Tuned to the Covenant

How to Experience the World like Dogs and Birds

There is something about the story of Gideon and his men at the well of Harod that has long puzzled me. To recall, the Lord stood ready to deliver the camp of Midian only to confide in Gideon that he worried the troops would boast of their own strength in victory rather than recognize their dependence on him. So from 32,000 men, the soldiers were first culled to 10,000, and then in a second round to 300—an exiguous figure by most standards of warcraft, to be sure. And yet, despite the slender size of his force, Gideon was able to drive out the Midianite army.

As a literature professor, I can’t help but notice in the story a narrative urge to induce a sense of wonder at the miraculous power of God, to remind Gideon that “with God all things are possible” (Matt. 19:26, NIV). I mean, what sane person would look at an opposing army described as “thick as locusts” (Judg. 6:5, NRSV) and think a force of 300 soldiers sufficient to engage? As scriptural passages go, Judges 7 is an impressive hold-my-root-beer moment precisely because God’s ways are not ours, nor are ours his (see Isaiah 55:8). So the arithmetic logic of the story is by design; the culling of the soldiers is part of the plot. We read in anticipation of the outcome of their story, just as they must have waited—perhaps with anxious faith—for the Lord to reveal the wisdom of his strategy. When they vanquish the Midianites, their faith confirmed, the narrative tension resolves. Their success no doubt brought them relief; it also provides us the psychological closure so central to the structure of stories. Thus through the magic of narrative, we are made (or at least invited) to jointly, if not coincidentally, marvel with Gideon and his soldiers at the wisdom of the Lord’s curious and counterintuitive ways.

And yet, there is a detail in the story that remains cryptic despite playing an important narrative function. If Gideon was meant to understand that without God there was no hope, and if we as readers are meant to marvel at God’s ability to work mighty miracles with a less-than-mighty force, then why did God instruct Gideon to select those soldiers who “drank from cupped hands, lapping like dogs” instead of those who “got down on their knees to drink” (Judg. 7:5, NIV)? What is it about the knee-drinkers that disqualifies them, and what makes those who lap like dogs fit for Gideon’s force?

It wasn’t until I learned about the bi-hemispheric brain of birds that my confusion began to dissipate, replaced by greater light and knowledge. In his book The Master and His Emissary, Iain McGilchrist explains that the structure of a bird’s brain stems from “the necessity of attending to the world in two ways at once.” To simplify, a bird needs both to eat and to avoid being eaten. The former activity requires what McGilchrist calls focused attention; it allows the bird to find the kernel among the pebbles. The latter activity, by contrast, requires global attention, and allows the bird to stay vigilant to the threat posed by potential predators prowling for their own meal. Working in tandem, a bird’s left eye (and right brain) and right eye (and left brain) thus allow it to get on with the daily business of living—simultaneously attuned to that which will sustain its life and that which threatens to end it.

Humans, it turns out, are not so different from birds, at least as far as the structure of our brains is concerned. As with birds, our brains allow us to “attend to the world in two completely different ways, and in so doing to bring two different worlds into being.” What do these two worlds look like? In that of the right hemisphere, writes McGilchrist, “we experience—the live, complex, embodied, world of individual, always unique beings, forever in flux, a net of interdependencies, forming and reforming wholes, a world with which we are deeply connected.” But it’s hard to make sense of experience when it resembles Heraclitus’s river, so we need some way of “stepping outside the flow” of this world of experience, some way of processing it.

To do this, our brain creates a second world, one associated with the left hemisphere, in which “we ‘experience’ our experience in a special way: a ‘re-presented’ version of it, containing now static, separable, bounded, but essentially fragmented entities, grouped into classes, on which predictions can be based. This kind of attention isolates, fixes, and makes each thing explicit . . . In so doing it renders things inert, mechanical, lifeless.”

The 300 soldiers handpicked by the Lord to go against the Midianites were men of a particular sort. In cupping their hands and bringing the water from the well up to their mouths, they were able to remain vigilant of their surroundings (global attention) while still quenching their thirst (focused attention). By contrast, those who drank from their knees saw nothing but the water before their eyes.

I suppose if the Lord had been so disposed, he could have demonstrated his awesome power by picking the knee-drinkers. But he didn’t, and I’m inclined to discern in his discriminating preference a lesson about the type of people into which He’s trying to mold us. Most of us aren’t soldiers; our battles are more metaphorical than that of the Israelite force. Our task is nonetheless to cultivate the same sort of bifurcated attunement to the world as Gideon’s 300 men. But rather than remaining vigilant of the enemy while drinking water, we are to grow more attentive to the “always unique beings” who surround us—the almost eight billion people on the planet we call our brothers and sisters—ever more able, in the language of Alma and Paul, to mourn with them when their spirits flag and rejoice with them when they rejoice (see Alma 18:9, Rom. 12:15). In this way, we can become competent ministers of the new covenant, following in the footsteps of the ultimate Master (2 Cor. 3:6).

There is, however, a catch, or at least a complicating factor or two; for as involved as both hemispheres of our brains are in “everything human” (if, admittedly, to differing degrees), they are decidedly not created equal. The left hemisphere makes for “a wonderful servant, but a very poor master,” McGilchrist warns. And yet, in many ways, the emissary would like nothing more than to become the master, his behavior looking “suspiciously tyrannical.” By way of illustrating the left hemisphere’s “usurping force,” McGilchrist cites the map from Jorge Luis Borges’s story “On Exactitude in Science,” in which the cartographic art of an unspecified empire achieves “such Perfection” that imperial cartographers are able to produce a map with a 1:1 scale. In a world with such maps, the emissary would have us believe there is no more need for the world—indeed, that there is no world beyond his map.

In thinking about the way the left hemisphere makes sense of the world, I’m reminded of an experience I had while serving as elders quorum president in a small Spanish-language branch. As those who have served in small units know, the task of implementing the full program of the church—or sometimes just keeping the unit afloat—can feel daunting. Perhaps sensitive to this reality, in one of my monthly interviews with the stake president, I quipped that every time someone uttered the word goals in a church setting, a part of my soul died. He remained, if sympathetic, unmoved by my observation that the term never appears in scripture. Still, I wonder if there aren’t times when many of us feel less like saviors on Mt. Zion of actual people and more like imperial cartographers moving around meeples on a correlated map (see Obadiah 1:21). To borrow from Mark 2:27, were the programs of the church made for us, or were we made for them?

Prior to the creation of our aforementioned branch, I served as a bishopric counselor in the English-language ward. I only lasted a couple of years. By the end of my time, I was, as they say, dying on the vine. It wasn’t something I had anticipated—the acute bouts of anxiety, feelings of alienation from the very people I was supposed to serve, ideations of a different sort that stirred from a long slumber. At one point, I mentioned something to the other counselor, hiding the depth of my struggles behind an insouciant remark about our never-ending to-do list, the constant measurement of our efforts. He had two words for me: middle management.

In a sense, I suppose he was right. If, on a cosmic scale, “there is no space in the which there is no kingdom,” then perhaps there is no escaping the need for those who can perform emissarial functions. (D&C 88:37). For what it’s worth, the longer we have spent in the branch, the more I have come to appreciate both the spiritual gift of administration (cartography of a sort) and those who possess it. The same tasks that I had viewed with such consternation while part of a bishopric, I came to see in the branch as part of the skeleton that gives shape to the body of Christ. What a difference in outlook a change in circumstances can prompt.

As McGilchrist writes, “Attention is a moral act: it creates, brings aspects of things into being, but in doing so makes others recede. What a thing is depends on who is attending to it, and in what way.” It follows, then, that the world we inhabit depends to some degree on the mode of attention we pay to it. Maybe I became hyper-focused on those tasks of my calling in the bishopric that drew upon the left hemisphere. Maybe I neglected to reintegrate them into a holistic vision of why I was performing them in the first place, thus ignoring a right-hemisphere perspective. Even labor in the kingdom can feel like menial, mind-numbing busywork (middle management) without a proper appreciation of consecration, and maybe on occasion even with such appreciation.

Still, as vital as the work of the emissary is, left to his own devices, he would gladly play the role of pied piper, “sleepwalking his way into the abyss” and leading all who would follow. Citing the intrinsic asymmetry of the brain, McGilchrist implies that the master’s vulnerability to the emissary is very much by design, which raises the tantalizing question of whether we might not divine in that design some ulterior meaning or purpose, the way the author of Judges implicitly does in the case of Gideon and his 300.

Consider the fact that the emissary’s vision of the world dominates because the left hemisphere is “the controller of the ‘word’” (i.e., language). The emissary has a voice with which he can easily state his truth, whereas the truth that emerges from the “paradox and ambiguity” of the right hemisphere “is too complex” to be readily captured by language.

In the beginning was another Word, but this Word condescended to become flesh and, in doing so, became both Father and Son, Master and emissary (Mosiah 15:3). Christianity places the master and emissary in proper relation with each other. It is no surprise, then, that in looking for hope in our exceedingly emissarial age, McGilchrist turns to the body and religion, two targets of the left hemisphere’s “intemperate attacks” precisely because they constitute, along with art and nature, “the main routes to something beyond its power.”

Even as a nonbeliever, for McGilchrist, Christ as God incarnate is not “indifferent or alien” to his creation, but “on the contrary engaged, vulnerable because of that engagement” and “not resentful . . . about the Faustian fallings away of [his] creation, but suffering alongside it.” Given that “[t]here is no such thing as immaterial matter,” the incarnation of Christ explains why the Restoration insists that the power of godliness is manifest in embodied ordinances (D&C 131:7; 84:20). Only in the case of those who are temporarily disembodied do we find vicarious ordinances, but even these must be realized with an embodied substitute.

The power of the sacrament to resist the tyranny of the emissary became clear to me during the same period of my suffering service as a bishopric counselor. Sitting on the stand week after week, I began to notice how people would file in wearing their weekly worries and agitations on their faces, expressing it in their voices. Slowly, with the opening hymn and then the sacrament hymn and the passing of the emblems, I would watch as the spirit would speak peace to their souls, stilling the discordant notes of their hearts (Ps. 85:8). Some weeks the process took longer than others, but almost invariably, troubled hearts would be knit together in love and unity (Col. 2:2). It is hard to put into words what it is like to experience a miracle play out in real time; I can only say that I have witnessed the power of God unto salvation (Rom. 1:16). No doubt there were those for whom the miracle passed unnoticed, but for me those sacrament meetings were a welcome relief from the middle-management tasks of my calling, as necessary as those were.

Perhaps there is something about the nature and design of the church, and service therein, that embodies traits of both the master and the emissary. Others have certainly made this case. The prophet Joseph once observed, “God will feel after you and he will take hold of you, and wrench your heart strings, and if you cannot stand it you will not be fit for an inheritance in the Celestial Kingdom of God.”

In a very real sense, then, the covenant path that beckons is a path of covenant attunement. For Gideon’s men, it was bifurcated attunement to the enemy and the water; for me, the managerial tasks of a bishopric and the miracle of sacrament meeting. Whatever the specifics of the covenant path look like for us individually, to walk it is to walk in “that light [that] groweth brighter and brighter until the perfect day” (D&C 50:24). And what a day it will be! Not least because the sociality that we now enjoy will be coupled with eternal glory (D&C 130:2). The Pearl of Great Price gives us a glimpse of that future when it describes our reunion with the dwellers of the City of Enoch, when “they shall see us [and we them]; and [they] will fall upon [our] necks, and [we] shall fall upon [their] necks, and we will kiss each other” (Moses 7:63).

Such a vision is sweet to my soul—even if, on difficult days, I find the idea of Zion more appealing than the labor required to realize it. For until that day when “Zion is fled” heavenward, it remains a work in progress, a way station where it (which is to say, we) are under construction, working and waiting for the glorious day when we will be received up into the bosom of the Lord (Moses 7:69). When master and emissary will finally coexist with the same harmony that shall characterize the lamb and the lion when they lie down without any ire (Isa. 11:6).

Ryan A. Davis is a Hispanist at Illinois State University. He is interested in the life of the mind and matters of the soul.

Art by Paul Klee.

NEWS

Latter Day Histories is a three part lecture series from the Mormon History Association that features the latest research in Mormon history from award winning members of our community. On Thursday, October 24th from 7:00–8:30 pm, the first lecture will be delivered by Laurie Maffly-Kipp, titled “Mormonism in Asia: Soundings in Religious Globalization.” Afterwards, Michelle Graabek will join her for an interview, and moderated Q&A. You can read more about the event and register here.

Submissions are open for the forthcoming summer 2025 “Great Treasures of Gold: A Canadian Latter-day Saint Religious Art Exhibition.” Symbolizing not only the material wealth that Canada was prophesied to gather by Joseph Smith, as well as the spiritual and cultural riches amassed in over a century of Latter-day Saint presence in Canada, this exhibit celebrates the artistic tradition that has grown from Latter-day Saints in this land of refuge. Both professional and hobby artists who are Canadian or hold strong ties to Canada are invited to submit pieces for inclusion.

Deseret News writer Mariya Manzos explores the recent phenomenon of how Harvard Divinity School has become a hub for Latter-day Saint students studying religion. With ten current students, the cohort is the largest it has ever been, according to Harvard Divinity School faculty and staff. “Last year Brigham Young University was one of the top two schools in terms of sending students to Harvard Divinity. This year, BYU is the most represented.”

On October 19th from 4:00-5:30 Pm, Claremont Graduate University’s Mormon Studies program will host a special panel titled “Latter-day Saint Art: New Approaches” in celebration and discussion of the recent publication of Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader by Oxford University Press. It will be followed by an art exhibit opening reception, The Delicate Ties that Bind, from 6:00–9:00 p.m., showcasing many artists emerging from the Mormon tradition.

Wayfare extends a special congratulations to Zachary Hutchins, Professor of English at Colorado State University, for the forthcoming publication of his epic poem about the First Vision and the earliest days of The Church of Jesus Christ by University of Illinois Press. Set for release in Fall 2025, Joseph: An Epic represents twenty years of labor and promises to capture the origins of the Restoration as you’ve never heard it before.

Doorkeeping at the Temple of the Mind

Every idea, thought, fact or insight that traverses the stage of our consciousness changes us. Literally, physically. Neural networks in our brain rearrange themselves in adapting to the new information. With eighty-six billion neurons and one thousand trillion connections, a whole lot of architectural rearranging is constantly taking place in our brain…

Days of Awe

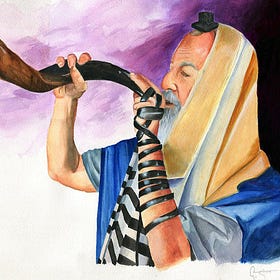

One September afternoon while washing dishes, I noticed an unusual baying sound coming from outside. At first I dismissed it as a passing animal or vehicle, but it sounded repeatedly, and I started to notice musical patterns. I realized it was the blowing of a Jewish shofar, or ram’s horn, part of the Rosh Hashanah services at one of the synagogues in m…

Our Lady of Seedlings in the Old-Growth

Mother trees [ . . . ] nurture their young, the ones growing in the understory. —Suzanne Simard