Uphill on the Yellow Brick Road

Covenants, Oz, and the Energy of Atomic Attraction

This is the third essay in the “Covenant Life” series, where we are exploring together why covenants matter and just what they mean and do. Please see Rising Together and My Side-by-Side God for the previous two essays.

I have always loved to sing, and ages ago I dabbled in acting. So, when I was asked if I would play The Wizard of Oz In an upcoming ward production, I accepted almost without thinking. I figured I would say some lines and maybe sing a song and that would be that.

What the director forgot to mention was that being in the ward musical would also mean participating in large-scale dance numbers, meaning that nearly every Wednesday night for three months I would find myself up on the rudimentary stage in our ward’s “cultural hall” practicing my box-step and trying desperately to figure out how to “shimmy“ in a way that would still leave my teenager with a pulse and regular respirations after his immediate mortification had worn off.

Now, I am generally patient and happy to be involved. But I draw the line at dancing, and that line becomes a wall between me and public dancing. In the long list of things I have no skill in, this ranks very close to the top. I won’t say I was conned into this project, but false advertising wouldn’t be far off the mark.

Take that dislike and trepidation and combine it with the fact that I have little free time between my demanding day job, parenting, and various side projects, and you’ll see why the prospect of showing up every week for three months to learn dance steps resulted in a certain amount of grumbling and eye rolling when I would see that rehearsal on my schedule squeezed in between cleaning up dinner and helping with homework.

Still, I had accepted the part and made a promise to be there, so I showed up. Together with about twenty other people, I studied the series of dance moves, watched the choreographer show us how to do each one in sequence, and then slowly worked to memorize them and to figure out how to get my feet to do something at least passably similar to the steps as they have been outlined.

Was it fun?

At first, not really. I often felt tired as I arrived and relentlessly thought about all of the other things that I could and maybe should be doing. As the hours and weeks passed, I recognized that being there was not just about dance steps. It was also about the conversations I would strike up with the person next to me as we both entered the hall, the chit chat between scenes, and the discussion I would linger for as the rehearsal ended. What's more, over time, either the steps themselves became less daunting, or I just came to take myself a little bit less seriously—or a little bit of both. By the day of the production, I found myself moderately excited about the performance itself, but mostly drawn to the other people involved.

The real jolt of revelation, though, came on the evening of the performance itself. I showed up at the hall and found the Wicked Witch being painted in green, the Tin Man being covered in silver, and Dorothy donning her ruby red shoes. Meanwhile, the young men and young women were putting on their flying monkey wings and the munchkins were dressing in garish clothing combinations while the set designer finished up the play’s only backdrop and the tech team reviewed every light cue.

These were people of dramatically different ages, wildly varying socioeconomic circumstances, diversified political opinions, and even deeply varied commitments to the institutional Church. As I stood against a sidewall and watched them all work together on a single performance of our amateur production of The Wizard of Oz, though, it became clear that I was watching community coalescing. Indeed, as that coalescing became clear, it was hard not to think of the intrepid and dauntless nonagenarian in that same ward who had directed just this type of community production—often stocked with participants who were initially much less enthusiastic than I had been—for nearly fifty years. It was like being able to see for a moment the formation of invisible connections between people—strands of trust, appreciation, and good will; as if I had become witness to the forging of friendships and the making of the mutual care that was drawing us together into a coherent mass of affection.

So, how does this relate to living a Covenant Life? To answer, I’ll draw on an analogy from the world of physical chemistry. I recognize the transition from ward musical rehearsals to atomic bonds may seem abrupt, but just stay with me for a moment and I’ll close the loop shortly.

In general, two atoms that are prepared to bond with one another want to do so because their bonded condition will be of “lower energy”—a state of affairs that nature almost always desires. But in the world of chemistry almost nothing is ever free, and so it is often the case that arriving at that more stable state of bondedness requires an initial energy investment, in the form of what we call the “activation energy.” Even two atoms that nature knows will be happier once bonded cannot get to that place unless some force offers enough energy to get the system over that initial hump.

My experience tells me that as it is with atoms in nature, so it is with people in life. One would think, after all, that all people everywhere would be rushing to form communities. Just about anyone who has ever belonged to a thriving community will tell you that such membership is priceless and blesses virtually every aspect of the lives of those included. What's more, significant research over many years suggests that by far the single most important factor in determining the happiness of a life is the strength and depth of the relationships that define it. Yet, in 2025 we decidedly do not see people rushing to build communities of any kind. Instead, community is becoming increasingly rare. For example—and for the first time—the Wall Street Journal’s recent annual survey of what matters most to Americans showed that we no longer even claim to care about community— in many cases, we seem to prefer to be alone.

Similarly, in one of the most striking articles I have read in many years, Derek Thompson outlines in his recent Atlantic cover story that we have mis-named the relevant problem. We often lament, he says, the epidemic of loneliness, and yet the actual problem is not that we are lonely but that we are not. Reams of data show that we are now more often alone than we used to be, and yet many of us no longer pine to be with others—we are alone and we like it that way. Perhaps it has simply become too easy to retreat to the private monasteries of a digital world. This, after all, is one of the most striking suggestions in Christine Rosen’s new book, The Extinction Of Experience. Rosen, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, uses the book to explore the myriad changes that the digital revolution has brought to modern life. The details of those changes lie beyond the scope of this essay, but one of her primary conclusions is that modernity may have rendered life too easy for too many of us in numerous ways. She argues that many of the transformations that have come to modern life accrue because we prefer ease by default and adopt related technologies without carefully analyzing their costs.

This brings us back to what Covenants have to do both with The Wizard of Oz specifically and with building community more generally. Many specific covenants within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints relate to building community. For example, either as part of or a result of the baptismal covenant, we promise to mourn with those who mourn and comfort those who stand in need of comfort—perhaps the most central bond comprising our church community. Beyond that, it is also true that we make covenants to sacrifice on behalf of others and to consecrate all that we have and are to building up God's Kingdom, which is to say to blessing, lifting, building, and supporting the people around us.

It's hard to identify the exact moment or level at which such covenants operate. I don't know precisely the instant at which a covenant starts to change what I do, let alone who I am. But perhaps covenants become operational just at the moment that we don't want them to. That is to say, my covenant becomes important when it's 7:20 on a Wednesday night and I am grumbling to myself about how I really don't want to head over to the church to learn a new dance step and I'm thinking to myself that I might just as well stay home and read. But I did make a commitment—a small-scale one to show up that night and a much larger one to consecrate all I have and am to the building up of the kingdom.

So, I go.

It seems like such a small thing—and, unavoidably, it is. After all, we’re talking about a single night of a campy play put on by earnest actors of varying levels of talent (never mind the dancing). But, of course, that’s the thing about the workings of the natural, and, I think, the divine world: there are only small things. Every structure we ever encounter is, after all, held together by subatomic attractions even as it is kept separate from all other things by subatomic repulsions. And just as chemical bonds are the adhesive that glues together the universe, even so might the power of covenant be the force that binds us together as communities in Christ.

Maybe I can put it like this: the force that binds us together may be love, but the wellspring that provides the needed activation energy to overcome our own apathy, our routines, our desires to do what comes naturally is our covenants. And because covenant is the force that draws me across the threshold into close enough proximity with my neighbors to allow the power of love to flourish, it seems an attractant whose importance is only growing as we enter into an age defined by our desire to be by ourselves.

Tyler Johnson is a medical oncologist and associate editor at Wayfare. To receive each new Tyler Johnson column by email, first subscribe to Wayfare and then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for “On the Road to Jericho.”

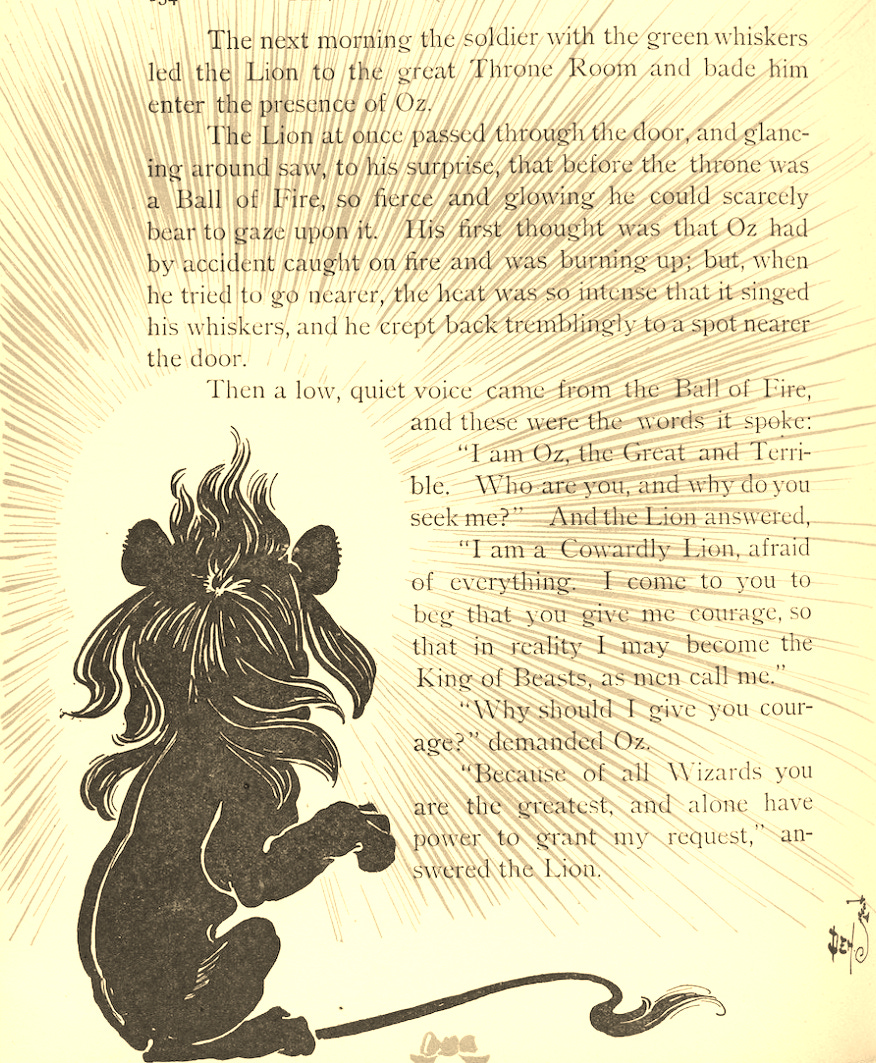

Art by W. W. Denslow.

Wonderful read. "There are only small things," that's something.

Great article; beautifully written and thought-provoking. Many thanks.