What the Prophet Saw

Scripture as an Artistic Endeavor

What we look for influences what we are likely to find, and that is nowhere more true than in the context of scripture study. If you are like me, perhaps you have turned to scripture with the expectation of finding an answer to a question, or finding peace during tribulation. And those are understandable and worthy aims. Still, thinking about what we hope scripture will offer us begs some fundamental questions: What are scriptures, exactly, and how do we use them as we seek to connect with God?

I can see how my expectations about scripture change depending on my circumstances and mindset. At times I have found them useful as a sort of recipe book that teaches me how to follow a set of practices that will bring me closer to God. Other times I have read scripture as an inspirational guide that, in a holistic manner, helps me design and build my own life as a disciple. These modes of reading scripture share the common idea that scripture is intended to communicate immutable truths, and that the role of the prophets who penned them is to transcribe such truths to the best of their abilities. Accordingly, the ideal prophet would function as a transparent intermediary: God utters the words, so to speak, and the job of the prophet is simply to write them down. One friend of mine summarized this theory of scripture by saying that scripture (and general conference talks) are like “text messages from God.”

As appealing as this conception of scripture might be, further reflection—and my own limited experience with the ineffable—suggest that such a view might be misleading, or at least incomplete. Elements of our theology and history indicate that we have other ways to understand prophets and their words as found in scripture. I believe we need to grapple with the possibility that the creation and function of scripture do not work only as a divine communication transmission. In fact, understanding scripture only as “text messages from God” may needlessly limit the truths we glean from scripture precisely because that view limits the ways in which we can understand divine truth. In this essay, then, I want to ask: how else might we describe scripture, and what does it mean for our personal devotional practices?

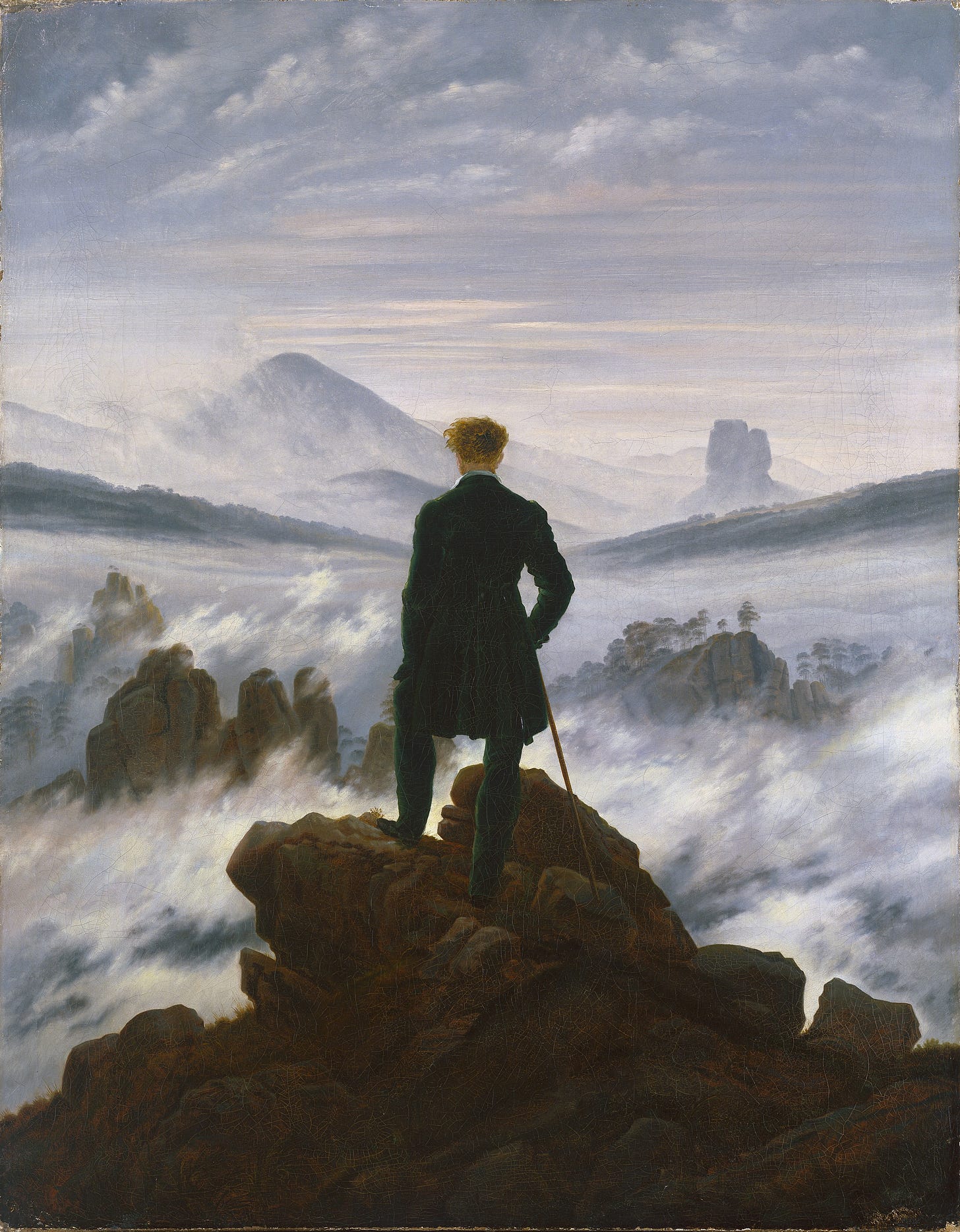

As I think along these lines, I am brought to think about one of my favorite paintings, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich:

This painting is considered one of the masterpieces of the German Romantic era, the quintessential Rückenfigur painting. This style of painting depicts its primary subject from the back, robbing us of the opportunity to see the figure’s face and thus focusing us on what the figure is experiencing. In the case of this painting, it brings our sight toward the landscape upon which the central figure gazes, sometimes seen as representing “the sublime.”

I love this painting as a metaphor for the prophetic project for multiple reasons. The first is that the painting pulls us away from the prophet himself and toward that to which the prophets point us—the sublime in the painting, Jesus Christ in our theology. Beyond that, the painting reminds me that prophets, too, are humans just like we are. The figure in the painting, though depicted in the foreground, remains dwarfed by the landscape he is beholding—he is not a titan, not a colossus, but a man faced with an overwhelming scene.

But the most important truth this painting suggests to me concerns what a prophet is and does, especially in relation to how we think about scripture. To me, the most powerful idea the painting conveys comes when I think about this question: “What would it be like if this man came back to me—assuming I had never looked upon the scene he is seeing and have never glimpsed this painting—and tried to explain to me what that landscape was like?”

Words would fail him.

They would not fail because he is not eloquent—Neal A. Maxwell and Jeffrey R. Holland, for example, are both quite eloquent, as are Alma, Paul, Isaiah, and Benjamin (and, for that matter, as are Kate Holbrook, Eliza R. Snow, and Melissa Inouye)—but rather because words simply cannot convey the full force and beauty of a scene like the one this man confronts. In some cases, this is a question of ineloquence (Moses’s “I am slow of speech, and of a slow tongue,” Ex. 4:10), but in other cases it is a testament to the categorical inadequacy of words to convey divine truth.

What strikes me about this is that prophets are deeply conscious of—and self-conscious about—this inadequacy. Indeed, their concerns about this limitation pervade scripture. I have already mentioned Moses. Likewise, it was Joseph Smith—that endless fount of revelations of every stripe—who lamented that English was a “little narrow prison almost as it were totel [sic] darkness of paper pen and ink and a crooked broken scattered and imperfect language.”

Similarly, this theme asserts itself insistently from the beginning to the end of the Book of Mormon. Nephi laments in his last eponymous chapter, “I, Nephi, cannot write all the things which were taught among my people; neither am I mighty in writing” (1 Ne. 33:1). And Moroni, who thought he was writing the compendium’s benediction and had almost closed (as he supposed) the entire record, intoned this stunning epigraph memorializing the limitations of both prophets and language: “Condemn me not because of mine imperfection, neither my father, because of his imperfection, neither them who have written before him; but rather give thanks unto God that he hath made manifest unto you our imperfections, that ye may learn to be more wise than we have been” (Morm. 9:31).

In other words, if I can add a bit of nonscriptural elaboration (including ideas found elsewhere in that same chapter), Moroni is saying, “God, I recognize that this record can never fully convey the weight of these ideas, but please let these imperfect words carry the beauty of the grace of Jesus to the hearts of those who will read them, and let those readers turn to Christ, who will bring to them the fully transcendent life these words never can.”

In this verse, I see Moroni envisioning himself (as it were) as the faceless figure in Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. He gazes out on the stunning expanse depicted in that painting—only infinite and even more beautiful—and then turns to God in desperation, asking, in effect, “How on earth am I ever supposed to convey even the thousandth part of that to other people by writing little squiggles on metal plates, never mind that those squiggles will then require multiple translations across time, culture, language, and space?”

The idea makes reason stare.

Reading Moroni’s words in this way, the prophetic and scriptural project moves beyond the idea of a person perfectly transmitting language that awaits in some heavenly vault. Such a conception, after all, could suggest something like prophetic perfection, implying that the prophet acts as divine medium for hallowed words, which further suggests that the words themselves almost require their own worship. Rather, scripture becomes something like a prophet’s artistic endeavor (even if most prophets do not see themselves as artists). I come to see a prophet as a person who is encountering the sacred and the ineffable in a visceral, personal, and immediate fashion and who is now tasked with communicating with us—in whatever way possible—the reality of that experience, and who will then invite us to have that experience for ourselves.

Let us look at Alma 5. This chapter can be read in more than one mode. We can read it as a set of best practices that leads us to happiness (it is often described as an “interview” we might have with ourselves). We can be inspired by its description of a disciple’s life. Or we can read it as an artistic expression of Alma’s transcendent experience with the power of the Atonement of Jesus Christ and the overwhelming moral suasion of that love. I don’t mean to suggest that one mode of reading this chapter is the “best,” “highest,” or “right” way. I value the insights I have gained from this chapter by reading in multiple modes.

Still, I did not feel like I really began to grasp what Alma might be getting at until I began to think of him as the faceless wanderer from the painting. Only, in this case, I believe he comes to us in that mode with a very specific message.

We have to remember that Alma spends his ministry haunted by the prospect of the hell he believed was yawning to swallow him up if he had not repented. Or, rather, the hell whose flames already arose to lick him when he realized the harm he had done during his wanton years. This is all to say: Alma 36 makes it clear, in Alma’s stunning poetry, that his central ministerial concern was to discover a language that could come close to conveying the full beauty, splendor, majesty, and transformative power of the divine love, saving grace, and Atonement of Jesus Christ.

Understood in this way, Alma’s sermon in chapter 5 becomes an attempt over and over and over again to convey what he clearly knows he cannot fully or adequately convey. He begins the chapter by describing the physical deliverance of the people from King Noah and then analogizes this to the spiritual deliverance all must seek at the hands of Jesus. As he reminds his listeners, “Were the bands of death broken, and the chains of hell which encircled them about, were they loosed? I say unto you, Yea, they were loosed, and their souls did expand, and they did sing redeeming love. And I say unto you that they are saved” (Alma 5:9).

This idea of deliverance and salvation will be the theme of the rest of the sermon—everything he says is his faltering attempt to convey a beauty whose full grandeur compels but forever eludes him. This is Alma staring out into the sublime—that faceless wanderer, again—and then looking inside himself and seeing there the beauty that has arisen from ashes. This is Alma saying, “I have seen salvation, and I am going to try—but fail—to use this sermon to tell you what it is like.”

Alma’s sermon is nearly childlike in its earnest and enthusiastic attempt to convey something he does not have the words to communicate, like a five-year-old left spitting and sputtering as she tries to explain a wonderful new taste or sensation. Alma tosses out words and comparisons and analogies at such a furious pace, and with such reckless literary abandon, it’s hard to keep up. The sermon is not only a doctrinal treatise but also the portrait of a poet wrestling mightily with the universe’s most sublime idea—the love of God. This chapter becomes poignant precisely because of Alma’s rhetorical inadequacy. He never succeeds in his poetic endeavor, but gosh doesn’t he just keep trying.

Alma asks, implicitly: What is it like to be rescued by Jesus?

The rest of his chapter is the answer:

It’s like being delivered from a wicked king!

No, wait, it’s like having manacles snapped in two!

No, wait, it’s like being born a second time!

No, wait, it’s like being given a second heart!

No, wait, it’s like being cleansed when you were dirty!

No, wait, it’s like learning to sing a new and transcendent song!

And on and on the list goes.

Even all of them together still fall short. Like the sublime landscape in the painting, the entire point is how wholly inadequate is a painting, much less any person’s attempt to describe a painting, to convey the full beauty and splendor of the love of God.

Seen in this way, the entire scriptural and prophetic project becomes an attempt by those who have been transformed by the alchemy of divine love to use scattered, broken, and imperfect words to invite all of us to experience with personal immediacy the gathered, whole, and perfect love of Jesus.

Tyler Johnson is a clinical associate professor of medicine and oncology at the Stanford University School of Medicine and an associate editor and columnist at Wayfare. To receive his column in your inbox, first subscribe to Wayfare, then under “manage subscription” select “On the Road to Jericho.”

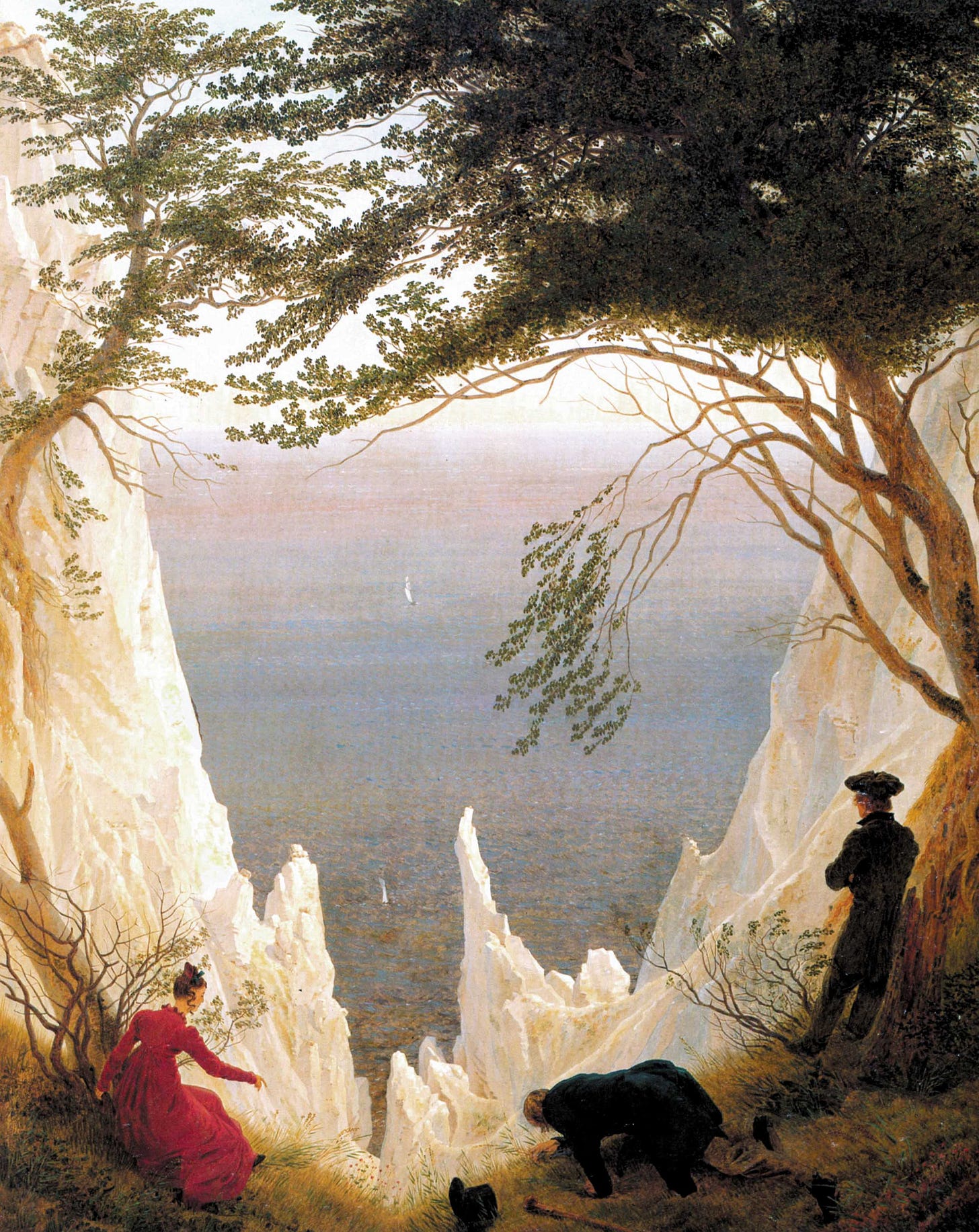

Art by Caspar David Friedrich.

KEEP READING

Brainsick

This essay is dedicated to those who must journey through what Elder Holland once called the “battered landscape of the soul,” and to those who, though not suffering from mental illness themselves, journey alongside those who do.

Thin Silence

In Good Faith podcast host Steven Kapp Perry speaks with BYU English professor Matthew Wickman about Divine Silence and how we can navigate the space between us and God.

Thank you. I deeply appreciate the perspective. I've been trying to find the right words for this, and I love the learning from the painting of the "Wanderer" that you shared. Thank you for that. I've often pictured this second estate as if we are all living underwater, and perhaps prophets are trying to help us see above the surface. This painting (for me) captures roughly the same concept, and it's also beautiful.

I often feel like we (and I definitely include myself) tend to proof-text scripture, focusing on specific wording when it supports our positions. But when the words don't fit my own bias or interpretation, I find myself wanting to explain it away by saying the prophet couldn't find the right words. I notice this most when I read scriptures about punishment or vengeance ("vengeance is mine"). But then, with passages like "love your enemies," I'm tempted to assume those are the exact words of God. The right answer is probably somewhere in between, with layers of context to consider. I find myself wondering how to avoid getting trapped in a mode where I'm focusing on specific text when I should be seeing conceptually, and vice versa. And, perhaps even more importantly, how do I best help others appreciate both the textual and conceptual approaches, without undermining their view of the role of a prophet?

Tyler, This was a moving statement about divine perspectivalism. For the Gods to see more, they need to have different perspectives. Looking at the Earth from the moon is truly awesome, but looking at trillions of galaxies is more awesome (I don't know about looking at Higgs Bosons), and looking into the eyes of your love is even more awesome. We need to see less to see more often. Thus sociality is the preferred divine condition (among Kolobians) that thrives on sharing different views/feelings/thoughts/experiences of sublimity, beauty, purposes and means, and contesting the highest and best with mutually persuasive delight (not envy). Thanks for this article. Randall