“We are endlessly oned to Him in love” – Julian of Norwich1

We tend to refer to the atonement as a power in itself, a transcendent force or event which can cleanse, elevate, or heal us. Contrary to this common perception, President Nelson makes a disconcerting disavowal: “there is no amorphous entity called ‘the Atonement’ upon which we may call for succor, healing, forgiveness, or power. Jesus Christ is the source…. The Savior’s atoning sacrifice. . . is best understood when we expressly and clearly connect it to Him.”2

This clarification is enormously important for a few reasons. First, because we (myself included) are easily absorbed in constructing “theologies of atonement,” theories that attempt to explain the exact mechanics by which mercy and justice are reconciled, or whether ransom or substitution are better analogies for what transpired, or how the work of atoning was divided between Gethsemane and Golgotha, and so forth. Second, because turning the atonement into a concrete thing or episode places it in the past and invokes historical memory more than a living presence, an ongoing encounter. And finally, because the prominence of the word “atonement,” and its theological weight and ambiguity, may obscure the greater reality it was originally intended to describe: the transformative, healing love of Jesus Christ.

This obfuscation has happened in our own Restoration history, and continues to occur when we misquote and thereby mischaracterize Joseph Smith’s words on the subject. “All things which pertain to our religion are only appendages to the atonement,” is the phrase we frequently read and hear in talks and publications. But Joseph never uttered those words. What Joseph actually said was, “The fundamental principles of our religion [are] the testimony of the apostles and prophets concerning Jesus Christ, ‘that he died, was buried, and rose again the third day, and ascended up into heaven;’ and all other things are only appendages to these.”3

So Joseph was not referring to the atonement, nor was he turning the concrete love of Christ into an “amorphous entity.” He was rather pointing us to something more expansive and at the same time much more concrete than a theological concept. That Jesus suffered a terrible death out of boundless love for and solidarity with us. That he rose again—affirming his divinity to a cloud of witnesses and heralding the unconditional gift of new life that each one of us will know. And that he then went to heaven, as he said, to “prepare a place” for us.

That language is simple and immediate—unclouded by abstractions. Similarly, if we look to the Doctrine and Covenants, we do not find doctrinal expositions of atonement. (We only find the word once in 29:1: “I…atoned for your sins.”) What we do find is confirmation of his life and suffering death as witnesses of his love. The most protracted description comes in section 19:

For behold, I, God, have suffered these things for all, that they might not suffer if they would repent; But if they would not repent they must suffer even as I; Which suffering caused myself, even God, the greatest of all, to tremble because of pain, and to bleed at every pore, and to suffer both body and spirit—and would that I might not drink the bitter cup, and shrink (16-18).

What he suffered, he suffered “for” us. Whether that suffering was in our place, in solidarity with us, through an act of divine empathy, by exposure to Satan’s fury or to the Spirit’s absence or to the pains of vicariously felt guilt, we cannot know. And even if we did, the mechanics of atonement would only distract us from the motive—he loved us.

Time’s arrow only moves forward. Choices we have made are in the past, but consequences echo through the ages before us. The irreversibility of the past has been felt painfully by everyone who wishes they could retract a caustic word, an impulsive act, or a rushed yellow light that did not end well. The arrow of time can seem to make us prisoners of our own agency—since the past cannot be changed. Except it can.

I offer a few thoughts that suggest in more concrete terms what may be behind the word “atonement.” When I act in ways that harm others, I am generally being unloving to myself as well as to others. As a parent never withdraws her love for a child, neither does the Lord turn away in hurt or anger. We insulate ourselves from the Spirit’s influence. The Spirit pervades all the cosmos, and “fills the immensity of space.” God sends his rain on the just and the unjust. He leaves the 99 to rescue the 1, he rejoices in the prodigal, and pays the late laborers as much as the first. The asymmetry of divine love annihilates all our preconceptions about justice and reciprocity.

God stands evermore at the door and knocks, even to “battering our heart,” in John Donne’s words.4 Yet until our heart softens, we can never expose that stony heart to that which “gives life to all things.” Spiritual death is self-imposed. In light of this litany emphasizing ourselves rather than God as the source of alienation and pain, the hardening of our own hearts—through self-loathing, disappointment, shame or guilt or stubbornness—the word repent carries new valence. It is not about “doing penance,” as the term was translated in the Latin Bible that had the monopoly on Christian understanding for 1500 years. The point is, “change your heart,” “melt those walls of iron,” “open the doors to forgiveness,” “let my love in.”

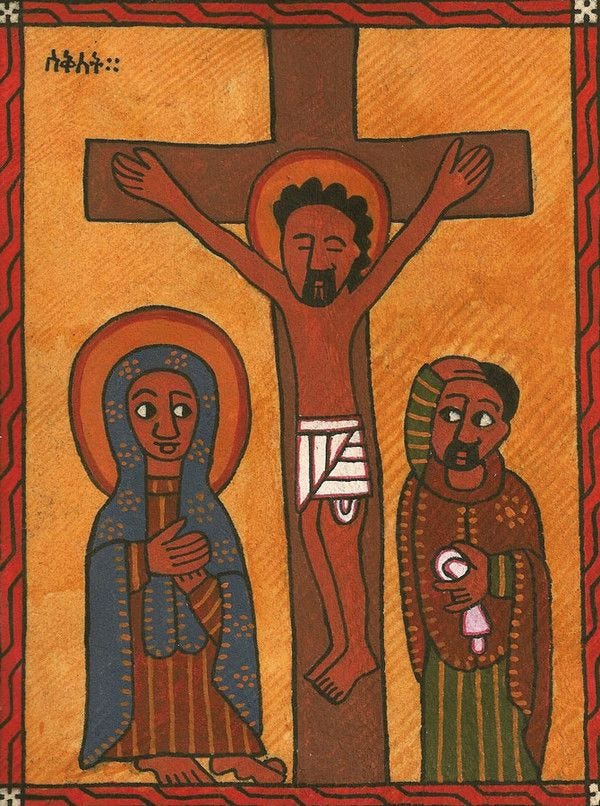

Almost a thousand years ago, the French philosopher and mystic Peter Abelard suggested that Christ’s suffering was efficacious because it provided a shock of love to disarm us.5 Seeing—or learning—that our very God would endure such agony and death just might at last break through the armor of self-reproach and convince us that we are worth loving after all.

The phrasing that points to his suffering for our sins may suggest two possibilities. 1) The entire passion of Christ was motivated by and directed toward a healing from those sins. And 2) in an act of supreme empathy, Christ did literally suffer those consequences of spiritual pain and desolation that we in our darkest moments do and may yet experience. Henri Nouwen writes, when “we try to enter into a dislocated world,” our connection will not “be perceived as authentic unless it comes from a heart wounded by the suffering about which we speak.”6 That is as true of gods as it is of disciples.

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

Joseph Smith said (speaking of baptism for the dead) that as soon as their friends on earth lived the law of the gospel the dead would be set free. When we work to correct the effect of their sins, to make restitution, we participate with Christ in the burden bearing that defines atonement. We, like Paul, make up in our bodies that which Christ left for us to do. (Colossians 1:24).

Wonderful article, Terryl ❤️