Click above to read “Ballad 39A: Tam Lin,” collected by American folklorist Francis James Child (1825–1896).

When I first heard the story of Tam Lin, I fell in love with the ending. Tam Lin’s situation was hopeless: a slave to the faerie, destined to die. It couldn’t be worse, but then . . .

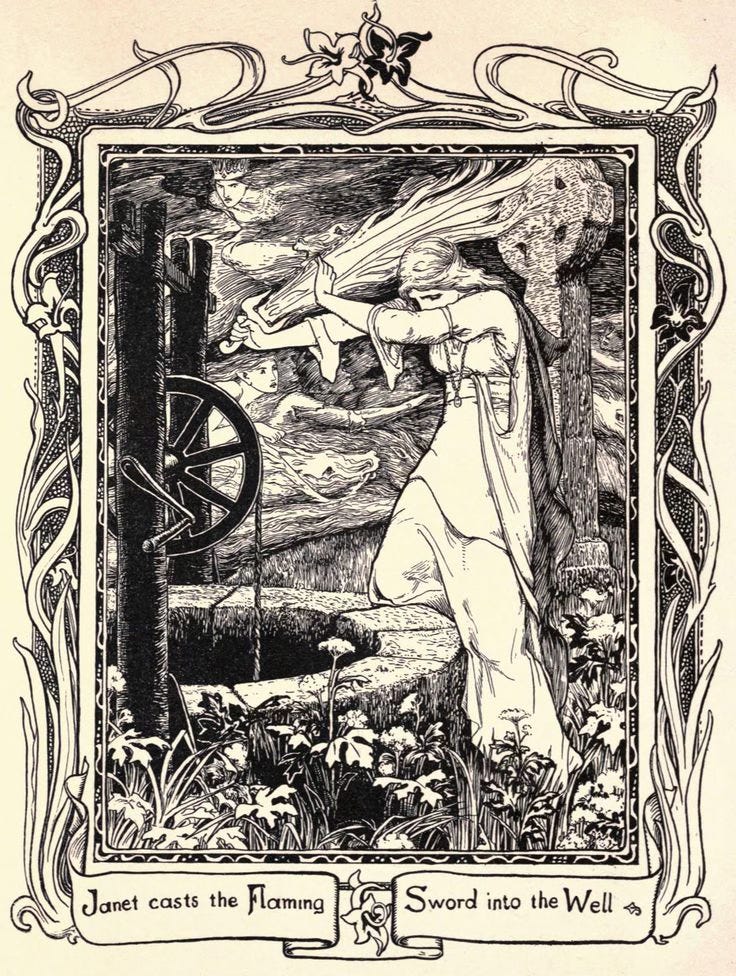

I was transfixed by the image of Janet, alone, nine months pregnant, dressed in her best green dress on Halloween night, pulling Tam Lin down from his milk-white steed as he was marched slowly to his death. As if that weren’t enough of a dramatic rescue, after pulling him down, she holds tightly to him as he turns into monsters in her arms—first a newt, then a snake, a bear, a lion, a red-hot rod of iron, and, lastly, a hot coal which she throws into the well. After all that, even the queen of the fairies agrees that Janet deserves her happy ending. As Tam Lin emerges naked from the well, Janet throws her green cloak over him, the bonniest knight in all the company, free at last.

Janet certainly loves Tam Lin (even though readers don’t always believe that he deserves it) and in the end, her steadfast love saves him. Her passion and commitment to his salvation cause her to put herself at risk, and sometimes readers are “confused at grace that so fully she proffers him.” And, in Tam Lin’s case, it isn’t a grace of restoration, justification, healing, or reconciliation. The force that saves him is Janet’s love.

But as much as I am attracted to the metaphor of love as a mechanism for Atonement, I have some issues with it—one being the small problem that the shape of the metaphor doesn’t match up with the patterns of the previous metaphors we have studied.

I have been using nouns to refer to these metaphors: restoration, justification, healing, and reconciliation. But they are also all active verbs; one can restore, justify, heal, and reconcile. In every metaphor so far, Christ’s role as Savior is to do something to us that makes us something new. That sounds complex, but it’s easier to write it out:

Christ restores us, and we are restored.

Christ justifies us, and we are justified.

Christ heals us, and we are healed.

Christ reconciles us to him, and we are reconciled to him.

But if Atonement is love, if what Christ does when he atones for us is to love us, then what are we having done to us?

Christ loves us, and we are loved?

This may make sense eternally, but with my limited understanding of love, I struggle to see how being loved equals atonement. The story of Janet and Tam Lin offers us a model of a love-driven atonement, as well as an alternative that deserves our careful attention:

Christ loves us, and we are reborn.

What is Love, Anyway?

Love is a powerful, soul-saving force that shows up in so many of our stories. An act of love can thaw a frozen heart; a mother who gives her life to protect her son from death can bestow upon him a lifetime of protection; true love’s kiss can turn a frog into a prince. Even outside of fairy stories, love is believed to have magical properties. The idea that love can bring miracles is ever-present in our imaginations.

Janet calls Tam Lin her “ain true-love.” And at the end of her story, she demonstrates just how strong her love is. We recognize her actions as actions of love, and on the surface, love seems like a concept we understand, a metaphor that should be fairly straightforward. It is something we are all familiar with, after all, and something that most of us aspire to give and receive.

The problem with using love as a metaphor for Atonement is that even though we all revere it, it is difficult to define what love is. Love seems to be as complicated to understand as Atonement. It is abstract. It is formless. According to scripture, Love and Atonement could even be the same thing. John says that “God is love” and dwells in those who love him (1 Jn. 4:8). Mormon writes that “charity is the pure love of Christ, and it endureth forever” (Moro. 7:47). These scriptures could both imply that love is the very essence of God and Atonement, that they are inseparable.

But we don’t usually talk about love like it is God. We often talk about it as a feeling of liking with more enthusiasm (I don’t like chocolate cake; I love chocolate cake). This definition of love is resonant with words like affection and attraction. But this meaning of love falls short in this metaphor. If love is a warm, fuzzy affection for something, how can we ever be expected to love our enemies? How can we even love our neighbors or ourselves? And if the greatest love is this, “that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13), is he feeling those warm, fuzzy feelings even in death?

Another definition of love is commitment. This definition is resonant in words like devotion and attachment. Love is always being there for someone. It is binding yourself to them. This resonates more fully with the idea of soul-saving love. A love that is unalterable, unfailing, indefatigable (the list could go on) feels more compatible with Atonement than a love that is merely a liking.

The difference may not be in the constancy of committed love as much as the agency. If love is a feeling, then we don’t choose it; we merely experience it when conditions are right. If love is commitment, then it is a choice. It is something that we decide we are going to do, an action of will.

There are many other ways we could define love, just as there are many ways to define Atonement. I have chosen these two because, in my experience, they are the most common lenses we use as we try to understand love. They are also both present in Janet as her story with Tam Lin unfolds.

Christ as Bridegroom

One relationship that is almost universally associated with love is that of the lover. And this is the first fairy tale we have read that includes a romantic—even physically intimate—relationship between the savior and the saved.

The metaphor of Christ as a romantic lover hasn’t received a lot of analysis within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but in the scriptures, Jesus Christ is often symbolized as the Bridegroom (Matt. 25:1–13, Mark 2:19–20). This is a powerful symbol of unity and love between Christ and his people, who are sometimes represented by wedding guests and sometimes represented by the bride herself (Isn’t the malleability of metaphors fun?).

A common reading of the Song of Solomon is that it is a spiritual allegory about the way Christ views his church, and oddly, many of the verses in this book feel like they could be pulled out of Janet and Tam Lin’s story directly. “Behold, thou art fair, my beloved, yea, pleasant: also our bed is green. The beams of our house are cedar, and our rafters of fir” (Song of Solomon 1:16–17). “My beloved is mine, and I am his: he feedeth among the lilies. Until the day break, and the shadows flee away, turn, my beloved, and be thou like a roe or a young hart upon the mountains of Bether” (2:16–17). The fairy world described in these verses feels almost dreamlike. And this allegory of Christ as a bridegroom and his people as his bride adds dimension to the comparison between Janet and Christ, and Tam Lin and Christ’s People.

As Janet’s story begins, almost the first thing she does is braid her hair, put on her finest clothes, and run off to Carterhaugh, where she knows she will find Tam Lin. After she becomes pregnant, when she has a chance to leave him for another (more stable and less liminal) man, she makes the conscious decision—moving from attraction to commitment—to hold on to him ‘til the end. Does Tam Lin deserve her? Not really. But neither do we deserve Christ, not as our bridegroom or in any other capacity.

Christ as Mother

A second relationship that is almost universally associated with love is that of the mother and her child.

In “Tam Lin,” Janet becomes pregnant, and by the end of the story, she is very close to giving birth. This part of her identity allows her to step into this second relationship and represent Christ as a mother.

Many scriptures call Christ our father (Ether 3:14, Alma 11:38–39), but in Matthew, the Savior uses the metaphor of a mother hen when discussing himself and his people, declaring that he wants to gather his “children together” (Matt. 23:37). Peter takes the metaphor further when he compares members of the church to “newborn babes,” who “desire the sincere milk of the word” (1 Pet. 2:2–3). The word is Christ, and when they taste of it, they find it to be good.

The metaphor of us as nursing babes, wholly reliant on our Savior, is both shocking and powerful. On one hand, the vehicle of the baby for each of us shows how truly helpless we are. Then, when looking at the vehicle of the nursing mother, it shows Christ’s complete and total commitment to our salvation. A nursing mother cannot leave her baby for longer than a few hours. She nurtures the baby with her body in a visceral way. It is in this way that Christ nurtures us.

Speaking messianically, Isaiah expands this lesson when he writes, “Can a woman forget her sucking child, that she should not have compassion on the son of her womb?” I remember the first time I read this scripture, thinking that Isaiah would equate Christ’s love with the love of a mother, but he continues, “Yea, they may forget, yet will I not forget thee. Behold, I have graven thee upon the palms of my hands” (Isa. 49:15–16). Reading this, I was gobsmacked. He wasn’t equating the two loves; he was placing Christ’s higher. In these short verses, Isaiah takes the holy, respected, even (for better or worse) idealized relationship of mother and child and then raises Christ’s love above it. A mother can birth you, he argues, but through Christ, you are reborn. Through his Atonement—the Atonement that left permanent scars on his hands and feet, that caused Christ to cry out to God in pain—he has shown a greater love than even that of your mother.

The Lord articulates and explains the metaphor of birth (vehicle) and rebirth (tenor) very patiently to Adam in Moses:

Inasmuch as ye were born into the world by water, and blood, and the spirit, which I have made, and so became of dust a living soul, even so ye must be born again into the kingdom of heaven, of water, and of the Spirit, and be cleansed by blood, even the blood of mine Only Begotten; that ye might be sanctified from all sin, and enjoy the words of eternal life in this world, and eternal life in the world to come, even immortal glory;

For by the water ye keep the commandment; by the Spirit ye are justified, and by the blood ye are sanctified. (Moses 6:59–60)

These verses gained new meaning for me after I gave birth to my first child. I experienced firsthand the birthing process, and while it was magical, it was not a sparkling rainbow tale full of roses and smiles. It was one of the fairy stories where monsters creep in dark forests, miracles come at a cost, and bargains are made but never broken. There was—as this scripture promised—water, blood, and spirit. The water broke first, and the spirit entered the world with my daughter. But the blood wasn’t hers. The blood was mine. And even more than a mother gives a part of herself to bring a child into the world, Christ gave his very life to enable our rebirth.

One more strange and possibly stochastic similarity between Janet’s story (which is, remember, a fairy story and not an allegory) and Christ’s reality is the moment when Janet wishes to be free from this awesome power of birth and creation. She visits Carterhaugh for a second time, early in her pregnancy, and pulls the poisoned rose, thinking it would be better to abort her baby than to go through with it. Tam Lin stops her, asking: “Why pu’s thou the rose, Janet,/Amang the groves sae green,/And a’ to kill the bonnie babe/That we gat us between?” And her answer is to ask him a question in return, “‘Oh tell me, tell me, Tam Lin,’ she says,/‘For’s sake that died on tree,/If eer ye was in holy chapel,/Or Christendom did see?” She basically asks him if he is Christian. His answer is no.

In the end, Janet’s desire to be free from the responsibilities of raising a child is understandable, especially when we consider that she might have to raise that child alone or with a man who is no more than a wild shade. Even Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane asked for the cup to be taken from him (Matt. 26:36–46), for the burden of rebirthing all of humanity to be lifted. But Christ went through with the Atonement, and Janet goes through with her pregnancy, and in the course of the story, even causes Tam Lin to be reborn.

The Atonement of Love

Janet is a lover, Janet is a mother, and Janet rescues Tam Lin from his curse and his execution through her active love.

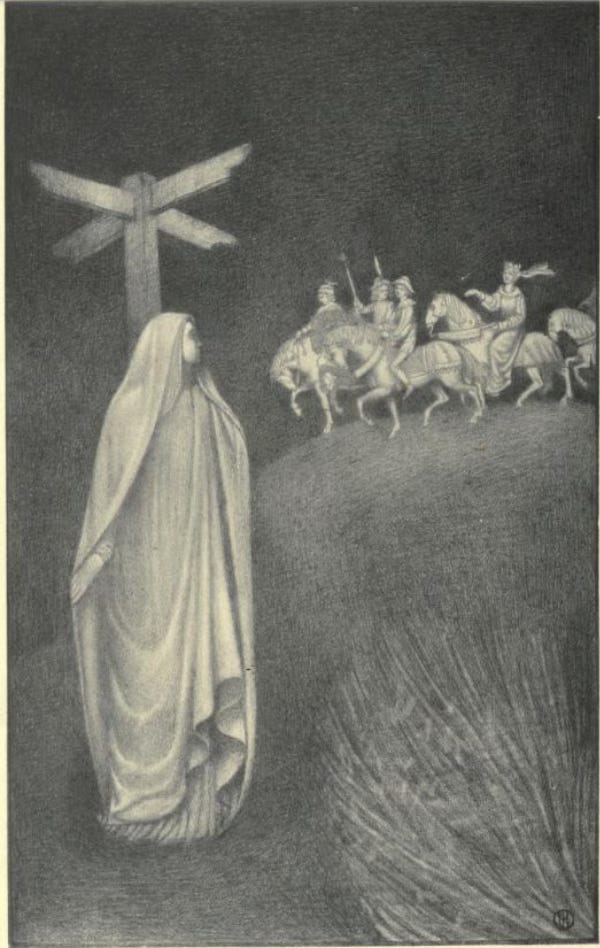

But if we are to use and understand this metaphor, we should seek to understand how love works as an atoning force. In Tam Lin, Janet asks her ain true love what she can do to rescue him, and his answer is clear. First, she has to recognize him and grab him. These tasks already prove difficult, but he instructs her to let the black horse pass and then the brown and pull him off the white. He tells her what he will wear and how he will do his hair. When she arrives on Hallows Eve, she is only able to recognize him as her own because he matches the description he gave earlier, even down to his one glove.

Then she has to hold on, a task more difficult even than grabbing him in the first place. The fairies turn Tam Lin into a snake, but she holds him fast and fears him not. Then they turn him into a bear and a lion, but she holds him fast and fears him not. Next, they turn Tam Lin into a red-hot rod of iron, but Janet holds him fast and fears him not, he having promised that he would do her no harm. And last, they turn him, still in her arms, into a hot coal (the burning gleed). She throws him into the well, a symbolic baptism, and he is finally transformed back into her love, the father of her child.

I am Tam Lin in this story. We all are. As hard as we may try, sometimes we are bears, sometimes snakes, and sometimes red-hot irons. But we have a Savior, and he has endless love for us. He is there through all of our transformations, standing beside us and hoping we will choose him. In his essay, “The Atonement of Love,” physician-scientist, ethicist, and theologian Samuel Brown says it well:

We are, unavoidably, painful to love. We are the infants who shriek through the night no matter how tenderly the parents try to soothe. We are the children who kick and steal and curse. We are the partners who betray, belittle, and violate. We are the narcissistic exhibitionists who can hear no voice but their own. And there God stands, through Jesus, loving us anyway. Loving every hard and painful bit of us. No matter how much it hurts God to do so. This is not the vacuous love that is indifferent to the shape of our lives as some pop psychologists might have it. God’s love will transform us: that is, after all, the end game for the Atonement. That transformation will be painful, and it is the best thing that could ever happen to us.

This metaphor, like the others, resonates with my experience. The Savior does for each of us what Janet did for Tam Lin: he holds us tight and fears us not. He descends from his throne to rescue our rebellious, proud souls. We are prone to wander, to leave him, but he never leaves us. He stays by us, understanding and loving us until we are ready to commit to him, then covenanting to be there for us even longer.

If Christ is our bridegroom, he takes us into his family and we become his beloved. And if he is our mother, we are begotten of him, born again in spirit. This kind of committed love is transformational. It changes each of us into a new person. Like Tam Lin was brought back into the world he came from, we are brought back into the presence of God, becoming someone new.

I love the final image of Tam Lin, emerging from the waters of the well, born again, ready to follow Janet back to civilization. Through her love, he was reborn.

Chanel Earl is a writer—mostly of fiction—who currently teaches writing at Brigham Young University.

Art by John D. Batten (1860-1932) in More English Fairy Tales, ed. Joseph Jacobs (1894); Katharine Pyle (1863-1938); William Cubitt Cooke (1866-1951) in Illustrated Popular British Ballads, Ancient and Modern, ed. R. Brimley Johnson (1894); J. Herbert Macnair (1868-1955); Katharine Cameron (1874-1965); John D. Batten (1860-1932); and Vernon Hill (1887-1972).

This is a beautifully woven metaphor. I love how you brought in Samuel Brown’s essay too, which is a favorite of mine.