The Playground Linguist

Language, Subjectivity, and Universal Love

Every day I watch my three-year-old son learn to navigate the politics of the playground in languages not his own.

We currently live in Bangkok, Thailand, where my husband works as a United States Foreign Service Officer. The city is vibrant and varied. Motorbikes zip in and out of traffic and neon-bright tuk-tuks ferry tourists to golden temples or bustling markets ripe with the smells of lime, coriander, and grilled pork. On any given day, I see Buddhist monks in saffron robes, Thai middle school students in lilac blue uniforms, Japanese businessmen clutching leather briefcases, and American babies carried by their Cambodian nannies.

While my husband conducts visa interviews or helps distressed American citizens, I’ve primarily learned the lay (and law) of the land through the city’s parks and playgrounds. Our apartment complex’s communal playground offers a lesson in cultural geography. Like Bangkok, the playground is multicultural and multilingual. Thai, Japanese, English, Russian, and Burmese (spoken in Myanmar) are the predominant languages I hear as children run around, bounce up and down on the see-saws, try to climb up the scuffed yellow slides, and scoot past each other on their balance bikes.

I usually observe this chaos while sitting on a tiled bench near the sandbox while my three-year-old son pours sand into a dump truck. As he plays—whether by himself or with others—I sometimes try to play the role of a bored observer, hoping to facilitate his sense of adventure and independence.

To paraphrase Hamlet, “the play’s the thing.” In this case, play is how children grow, how they make mistakes, how they draw limits, and how they explore their inner and social worlds. Play brings provocations, invitations, negotiations.

I like that idea. But I would like the idea more if I could guarantee that other children on the playground understood my son. Not knowing the language of the playground can be disorientating.

I watch as my son approaches a Japanese boy, clearly (in his mind) asking him for a turn with a toy car. The boy—who probably does not speak English, and would not understand toddlerese even if he does—ignores my son. What my son is trying to do is what I have asked him to do countless times—“ask to have a turn before taking a toy”—and I know that he is trying to make himself understood. I cannot rush to help; I do not know Japanese, and I cannot ask this boy to share. Instead, I feel pain for my son—trying so hard to be polite, yet ignored and misunderstood. I break my facade of a bored observer and interrupt his play. “Thanks for asking politely, buddy!” I call out.

Later, as we take the elevator back to our apartment, I tell my son that not every child on the playground will understand him. “That little boy is from Japan and speaks Japanese,” I say.

“It’s okay, Mom,” my son says, unfazed. “Next time, I sing ‘Totoro’ to him.”

At its very mention, the cheery theme song from My Neighbor Totoro fills my mind, and I laugh. I give my son’s hand an extra squeeze, contemplating the miracle of his working mind. He expects to be understood. To him, there is no doubt that singing a song from a Japanese cartoon will help others know he wants their friendship, even if he cannot pronounce Konnichiwa.

From child psychologists and self-described “experts” trying to sell the latest language-learning app, to moms I meet at the park, I’m constantly told that the best time for a child to learn “another” language is when they are young. There is truth to this. I’ve read the research, looked at data—neural pathways are malleable and impressionable during these crucial early years of life. And younger children learn differently than older children or adults; they generally communicate through imitation, through playful interactions, and are less embarrassed about making mistakes.

But children are learning their first language—their mother tongue—during their early years, too. Blending sibilants, omitting and adding verbs or pronouns, recognizing that mom and dad call one flying object a bird, and yet another flying object a plane, trying to make themselves understood through motions, cries, and articulated mamas or papas. Learning even one language requires energy to organize, articulate, and experiment. I am no expert in the field, but from observing my young children, I sense how frustrating (and exhilarating) it can all be.

Learning one language is hard enough, let alone two or more. I perceive that my three-year-old resists any efforts to teach him Thai, whether through our Thai housekeeper or my limited phrases. He also gets upset when my husband and I speak languages we have learned throughout our lives—whether Spanish, French, Russian, or German—to him. Can’t you tell that I’m trying to learn your language, Mom? his eyes seem to say.

That unspoken question arrests me. What is my language? Not just English, but the language of Mom, the language of me? His memories and languages are developing together—bud and leaf—reaching towards the light of consciousness, absorbing his environment. I am, in many ways, his mother tongue.

Such a realization astounds and confounds me. It is sublime, in the true romantic sense of the word—both beautiful and terrifying. I find it beautiful that he craves the familiarity in my voice that he has known intimately since the womb—he wants to understand as much as he wants to be understood. But I am too aware of my own failures of expression. The divide between what I can and cannot speak terrifies me.

I try too hard to follow some sort of script, forgetting that my son doesn’t want perfection, he just wants me. And so I stumble along, mumbling and bumbling as I go, trying and failing and trying again to simultaneously learn and teach the languages of God.

If we see through a glass, darkly, then our other senses must be muddled, too. The words I hear and say might sound like when, as a girl, I would giggle “hello” to my sisters underwater, air bubbling from my smiling mouth, before returning to the surface and laughing about how funny we sounded.

Our mediums are distorted. It’s part of the world we live in, the water we swim in. We are all talking underwater, our language distorted with the warp and weft of differing human experiences and expectations. Truly, it is a miracle that we communicate at all, through voice, hands, eye contact, expressing the beauty and terror of embodiment. Every connection is a chance for rebirth, infused with the grace and suffering of our mother tongue.

Every day, my son learns how to navigate this bewildering world and its varied interactions, and every day, I try and fail and try again to teach him the languages of benevolence, patience, and gratitude. One day, while driving to the neighborhood baby café (a delightful little space with tables for brunching parents to disinterestedly watch their children play amongst communal, Montessori-style wooden toys), I warn my son that he needs to play nicely with any other kids there or else we will not come back.

He processes the threat. “We not come back?”

“No,” I say firmly. “We will not come back if you hit or yell. You need to behave.”

The baby café buzzes with activity, with half a dozen children exploring the play kitchen, the big-knobbed puzzles, and the carpeted floor road. My son gravitates towards the plastic excavators. I let my one-year-old daughter toddle around, while I browse the menu.

But there is already a problem. Another little boy around my son’s age has hoarded the construction vehicles. My son tries negotiating.

“We share?” he asks, vigorously nodding his head and holding out his hand.

The boy shakes his head and clutches the excavator more tightly.

My son tries again. “I play, too?”

The boy shakes his head again, this time with an emphatic Russian Nyet!

My son looks over at me with tears in his eyes. I can tell how hard he is trying, and I can sense that his fear of my threats is preventing him from doing what he would more naturally do—wrestle with the kid for possession of the toy. He is trying to be kind, but he is misunderstood.

The familiar parental pangs rush over me. I make a mental note to myself that I shouldn’t use threats as often as I would like, then try to figure out a way to defuse the situation. I decide to intervene. I can speak the language of this Russian boy, and I can try to make my son’s intentions understood.

I get down to their level and ask the little boy in Russian if they can play with the vehicles together. He understands. But more surprisingly to me, he acquiesces. The two sandy-haired boys enjoy parallel play with the construction vehicles—at least for a little while.

My world shifts as I speak Russian. It brings up different parts of my own memories, experiences, and challenges with language. I feel like a different person as I speak another language.

But I also feel others in the room shift when I start speaking Russian to the little boy. His mother—and the other Russian women with her—notice that someone is speaking their mother tongue in accents not their own. I am no longer part of their mis-en-scene, another random, anxious mother wrangling two small children. I feel their wariness.

Perhaps they realize that I can understand not only their small talk, but their large talk—about new lives in Bangkok, Russian communities in Pattaya and Phuket, teaming with draft dodgers, about finances, about schools, about government and neighborhood complaints. Or perhaps the mother simply dislikes how I handled the situation.

Armed with their language, I am not welcome. I am an interloper, an eavesdropper who understands too much (or, perhaps, in their view, too little).

And yet. Even as I feel their curious eyes follow me back to my table (where I try to keep my one-year-old daughter from spilling strawberry smoothie on my shirt), the boys continue to play pleasantly together.

Back at our apartment complex’s playground, misunderstandings continue to abound. Our housekeeper often brings my children to the playground when I have errands to run. When I return, she hands my squirmy, smiling daughter to me, regaling me with “how smart” my daughter is and how all the nannies at the playground love holding her.

“But there are too many Myanmar nannies,” our housekeeper says. “I don’t like Myanmar. Why are there so many of them?”

She complains of how loudly the Myanmar nannies speak at the playground, how they are always on their phones, how they get more jobs than Thai nannies because they speak English more fluently, how there are so many people from Myanmar now in Bangkok.

“Well, there is a civil war happening there,” I say too casually, trying to appear informed but instead sounding self-righteous. She ignores me, and instead talks about the rising cost of living in Bangkok. The Thai and Burmese have an embattled history of distrust, and she has learned this language about Myanmar over not only her own lifetime but through generational stories. Her comments about the Myanmar nannies elucidate these conflicts more than most textbooks ever could. The politics of the playground are alive, full of tension and promise, shaping the languages of adults and children.

That we speak different languages, that we cannot understand each other, can seem like a curse. That is how I have often read the story of the Tower of Babel, of God so displeased by His children’s pride that he scatters their ambitions by discombobulating their language. Miscommunication is painful indeed, whether among nations, genders, or generations. But what if we were never meant to understand each other perfectly? In searching for mastery, have I forgotten that God can speak through the heart and to my heart, in spite of my lingual limitations?

I still reach for heaven, though in the vision of a different city. I remember learning about the city of Enoch (in many ways, I now realize, a foil to Babel’s metropolis) during a Family Home Evening when I was six or seven years old. The story enthralled me. I imagined what it would be like for an entire city to be taken up into heaven. I asked my mom about the possibility.

“How would we do that?” I asked. “Is it possible to be taken up into heaven like the City of Enoch?”

“I think it is,” my mom said.

“How?” I asked.

“You could start by being kinder to your sister.”

Her response deflated my enthusiasm. I knew she was right, but I didn’t want her to be.

I’m older now, though not necessarily wiser. The story of Enoch’s city still captivates me. I still long for a world where all children “shall be taught of the LORD; and great shall be the peace of thy children” (Isaiah 54:13). I imagine a world where all children—my children, the children on the playground, children playing and working on the streets of Bangkok, children in war zones, fatherless or motherless children—grow up without fear, grow up in peace. It is a paradisiacal vision that has inspired poetry and psalms for centuries.

But I also see the difficulties of achieving such a world. I see mammon everywhere. I see it in the neon green drug dispensaries and the sleek fashion design houses that populate our street in Bangkok; I witness the downtrodden, asking for alms in the shadows of mega-malls; I feel it in my own heart, that gnawing, never-satiated hunger for more, more, more. Becoming a people of “one heart, one mind, with no poor” among us runs against whatever current we swim in. Might makes right, greed is good, war is peace. These messages of conflict beat a thumping bass drum, distorting my perception. Under this percussion, I fear that meekness is weakness in this world, whether on an interpersonal or geopolitical scale. Like Enoch’s contemporaries, I throw up my hands and say, “Zion is fled” from this world (Moses 7:69).

But words and stories of Enoch’s city remain, portraying powerful possibilities of what can be. I do not know the municipal practicalities of Enoch’s city—who swept the streets, who carried out the garbage, who fed the masses, who managed traffic. But I do believe that a holy language undergirded their city, protected them, and charged their interactions with their brothers and sisters with a kind of divinity until they saw God in each other as, “lovely in limbs…not his own” Christ’s love appeared “through the features of men’s faces.”

This powerful language exists, not just in scripture stories or in church talks, but in the grittiness of an international city, or the rubber turf of a Bangkok playground. I once witnessed two Enochs-in-miniature. A neighbor’s nanny brought a bubble wand for the children to share. Every child got a turn, but my son did not want to give up the toy when the time came. There were tears and screams from all the children, pushing and pulling at the bubble wand and each other, until a curly-haired six-year-old and her equally curly-headed three-year-old sister parted the sea of squabbling boys, holding out gold medallions of Ritz crackers. Instantly, there was calm as the small boys munched on their crackers, crumbs spilling onto the tiled floor. I marveled, witnessing these girls’ gift of discernment through the babel of gimmes filling the air.

Without a word, they changed the contours of an afternoon.

I wish all conflict could be resolved like that, breaking bread together over a communal table. But our world is marked with deep wounds; we will never completely understand each other. I am comforted that God is a polyglot. I am comforted even more that the words and actions of Christ provide salve “for the healing of the nations” (Revelation 22:2). Christ is the One to speak to us in our own language, to show us a better way to live and how to love our enemies. Learning any language is an atonement—a way to bridge divides, learn humility, and allow grace to embrace us.

In learning the languages of God’s love, I am still a child. I experiment with new vocabulary, I synthesize syntax, and I practice proficiency in the everyday playground politics of my interactions with those around me. I am learning that speaking different languages (or different dialects) of the soul can bring connection rather than division. But it takes patience, grace, and the willingness to try and fail and try again.

Nowhere is this more true than in my relationships with my children. They aim to learn my language, but they also yearn for me to understand theirs. They offer openness. A sense of wonder illuminates their interactions. Every leaf needs examination, every flower is a heavenly gift, every twig is reimagined as a dinosaur talon. They bring the language of restoration with them, making old things new, speaking with the tongue of angels in ways I have forgotten.

Megan Armknecht is a writer and historian currently based out of Bangkok, where she lives with her husband and two children.

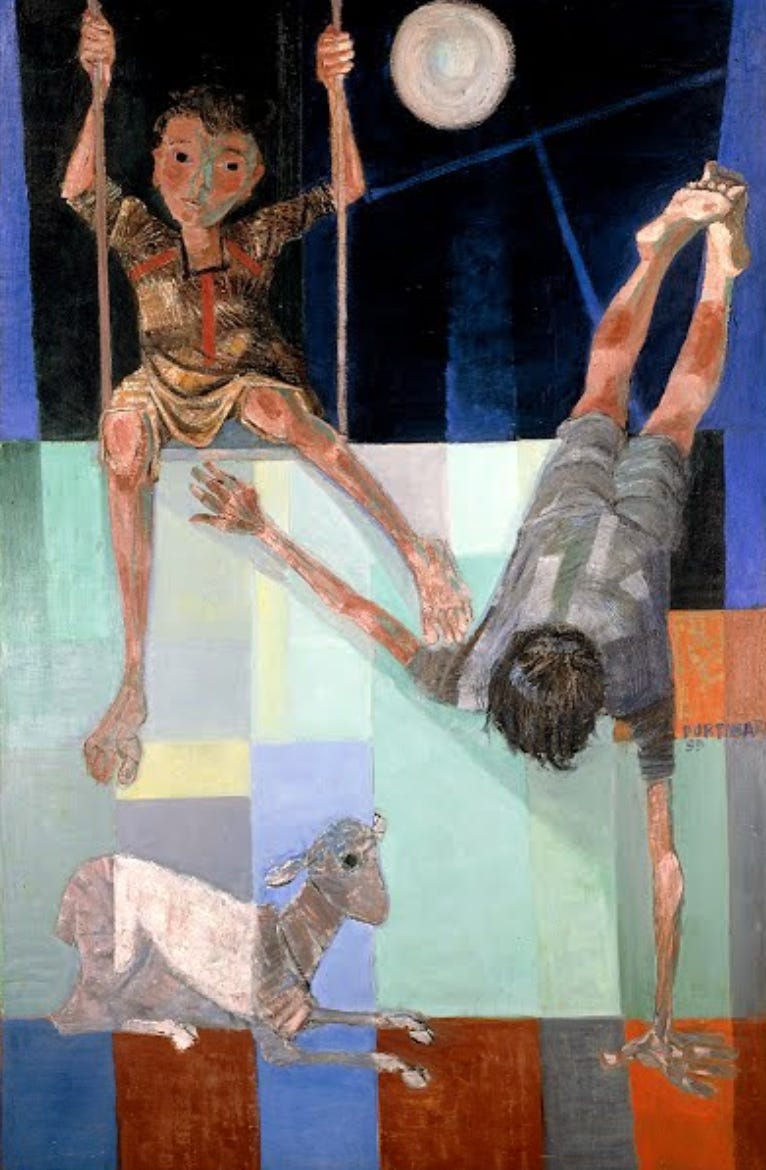

Art by Candido Portinari.

REMEMBERING FATHERS

Fathers, In Medias Res

In honor of Father’s Day we present a collection of essays that explores the sacredness and complexity of fatherhood. We invite you to read and consider them, allowing their stories and ideas to challenge and expand the way you view the fathers in your life.

WAYFARE ARTS AND CULTURE

Please enjoy these reviews and cultural perspectives and consider signing up for the Wayfare Arts and Culture section. Manage your subscription and turn on notifications for Arts and Culture.

Bodies and Churches

The wintering sun is low but not yet gone as I step into the old white steepled building full of Joel Church’s paintings. Light seeps clearly through the cold open room, spreading into corners, revealing dozens of darkly painted canvases bearing human forms. There are few people inside, making each voice distinct and each footstep noticeable—Belchertown…

"Lead Kindly Light"

One thing I remember hearing a lot in LDS church meetings as a kid was the promise, usually slipped into a sermon or testimony, that if parents stay true to the faith, our families, wayward children and all, would turn out OK. I’m sure at the time I rejected such pronouncements as so much wishful thinking, but in retrospect, I was probably too dismissiv…

Article 13 Episode 2: For Mankind

American boys and men are facing growing challenges in school, in the labor force, and in our culture. Richard Reeves, author of Of Boys and Men, documents those challenges and the steps it will take to solve them — which include a new cultural script for masculinity.

JOIN US

The Wayfare Festival 2025

Join Wayfare for our second annual summer festival. This year’s gathering features Adam Miller, Terryl Givens, Kathryn Knight Sonntag, Chad Ford, Esther Candari, James Goldberg and many more.

CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS

Invitation to Submit Original Hymns

Wayfare seeks original hymns to be considered for publication in its signature print issues, and for potential use in future projects. Andrew Maxfield, Wayfare’s Director of Music, invites you to offer your compositions for consideration.

Love this, Megan, and you! Thank you for sharing.

A reflection on God as a polyglot:

I had an extraordinary experience with the voice of God through the Spirit. I was driving too fast down a narrow street when I distinctly heard the voice of my driving instructor from years ago asking me what I should look out for between parked cars. I thought of children and slowed down. As I was doing so, a small boy ran out in front of the car; I slammed on the brakes; and when I stopped, the boy was standing in front of the vehicle with his hands on the hood.

My first thought was, wow, God chose the voice of my instructor to get the urgent message across! That’s astonishing!

My later thought was that it was perhaps my own mind that selected and generated the voice; that the Spirit communicates with me at a subconscious level, and my mind interpreted the message as it rose through layers of consciousness into a form customised to the immediate need.

Perhaps the language that God speaks lies deeper than articulated words and verbal thoughts.