“There is a season, and a time,” writes the author of Ecclesiastes, “to every purpose under heaven: a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted; a time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up; a time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; a time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing; a time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away; a time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak; a time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace” (Eccl. 3:1–8, KJV).

The premise of this well-known passage from Ecclesiastes is that our actions might be sensibly ordered—that there is a narrative logic to our passage through time. Birth precedes death; planting precedes reaping; and rending precedes sewing. But we live in a world increasingly divorced from narrative, linear models of time; it is now possible to harvest food without ever planting a seed and to wear holes in clothes repeatedly, without ever patching those holes or sewing a new garment. For each of us, as for Hamlet, “time is out of joint.” Alienated from the orderly world of Ecclesiastes, we experience a world stripped of narrative continuity as the social structures and strictures that give meaning to time’s passage cede ground to a globalized, on-demand economy. We eat strawberries in winter; we answer work emails in bed, after 10 p.m.; and we shop Amazon deals in Sunday School. In the absence of meaningful temporal boundaries, we slip from moment to moment without a clear sense of how or when we lost the plot of our own lives.

This crisis of temporality is the subject of both Eugene Vodolazkin’s brilliant novel Laurus and Byung-Chul Han’s moving manifesto The Scent of Time. Both books reflect on the atomization of time: our postmodern struggle to discern an orderly pattern in the sequence of moments, days, and seasons that we observe and experience. Although we might regard this discontinuity as a matter of social boundaries, Han insists that “the temporal crisis is experienced as an identity crisis” (TST 43). Our struggle for duration, for a period of time indivisible by the distractions of twenty-first century life, is really the struggle to establish and maintain a coherent sense of self.

Vodolazkin foregrounds the temptation of living a fragmented life in the opening lines of his novel. He writes of his titular character,

He had four names at various times. A person’s life is heterogeneous, so this could be seen as an advantage. Life’s parts sometimes have little in common, so little that it might appear various people lived them. When this happens, it is difficult not to feel surprised that all these people carry the same name” (L 3).

The eponymous hero of Laurus is by turns a hermit, a holy man, a doctor, and a pilgrim, wending his way through fifteenth century Russia to Jerusalem and back. Known as Arseny and Ustin and Amvrosy and Laurus at various points in the novel, Vodolazkin’s protagonist mourns the death of multiple family members in his youth and spends the rest of his life torn between past and future, seeking desperately to recall lost joys or to anticipate a postmortal reunion. As a result, Vodolazkin explains, “he himself did not always understand what time ought to be considered as the present” (L 5). Only his body, and its persistent needs, keep Arseny anchored to the rhythms and sequences of daily life.

Because his body distracts him from past and future joys, Arseny spends his life struggling against physiological appetites and imperatives. He resists desire, because “if you give your flesh a finger, it will grab an entire hand,” and embraces suffering, seeking to confirm his commitment to past and future by ignoring present pains of cold and hunger and injury (L 164). Vodolazkin memorializes this masochistic urge in brilliant prose reminiscent of Dostoyevsky’s finest passages, celebrating his hero’s nocturnal trysts with mosquitos in language that recalls both the bloodied Christ in Gethsemane and one of the Bible’s archetypal sinners, who “came out red” (Genesis 25:25). Vodolazkin writes,

On damp, warm nights, when the air turned into a humming blob, he stripped naked and stepped onto the gravestone in front of his house. He experienced an unusual sensation when he ran his hand along his body. It felt as if his skin was covered with thick fur, like Esau’s. The growth turned to blood when he touched it. Arseny did not see the blood in the dark but he sensed its scent and heard the crunch of crushed insects. Mostly, though, he paid them no mind, since he diligently prayed [for an expiation of past sins]. (L 151)

This bloodletting releases Arseny from consciousness and from the present, but he wakes each morning, naked and bloodied on the ground, to find himself confronted, again, by the return of bodily urges from which he seeks an escape into the past and the future.

In fixing his gaze on distant temporal horizons, Arseny seeks an escape from the story of his life, a narrative now that strings together moments into a coherent whole. But Han insists—and Arseny discovers—that any rejection of the present and of storytelling renders the past and future inaccessible. “The end of narration,” Han argues, “is in the first place a temporal crisis. It destroys that temporal gravitation which gathers the past and future into the present” (TST 49). Arseny tries to ignore the scent of his own blood and to forget the story of his own embodied present because “narration gives time a scent” (TST 18). “A scent is slow,” Han explains, so “it is not adapted to the age of haste. Scents cannot be presented in as fast a sequence as optical images. In contrast to the latter, they can also not be accelerated” (TST 46). A scent, in other words, preserves our sense of duration and story, inviting us to linger in a present linked to both past and future. The acceleration that Arseny seeks—hoping he will wake up from a midnight bloodletting to discover himself at the end of the world, where past and future collide, without enduring the interminable present—can only be achieved by foreswearing narrative and the orderly progression from one moment to another.

Vodolazkin tempts the reader to join Arseny, in anticipation of the apocalypse and an escape from time. One of Arseny’s companions, on the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, prophesies “the end of the world in 1492,” teasing the reader with hints that Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Western Hemisphere signals the end of sacred time (L 186). But if the world ends, its surcease passes unnoticed by Arseny, who lives through that year and marks its end only by becoming a monk and taking a new name: Laurus. The world ends only in the sense that Laurus ceases to participate in its inexorable story and begins to experience creation as a series of recurrences: “Laurus lost track of forward-moving time. Laurus now sensed only cyclical time, which was a closed loop: the time of a day, of a week, or of a year. . . . Among temporal indicators, the words one day came to mind ever more frequently. Laurus liked those words because they overcame the curse of time. They also confirmed the singularity and lack of repeatability of everything that had occurred” (L 339). Divorced from story and from time’s linear flow, Laurus finally feels himself at peace, able to bask in the present without constantly anticipating the future or lamenting the past. In presentism, he finds peace.

Han lauds this monastic escape into a life of contemplation as a solution to twenty-first-century processes of “accelerated production and destruction” (TST 113). But Laurus discovers, and Vodolazkin insists, that the vita contemplativa is an insufficient answer. The purpose of contemplation, Han suggests, is to ensure the intentionality of action because “without the determination to act, the human being atrophies into a homo laborans,” a drudge whose presentism is either endured at the behest of others or perpetuated without purpose, mired in an interminable now. Action is a disruption of this status quo, an insistence that time begin anew. Quoting Hannah Arendt, Han allows that “the miracle that saves the world . . . is ultimately the fact of natality” (TST 102). Only as the vita contemplativa gives way to a new birth and a new world and a new story, linking past, present, and future, is contemplation made meaningful.

Laurus concludes much as it began, with a dramatic scene of birth that shocks Laurus out of a comfortable stasis. With this natal surprise, Vodolazkin insists upon both the cyclicality and the linearity of time, as the recurrence of former events provides the monk’s past, present, and future with new meaning; only a return to the novel’s earliest events allows Arseny-cum-Laurus to move forward, towards death, with confidence that his passage through time has been meaningful.

The individuals who witness his death agree that they cannot comprehend the meaning of that event; they

. . . have not understood a thing about it. And do you yourselves understand it? asks Zygfryd.

Do we? The blacksmith mulls that over and looks at Zygfryd. Of course we, too, do not understand. (L 362)

The import of his life and death is comprehensible only to those who have seen the end from the beginning, who have seen time embedded in narrative, so that the circularity of Vodolazkin’s novel is not a mystery but a revelation.

I read that passage—the final words of Laurus—while sitting in a boxy play center, as my seven-year-old caromed from slide to cargo net to birthday cake in a frenzy of adrenaline, singing his congratulations to a classmate at the top of his lungs. With a strobe light pulsing and the latest pop hit blaring over the loudspeaker, I reread those words and wept because I had witnessed the triumphant reconciliation of past, present, and future in Vodolazkin’s novel. I understood.

Han complains that “the real problem today is the fact that life has lost the possibility of reaching a meaningful conclusion,” but Laurus attests to the inevitability of meaningful conclusions, even in the face of chaos and uncertainty and pain and doubt and birthday parties (TST 10). Although we cannot, from our atomistic present, understand the mystery whereby every past injustice will be transformed into a glorious future, Vodolazkin presents a model of time’s redemption in his novel. “In this surmounting of time,” he shows the reader “confirmation of the nonrandomness of everything that took place on the earth,” and that vision is deeply, deeply moving (L 186).

A birthday party is a time for laughing, not weeping. But as I closed the pages of Laurus and wiped the tears from my eyes, I smiled awkwardly at the gaggle of parents glancing in my direction, nodded in time to the music, and gave thanks that time was out of joint.

Zachary McLeod Hutchins is the author of several books for Latter-day Saint readers, including Joseph: An Epic and The Best Gifts: Seeking Earnestly for Spiritual Power.

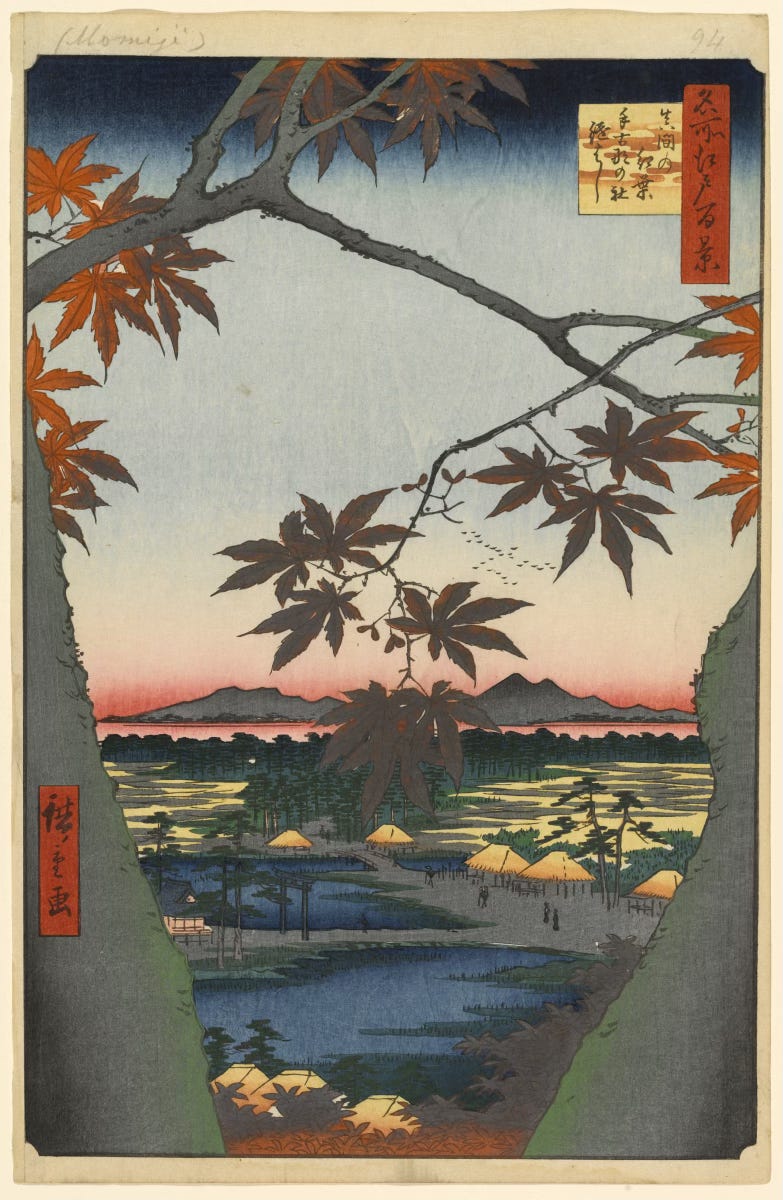

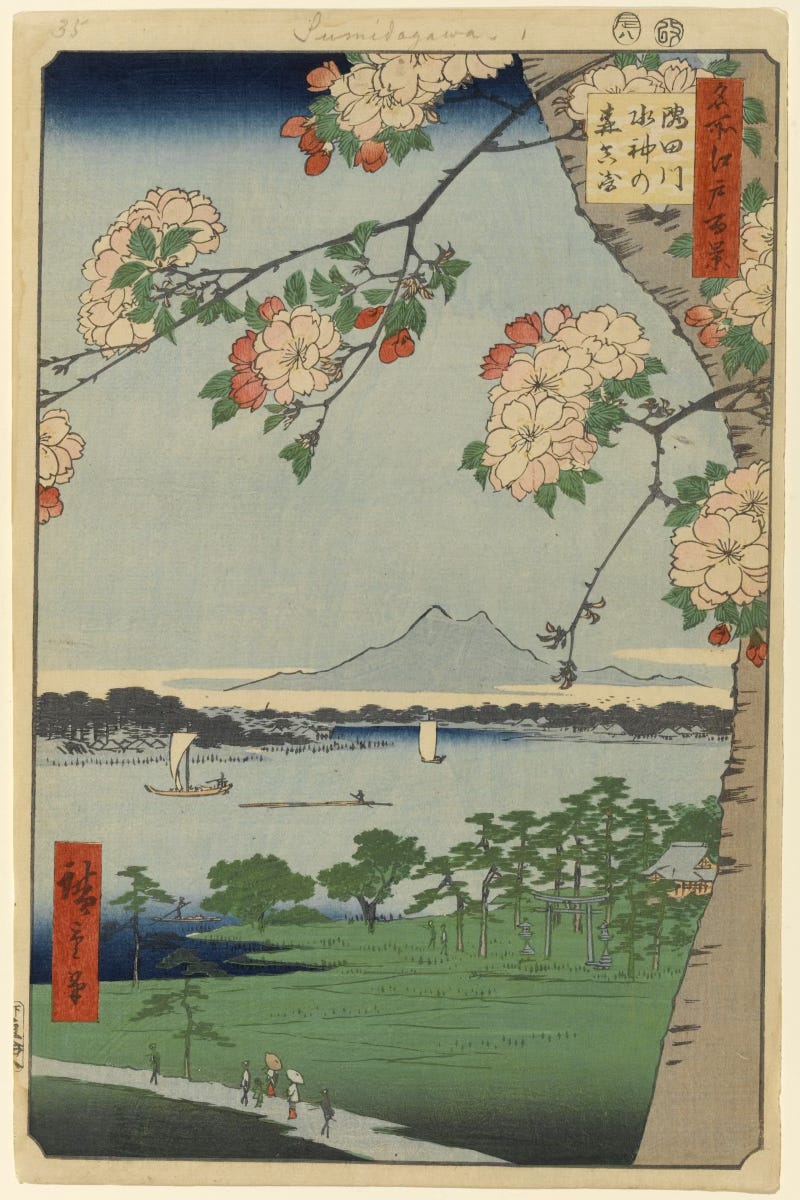

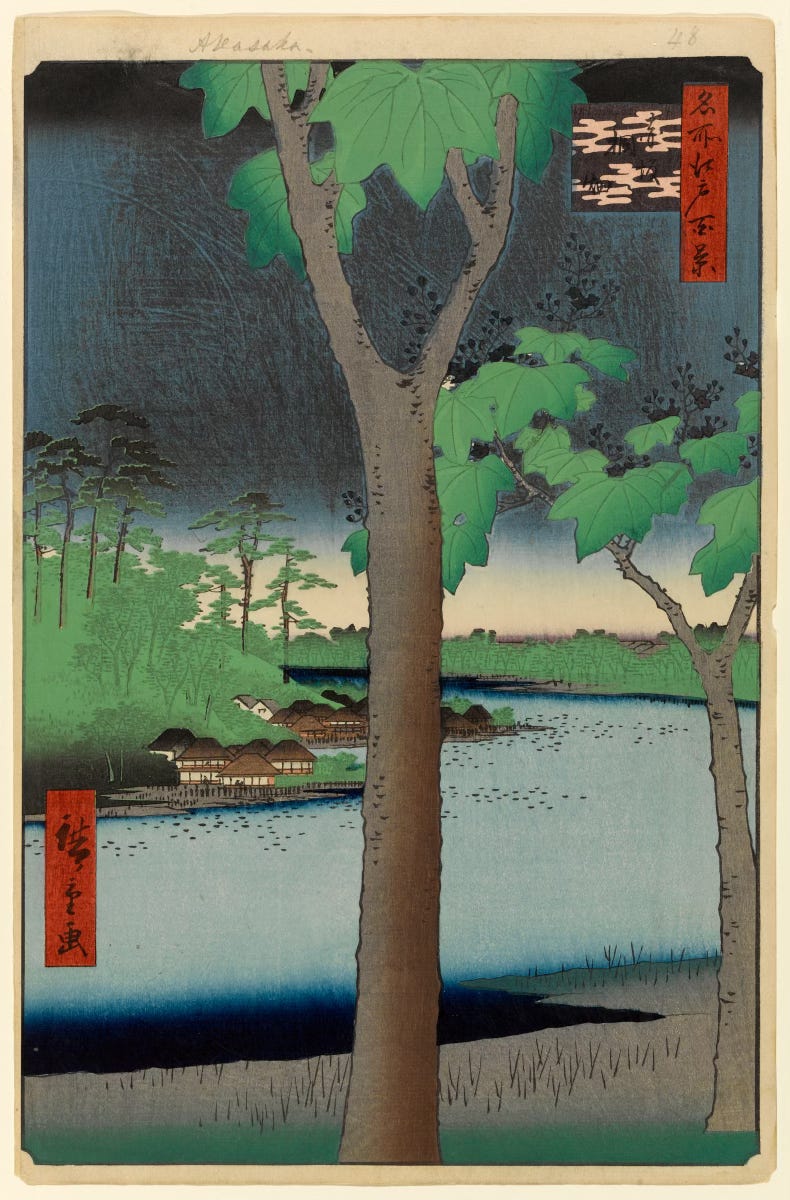

Art from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856–1859) by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858).