Why Do We Need an Atonement?

A Modest Exercise in Soteriology

The field of Atonement studies, a sub-branch of Soteriology (study of salvation) asks us to consider why salvation requires an atonement. While throughout the religious history of the world, prophets, theologians, and believers have felt the intuitive need for Atonement or reconciliation with God, Atonement studies provides a language to talk about exactly what the atonement provides to each of us. As an illustration of why this language and understanding of the “mechanisms” of Atonement, a counterfactual might help frame these questions more clearly. Imagine a world with divine guidance and revelation, but without a Savior. In this world, everyone lives, sins, tries again, some get better, some don't, and eventually, Judgment Day arrives. On Judgment Day, God gets up and says to his children: “Wow, great job guys. I’m so proud of all of you. Everyone made mistakes, but that’s okay, it’s all in the past now, so anyone who wants to, come on with me to the Celestial Kingdom, and if you aren’t interested in that, feel free to go to a different kingdom.” Then, without further ado, Atonement, suffering, or process of reconciliation, everyone shuffles off to where they feel most comfortable. Perhaps intuitively, some readers will feel that there is something lacking in that scenario. The aim of the field of Atonement studies is to point out what. Who would object to an easy slide into salvation, with no price paid, and why?

This essay aims to give a brief overview of those Atonement theories, namely, the ransom theory, the objective paradigm, the subjective paradigm, and the more modern Girardian approach. It also provides some of the most common metaphors that help us understand each theory. Finally and most importantly, it suggests additional insight from some of our own emblematic stories as Latter-day Saints as well as our revealed scriptures, beginning the process of delving into the possibilities or our modern-day revelation to open new soteriological explanations for the Atonement, providing insight that may help us to focus on Christ again.

Why Soteriology?

Along with the Creation and the Fall, the Atonement is one of the three pillars of the Plan of Salvation, the central acts defining existence. We discuss and appreciate it frequently at every level of the Church, from Family Home Evening to general conference. Despite this central focus, many teachers spend little time on the “Why?” of the Atonement beyond cursory answers and tautologies, preferring to focus on the “Who, when, and how?”

Of course, the Church does offer simple answers to the question of “Why the Atonement?” Likely, many readers answered the question already, that the Atonement was necessary because of sin. But this isn’t a real answer, it just pushes the question a step further back. If God’s goal is allowing for the salvation of God’s children, why does the existence of sin necessitate an Atonement? If you answered, “Because no unclean thing may dwell in the presence of God,” at the risk of sounding like a toddler, I would respond: “Why can no unclean thing dwell in the presence of God?” Of course, this game could continue off a few steps in any direction, but at this point, it may be best to avoid the infinite regression and survey what other thinkers have done to get at the heart of this question: Why do we need an Atonement?

Not surprisingly, there is a long and rich tradition of Atonement theories in the field of Christian soteriology.1 Throughout the years, they have developed many reasons for why it was necessary that Christ perform the Atonement, some of which are complementary, others, contradictory.

Ransom to Satan

The first pre-medieval answer, known as the classic paradigm, assigns the impediment to an Atonement-free salvation to a familiar foe, namely, the Adversary, Satan. In the earliest explanations of why the Atonement was necessary, Satan was the one holding us back from a salvation without repayment. In this theory, Satan is the rightful owner of sinners, and isn’t that what the scriptures say? Aren’t those who sin “slave[s] to sin?” (John 8:34). And who is the master of sin if not Satan? So, in this theory, the Atonement was a price paid to Satan, to set us free, to purchase us from out of his power. The most popular metaphorical representation of this theory is probably from C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. In the children’s book, Edmund has sold his family for a few boxes of Turkish Delight, and in doing so, sold himself as well. Later, the White Witch (representing Satan) goes before Aslan (representing Jesus) and boldly declares that “every traitor belongs to me as my lawful prey and that for every treachery I have a right to a kill.”2 Aslan does not dispute this assertion but offers himself as a sacrifice instead, paying himself instead of the guilty traitor as the price to the White Witch. In this scenario both Christ (Aslan) and the rest of humanity (his betrayed family, Peter, Susan and Lucy) are willing to let Edmund’s sins go unpunished, but Satan (the White Witch) stands up and intervenes, requiring a ransom. Thus, in the first explanation of why we need an Atonement, we need it because Satan is owed a ransom, and God offers himself as that price.

Objective Paradigm

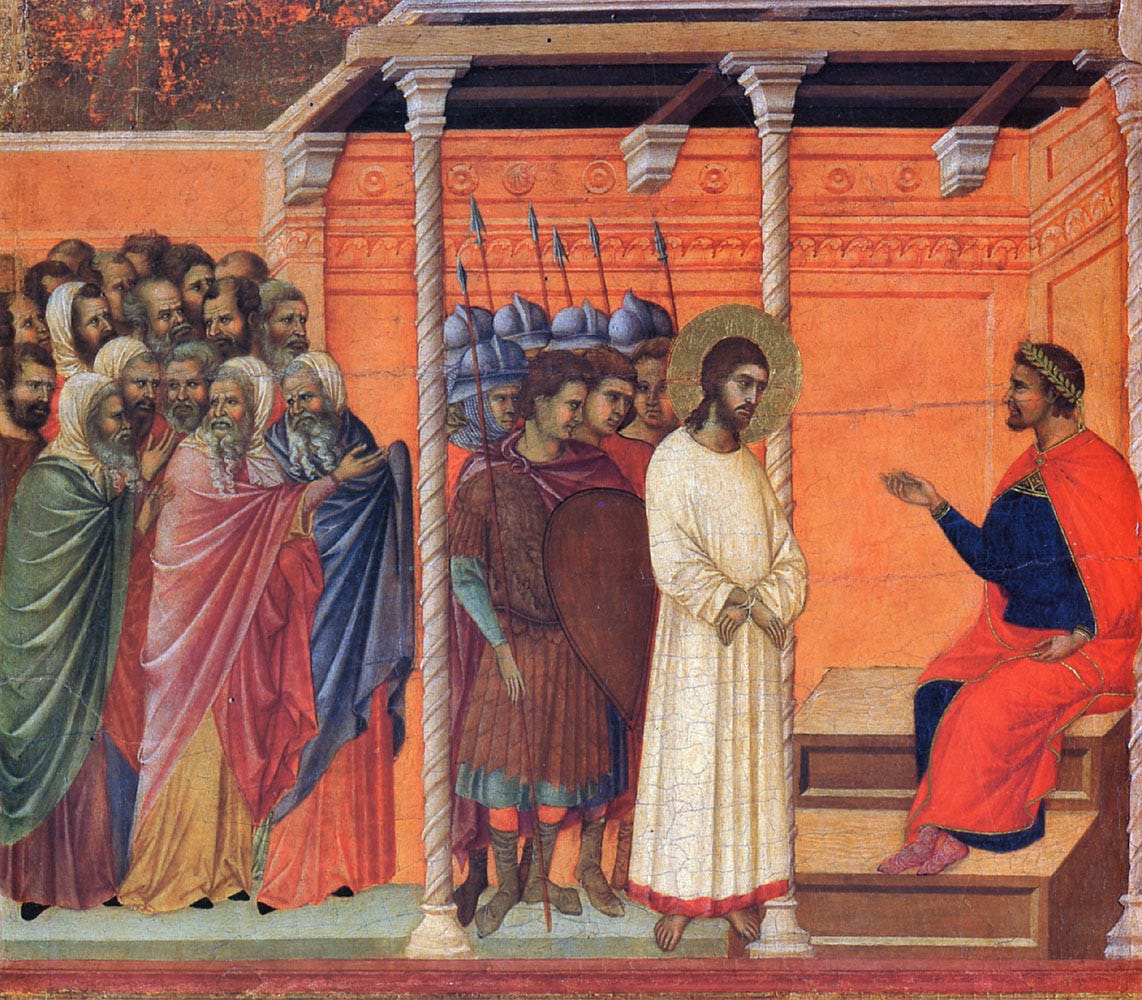

The second explanation, or the objective paradigm, similarly dates back to the Early Church and casts Satan as a minor character, whose work is done long before the final judgment.3 The typical explanation here holds that the Atonement is a price paid to God. Though there are many versions of this paradigm, the one most familiar to Latter-day Saints is that of penal substitution, which posits that God’s nature (specifically his justice) requires that a price be paid, while his mercy requires that his children be given an opportunity to repent. Thus, Christ volunteered to pay the price for everyone, substituting himself for us and being punished in our place, allowing us to live under the law of mercy. Some versions of penal substitution show up in many familiar Church teachings, including Boyd K. Packer’s parable of the debtor, but the version I heard first was the story of Big Billy. In this simple parable, a teacher and his students are starting their first day of class, and they all sit down and write the rules together, agreeing on the rules and punishments, which includes a whipping for breaking the rules. Later on, a student is caught stealing food, and everyone agrees that he must be whipped, but when he takes off his coat to be hit, everyone can see from his underfed and emaciated body that he doesn’t deserve a beating, and they start begging the teacher not to hit the boy. Still, the rules demand that a beating be dealt out, so the teacher raises his yardstick to start. Before it can fall, Big Billy, the strongest and bravest boy in the class, stands up and volunteers to take the whipping instead. In this example, again, the fellow classmates (representing the rest of humanity) don’t want to see anyone punished, and Satan is entirely absent, except in possibly tempting the boy to steal. The only one who is requiring a whipping is God, or more specifically, God’s rules, his justice, as exemplified in the classroom rules and punishments. Unlike in the ransom to Satan theory, this penal substitution serves God’s needs and interests, not Satan’s.

Something that these two theories have in common is that both of them posit a real, objective price to be paid, that is, there is some cosmic debt that the Atonement is meant to repay; they differ primarily on whether that debt is to God or to Satan.

Subjective Paradigm

The third model, the subjective paradigm, rejects the notion of a debt and instead posits that the person or group satisfied by the Atonement is us, God’s children. Theories that come out of this paradigm, such as the moral example or moral influence theories, claim that the primary purpose of the Atonement was not to repay some debt to some cosmic being, but rather to convince God’s wandering children to return to him.4 In these theories, the Atonement is a representation of God’s love, and in contemplating that act, mankind will find the motivation to leave behind sins and repent. A perfect example of this theory in action might be a person who sins and feels worthless (or who sins but is too busy and distracted with the things of the world to truly improve) and then comes across the image of Christ suffering on the cross, and subsequently rethinks their life, their relationship with God, and the direction of their eternal journey. There aren’t many metaphorical explanations for subjective theories, but many hymns reference the basic idea. The most elementary in the LDS canon might be, “To Think About Jesus,” in which contemplating the Atonement and acknowledging his awesome debt to Christ helps a child to conform their behavior to what is expected of them (namely, reverence during the sacrament). In other words, in the subjective theory of Atonement, no price need be paid. The person stopping us from entering into the Kingdom is ourselves; without the Atonement to remind us that we want to be with God, we might simply not heed the invitation to come to him.

All three of these overarching theories have their strengths and weaknesses. In the Ransom to Satan theory, the Atonement ends up feeling more like a (forced?) bargaining chip than an act of supreme grace and love, and it also invites the question, why does God need to listen to Satan’s demands? The objective theories can cast God as an inflexible judge, rather than a loving Father; after all, what good teacher or good parent insists on draconian punishments even when a child has repented, merely because the law is the law and they won’t make any exceptions? The subjective theories sound nice, but if the Atonement is just a good example, meant to set us thinking about God’s love, how is it substantively different from, say, Paul’s crucifixion, or the brave and selfless deaths of many martyrs? In other words, it’s powerful if someone dies to save you from objective danger, but if they die just to show you how much they love you, despite there being no real peril or price to pay, what is there to be grateful for? Conversely, if they die because without dying, they could not save you, then from what would they be saving you and why? Either way we’re still without a clear explanation.

Girardian Atonement Theories

In an attempt to move beyond these hoary explanations (which have existed since at least the 1100’s), more modern thinkers have proposed alternative theories. One of the most interesting and relevant to members of the Church is that of René Girard, a Catholic convert well known for his lifelong study of the concept of mimetic desire, a concept that plays into his explanations of the necessity of the Atonement. Mimetic desire is the notion that people desire things not because they want the things themselves but rather because other people around them desire those things. For instance, no one develops a spontaneous desire for Furbies, Silly Bands, or pet rocks, but knowing that others desire those things makes average people want them too. This leads to escalating cycles of desires, to competition, and eventually to rivalry and violence, or in Girard’s words, “reciprocal escalation and one-upmanship.”5 In Girard’s atonement theory, Satan’s next trick is to provide a “solution” to these tensions through the scapegoating mechanism. As the name implies, the scapegoating process involves choosing a marginal person or group as the “true” source of the community’s underlying tensions, and killing or exiling that person or group, which unifies the previously divided community against a new outsider, and appears to solve the problem. However, this act of violence against the outsider doesn’t actually solve the problem of mimetic desire—it merely resets the tension and starts the cycle of violence again.6

As applied to Christ’s life, this theory posits that Christ’s role was to come to Earth and prove the ultimate futility of such an approach, in that, by being resurrected after suffering the community’s unjust violence, he demonstrated that the cycle of violence doesn’t solve the underlying problems and is in fact no more than another demonstration of our fallen natures. In some ways, this theory is the inverse of other Atonement theories, in which God sends Christ to bear our sins; in Girardian theories, we are the ones who are scapegoating Christ. His resurrection in the wake of our killing him is what saves us. In the words of one Girardian scholar, “Jesus didn’t volunteer to get into God’s machine, [he] volunteered to get into ours.”7

Another way that some critics have discussed Girard’s theory is that, according to Girard, Christ has “saved [us] from salvation,” namely, the salvation that we attempt to create for ourselves, the salvation that always ends with a violent “cleansing.” In the legal world, there is a term called “self-help,” which doesn’t refer to self-help books, but rather the tendency of people in the absence of fair courts and rehabilitation programs to take the law into their own hands, devolving into escalating blood feuds. Similarly, in the field of medicine, people who attempt to treat their own physical or mental conditions (often with alcohol or drugs) are referred to as “self-medicating.” In the Girardian theory, Christ has saved us from spiritual self-help, (in the same way that a fair justice system can save people from extrajudicial self-help) and saved us from spiritual self-medication (the same way that good doctors and caring social supports save people from self-medication). In demonstrating the futility of this spiritual vigilantism and in promising God’s grace, Christ’s atonement freed us from cycles of violence here, now, on this Earth. And so, in rejecting our own instincts (alternatively, Satan’s suggestions) for how to solve our own problems, we are able to hear the advice of prophets and scripture, and are willing to accept the grace of another, rather than rely on our own salvation check-lists.

A story that illustrates how Girard’s atonement might apply on the personal level occurs in C.S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce, in which the spirit of a deceased man visits heaven, ready to be welcomed in with open arms, only to find that the spirit who is sent to welcome him into heaven is the spirit of a man he knew on Earth, a man who was a murderer. In an escalating argument, the self-righteous soul eventually declares that he would “rather be damned than go along” with the soul of the forgiven murderer into heaven, and of course, in the end, he is.8 This story illustrates the consequences of rejecting the Girardian version of the Atonement. God has already saved us: He has already allowed the murderer in, forgiven his sin, and given him all; it is only the bitter spirit’s demand for vengeance and justice that keeps him from benefiting from the same gift. Framed in terms of the impossibility of something unclean entering heaven, under Girard’s theory, it isn’t God or Satan who would complain bitterly of the unclean entering heaven without a price being paid, it’s our fellow humans, who, in their clamoring for human justice, would leave everyone, including themselves, out of heaven.

Book of Mormon Soteriology

How do texts from the Book of Mormon fit with these various theories? By and large, they support an objective paradigm, that is, they support the theory that there is a real price to be paid, and that the Atonement is in some way a price paid to God. This shows up in numerous scriptures across the Book of Mormon. For instance, 2 Nephi 9:26 notes that the Atonement fulfills the demands of God’s “justice upon all those who have not the law given to them.” Similarly, Alma 12:32 states that “the works of justice could not be destroyed, according to the supreme goodness of God,” but of course, this justice is an aspect of God’s being, not another deity that must be appeased. Alma 42:15 is more explicit about the balancing between mercy and justice, both aspects of God’s personality or Godhood that must be appeased, stating “And now, the plan of mercy could not be brought about except an atonement should be made; therefore God himself atoneth for the sins of the world, to bring about the plan of mercy, to appease the demands of justice, that God might be a perfect, just God, and a merciful God also.” So, if there is a single atonement theory that is dominant in the Book of Mormon, it is the objective paradigm.

That said, there are intriguing hints of a second approach to the Atonement in the Book of Mormon that suggest the Girardian tale of cycle-breaking operates in the background of how Book of Mormon prophets thought about the Atonement. Perhaps the best single verse supporting this reading springs from Amulek’s sermon in Alma 34:13: “Therefore, it is expedient that there should be a great and last sacrifice, and then shall there be, or it is expedient there should be, a stop to the shedding of blood.” Of course, this bloodshed comes as a result of violation of the law (perhaps pointing towards an objective paradigm), but Amulek notes that it is “our law” (verse 11) that requires the shedding of blood, not God’s.

However, the Book of Mormon must also be read as a whole and not just proof-texted. More than any individual verse, the Book of Mormon covers a millennium of cycles of violence, highlighting the futility of spiritual self-help in bringing about the end of those cycles. Most readers of the Book of Mormon have observed the pride cycle, where increasing desires lead to increasing tensions, lead to violence, regret, and forced humility. This cycle matches Girard’s theory as well, as it emphasizes that we are not only unable to save ourselves with our own rightness or demands for justice—we condemn ourselves until only God’s grace can intervene. Beyond this, the Book of Mormon tends to litigate against spiritual self-help: the most successful prophets and leaders are those wise enough to trust in God, often without a plan to save themselves. For instance, the people of God were never able to win against the Gadianton robbers in offensive wars against their mountain strongholds, but they were successful when they trusted the Lord and allowed the robbers to come to them. Nephi and his brothers tried two plans to get the brass plates from Laban, before ultimately giving up and following the Spirit. The Anti-Nephi-Lehis, by refusing to fight the Lamanites and being struck down by them, ended up converting more people to the Church after their surrender and slaughter than before it. All these examples, and most likely many more, illustrate that, according to the Book of Mormon, it is not up to us to “save ourselves,” through clever plans, violence, or even self-defense. The Book of Mormon appears in many ways as an anti-spiritual self-help work. It calls on us to rely on the Lord’s saving power and work toward Zion. In this, the Book of Mormon bases the Atonement, at least in part, around a Girardian explanation.

Conclusion

What should we as members of the Church do with this knowledge? Should we embrace Girardian theory and stop talking about spiritual debt in our lessons, stop worrying about what prices are to be paid? Or should we follow the more prominent soteriological explanations of the Atonement in the Book of Mormon and think about God’s justice and mercy as we repent, and of the price that needs to be paid? Should we divide into camps favoring one theory or the other? Of course, a hopeful Saint might desire that we learn something from each camp, that “all the explanations are true,” or have truth in them. On the other hand, these explanations may also be mutually exclusive.

As is often true in such situations, turning to modern revelation can provide a partial answer, not by resolving the dilemma, but by recentering it. President Nelson has recently reminded us: “There is no amorphous entity called 'the Atonement' upon which we may call for succor, healing, forgiveness, or power. Jesus Christ is the source . . . The Savior’s atoning sacrifice—the central act of all human history—is best understood and appreciated when we expressly and clearly connect it to Him." In the end, Christ is salvation, and each atonement theory is merely a different way to understand him, his work, and the miracle of his grace.

Ben Dearden is a lawyer, a husband, and a father of two sons. He enjoys writing articles, screenplays, and stories with tiny audiences.

For an excellent summary of these theories and some of the implications, see Ben Pugh, Atonement Theories: A Way through the Maze (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co, 2015).

C. S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (London: HarperCollins, 2005).

See, e.g. Anselm, Cur Deus Homo, 1960.

For an early example of the direct opposition between objective and subjective theories, see Peter Abelard’s works countering his contemporary Anselm (cited above). See, e.g. Peter Abelard and Steven R. Cartwright, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2011).

Girard René, I See Satan Fall like Lightning (New York: Orbis Books, 2011), 10.

Another use of the term “cycle of violence” also fits this pattern well; experts on domestic violence often describe a cycle of a honeymoon period, rising tension, and an explosion in which the abuse occurs. Girard applies a similar cycle at a societal level, rather than the level of one family, and adds the explanation that mimetic desire is the fuel that keeps the cycle running.

S. Mark Heim, “Saved from Sacrifice: A Theology of the Cross,” in Saved from Sacrifice: A Theology of the Cross (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), xi.

Lewis, C.S., The Great Divorce (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1946).

Thank you for this educational and insightful article! I, too, am one who seeks to understand the “why” of everything, and this has long been a topic of great wonderment to me. I am not a scholar this field but have a few of my own thoughts.

Regarding the objective model, my understanding of “God” is that he/they are not original and that the nature of the universe/multiverse requires that God(s) operate in harmony with “laws” that God did not create, but that exist independently and naturally. I am certain that many of these laws are far beyond our current mortal comprehension. The atonement must be Gods’ (including Jesus Christ) way of using their divine power and knowledge to “let us in” without making us pay. In other words, thinking about the objective model, the atonement is not God adhering inflexibly to his own arbitrary rules, it is Gods giving us an incredibly loving and merciful pass through their own sacrifice and suffering to circumvent some natural, universal requirement.

I also wonder “Just what exactly did Jesus do?!” My favorite theory: during those moments in Gethsemane and on the cross, he entered some sort of time warp and actually experienced (lived with us) each one of our lives in its entirety. He is with me now and always has been. That is how he understands me completely. This obviously would have taken a long, long time - billions upon billions of years. This could explain such hesitation and fear expressed by a diety at the onset of the atonement.

For now, I have to ask myself - Is it enough for me to know that some sort of “law(s)” exist and that there must be an atonement to satisfy the law in order for the Great Plan to work? Can I still feel Christ’s redemption working for me without understanding why it is necessary? Just as a child doesn’t understand the why’s of cellular respiration and metabolic oxygen debt, but can feel the need to breath after a long underwater dive, and knows the relief of heavy breath after surfacing? This definitely requires faith and often feels unsatisfying. But I have hope that someday I will understand better.

Thank you! Better understanding these different theories really helps to focus on the Why. I don’t find it surprising at all that there are different or even conflicting explanations of something as incomprehensible as Christ’s atoning sacrifice. As Paul wrote, “For we know in part, and we prophesy in part.” I have another theory that I will call the Relationship theory. This understands agapic love as the pattern of reality, where agape is defined as a fore-giving love (unearned, non-transactional). In this theory God desires more than anything to be in agapic relationship with his children (hesed, eternal life) and the only way this is possible is to make us equal to Them (D&C 84:33-39, Romans 8:17). This required God to descend to our level so They can raise us to Theirs. The power of Godliness (agapic love) was completely manifest in Christ’s atoning sacrifice. We had to see it completely embodied and only through his grace can we become transformed and capable of receiving the gift of his agape (Moroni 7:48). And when we do, “…we shall be like him…” and we will be “one” (John 17:11).