Trials of a Bad Spellor

Beyond the Shadow of Judgment

Picture a small sixth-grade boy standing hopefully, expectantly, against a classroom wall. His classmates are lined shoulder to shoulder, faces forward, anticipation and determination garnishing their eager faces. A list of words is proffered down the line, one to each child, who, in turn, must spell back the word in clearly enunciated English. The words are easy at first. In the first pass, none are expected to be asked to sit down. The first group of words is part of the “confidence-building” round. But as the first-round word reaches our young man, he stammers a bit, trying hard, but it is to no avail. He cannot spell it. He is asked to sit. He sits alone for four more passes through every child in the line before the next person joins him at the lonely desks. It is a spelling bee, and our little scholar is always first down, a reminder that he is lacking some aspect of normalcy—he knows he is endowed with a deep flaw that he does not share with his peers.

Alas, the boy is me. I admit this in hopes that my story will inspire others who lack this basic human skill, or perhaps teach such. To be a nonspeller in a spelling world is a hard thing. But you need more context. A few more incidents will set the stage for this blight upon my character, but there are some things you must know before I lead you into the depths of my disgrace. First, you must understand that I read voraciously. I always have. By eighth grade, I was reading at a college sophomore level. Second, I love poetry and love to write. A common enough desire, but combine that avocation with a lack of capacity in spelling—that most basic technical skill at the heart of the writing enterprise—and it becomes a tale of tragedy. Or dark comedy, if you are the kind of person who found Hardy’s Jude the Obscure farcical with its depiction of a poor young man trying to break into the stodgy world of a nineteenth-century British university. For not a few have openly questioned, when confronted with my scribblings, whether I have any facility with written English at all. As an employer said to my father in my senior year of high school, “He is, in fact, functionally illiterate.”

There is something monstrous about being different. Let's call it “Unbelonging.” A neologism fashioned to capture that sense that one is separate and apart. A flawed thing. Present, but apart. Perhaps uncategorizable. Perhaps shunned. Alone in the presence of others in whatever world they find themselves.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a nice place to start looking at what I mean. You need to remember the novel, however. The visual image of the monster that usually comes to mind when Shelley is invoked is the stiff-jointed, flat-topped giant of the 1931 James Whale film, in which the creature is brutish, inhuman, and dimwitted. The creature of the nineteenth-century novel is much different and worth a closer look.

The unnamed creature is thrown into existence as a mélange of decaying human remnants, forming a twisted mereology of embodied mortality. He comes into existence fully conscious but uncertain about what he is and where he fits into the ordered “chain of being” in which he finds himself. It does not take long to learn that he is a horror, despised for the appearance he presents to the world. And which he cannot help.

College freshman English. Our first paper is due. I work hard and turn it in. A friend helps me get the spelling right. Shortly after that, our papers are turned back. All except mine. Lark, my beautiful and elegant graduate student teacher, tells me curtly that I should see her after class. We retreat to her office. I was in love with Lark. We were the same age because I spent time in the army after high school and was, therefore, older than most first-year students. I fancied as I listened, moon-eyed, to her lectures, that in some preexistent state, we must have made certain promises to find one another in this life. It was clear we were meant to be together. Should I ask her out now? She holds up my paper: “I think you plagiarized this.” I step back. “Do you know what plagiarism means?” Did she just say that slowly, like you would to a dim child? “No, I didn't. I wrote every word,” I say. She smirks skeptically, like the Grinch. “I’ve seen your in-class essays. You can’t write like this.” (And it is true, all my in-class essays were returned with loads of the same red circles that many teachers in my life were and will be fond of.) I tell her, “Admittedly, I can't spell. That's all.” She says, “If that's true, where did you learn to write like this?”

I'm reaching for anything to redeem myself, and so in desperation, I challenge her, “I’ve read more books than you have.” It is a weak attempt at a stall, but we start a “Have you read this?” contest. It soon becomes apparent that I am not only well read but can hold my own in discussing content and ideas. She finally believes I wrote the piece but decides I need help, and maternally she tells me to enroll in remedial spelling. A 099 level class designed to make up for high school deficiencies. I thank her. I don't ask her out, mostly because I feel unworthy. Flawed. The piece was later submitted to a radio writing contest. I won first place and a fifty-dollar gift certificate to Provo, Utah’s finest restaurant. Lark could have shared that meal if things had played out differently. Alas.

The monster and Dr. Frankenstein meet for the first time in the countryside. The monster is miserable and angry: “Everywhere I see bliss from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend.” He begs for help: “Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.” Frankenstein, an early archetype of the mad scientist, abandoned his creation in a bout of sickness over what he had created. But here they meet again.

The hideous thing tells his creator its story. It wandered for a time, and slowly, its consciousness became more attuned to the sensations and content of the world. It finds a cozy hovel connected to a rustic cottage in which it can hole up. There, “it” becomes a “he” as he slides into personhood. He makes the little cellar comfortable and tries to figure out where he belongs in the world. A family lives adjacent to his abode. Through listening to their conversations and attending to their habits and concerns, he starts to experience curiosity about the world and pleasure in human company. He helps them discreetly by bringing food or helping to cut the firewood, but he remains hidden from their view, becoming ever more intimate with their history and burdens. He also learns about kindness. He describes how the family gave up their food for the blind old man that lives with them, “This trait of kindness moved me sensibly. I had been accustomed, during the night, to steal a part of their store for my own consumption; but when I found that in doing this I inflicted pain on the cottagers, I abstained, and satisfied myself with berries.” He learns to read (with a penchant for Plutarch) and begins to long to become a part of this small group of people he has come to care for. He wants to reveal himself.

I take the spelling class. Under its aegis, I go from about a sixth-grade spelling level to an eighth- or ninth-grade level. It is a triumph. Of sorts. At the same time as I am plugging away at the most common misspelled words in the English language, however, tech gurus are inventing WordPerfect—and the spell checker—a prosthetic device that will change my life. Freed at last from the need to pass everything I write to indulgent friends, I can at last make my move. I decide to major in English. A dream come true for the kid from Moab, Utah. A win in the university’s undergraduate short-story contest has emboldened me. I am feeling daring and empowered. With WordPerfect, no one need ever know my secret shame.

I enroll in a class on English literature prior to 1600 AD. I decide to bypass all the 200-level classes because I’ve read everything on their lists. The class is mind-blowing, and I am in heaven as we read Piers the Plowman, Canterbury Tales, The Song of Roland. I can’t get enough. I am happier than I have ever been. In class, I am Hermione Grangeresque—my hand waving in the air at every opportunity. Then it happens. Our first test is an in-class examination. Blue books. The request that we bring those little stapled notebooks means an essay test. And this would be closed book.

I show up feeling melancholy and afraid. I’m about to be exposed as a fraud, a pretentious charlatan. But who knows? Maybe the teacher will just dock me a few points, and I'll still be fine. I tell myself this over and over. The test comes back after about a week. I've been somewhat subdued in class lately, afraid of what the future holds. I open the exam, hoping for the best, but there are markings everywhere, like some postmodern art called red circles and blue lines. I’ve flunked. No comment on the content of my writing—only red circles with little “-1s” beside them, each one removing a point from my starting 100. By the end of the exam, I am well into negative numbers. I sit silently through the remainder of class, blinking away the tears trying to escape my eyes. I cannot major in English. I drop the class and the major and wander in darkness for a time, ending finally in that gang of ruffians and ne’er-do-wells who care not a whit about your spelling, as long as you show some flash with a calculator and know how to handle the probabilities: statistics. An unsavory lot, yes, but we take what company we can get.

The monster plans his next move carefully. He longs to be a part of the life lived among those in the cottage. He has high hopes. He tells Frankenstein about the pain of his isolation in the hovel where he lives this vicarious life and reveals his plan: “These were the reflections of my hours of despondency and solitude; but when I contemplated the virtues of the cottagers, their amiable and benevolent dispositions, I persuaded myself that when they should become acquainted with my admirations of their virtues, they would compassionate me, and overlook my deformity. Could they turn from their door one, however monstrous, who solicited their compassion and friendship?” Will the villagers see past his hideousness? Can they forget his grotesque and dreadful appearance? Of course. Of course they can.

I discover the subject of ecology and evolution in biology classes, and I start to frame an idea of doing quantitative and evolutionary ecology. Clearly, my days of literature are over. I could not even hear the word “English major” without cringing. I dated one once (an English major, not a “word”), but as with Lark, I felt unworthy in her presence. The relationship could not be sustained—what if she found out about my spelling? If we married, would my refrigerator love notes be covered in red circles?

Well, word processors kept me hidden for the most part. I was discovered from time to time, to my harm and embarrassment, as happened once at UNC–Chapel Hill in my biostatistics program when my Wetlands Ecology professor passed out an in-class essay test. You know what’s coming. It was returned with the shaming circles of red branding and highlighting my damnation. He wrote on my paper, “You can’t spell. See me!” He was horrified. He told me my problem had its roots in the lack of Greek and Latin in school curricula today. To him, I became a symbol for all that’s wrong with twentieth-century education.

Once again, I was reduced to the single dimension of my most significant character flaw. I quit raising my hand in class and started sitting in the back. I quit caring about making an impression and became aloof, cavalier, and supercilious. When he asked for a one-page technical write-up on a wetlands excursion to a nearby lake we had taken, I wrote a four-page narrative poem in iambic pentameter, rhyming words like “zone one census” and “Impatiens capensis.” He wrote on my paper, “Interesting format. This will do nothing for your career.” Sadly, I had asked him before the “spelling incident” to be a recommender for my PhD applications to biology graduate programs. Unfortunately, he sent the letters after my exposure as a base-minded scrub. I was accepted to nary a program, despite prior phone calls to my proposed dissertation advisors, who had been enthusiastic when they had only my CV to go on. Something about my letters of recommendation had changed their minds. There was no doubt who sank me and why.

But in math, who cares about spelling? I was free of misjudgment, and math came easily to me. A bunch of rules and recipes. So I decided to go for a doctorate in biomathematics. Math became a healing drug; Functional Analysis, a way to drown the sorrow of failure; proofs, a narcotic for despair. But still, I was bitter, and in secret, late at night, I wrote novels that no one would read and wrote bête noire poems that piled up like scattered Styrofoam containers blown against the cold galvanized steel of a chain-link fence surrounding an inner-city McDonald’s. At Christmas each year, I would join in singing with passion, gusto, and pathos the song “We're on the Island of Misfit Toys” as I watched Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer with my children. At the appropriate point, I would add to the list of islanders—Charlie-in-the-box, train with square wheels, cowboy riding an ostrich—“a writer who can’t spell.” Sigh.

The human-made monstrosity decides that he will appeal to the blind old man first while the others are away. Without the ability of the grandfather’s eyes to fall on the horrifically dreadful aspects of the poor creature’s countenance, perhaps, he imagines, he can slip into his amicable graces without frightening him too much. He enters the cottage by invitation and presents his story and longing to the older man, who bends with kindness towards the miscreation. Just then the sound of footsteps announce the return of the others. He grabs the knees of the old man and begs for protection. The monster describes the events thus: “At that instant the cottage door was opened, and Felix, Safie, and Agatha entered. Who can describe their horror and consternation on beholding me?” Pandemonium follows. The monster is driven violently from the cottage with a stick like a rabid beast. He knows he could destroy his assailants, but he rushes out and returns to his hovel.

The family, who has fled in fear, abandons the cottage permanently. The monster describes the effect on him: “My protectors had departed and had broken the only link that held me to the world. For the first time the feelings of revenge and hatred filled my bosom and I did not strive to control them; but allowing myself to be borne away by the stream, I bent my mind towards injury and death.”

And thus, he becomes the monster of a more familiar mien. Unbelonging. A kind of monster maker. The family could not see beyond what was manifest immediately before them. The surface had become the substance and created anew the substance of their fear ex nihilo. The maligned beast would never escape the immediacy of the label that was thrust upon him and that, in the end, became him.

So there you have it. It is only a sketch of my walk as a nonspeller. I'm now a biology professor. I've largely hidden this affliction, but even today, I'm hesitant to write anything on the whiteboard or to put up anything spontaneously that hasn't been vetted through PowerPoint. I can only give a cursory outline of the significant events that amount to thousands of such incidences, losses, and costs. It is a cautionary tale of sorts about the hardness of the world and the snatching of dreams. I don't know why I can’t spell or even learn to spell, but if you have critiqued or peer-reviewed any of my papers, you’ve seen it often enough. I will read and reread things, but the misspellings are invisible to me. My brain reads them as correct, no matter how perverted the spelling. Something deeply embedded in my neurology, still in place despite years of trying to fix it, is strange and disheartening and speaks of a cold determinism for some things in this world.

Even so, I'm glad to share my shame—if only to convince a few of you to look more closely at that student who seems incorrigibly careless about spelling. Sure, circle a few words just to show you care, but then focus on what delights might be hiding underneath her tortured salad of symbols. She is not a monster. Maybe she just isn’t stitched together quite the right way, and perhaps you can keep her from becoming the maligned creature that the more superficial among us read her to be.

Steven L. Peck is an Associate Professor of Biology at Brigham Young University and the author of A Short Stay in Hell and Heike’s Void.

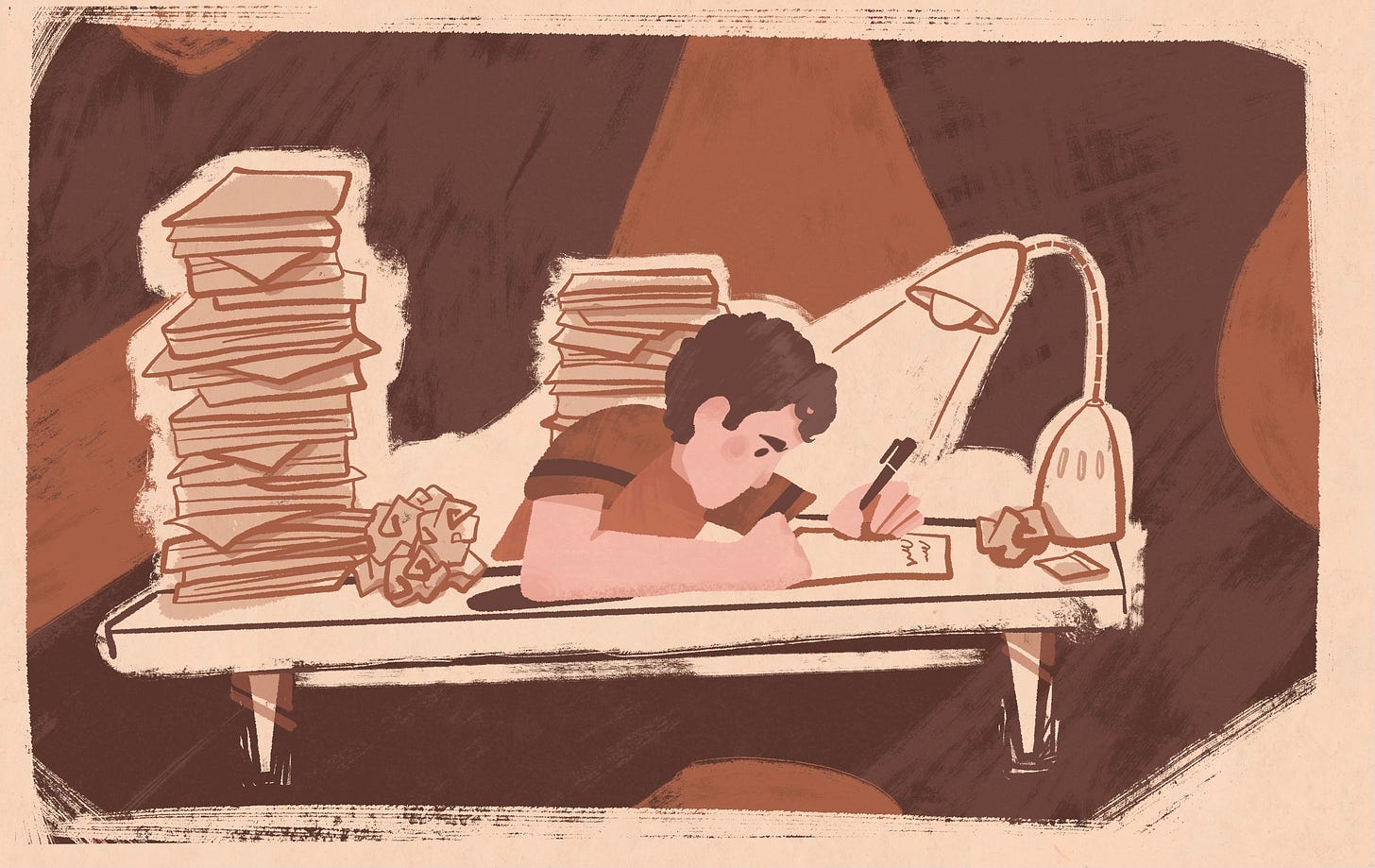

Art by Anna Wright.

JOIN US

Mother Tree Author Talk & Book Discussion

Join us on May9, 2025, at 12 PM MDT for a discussion of the power of the Divine Feminine as we conclude our reading of The Mother Tree. Author Kathryn Knight Sonntag will share her thoughts on the increased relevance of her book in our current cultural moment. Participants will be able to offer their own insights and raise questions about the themes of …

The Wayfare Festival 2025

Join Wayfare for our second annual summer festival. This year’s gathering features Adam Miller, Terryl Givens, Kathryn Knight Sonntag, Esther Candari, James Goldberg and many more.

KEEP READING

How Mormonism Sees the World

As part of the ongoing How to Think Politically series, Wayfare Magazine is pleased to host Nate Oman’s essay of popular philosophy “The Disposition of Mormonism” together with a forum of brief responses from signal thinkers such as Peter Conti-Brown (University of Pennsylvania), Greer Cordner (Boston), Samuel Moyn (Yale), Katharina Paxman (BYU), John D…

Never Get Used to This

Two summers ago, on a hike near Provo’s Khyv Peak, my friend turned to me and asked if I thought we would be able to see the Taj Mahal during the Millenium—if our exalted bodies could instantaneously transport us to see sites of wonder across the world. As I stumbled down the grassy trail, pines on all sides, I considered. Would mortal wonders even comp…

Companions in Faith

In Episode 94 of In Good Faith, Steve speaks with Reverend Andrew Teal, an Anglican reverend who works to build friendly, trusting relationships between different religions. A chaplain, fellow, and lecturer in theology at Pembroke College, Reverend Teal specializes in interfaith dialogue and frontier spirituality.

Latter-day Saint Art Episode 8: Film Studies

Jenny Champoux: Welcome back to Latter-day Saint Art, a limited series podcast from Wayfare Magazine. I'm your host, Jenny Champoux in Latter-day Saint Art, I'll guide you through an examination of the artistic tradition of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Each guest is a contributor to the new book,