This Is Grace

I know little of the fatigue experienced by a nurse, or a waiter, a day-laborer, a migrant, or the poor—all unique types of fatigue known best by those who experience them. But I know intimately the fatigue of a single parent, the exhaustion that comes from parenting three obstreperous boys alone.

Many days, I rise before the kids to go to the gym, and so they are already stirring by the time I come home. Then, I race to get breakfast on the table and binders into backpacks. It’s a mad dash as I help my boys take medicine and make sure the lunches have the right combination of each boy’s preferences, hoping against hope that today might be the day they actually eat instead of playing all through lunch. Then, I drop one off at middle school and the others off at elementary school and sprint on my bike off to the cancer center where I work. Each hour is almost always scheduled, often down to the very minute, until, at exactly 1:58—I’ve timed it to make sure I account for every contingency but nothing more—I hop back on my bike and race to school to grab the boys again, and then spend the day, as many stay-at-home parents do, whisking boys to lessons and practices, attempting to ensure practicing, reading, and homework are done, tending to scuffed knees and bruised egos, breaking up fights, monitoring friends, making dinner, attempting to ensure they eat, battling the allure of screens, helping them get on pajamas, overseeing brushing of teeth, and then settling in for bedtime, reading from whatever is the novel du jour, helping with prayers and bedtime songs, and then finally praying inwardly that they will, for the love of everything or anything, please fall asleep.

None of this is to complain. My life is richly blessed—most especially by the presence of these three boys. My material needs are consistently met and I do not wish to complain or make out that my situation is harder than anyone else’s—but that doesn’t mean it isn’t hard.

Often, by the time I come to that vanquishing moment at the end of the day when the boys are finally horizontal and I can at last lay my own body down on the floor next to the bunk of the two younger ones, I am both entirely drained but also longing for some space for my brain—for a moment during which I will not be pressed in upon by the insistent, incessant, never-ending needs of children. By that time, I am desperately grateful to not be parsing every moment, every second—and I find myself longing to take a moment to read.

I’m religious about staying off my phone when the kids are awake, and so it is often in that moment while I lie on the floor that I will pull out my phone and open the Wall Street Journal or New York Times. And that is what happened one day last week after the boys were finally in bed: I lay on the floor, exhausted, with my eight-year-old’s hand held in my right hand as he fell asleep and my iPhone in my left hand as I read. Somehow, though, at that moment, I suddenly knew my phone was not meant to be on. So, I laid it down on my chest and, as I did, I found my attention riveted on my son’s small hand held in mine. To my mind in that instant came very distinctly the thought:

This is grace.

And suddenly it was as if a veil was torn from before my eyes, and, for the first time, I became alive to the reality around me: the windows, just ajar, through which came the slightest rustle of a breeze and the roaring of a passing plane; the way the dim light from the hallway cast a shadow across the ceiling from the single light fixture there; the curved slant of the chair against the stark line of the desk; the whistle of the air filter in the corner; the cushion of the rug beneath my back; the spring of the pillow under my head; and the slight tremble on the ground as a car passed in front of our home.

But beyond being acutely aware of these sensory details, my attention was riveted on my hand—or, rather, on our hands together. It was, for just a moment, as if my hand became also my ear and my eye. Not only could I feel the curl of my son’s fingers as he clasped my own, but it was as if through my hand I was hearing the huuuuaaa (inspiration) and whoooooooo (expiration) of his deepening breathing as he transitioned into sleep and was seeing the rise and fall of his chest as that same breathing slowed. I could hear the rustle of the sheets each time he stirred on his way to sleep and see the imperceptible and gradual slackening of his muscles as his body surrendered itself to slumber. And, against the tips of my fingers, I could feel the gentle insistence of his radial pulse as blood rushed into and receded away from his fingers: life flowing and ebbing and rushing in again as each second passed.

As these subtleties pressed upon my mind, I was led to what I can only describe as a most sacred ecstatic insight: This—these two hands atop one another, these fingers interlaced, this slowing breath and this moment shimmering with silent spiritual splendor—is all there is. In other words: The beauty, fullness, and meaning that will constitute heaven filled that moment. Heaven—or at least so it seemed—consists in a personal epiphany that allows us to see, to hear, and to fully embrace the beauty behind the scrim veiling these earthly eyes. Becoming like God may be a way of being and seeing, a spilling over and out of divine abundance such that the effluence courses through otherwise mundane reality and enlivens it with the thrum of God.

This news came also with this realization: Heaven is like manna—it can only be savored on its chosen day because this portion of manna will never exist again. My youngest son will never be eight years, three months, and twenty-one days old again. Soon, he will pass through that imperceptible portal where it is no longer a thing to hold dad’s hand while he drifts to sleep, and, once that has happened, this tableau will be lost for all eternity—to be replaced, forever in an ongoing evolution, with whatever tomorrow’s manna will be, by whatever new tableau I will then need to learn to slow down to savor.

In the end, this moment—this leaping forth of beauty—did not solve anything nor even directly bring salve for any wounds. For reasons too personal to share here, the last years have often left me groaning and splintering, like a beam bearing far too much weight. I have spent months that have stretched into years journeying through my own version of what Jeffrey R. Holland once called “the battered landscape of . . . despair.” And this moment of seeing and feeling and sensing grace did not answer any of my persistent questions, nor did it heal any of the wounds I’ve now been nursing for so long.

But while I found no balm for my pain, I was also reminded in that moment that we do not believe in a perfect Eden lost, but in a mournful yet meaningful mortality gained. Grace cannot be the absence of sorrow because even God weeps. Grace cannot be the end of suffering because Jesus carried his cross. Grace cannot be bliss because being bound in love will leave us forever alive to each other’s suffering.

And that is the truth about grace: even its endowment does not restore what time will take away. Indeed, suffering cannot fully be grace’s opposite; instead, the two weave themselves through one another. Grace is because suffering is. As Adam Miller has argued, the world is always ending, and it is likewise always beginning—and even grace cannot change that eternal churn. In fact, in some measure, I wonder if grace is the churn. Beauty shimmers in part because its incarnation in this moment must always fade away. Indeed, it is probable that my soul could only have opened to this insight in this way, at this moment, precisely because it has been cracked open by the very suffering that has broken me asunder. To be clear, my most foundational theological belief is this: God will never cause or condone suffering. Yet, since we exist as eternal beings in an oppositional universe, this is my secondary and nearly as resolute conviction: Our Heavenly Parents can consecrate suffering they do not cause or condone. Thus, while we are never meant needlessly to remain party to suffering, yet we can always trust that God will raise a phoenix, even from our darkest ashes. That light will make its way into and finally illuminate even what may initially seem to be the loneliest, scariest, and seemingly most impenetrable darkness.

God is light; and light finds a way.

In the meantime, we are not meant to construct a world where suffering ceases so much as we are meant to transform suffering forever into love.

Of course, as it always does, life did not put itself on pause to allow me to savor that insight for long. Like clouds that had parted to allow a glimpse of a resplendent sky, and then closed just as quickly, soon the timer rang on the oven, the washing machine finished its cycle, and it was time to take up my laptop and wade back into the morass.

Apparently grace doesn’t prevent email backlog either.

But still, even the jarring intrusion of these realities could not fully break the spell. Slowly, I opened my fingers one by one. Carefully, I disentangled our clasped hands. Silently, I eased myself off the floor to return to my to-dos. But even as I did so, I knew I had been transformed. Somehow, lying on that floor, listening to those breaths, feeling that pulse, sensing that grace, I had been gifted the type of insight that seeps into knowing and seeing. Grace abounds because we who receive it learn to see with new eyes. Grace overwhelms us with beauty amidst impermanence—in the welter of the churn—not because it eradicates sorrow, but because it changes who we are and how we see.

Tyler Johnson is a medical oncologist and associate editor at Wayfare. To subscribe to Tyler’s column, first subscribe to Wayfare, then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for On the Road to Jericho.

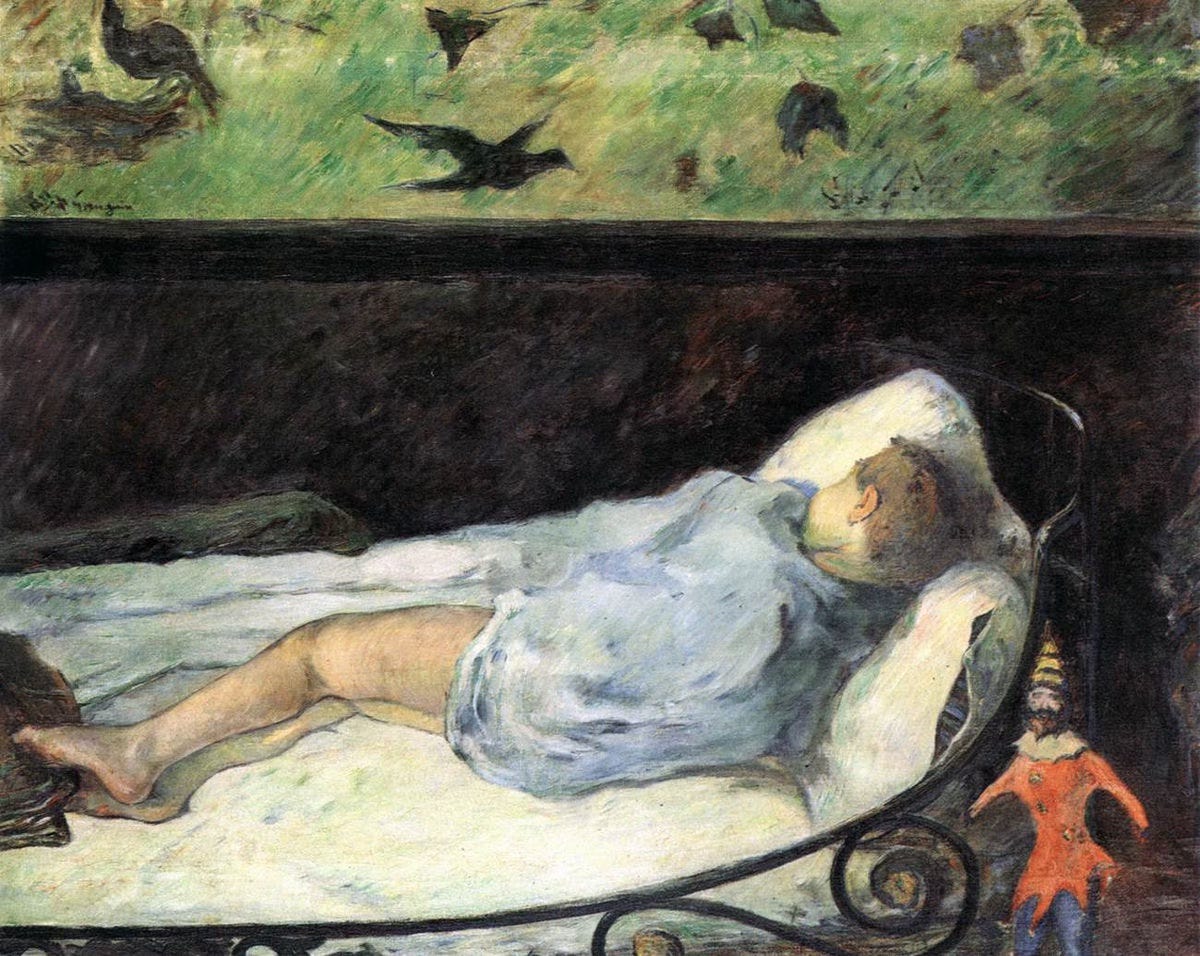

Art by Paul Gauguin (1848–1903).

Beautiful writing. I love "God is light, and light finds a way..." I also loved the thought that we are "meant to transform suffering forever into love." That is what we do... in our families, our homes, our commmunities. Thanks. :)

I have read and reread this gift you have offered up, and I have savored every beautiful word and thought. Thank you from the very depths of my heavy soul.