The geese didn’t make sense. I spotted them in passing from my car window, Canada geese strutting on dead grass—and they left a spike of dread in my chest. Were they supposed to be here? Shouldn’t they have all migrated south by now—wasn’t that what geese were famous for? I had read about the current biodiversity crisis for the first time over Christmas break, and as I returned to Utah for my final semester of college, I was thinking about what I could do to help. Now it seemed the world I had only just decided to commit myself to was already unraveling, undone by the newly ordinary sight of Canada geese relaxing in a park in the middle of winter.

Two books and two flocks form the inciting incident of this story. The first flock you’ve already met. The first book, the horror novel Annihilation, was the reason I had been spooked into learning about the biodiversity crisis over Christmas break. I discovered the second book when I got back to my apartment, popped open my laptop, and tried to research geese. I found myself in front of a PDF of Let’s Go Birding!, written by one Ted Floyd, editor of Birding magazine. A cheery quick-start guide to birdwatching, it positively vibrated with Floyd’s enthusiasm. I was supposed to be researching geese, not picking up a new hobby, but the book drew me in.

And then, after only a few pages, Floyd brought me up short. “Stop reading this little book right now. For real. Stop reading and go outside.” Start with an American robin, he suggested. And just observe.

The book and the geese together had cast a spell on me, and I decided I would let it carry me just one step more for today. I stepped out of my apartment and started walking. The day was warm, the streets still lightly dusted from a recent snow. Turning down a new street, movement caught my eye. I looked up—

And there, hopping on a gutter among dripping icicles, were the most unexpectedly stunning creatures I had ever seen. With clever black masks underneath cheery crests, their bodies were buffy tan on top with a yellow belly, ending in graceful coattails of gray and black wings tipped in red. And there wasn’t just one, but a flock of six or seven of the robin-sized birds, hopping between the rooftops and the trees, chattering with each other in friendly whistles, entirely oblivious to the fact that I was standing there on the sidewalk with my mouth hanging open.

“Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing?” Jesus said. “And one of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father” (Matthew 10:29). Or, as a recent stake conference speaker put it, God knows where every sparrow will lay its head to rest tonight. Whereas I had just barely noticed the geese in the park, or learned that these birds on the rooftop even existed, creatures for whom I had no name. It was as if, after holding back for so long, nature had suddenly decided to spill all its secrets at once and had sent this troupe of adorable little bandits to invade the room where I had all my life plans carefully arranged.

Where they promptly started smashing all the furniture.

When I got back to the apartment, I learned that Canada geese had figured out that they didn’t have to bother to migrate if they could find a nice spot of mowed grass to relax in. I also learned that the rooftop robin hoods were called cedar waxwings. Ted Floyd’s book explained that birders had a name for that kind of dazzling first contact: spark bird. Before I closed my laptop for the day, I had ordered a pair of binoculars and a field guide.

The worm of worry remained inside me, but now I had a plan. When the earth was finally put together, “God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good” (Genesis 1:31), yet I had just learned through direct experience that I knew very little about what made the earth good. If I was going to figure out what God might have us do about our compounding ecological crises, I would have to start seeing the world for the first time. Not just learning about it, but experiencing it, trying to soak in with my own eyes and ears the reasons why God so loves it. Birds seemed like a great place to start.

As if, now that I’d seen a cedar waxwing, I could ever go back.

BIG YEAR

Birds—would you believe it—were everywhere. It turned out that any time I set out with my binoculars, I was bound to discover something I’d never seen before simply because I’d never bothered to look.

There were of course the urbanite birds: plucky robins, workaday house sparrows, raucous scrub jays. But I was also astounded at how, with very little effort, I could drive to a golf course or an industrial pond or the foot of the mountain to see the kinds of creatures that I thought were only supposed to appear posing in Audubon paintings: great blue herons, egrets, Steller’s jays, sandhill cranes.

My favorite haunt became a path along Utah Lake only fifteen minutes from my apartment—Skipper Bay Trail, according to my freshly downloaded birding app. Soon I was visiting several times a month, and nearly every time I went, there was something new to see. Red-winged blackbirds swaying on the tips of the grass in the warmth of the sun. Flycatchers and kingbirds swinging to and from their perches to nab insects mid-flight. Black-billed magpies pranking each other in the bushes and squawking like squeaky toys. A soaring red-tailed hawk eyeing us all. The torrent of discovery swept me along—pouring down, as it were, from the windows of heaven, such that there was not nearly room to contain it.

There was also a whole new birder language to learn: bins, LBJ, pish, chase, dip. I learned that many birders kept a life list of the different species they’d seen and that each new species was a lifer. A year where you set out to see as many species as possible was your big year. My own life list grew by the dozens. By the time I graduated in the spring, I had seen over forty species. By the end of the year, I would have one hundred and ten.

The more I looked, the more astounded I became. I couldn’t believe that God had toiled over something as captivating as a Virginia rail just to hide it in the marsh grass. Or bothered to dream up something as hilarious as a California quail scurrying across the road. And He hadn’t planned on telling me about any of this?

Except, of course, the birds had been shouting their presence from the rooftops. And as my wonder at the world unfolded, so did my anxiety. Every new species was a new friend, and someone new to worry about, another knot in a tangle of problems. The more I fell in love with birds, the more I needed solutions for them.

TWITCHER

People much smarter than I had been trying to untangle these knots for centuries, so I dove into the best books to discover what they had found. I made quick progress at first, finding the categorical arguments easy to reject. No, the earth was not just made for plunder. No, humanity should not try to pay for its sins by committing mass self-extinction. But my to-read pile grew as long as my life list, then longer, while the answers did not become any clearer. Even the touchstones of environmental ethics that I agreed with emotionally or spiritually always felt too vague and incomplete. The great conservationist Aldo Leopold, for instance: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” The vibes are spot on. I’m still not sure what it means.

The scriptures didn’t have straight answers either, full of seemingly contradictory commands, vague directives, and manipulable guidelines. To take just one well-worn example, the Doctrine and Covenants instructs that the earth—“the fowls of the air,” no less—has been “ordained for the use of man” (Doctrine and Covenants 89:12). When read alongside Genesis’s exposition that God has given humankind “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth” (Genesis 1:26), it’s reasonable to understand why someone could believe the “use of man” to be purely or primarily economic. Yet the Doctrine and Covenants makes it clear that use also encompasses “to please the eye and to gladden the heart . . . and to enliven the soul” (Doctrine and Covenants 59:18–19). Where does that leave us? I couldn’t decide. Constructing a satisfying environmental ethic out of gospel teachings felt like trying to assemble a five-course meal from a pantry full of delicious but contrasting ingredients, some as malleable as rice, others as specific and potent as horseradish and watermelon. When Enoch heard the earth mourn for the filthiness upon it, I couldn’t help but read his pleas to God as his own despair over being at a loss as to what to do. “O Lord, wilt thou not have compassion upon the earth?” he asked repeatedly. “When shall the earth rest?” (Moses 7:49, 58).

My putative ethical reasoning was unexpectedly put to the test when a family of stray cats appeared in the storage unit next to where I parked my car. Someone had set out water for the kittens, and the mother hissed ferociously whenever I got too close. Later, I saw the mother prowling the parking lot and realized with a stab of worry that she was hunting the covey of quail I’d recently discovered hiding in the apartments’ flower beds. I’d seen the chicks running after their parents like dirty cotton balls possessed by magnetic properties. Who was in the right? Didn’t the mother have to feed her kittens? Quail were hardly a threatened species, but weren’t their adorable young just as entitled to life as the cats? Should I try to scare the mother off? Contact the owners of the storage unit and ask them to turn the cats over to a shelter? Call animal control myself? I dithered for weeks. Then, one day, the cats were gone. I realized I hadn’t seen the quail in some time, either.

Meanwhile, the river of new lifers had narrowed to a stream, then a trickle. The kingbirds I’d been so dazzled by at first weren’t as surprising the third, fourth, or fifth times I visited Skipper Bay Trail. Fall migration surged through with a brief blast of fresh air, then it was back to the winter birds: the year-round robins, the juncos, the house sparrows in the usual bush by the hair salon. Discovering new species required further and further visits afield. I felt my attention slipping, the initial thrill wearing away, my desire to act waning because I couldn’t figure out a satisfying direction to exercise it in.

Twitcher is the term for a birder who subscribes to rare bird alert listservs and drives hours to catch a glimpse of an off-season rarity or misdirected vagrant. The title is, if not outright derogatory, a bit of a verbal side-eye, a criticism of a type of bird watching that seems to be nothing more than a sport, a competitive, obsessive hobby rather than a wholesome or merely eccentric one. As fall gave way to winter, I signed up with the Sageland Collaborative, a local conservation group, to help survey rosy finches, an adorable yet elusive species that descends from the Rocky Mountains during the winter as snow swallows up food sources in the higher altitudes. Without better data, experts aren’t sure how the species is faring because of climate change. I flew home to Pennsylvania for Thanksgiving, and rather than sticking around for the extra week or so until Christmas break began, I scheduled a flight back to Utah so I could make sure I met my monthly survey date. At this point the anxiety overcame me that, despite whatever I told myself, I wasn’t doing this for the birds anymore, that the magic I had thought so inexhaustible had disappeared. Maybe I had become a twitcher, and was now condemned to return to a disenchanted life. Or, worse, maybe I had mistaken novelty for astonishment, and there had never been any magic in the first place.

I never did see a rosy finch. The year after, I moved back East for grad school and a new phase of life, trading the scrub jays of Utah for the blue jays of my childhood. Settling in a new place meant new birds to discover, which was exciting. But leaving behind the birds of the West was also clarifying. Looking back, I saw that the wonder, the beauty, the fun of birding had never diminished, even when I’d worried it had. Even when I saw the same birds outside my apartment window every day, I hadn’t stopped loving them, even if I didn’t know what they needed from me.

PATCH

One of the things I love most about the restored gospel is its insistence on improving the here and now, of planting the abstract in the dirt. Or, as Rosalynde Welch put it in a beautiful essay, “if heaven is here, then it’s all low altitude.”

In birdwatcher slang, your patch is a spot that you visit frequently. It can be a favorite trail, a park, a spot by a lake. It can be your backyard. The tiny world outside your window. Except that once you start paying attention to your patch, it never stays tiny. When you slow down and start to pay attention to individual birds, you can’t help but become absorbed. In their movements. Their habits. Their lives, so completely full and apart from your own.

My favorite place to go birdwatching is the backyard of my parents’ house in Pennsylvania, where I grew up. I like to sit in the sunroom and watch the robins. Every summer, they are there. Running in the grass looking for worms. Nodding off in the sun on the driveway. Singing cheerily, cheer up, cheer up, from the trees I climbed as a kid. The juveniles from the year before have returned as adults, and they are feeding new juveniles, just as shaggy and needy as the adults had been last summer. “A small place, as I know from my own experience,” Wendell Berry has said, “can provide opportunities of work and learning, and a fund of beauty, solace, and pleasure—in addition to its difficulties—that cannot be exhausted in a lifetime or in generations.” Is it any coincidence that a robin features so prominently in Rosalynde Welch’s essay? They are the very definition of low-altitude wonder.

When I’m sitting on the sunporch, I trust that better answers to our modern crises will come—whether those crises are social, political, ecological, or spiritual. When I first saw the geese in the park, I needed to know what to do about it. But the most important answer, the most important action, I’ve discovered for myself was to start paying attention in the first place. Not just through education or research or keeping up with current events, as important as those things are. But by watching the same backyard, street, or lakeside trail for five, ten, fifteen minutes at a time.

And when I started paying attention, I realized I had things slightly backwards. Paying attention, it turns out, is not just for gathering the data to solve the problem set of eternal salvation. It is, on some level, salvation itself. “By our attention we gain the world and the world becomes a home,” philosopher L.M. Sacasas has written. “What we get, simply put, is nothing short of the world itself.”

Put differently, a little like grace, the world has already saved you. As a manifestation of God’s love, how could it not? Thus, being in right relation to the world might start with constantly encountering that reality in its solid, little ways. In your patch. Only then will you gain the world. Only then will you encounter the kind of grace that inspires transformation, not out of fear for what you can’t do, but out of love and gratitude for what has already been done for you.

After a bruising first year of grad school, I flew to Utah to visit friends. Despite their love and encouragement, I was stressed, unhappy, worried about the dizzying direction of my life and theirs as we all went our separate ways. I borrowed a car to drive out to Skipper Bay Trail and sat by the side of the lake, watching the birds far out on the water. The birds weren’t new that day. They hadn’t been for some time. But the peace I was looking for found me there in the wind and the waves. I knew it could be the last time I visited the trail for years. Maybe for the rest of my life. But there would be another patch. I would find it.

Jeremiah Scanlan is a fiction writer and birdwatcher, currently studying law.

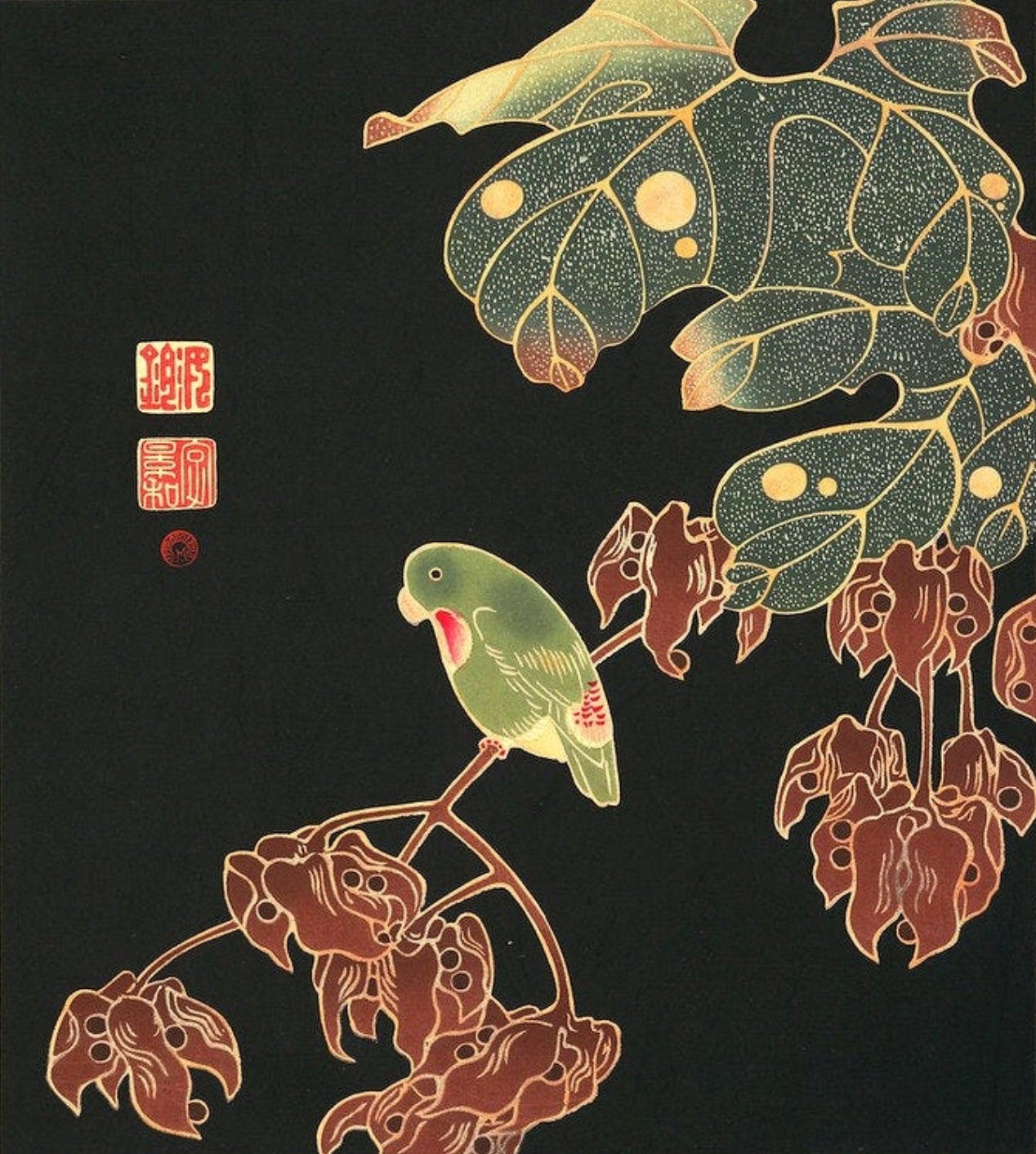

Artwork by Itō Jakuchū.

The Gift Beyond History

John Ciardi flew bomber missions in WWII; later in the war he was posted to a desk and given the task of writing letters of condolences to grieving parents whose sons would never come home. And so he knew what it was to be both an instrument of pain and suffering, and a healer of pain and suffering, in ways more intense than most of us will ever know. A…

The Book of Mormon Storybook for Little Saints: Introduction

Genesis 1:31 And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good. We started this journey shortly after becoming new parents to a beautiful little boy named Clarence. We want Clarence to love scripture stories, not simply because they are scriptural, but because they are beautiful stories with profoundly human characters who are strug…

Thank you for this beautiful reminder to see the grace of God all around us.