The Disposition of Mormonism

A Peculiar People Makes its Way Through History and Philosophy

Introduction

This essay offers an argument about what we can call the dispositional tendency of Mormonism. My argument is that Latter-day Saint teachings incline one to a conservative stance toward the world, or at least toward religious faith. This is a claim about dispositions, not political ideology. A disposition consists of the unstated prejudices that exist before ideology, the basic instincts that we use to make sense of the world. Broadly speaking, in modern Western societies there are three dispositions at work. To oversimplify in the interests of conversation, there is a conservative disposition that sees the world through the lens of gratitude, a liberal disposition that sees the world through the lens of choice, and a progressive disposition that sees the world through the lens of liberation. Because dispositions consist of habits and prejudices, not intellectual systems, no person’s disposition consists solely of one of these approaches in any pure and consistent way. Accordingly, in this essay dispositions are offered as a kind of ideal type for our habits and prejudices.

In support of my claim that Mormonism inclines toward a conservative disposition, I will offer an analysis of the Latter-day Saint concept of God and the Latter-day Saint reading of the Fall and God’s covenant with Israel. These subjects are chosen because they are striking and suggestive, though they cannot, taken together, be said to constitute even the whole of Latter-day Saint theology, let alone Mormon history and practice, all of which participate in the making of a disposition. Hence, the argument here can only be suggestive and not demonstrative. Furthermore, it must be remembered that Mormonism will be but one input, and often not the most important input, of any individual Latter-day Saint’s disposition. This is not an essay in psychology or political science, but an attempt, however limited, to get at some of the deep intellectual tendencies of Latter-day Saint thought.

We all have a basic orientation or disposition. We might think of a disposition as our basic set of assumptions about the world. These assumptions aren't simply intellectual or even primarily intellectual. They are also emotional, spiritual, and even aesthetic. Our disposition is the sum total of our prejudices. By prejudices, I don't mean a set of irrational and odious beliefs. Rather, I am using the term more literally. The root of prejudice is the Latin word “iudicere,” meaning “to judge,” to which a prefix is attached. A prejudice is thus that which comes before judgment. Our prejudices are the framework that makes judgment possible. This does not mean that they cannot be examined or reconsidered. Rather, my claim is that there is no point at which we begin thinking without our prejudices. They always orient us.

This is an essay about dispositions. My argument is that Latter-day Saint theology pushes towards a conservative disposition. Another way of putting this point is that Mormonism has a set of conservative prejudices. It might be possible to construct a more elaborate political theology based on Latter-day Saint doctrines, but I am skeptical of the value of such projects. Hence, my project here is more modest. At the same time, it is potentially more ambitious if, as I suggest, our dispositions and prejudices necessarily structure our thinking, providing a shape to our thoughts prior to any explicit reflection. It also implies that Mormonism will necessarily sit uneasily with rival dispositions, in particular, what I shall call liberal or progressive dispositions.

A Conservative Disposition

What do I mean by a conservative disposition? At the heart of the conservative disposition is the sense that one has received something precious from the past that ought to be protected from destruction. Conservatives are distrustful of violent change. Chief among those precious inheritances are the communities in which we find ourselves. Families, neighborhoods, and nations are all precious. A distrust of change does not presuppose hostility to all change. A conservative disposition, however, prefers incremental and marginal change to wholesale or revolutionary change. The evolutionary and the organic is better than the rationalized and the novel. Communities are not simply something precious to be preserved; communities constitute us – we are never really independent individuals. We cannot be who we are without our histories and our communities. We identify with others, not simply because of sympathy but because they are part of a “we,” a “we” without which “I” cannot exist. This creates a certain vulnerability. Attacks on communities can be attacks on our identity. It also creates a certain robustness of the self. To see one's identity as tied up with a rooted community is to be rooted oneself. To know where you come from is to know who you are, and that knowledge renders the self less exposed to corrosive anxieties over identity and place in the world. Coupled together, the conservation of that which is precious and the intertwining of identity and community yield a disposition towards time and persons. Key to the conservative disposition are ideas of forebears and descendants. At the most primal level, this is literal and genetic. We are a balance between past and future. In a sense, we are a conduit by which gifts pass from grandmothers and grandfathers to granddaughters and grandsons. This sense of forming a connection between the past and the future, however, extends beyond kin and family. Although family and kin occupy a special place in the conservative disposition, those precious things that we have, whether they be traditions, communities, institutions, nature, or material prosperity, are bequeathed to us from the past. We enjoy far more than we could create for ourselves, and that which we enjoy is the laborious creation of previous ages, easily destroyed. It is to be conserved, not simply to be consumed and enjoyed, but to be passed on to those who follow us.

Finally, the thickly embedded self of the conservative has a particular disposition towards authority in its most primal sense. Authority is something that arises outside of the self. It arrives from someplace else and makes demands on us, disciplining our lives. We owe debts to the past, to the future, and to our communities. These debts are not self-imposed. Rather, we inherit them at birth and carry them throughout our lives. They are never fully discharged. The weight of these debts is not a form of tyranny or oppression. Rather, they arise from the nature of human life itself. To be a person is to be subject to the claims of authority. We are not naturally free, if by free we mean the absence of duties and obligations.

A Liberal Disposition

The content of a conservative disposition can be illuminated by contrasting it with what we might call a liberal disposition. The liberal disposition begins with free individualism. Everything follows from the prejudice that what is good in life is for the individual to own herself and to chart her own destiny. Where the conservative sees the world first as containing precious inheritances to be saved, the liberal looks out on a world filled with choices, and she experiences herself as possessed of the power to pursue those choices. To inherit something is to receive a gift, but it is a gift that one cannot reject without a certain violence. The conservative is thus in possession of certain precious things, but they also weigh upon him. In the liberal ideal, we possess only what we choose to possess, and its value to the individual arises precisely because it is chosen. The liberal appreciates community, but the communities that most appeal to the liberal imagination are those that are intentional and chosen. Ideally, we choose our communities rather than being born into them or thrown into them by other accidents beyond our control.

The liberal disposition therefore reverses the relationship between individual and community from that in the conservative disposition. For the conservative, individual identity takes its shape and content in large part from communities. As Aristotle suggested, we are constituted by our polis. In contrast, the liberal insists that, properly speaking, the individual is primal and communities are constituted by the choice and deliberation of their members. For the liberal disposition, consent is the ultimate source of authority and obligation. Philosophically, this manifests itself in social contract theories that seek to explain the claims of community in terms of some original agreement. It is also manifested in what can be called philosophical contractarianism, in which one discovers the scope of all moral obligations by imagining what rules of conduct would command the universal consent of free and rational individuals. In effect, contractarianism expands the social contract argument to include not just political authority but all forms of ethical obligation.

The emphasis on the choice of free individuals also yields a different attitude towards persons and time. The prototypical form of human obligation is contractual. We owe to others an obligation not to interfere in the scope of their ability to choose. But our obligations do not arise out of our membership in unchosen communities. Certainly, one's forebears impose no obligations. We cannot be said to be responsible for or to anyone based on actions taken by others before we were born. We may have obligations to the unborn, but only the obligation not to undermine their choices. The liberal disposition, however, doesn't feel obligation to descendants because they are ours, an extension of the unchosen web of community that defines our identity.

Finally, liberalism has difficulties with the idea of authority. Social contract stories seek to justify a spare form of political authority. The assumption of such stories, however, is that authority is presumptively illegitimate. To be morally permissible, authority must always be generated from within the individual. Behavior that is self-regarding or, in the more contemporary formulation, behavior that is not related to maintaining the conditions of meaningful individual choice, is beyond the reach of any moral evaluation or disapprobation. Where a conservative disposition sees authority as a claim from beyond the self that disciplines choice, for the liberal, claims to authority unrooted in the self and its choices are the sine non qua of illegitimate oppression.

A Progressive Disposition

What we might call a progressive disposition consists in the exaggeration of liberal tropes. At the heart of this disposition lies the hope of liberation. Liberalism grounds communities and obligations in the choosing, contracting self. The liberal is thus quite optimistic about the self and its capacities. The liberal disposition finds it easy to believe in the existence of a self with desires and plans worthy of respect. Likewise, the liberal self is assumed to have the ability to choose in meaningful ways among plans and desires. The progressive disposition shares the liberal assumption about the priority of freedom and choice, but it is haunted by anxieties about the capacities of the self. One way to think about the progressive disposition is that it has liberal dreams but conservative nightmares. Where the conservative disposition sees in the situated self a source of meaning, identity, and authority, the progressive disposition sees oppression so long as the communities fail—as actual communities always do—to instantiate a just society. The embeddedness of the self is particularly insidious because it suggests that our ideas and desires, the apparent grounds of personal autonomy, are, in fact, infected with odious injustices. Likewise, our apparently free choices result from accidents of birth and history that may be dictated by the happenstance of past and present evils. At the very moment when the liberal feels greatest ease, freely choosing to act in accordance with self-formulated plans, the progressive feels anxiety and fears the legacy of oppression.

The liberal disposition can take a moderate attitude toward time. To be sure, the liberal disposition sees progress from an illiberal past, but she can imagine a future in which we live freely in consensual communities. For a progressive, history has a stronger sense of motion. The past is an oppressed country, and tradition is likely simply the agent of oppression invading the present. Because true freedom requires not just consent but a just society in which the choices of the socially constituted self can be respected free of anxiety, the work of liberation is never complete. There are always new fronts in the battle for freedom and justice, because the mere absence of coercion is insufficient to vouchsafe liberation. Taken to extremes, the progressive disposition may be drawn to radical or even violent political utopianism, but like any other disposition, progressivism is seldom taken to its logical conclusion.

A progressive disposition can also manifest itself as constant skepticism about, and opposition to, the received structures of oppression. While a progressive disposition need not become utopian, the ethos of constant striving for the always receding promise of a better world generates a distinctive stance towards authority. First, the idea of traditional or communal authority becomes incomprehensible or pernicious. Indeed, such a notion of authority is one of the chief evils against which the progressive feels called to struggle. This does not mean, however, that the progressive accepts the liberal idea of authority arising from consent. There are too many ways in which history and society can taint consent. Rather, authority rises from the process of liberation itself. Those battling on the frontier between liberation and oppression can claim authority because only in the struggle of liberation can the anxieties of omniscient oppression be muted.

These sketches are simplified and overdrawn. I have called them dispositions, but they aren't accounts of human psychology. Rather, they lay out common sets of assumptions about how one might approach the world, especially the social and political world. This is not to say that everyone would articulate their assumptions in this way, or that those with what I am calling conservative, liberal, or progressive dispositions couldn't articulate them in different ways. Likewise, actual character and belief are complicated. We are seldom, perhaps never, wholly one thing or another. We are likely to have intuitions and impulses that could take root in multiple dispositions. There is no a priori reason that our assumptions and prejudices are consistent and coherent. Indeed, it would be surprising if they were.

All these caveats aside, however, I think that many—perhaps most—people in modern societies gravitate more toward one or two of these dispositions. Hopefully, they seem familiar to the reader, and she recognizes them in herself and in those she knows. Their value lies not in their ability to describe the beliefs of particular individuals, but in their ability to render explicit what is often implicit, and thereby form a starting point for examining our beliefs and actions.

Restoration and Revelation

Mormonism begins with revelation. In the early 1830s in Kirtland, Ohio, Joseph Smith and his associates established a School of the Prophets. The name was taken from the Bible, and its purpose was to instruct new converts not only in theology but in secular subjects as well. The project produced the Lectures on Faith,1 which provided a systematic exposition of Latter-day Saint principles, beginning with the nature of God. Today, the Lectures on Faith are little read by Latter-day Saints, much of their theology having been superseded by Joseph Smith’s subsequent revelations. They do, however, contain a striking passage that illustrates the way in which the Latter-day Saint emphasis on revelation shapes one's approach to God and the world. The Lectures begin with a chapter on the nature of belief, followed by a chapter on the character of God. Each chapter ends with “Questions and answers on the foregoing principles.” To the question, “How did men first come to a knowledge of the existence of God so as to exercise faith in him?” The text responds with the biblical story of Adam and Eve in the Garden conversing with God, their fall and expulsion from Eden, and God's further conversations with them in the lone and dreary world. The resort to the Genesis narrative is unsurprising for authors writing in the biblically soaked culture of religious enthusiasts in 1830s America. Furthermore, the questions and answers in the Lectures seem to have been designed to provide prospective Latter-day Saint missionaries with proof texts from the Bible to be used in the public debates that formed such a central part of nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint proselytizing. Interestingly, in the passage that follows the questions and their accompanying scriptural stories, the book states, “What is the object of the foregoing? It is that it may be clearly seen how it was that the first thoughts were suggested to the minds of men of the existence of God, and how extensively this knowledge was spread among the immediate descendants of Adam.”

To see the import of this passage, compare it to the argument made by Rene Descartes in The Discourse on Method. Descartes' ambition in that work is to provide a sure foundation for knowledge by subjecting all of his beliefs and perceptions to the acids of systematic doubt. Eventually, he falls back on the famous “cognito ergo sum,” the undoubtable proposition that “I think, therefore I am.” Having escaped utter skepticism, however, Descartes still feels himself trapped in a position where even the basic data of sense perception must be dismissed as unreliable. Descartes finds his escape in God. Looking within his mind, he finds there the concept of God as an inherent part of his mental architecture. From this concept, he proceeds via a variation on Anselm's ontological argument to the conclusion that God exists and that he would not permit us to be systematically mistaken. Notice that in Descartes’ argument, the concept of God is a basic feature of the individual mind, and that mind is automatically equipped with the resources to generate a proof for God's existence, unaided by anything else. For Descartes, religious belief is thus a sort of implication of his own intellectual self-sufficiency.

For the Lectures on Faith, in contrast, religious belief is a gift. There is no suggestion that unaided human reason will arrive at a proof and belief in God. Indeed, even the first thought that there might be a being such as God comes because he reveals himself. Mormonism rejects the notion of God as a metaphysical origin for existence. Rather, he organizes matter unorganized and inhabits a universe filled with co-eternal intelligences who can neither be created nor destroyed. This vision of a God that exists within a metaphysical frame, rather than outside of it, has implications for Latter-day Saint spirituality. First, it forms the basis for a personal relationship with God, one that promises not simply a subjective experience with a transcendent divine but what Joseph Smith called “sociality.” Like Adam, we can hope to walk with God through the Garden in the cool of the evening.

Alfred North Whitehead observed that “The God of the philosophers is not available for religious purposes.” The God of Mormonism, however, emphatically is available. Indeed, in the view of some critics, he is too available, and a deity shorn of metaphysical transcendence ceases to be an object worthy of religious devotion. An implication of the finitistic God of Mormonism is that his existence is not a necessary truth. God is a being that happens to exist and might conceptually not exist. This doesn't mean that one believes that human reason is unable to formulate arguments for God's existence. Latter-day Saint finitism isn't a form of fideism, declaring belief in the absence of any justification for belief. With Peter, Latter-day Saints are ready “always to give an answer to every man that asketh the reason for the hope that is in [them]” (1 Pet.3:15). The answer they give, however, does not lie in a deduction from the nature of their own intellectual existence. Rather, Latter-day Saint answers are always contingent, and ultimately, they are contingent on God's revelation of himself. If the Lectures on Faith are to be believed, the very availability of a concept of God rests on a primal theophany.

Thus for a Latter-day Saint, knowledge of God is a gift in at least two senses. First, it is a gift from God in the first instance because it is only by his revelation of himself that it is available. It is a divine gift, rather than the achievement of individuals reasoning from first premises. Second, it is a gift because the knowledge of past revelations is dependent on a chain of transmission, with each generation passing on to its children knowledge inherited from ancestors. There is also gratitude for the gift of new revelations as the stories change over time, reinterpreted to give meaning in new circumstances. The process of change and evolution, however, is never the individual creation or discovery of something new. Rather, it is a process of adapting an inheritance that is always a gift from the past to be preserved and passed on to the future. Coupled with the idea of revelation are concepts of apostasy and restoration. The primal revelation of Mormonism to Joseph Smith was ultimately the recovery of something precious that was lost. This is true despite the way in which the devotional account of Latter-day Saint origins has shifted over time. Today, Latter-day Saints tell the story by beginning with the First Vision, a narrative in which God announces a general apostasy and calls on Joseph Smith to be his instrument of restoration. The emphasis on the First Vision, however, is a twentieth-century practice. Earlier Latter-day Saints began their story with the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, a forgotten scripture speaking from the dust. Both origin stories hinge on the recovery of what was lost or corrupted.

Joseph Smith spoke of Mormonism as a force to revolutionize the world. Speaking in the generations after the French Revolution, the word could mean something like violent and radical change. It thus seems like a liberal or progressive gesture. However, there is an older meaning of the word revolution that is perhaps more apt. As Hannah Arendt has pointed out, revolution literally meant a turn, as in the revolution of a wheel on its axle or the globe on its axis. A revolution thus noted a massive change, but one that involved a return back to something that was lost. Hence, for example, the seventeenth-century theorists of English revolution conceptualized the struggle against royal absolutism not in terms of the abstract rights of man but as a recovery of the lost privileges of Englishmen. So important was the narrative of a revolutionary turning to the past that when the actual English past failed to provide the precedents required by the present, they felt called upon to invent them.

This older meaning of revolution seems to rest most easily within Mormonism. In Joseph Smith's revelations, the familiar story of progression from the Old Testament to the New Testament is replaced with a cyclical story of dispensations. We learn in the Book of Moses that the whole of Christ’s gospel was revealed to Adam and subsequent pre-meridian prophets as humanity lost or corrupted what had been previously revealed. Hence, the text of the law revealed on Sinai was supplemented by additional revelations not recorded in the canonical Scriptures. The supplemental revelation, however, was not the Oral Law of the Talmud, but rather the Christian gospel in its native purity, a gospel that, because of subsequent disbelief and apostasy, was lost. To be sure, at times Joseph spoke of mysteries to be revealed that had been hidden from the foundations of the world. But far more commonly, he presented revelation as the recovery of a lost past, whether in the form of golden plates, Egyptian papyri, or even in some cases ancient texts revealed without the physicality of any ancient objects.

Even the discontinuity between apostasy and restoration can be overstated. For all of the rather pointless wrangling over whether Latter-day Saints are “really Christian,” Joseph and his revelations unquestionably operate within the Christian tradition. Mormonism is very far from being entirely the creation of revelations restoring lost materials. Most strikingly, it is utterly dependent on the Bible, whose stories it integrates, interprets, and reinterprets. Nor is the Bible its only point of continuity with the Christian tradition.2 While largely devoid of formally trained theologians, and sprinkled with thinkers that are not always fully conscious of their intellectual debts, the Latter-day Saints have defined themselves in large part using concepts from the Christian theological tradition, even as they have adopted and changed those concepts, often in the give and take of religious polemic. Likewise, scholars have noted that the ecclesiological language of Joseph Smith's early revelations assume continuity with the Christian tradition. Contemporary Latter-day Saints assume that when Joseph’s revelations speak of “the church,” they refer specifically to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In Joseph's early revelations, however, the Lord speaks of “my church” as an already existing body before the formal creation of the Church of Christ on April 6, 1830. In other words, the revelations used the term “church” to refer to the whole body of Christian believers, rather than to any particular institution. This usage is foreign to contemporary Latter-day Saints, but is a well-accepted part of traditional Christian discourse, one that emphasizes the continuity of Christian practices and communities.

Latter-day Saint writers have a tendency to talk about the Restoration and the founding revelations of Mormonism in terms that emphasize their novelty, their radicalism, and their discontinuity with the past. In part this is just good history. Early Latter-day Saints often came from the ideological fringes of sectarian Protestantism, and they were likely to be people disenchanted with their religious heritage. They were seeking “the gifts of the spirit,” new, individual religious experiences. It is also precisely the anxiety sparked by the Restoration’s continuity with the past that often leads Latter-day Saints to emphasize the novelty of Mormon revelations. Only if the Restoration is new can its claims to divine authority be maintained.

Finally, Latter-day Saints of a progressive or liberal disposition are fond of casting the Restoration in more contemporary revolutionary terms because they have a natural prejudice against continuity and the past. Joseph Smith's teachings are appealing as much for their iconoclasm as for any ideas he produced. Progress requires iconoclasts fearlessly breaking with the past, and to cast Joseph Smith and the Restoration in these terms gives one's religion a certain progressive respectability. This need for ideological respectability is perhaps most acute for progressive Church members in the United States, where contemporary Latter-day Saints are most likely to be found involved in center-right or right-wing politics.

There is a sense, however, in which such academic, apologetic, liberal, and progressive reactions are external to Mormonism. This doesn't mean that they are mistaken or inauthentic, only that they are missing something important. The historian sits on an academic perch and pokes at and opines on Mormonism as a social phenomenon, but academics, as academics, do not inhabit the cosmos that Mormonism creates.3 An apologetic stance also fails, perhaps ironically, to fully enter into the Latter-day Saint world. The apologist stands at the borders of the kingdom, defending it against a hostile world. He faces out, operating in a world where the truth claims of the Restoration are under constant pressure and must be defended to the critic or the doubter. Like the historian, he is doing necessary and honorable work. However, apologetics by definition must treat the object of its apology as up for grabs, and thus never has the luxury of simply accepting the faith and working out its meaning. The progressive reading of the Restoration as an iconoclastic revolution enters into Mormonism but does so only shallowly. It sees the important fact as being that Joseph Smith and the Restoration are a break with their surrounding culture and history. The emphasis on the break, however, is driven mainly by the need to assuage progressive anxieties. The anxiety isn't social.4 Rather, it flows from the sense that to be truly right and good, something must be progressive, an agent in the struggle for liberation. If one has a progressive disposition and one loves and values one's Mormonism, it is natural that one should cast it in progressive terms. The shallowness of the reading is ultimately a gesture of love and faith.5 If one fully enters into the Latter-day Saint cosmos, however, Joseph Smith is not an iconoclast, and the Restoration is not a break from the past. Rather, they recapitulate a tradition that goes back to Adam. It is a tradition in which divine knowledge is a gift, rather than an individual intellectual achievement. Our role is to treasure this gift, protect it, and deliver it intact to the next generation. The only revolution is the return of lost things, the recovery of ancient wisdom. This is not a message of liberal self-sufficiency or progressive struggle towards liberation. Rather, it is a story of conservation and recovery, a story of redemptive conservatism.

It is, however, a cosmic story, and one might therefore point out that it lacks an attachment to a locality, or an actually existing tradition. This is a fair point. What is striking about Joseph Smith and the early Latter-day Saints is how rapidly they sought to attach this cosmic story to a particular place and make it the story of a particular people. Latter-day Saints gathered to build Zion. In gathering, they made themselves a people, and the cosmic story of dispensations and restorations became their story, an ancient tradition provided for a new people. Likewise, the ambition of Latter-day Saint missionaries is never simply an individual conversion. Rather, ideally, every convert baptism leads to the temple and the foundation of a new Latter-day Saint family redeeming its dead and passing the gospel to its children. Strikingly, while the language of novelty and revolution has wide currency among Latter-day Saint intellectuals, historians, apologists, and progressives, in the vernacular of Church teachings and practices, we nest the Latter-day Saint past in the language of divine patterns and gratitude. Modern Saints follow in the footsteps of God's people throughout history, and the founding generations of Mormonism are more likely to be honored as the testators of a precious inheritance than as revolutionaries whose iconoclasm is to be emulated. A similar tendency toward a conservative disposition can be discerned in Latter-day Saint stories of the Fall and ideas of covenant.

Social Contracts

In the beginning, man lived in the state of nature. Thus far, the stories of Genesis and social contract theories track one another. Both appeal to a primal era. In this primeval state, humanity lived differently than they do today, somehow more naturally. One imagines that both Eden and Locke's state of nature contained few cities and a great deal of foliage. They both imagine humanity operating in a normative universe quite different than the one we inhabit today. The stories are meant to explain how we got from there to here, and in doing so, they promise to reveal the deep structure of our obligations and rights. Thus far, they are the same. From this point forward, however, they diverge. For the contract stories of Hobbes and Locke, life in the Garden is poor, nasty, brutish, and short, although the Hobbesian Garden is much more brutish than the Lockean one. Both of them see the pre-normative state of nature as a place of endemic conflict with no central authority to promulgate laws and see to their enforcement. Humanity is left to its worst angels. Again, Hobbes presents a more violent and anomian world than Locke—the English Civil War having been a bloodier affair than the Glorious Revolution —but both assume that social obligations and institutions to enforce them are necessary to escape the violence and potential chaos of the Garden. Ultimately, they conclude that individuals in the state of nature would agree to a set of rules and institutions limiting predation and securing peace and protection. Hence, by contract, humanity leaves the Garden and creates society.

The English social contract theorists take it as axiomatic that if we can show that the origins of social institutions lie in agreement, then the institutions are legitimate. Indeed, this assumption continues among many modern philosophers, all of whom reject the idea that Hobbes or Locke provide anything even remotely resembling an accurate account of original human societies. Many of them agree, however, that under ideal circumstances, agreement to a set of norms provides a justification for those norms. Thus, John Rawls has famously argued that if a set of political institutions would be agreed to by agents in an idealized “original position,” then those institutions are just.

The idea that contracts are legitimate because they are agreed to by contracting parties is actually of relatively recent vintage. For example, it did not become the central organizing principle of the law of contracts until the late nineteenth century. Prior to that time, contract law was organized around the assumption that there were a number of consensual relationships—sale, hire, lease, bailment, etc.—each with its own set of rules that were socially imposed rather than individually authored by the agreement of the parties. Likewise, the principle that moral obligations are created by the agreement of the parties, which seemed self-evident to Hobbes and Locke, was deeply puzzling to earlier thinkers. The late scholastics gave the question the most thought. Agreement and promises seem to create moral obligations from nothing. I have no obligation to go to your dinner party, but if I agree to go to the dinner party, I have become morally culpable if I do not go. Such ex nihilio creation of moral requirements seemed the proper preserve of God—a suspect, Ockhamist God at that—rather than man. They concluded that the bare fact of agreement created no moral obligation. A criminal who breaks his promise to murder commits no wrong. Rather, agreement creates an obligation only if it aims at some laudatory end. It is the end and purposes of our agreements that create contractual obligations, not the bare fact of our choice. The difference between the social contract theorists and the late scholastics is more than merely semantic. For the earlier thinkers, we inhabit a moral universe that cannot be reduced to individuals and their choices. For the scholastic theorists, obligations arose as a matter of natural law, which in turn rested on the beneficent structure of the universe created by God. In short, we live in a normative world not of our own creation. It was already here when we arrived on the scene, and it is not contingent on our agreement for its authority.

Hobbes and Locke also use the language of natural law, but they mean something very different by it. Their ambition is to drill down to the normative foundations of society, which they conceptualize as ultimately individualistic. The foundations are individualistic because they rest on the agreement of individuals, at which point there is nothing more that can or need be said in their defense. On this view, we have become as the gods, not because we know good and evil, but because we create it.

Covenants

Adam and Eve do not exit the Garden through a social contract. Like the inhabitants of the state of nature, they have an anomalous moral status in the Garden, but it lies in the absence of sin, not in the absence of obligation. Indeed, they come into the Garden burdened with obligations. From the beginning, they are given care of the world and a duty to tend the Garden. They must be fruitful and multiply and replenish the earth. They must obey God's command not to eat of the forbidden tree of knowledge. How one reads the story of the Fall and assigns moral culpability to the characters in the narrative is a complex task with a complex history. Latter-day Saints have much to say on this; most notably, they offer a positive reading of Eve's choice. This drains the story of the misogyny often assigned to it by Christian theologies, but it means God's initial command not to partake is puzzling. Notice that in the Adam and Eve story in the Garden, none of their obligations arise as a result of their consent. Rather, obligations are imposed on them by God, and they never occupy a condition where these obligations are not present. The difference between the story of Eden and the story of social contract is ultimately conceptual rather than historical. As I noted above, social contract theorists don't believe that they are describing historical events. Likewise, the story of Adam and Eve is a highly stylized narrative that is as much about ritual and theology as anything that today we would recognize as history. As the success of Rawlsian philosophy demonstrates, state-of-nature stories, repackaged as the original position, retain their hold because they present a conceptual possibility, namely of a choosing agent bereft of obligation, save those freely chosen. For Genesis, such a vision of humanity is incoherent. To be human is to be a child of God and an inhabitant of his creation, subject to his commands and the demands of his creation. Authority arises not from within the self but from outside of it.

Upon their expulsion from Eden, Adam and Eve entered into covenants with God. Again, the presence of agreement tempts us towards reading obligations through the lens of social contract. The covenant of Adam and Eve with God, however, does not found their obligations to one another or to God. Such obligations already existed, and having left Eden, the problem faced by Adam and Eve is not generating obligations in some kind of a normative state of nature. Rather, Adam and Eve face the problem of sin and redemption. Through the Fall they have alienated themselves from God and offended against his laws. Being mortal and imperfect, they can expect to do so again. God's covenant offers them redemption. It is not a contract between equals that establishes a self-contained normative world defined by subjective choice. Rather, it is a gift. In the scriptures the images used to describe God’s covenant with his people revolve around families rather than contracts. We are adopted by covenant into the House of Israel. God’s covenant with his people is likened to the marriage of a faithful bridegroom to a faithless bride. Through the covenant of the Atonement, believers become joint heirs with Christ. Adoption, marriage, heirship. These are all examples of what jurists call status rather than contract. They each carry a bundle of rights and obligations, but those rights and obligations are not authored by the parties to the covenant. They come attached to social roles that are inherited and whose content has been defined by past practice and tradition. As a gift and a status, rather than a self-authored contract, covenant sits more easily within a conservative than a liberal or certainly a progressive disposition. The logic of covenant trades on the presumed coherence and legitimacy of externally defined roles that make sense of our relationship to God. The imagery of covenant thus rejects the progressive disposition’s stance toward both time and authority.

Conclusion

This is not an essay about politics, at least not directly. Latter-day Saints in the United States tend to identify with the Republican Party and might therefore be identified as politically center-right or right-wing. Most Latter-day Saints, however, do not reside in the United States, and non-American Latter-day Saints are as likely to identify with political parties of the left as of the right. Likewise, even within the United States, a minority of Latter-day Saints identify with the Democratic Party. Furthermore, in the topsy-turvy world of American political ideology, there is often nothing particularly conservative in a dispositional sense about right-wing politics. Regardless, my goal in this essay is not to justify, criticize, or even explain the political allegiances of Latter-day Saints in theological terms. Political behavior has multiple causes, including demographics, economic conditions, geographical location, and even political personalities, none of which are directly related to religious beliefs. It seems an obvious mistake to think that political behavior is determined by theological arguments.

Furthermore, political parties are only indirectly vehicles of political thought. In a democracy, they ultimately exist to win elections and coordinate the actions of elected officials. They are vehicles for creating coalitions or advancing the goals of charismatic leaders. In doing this, they may be aided by ideology. Such party ideologies are a kind of political thought, even if a generally degenerate form. In successful political parties, however, ideology will be compromised in the process of coalition building. We often deride our politicians for a lack of principle, but the exigencies of democratic institutions force such compromises upon them. If we accept the legitimacy of such institutions, then a certain flexibility of principles among elected officials is a virtue rather than a vice. It does suggest, however, that creating theological apologia for the Democratic or Republican parties is a fool's errand. Party ideologies aren't produced by a process calculated to generate intellectual depth or coherence.

There is obviously some relationship between dispositions and political ideologies, but it would be a mistake to think that there is a straight line from basic prejudices to a political program. This is perhaps especially true in the current political moment in which political ideologies and coalitions that had remained relatively stable for decades are being reshuffled by populism on the right and an at-times anti-liberal progressivism. Dispositions can also be blended when it comes to political ideologies. Conservative liberalism is a perfectly coherent possibility, as demonstrated by numerous liberal factions in center-right political parties around the world. Likewise, some political ideologies, such as “Red Toryism” in the UK and certain kinds of environmentalism, might best be described as progressive conservatism. One can also make a distinction between personal or political projects and political or legal institutions. In my opinion, societies perform best when conservative or progressive political projects are pursued within the context of liberal political and legal institutions. Both conservatism and progressivism have turned pernicious when they are unshackled by such institutions. On the other hand, liberalism is a poor basis on which to structure personal relationships. This is especially true within families, where obligations often exceed any commitments that can be plausibly ascribed to consent or contract. Certainly, every disposition creates risks. A conservative disposition risks a certain insouciance toward injustice. Liberal prejudices tend toward a flattened vision of human beings and their relationships that often misses important sources of humanity and human meaning. A progressive disposition can tend toward a destructive disdain for traditions and communities that can appear in the progressive imagination as nothing more than sites of injustice. These possibilities and dangers are worth remembering in those moments when we reflect, as in this essay, on the prejudices that always structure our thought.

With all those caveats, the gospel as taught by the Latter-day Saints is not another option to be legitimized by the awesome normative force of our individual choice. Nor is it a project of perpetual liberation from the tyranny of our situatedness. Rather, it is a gift to be cherished in gratitude from a God to whom we always owe obedience.

This essay is the subject of a Wayfare forum, How Mormonism Sees the World, published May 1, 2025. Please find additional contributions here. This forum is part of the larger Wayfare project How to Think Politically.

Nate Oman is the Rita Anne Rollins Professor of Law at the College of William & Mary whose thoughts on Substack about the world, mostly about law, politics, religion, and books can be found here

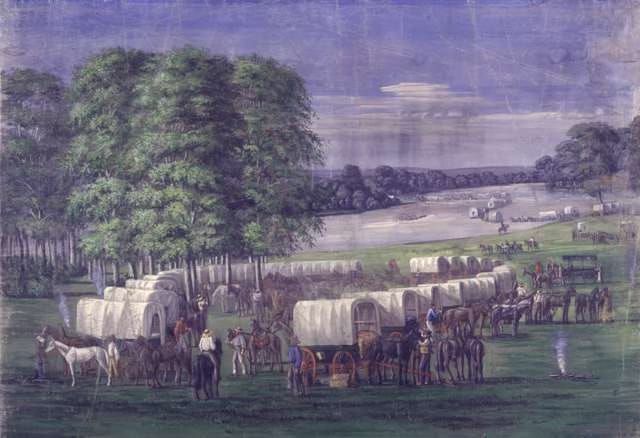

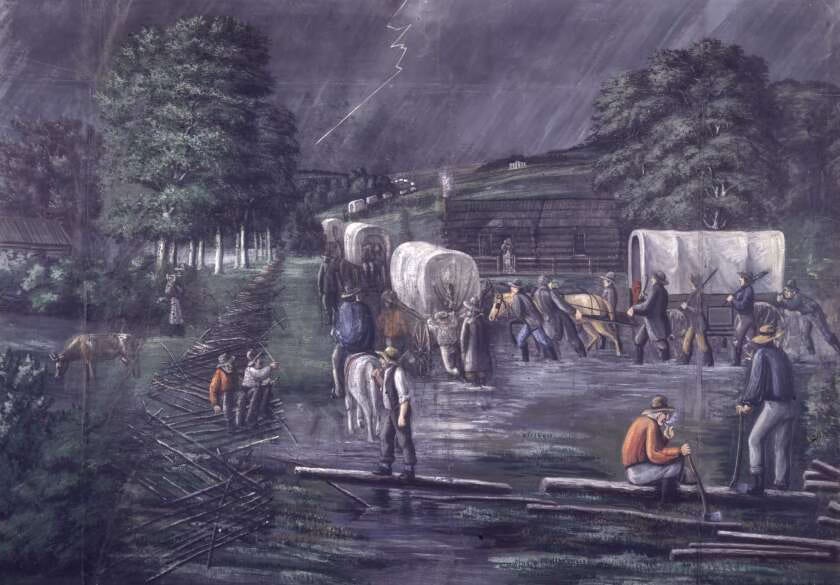

Art from Mormon Panorama (1878) by C.C.A. Christensen (1831–1912).

The authorship of the Lectures on Faith has been the subject of a lively scholarly discussion. Traditionally, Latter-day Saints have assumed that Joseph Smith authored the lectures, but modern scholars argue that they were in whole or in part written by Sidney Rigdon. Until the early twentieth century, they were printed in the Doctrine and Covenants and accepted as one of the standard works of the Church.

Terryl Givens and Fiona Givens deserve credit for this insight.

I don't mean to imply that historians of Mormonism cannot be faithful Latter-day Saints. Many of them are. Rather, my claim is merely that the academic discourse of history never enters fully into the intellectual world of Mormonism. To do so would be to forfeit its claim to be academic discourse.

Although it may be. Fitting in as a Latter-day Saint and therefore a presumed reactionary in a progressive social milieu is not always easy, as I can attest from a professional lifetime in such spaces. It’s natural to use all the rhetorical resources at one's disposal.

One might also point out that it is also, for that reason, incoherent in some sense. To love Mormonism as a tradition is ultimately a conservative rather than a progressive gesture, even when the reasons for the love of the tradition are cashed out in progressive terms. This incoherence isn't necessarily a vice, of course, as any individual disposition will contain competing and inconsistent impulses. It is ironic, however, and a testament to the allure of conservatism as much as of progressivism.