Tokens of Meaning

Root Beer, Sea Glass, and Rosaries

Faith of our [mothers], we will strive, To win all nations unto thee, And thru the truth that comes from God, Mankind shall then be truly free. Faith of our [mothers], holy faith, We will be true to thee till death! —Hymns, no. 84

When I was sixteen, my Grandma Jean died in our home, cancer riddling her frail body. Father Michael from Saint Catherine’s down the street performed her last rites in my childhood bedroom. Our faiths were not the same, yet Grandma’s unwavering belief laid the foundation for my own. Her religious understanding, and that of my Catholic foremothers, introduced me to a rich and visual world full of symbolism, rites, tradition, and ritual that served as a backdrop to my own Latter-day Saint faith. Participating in my grandmother’s religious heritage not only developed our shared conviction in Christ but informed my understanding of women’s place in the sacred.

As a young girl, I would visit Grandma Jean in Chesterton, an hour's drive and a world away from our home in Chicago. Every summer, my Sunday visits to her small town in the shadows of the Indiana dunes involved three things: the A&W root beer stand, beachcombing, and Mass at Saint Pat’s. Each stop was essential to the tradition and never separated. All three parts of the excursion transported this Mormon city girl to a mystical haven, with Grandma as guide leading the way.

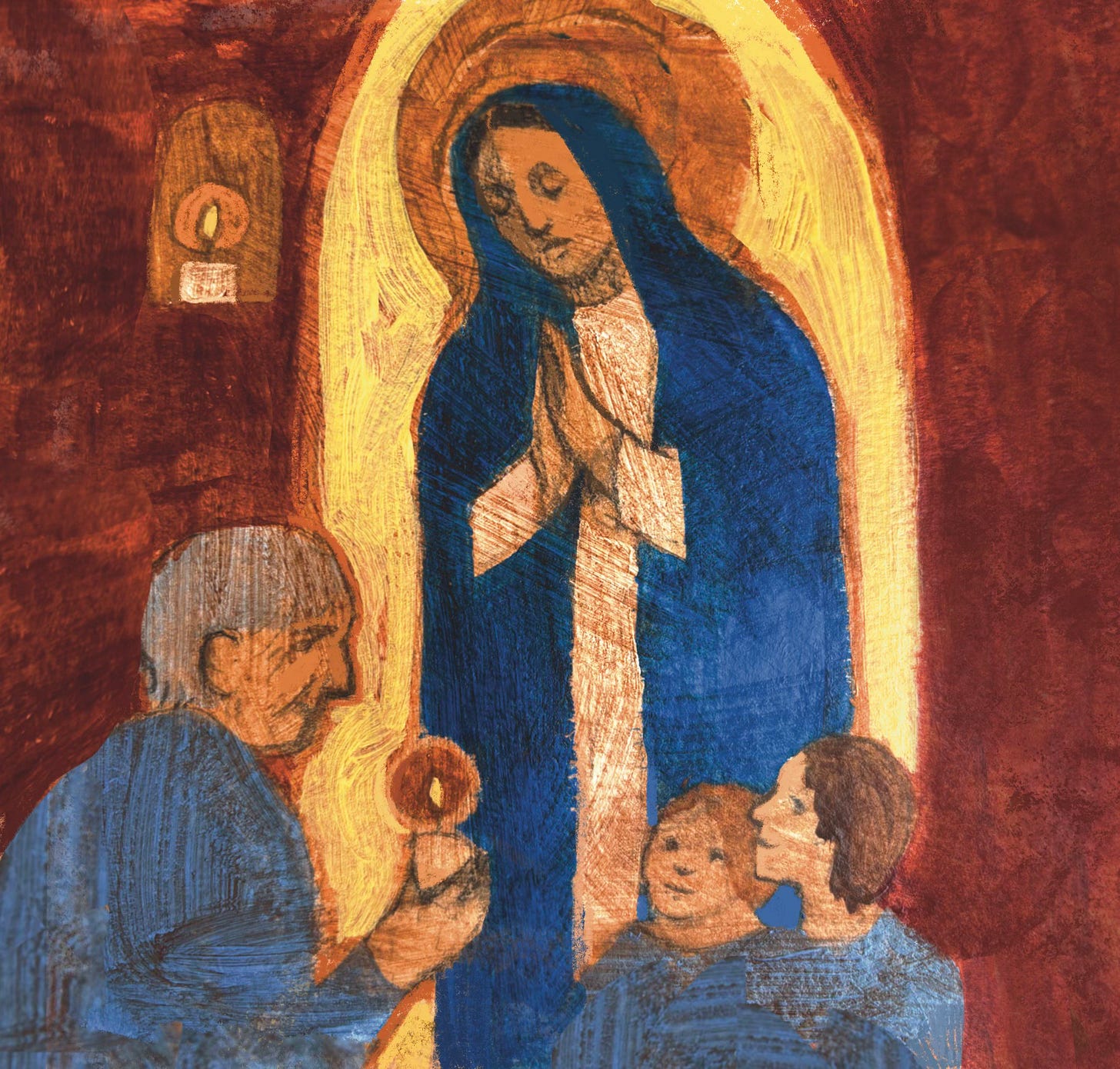

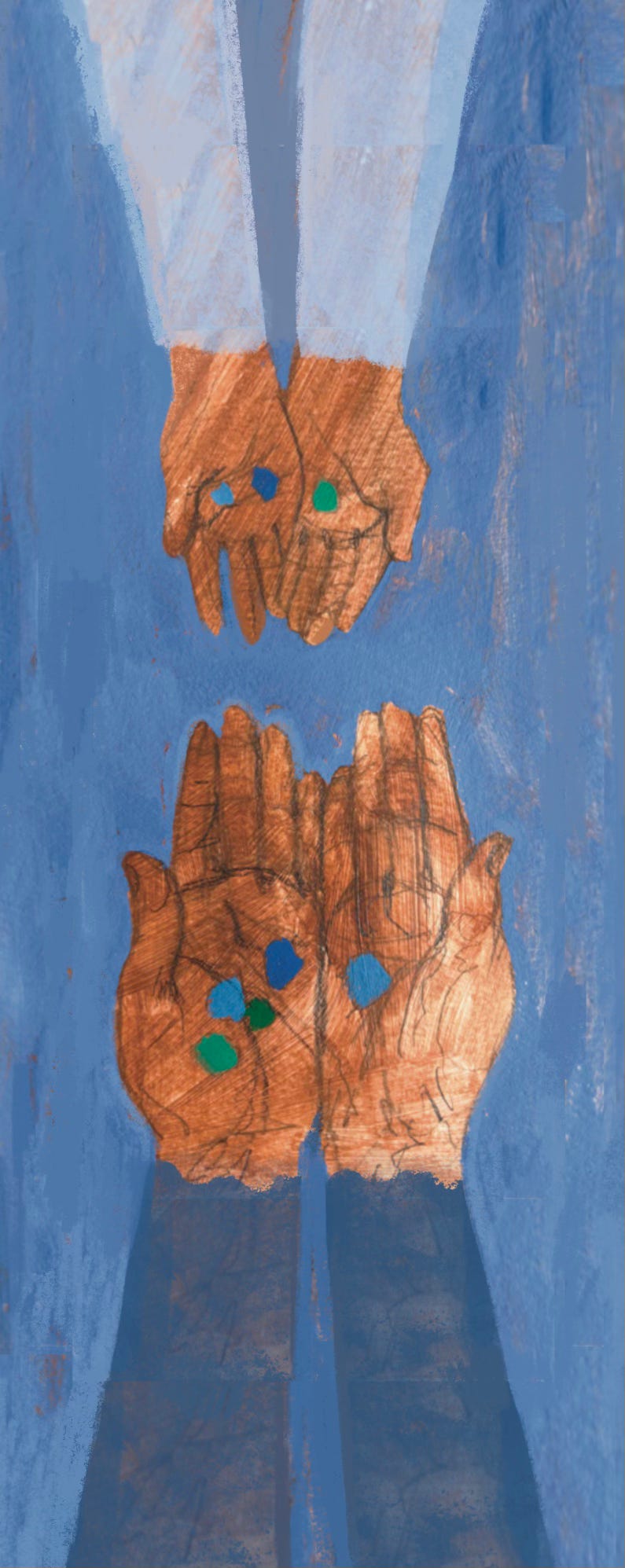

Frosty mugs and french fries delivered by roller-skating carhops, perfectly balanced on the precarious window tray hanging off Grandma's Mustang—magical. The soft, shushing corduroy sound of bare feet brushing through sand, backs warmed by the setting sun, eyes scanning the wave line in search of our tumbled green sea glass treasure—enchanting. The soft clicking of Grandma’s robin’s-egg-blue rosary beads, a fragrant whisper of ancient woods and spice wafting over us, the morning Sunday sun dancing through stained glass windows, Mother Mary front and center tenderly cradling the Christ child—otherworldly.

Although I didn’t see it at the time, Grandma created for us a sacred ritual with the cool caramel taste of root beer, the slow, joyful work of seeking tiny treasures, and the gentle rhythm of rosary beads sliding through her reverent fingers. In root beer, I learned that I am loved, that happy times together bond us, that a little sweetness makes things better. In sea glass, I saw that broken things can become new and beautiful, that letting our rough edges smooth isn’t something to be avoided, and that beautiful discoveries are there to be found but require patience and diligence. In the rosary, I remember that I am a part of history both sacred and familial, that girls like me are creators of meaning, that we matter, that the repetition of our story, women’s story, will never be in vain, and that our pleading, yearning, and seeking are consecrated by God. Build love, accept our Heavenly Parents’ refining hands, remember women’s vital role in faith, family, and church: these are the lessons lovingly imparted through Grandma’s rites of root beer, sea glass, and rosary. You are loved. You are redeemable. You are essential.

It occurs to me now, as a woman in my fifties, that Grandma Jean’s Catholicism anchored me to my Mormonism in a way that I’m not sure has been afforded to my three daughters. They were gifted a beautiful inheritance of love and faith and a firm understanding of the embrace of Heavenly Parents whose arms are open wide to receive and refine them, but was women’s importance well and visually illustrated for them? Were they able to consistently observe the truth of loving words that affirm their integral roles in God’s church? Just like me, my daughters sang “I Am a Child of God” with fervor from molded plastic Primary chairs, but unlike me, they were not offered visual confirmation of their divine inheritance from the pews of Saint Pat’s. The root beer and sea glass of their childhood rites were abundant, but did I forget to offer them a rosary?

The certainty of women’s place in the Christian story is woven into the tapestries, carved into the altars, and painted on the walls of the faith of my foremothers. With every turn of head, my young eyes took in Mary as central and sacred and female saints as courageous symbols of discipleship; the feminine divine, not merely alluded to but actually present in every apse, nave, and transept. Our own Latter-day Saint chapels are dedicated to simpler beauty, perhaps designed to give room to thought and feeling guided by the inspiration of spirit versus the inspiration of art and story. The awe of our chapels must come from the gentle voice of the spirit that speaks of the truthfulness of expansive Latter-day Saint doctrine, that testifies of cocreation, equal partnership, and the crucial contribution women make to faith, family, and church.

But where is the breathtaking truth of that doctrine visually proved for my daughters? When asked a question about the lack of Christian symbolism found in our temples, President Gordon B. Hinckley said, “The lives of our people must become the most meaningful expression of our faith and, in fact, therefore, the symbol of our worship.” It’s a jaw-dropping proclamation and an awesome responsibility—we, modern Saints, are the symbol of our religion to each other and to the world. But who were the people offered as symbols of faith to my young girls as they guzzled root beer and gathered sea glass at my side? Were they all male? Where did they see themselves reflected back in the Church they love? Did I offer any substantive rite to help them remember their essential role? I could not give them the rosary of my grandmother, for it never really belonged to me.

Of course, in our Latter-day Saint tradition, much of the symbolism and ritual that women actively and visibly participate in is reserved for the sacred spaces of temple worship and not our weekly Sunday communion with each other and with Heavenly Parents. In the consecrated and set-apart spaces of our temples, women and men stand together side by side at the altar, echoing the sacred partnership of Adam and Eve, proclaiming the truth of Heavenly Parents and the divine lineage of all of God’s children. Although my daughters have not yet entered into that sacred space of endowed power, I still hope they understand the undeniable truth of the indispensable role women play in God's plan and in the living gospel of Jesus Christ.

But if I’m honest with myself, it was institutions outside of the Church that proclaimed the equality of their gender and centered women in their story. Perhaps, in the world they grew up in, my grandmother’s rosary was replaced by podiums, lecterns, and boardroom tables? Have they learned only a worldly view of gender equality? But where does that leave them in their spiritual home? Have I created enough space for them to sit comfortably next to me in the pews?

My daughters know so much more than I did at their ages. Their belief that “all are alike unto God” is unmovable and unshakable, and their understanding of grace and forgiveness likely surpasses my own. Their assumption of the ritual of root beer and sea glass, performed in hallowed halls of home and church, has offered them insight into the divine love of Heavenly Parents and the atoning love of Christ in ways unforeseen and almost foreign to me. And yet, I find myself pondering, was it enough for them to witness the work of mother and father at home, to see my husband and me laboring side by side as equals? I believe that domestic imagery matters, but I am unsure if it translates to their experience at church. They are loved. They are redeemable. Do they know they are essential at church and that their discipleship is vital?

I am left wondering if the bright truth of equality beamed at my girls from their vantage point within our chapel walls. Were my husband and I as equally yoked in our meaning-making at church as we were in our labor? Was I, am I, a visual and recognizable symbol of our people? Do women fully participate in the latter-day story we offer to the world? Is there equal partnership and co-creation in the Church—not just in the heavens or in the home? Do my daughters feel they can wholly bring their gifts, unique perspectives, wisdom, spiritual authority, and differences to the body of Christ?

The family rituals of root beer and sea glass were never meant to stand in place of the rituals of our church community; nor can a worldly affirmation of gender equality adequately express the spiritual importance of women. I wonder if my daughters feel that their own yearning to see themselves in the sacred, to understand themselves in full relationship with the divine, to perceive themselves as integral and necessary to the building of Zion has been validated. It’s hard to imagine that podiums, lecterns, and boardroom tables could provide my daughters with the same sense of their vital role in the Church as the imagery of Mother Mary and sister saints I saw, as Grandma wrapped her pale blue rosary beads around her prayerful hands. These seem like hollow replacements. I worry I have not done justice to Grandma Jean’s mystical rites.

Nevertheless, in Christ’s living church in the midst of glorious restoration there is always hope to be found. I do not despair. As my mind and spirit call me to an examination of questions about my participation in the gospel as a woman, as I wonder and wander through possibilities, solutions, pain, and hope, the transcendent rites of Grandma Jean continue to offer me wisdom. The remembered clinking of those long-ago rosary beads sounds in me as an invitation to remember my own role in God’s church; the cool taste of root beer on my tongue warms a desire to extend love and build bridges; and sun-warmed sea glass reminds me that the beauty of restoration is often found in the slow smoothing of sharp edges. Just as sea glass undergoes a transformation through time and friction, I am reminded that the journey toward full recognition of women's roles in the Church is ongoing. We are part of a living, evolving faith—a faith that, like the pieces of glass we collected, is shaped by the hands of God, sometimes gently, sometimes with more force, but always with the aim of making something whole and beautiful.

God has asked us, the men and women we call brothers and sisters, to be the symbols of our faith, the living embodiments of what it means to be a disciple of Christ. And in that work we can find joy, knowing that each step forward brings us closer to a whole and beautiful Zion where all are truly alike unto God, where we are of one heart and one mind, where women stand shoulder to shoulder with men in building the kingdom of our Heavenly Mother and Heavenly Father. My daughters have not been gifted Grandma Jean's rosary, but they have inherited something just as sacred: the call to participate fully in the ongoing restoration of the gospel, to see themselves as cocreators in the work of building Zion.

You are loved. You are redeemable. You have work to do. This is the legacy I can offer them. I hope it is enough.

Amy Watkins Jensen is a humanities teacher in Oakland, CA. You can find her on Instagram @womenonthestand in respectful dialogue about women in the Church.

Art by Sarah Hawkes.

Perhaps one place they can sense the spiritual importance of women is indeed in the lives of women around them - Primary, Sunday school, and YW leaders; in service received and offered through Relief Society and ministering, and even organists and music leaders who are often (though not exclusively) female. While we don't have Saints the same way Catholics do, the stories of scriptural women and pioneer women (see the Saints series of books) also serve as powerful symbols and examples.

Beautiful Amy, my mother is a convert to the church from her childhood in Catholicism. I recently visited a church where her ancestor helped to create the stain glass, there really is something in the faith of our Mothers, a continued thread.