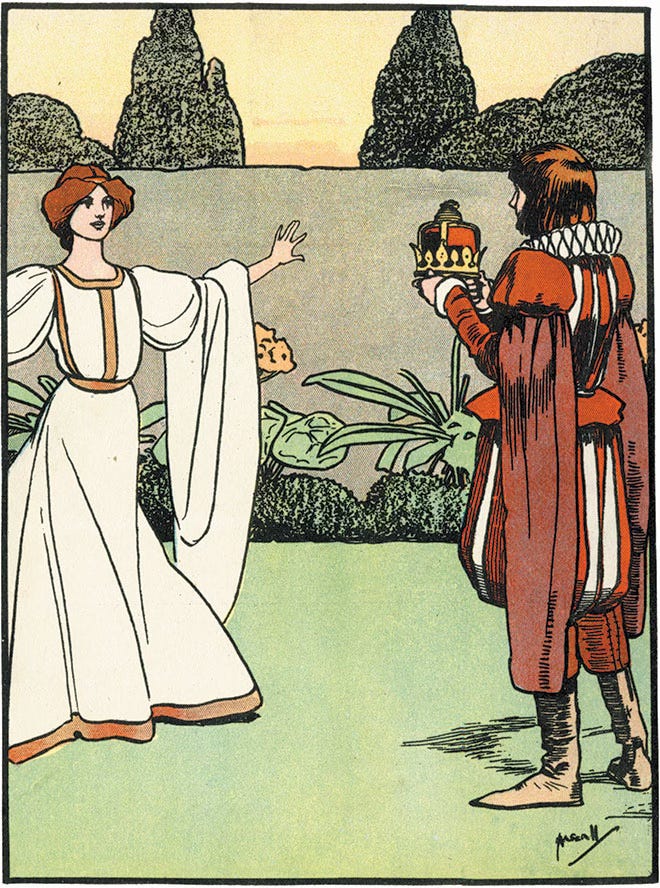

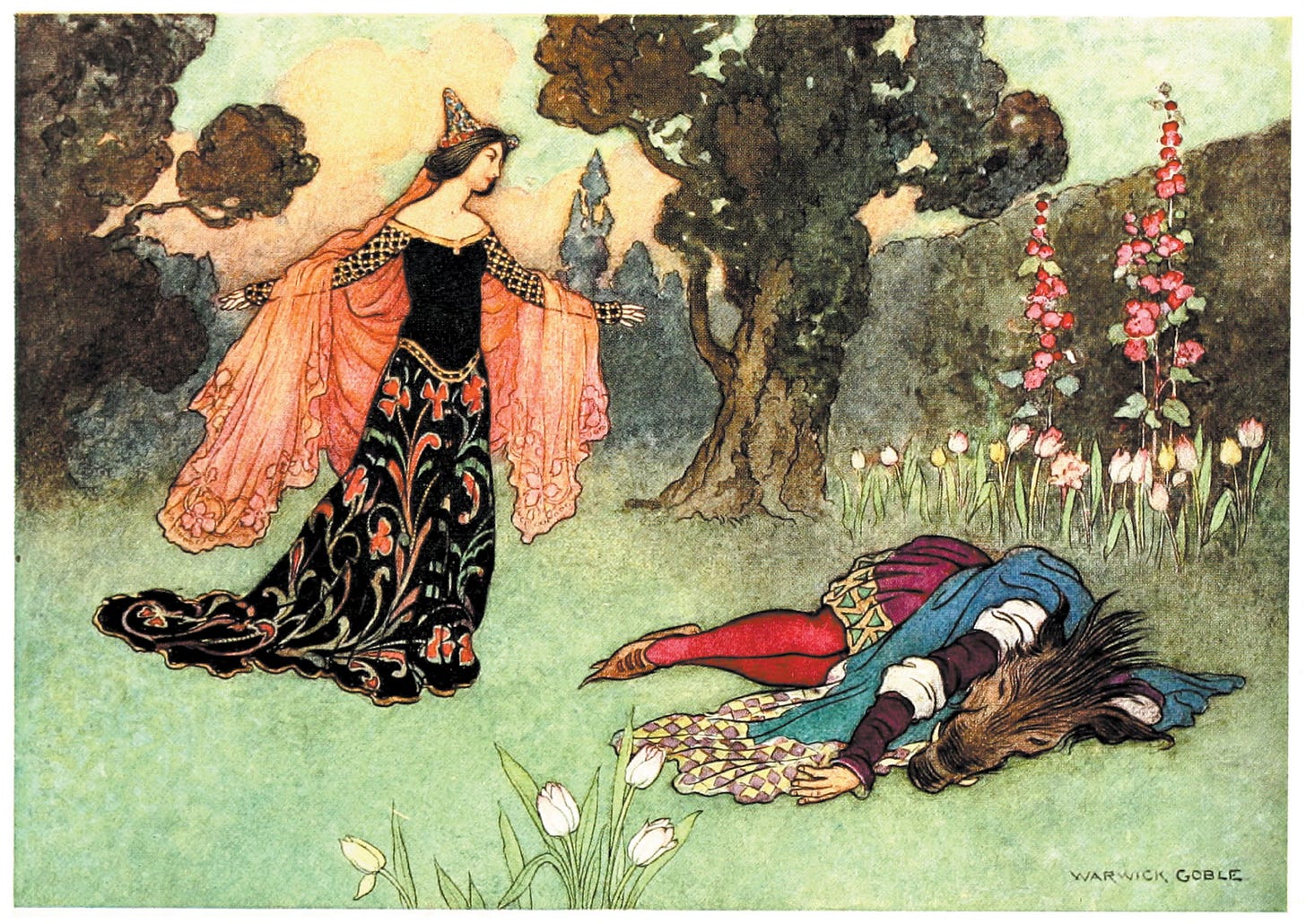

Then, Beauty has beautiful dreams about a handsome prince who is calling for her to save him. This prince is the Beast, and when he is freed from his curse in the end, he and his mother are also made happy.

In possibly the most popular film version of the story (the Disney animated feature), the prince’s entire household is also cursed. His whole kingdom has fallen into disrepair and despair, every member of his court transformed with him. Beauty saves them all.

This is the power of justification. It may look like a simple mathematical equation or a righting of a wrong, but when Christ chose to atone for mankind, he did not atone mathematically; his sacrifice wasn’t about numbers, economics or arithmetic. He atoned infinitely, and his infinite sacrifice brings forth infinite and eternal joy and consolation. When Beauty agrees to go to the Beast’s castle in her father’s place, she does it out of love for her father, and that love is magnified. It ripples through the story to save everyone: her father and siblings, the Beast and his family and people. Beauty saves them all in a miraculous and unexpected ending that reminds us that the Atonement isn’t a legal math equation but an infinite and eternal justification of all creation.

Chanel Earl is a writer—mostly of fiction—who currently teaches writing at Brigham Young University.

Art by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), Paul Woodroffe (1875-1954), Margaret Tarrant (1888-1959), John Hassall (1868-1948), Anne Anderson (1874-1952), Eleanor Vere Boyle (1825-1916), Beauge Bertall (1820-1882), Walter Crane (1845-1915), Warwick Goble (1862-1943).