Airborne at Low Elevation

Earth is the template for heaven; life here, at low altitude, is the foundation of life there.

APRIL ON THE OZARK HIGHLANDS, the middle of the middle of North America, calls up a riot of life. Every year there appears in the crowded zone between earth and heaven a race of apple-green inchworms that ride the breeze on long strands of silk. Springtime also resurrects an army of dandelions from my lawn; with Sisyphisian futility, I cannot resist the battle. And so it was, one April morning, that I found myself digging in damp earth, close enough to smell its humid breath. An inchworm wafted by, hovering at eye level, and I admired its delicate color. Then a robin passed, gobbling the creature from its silk tether without breaking rhythm.

The moment was funny, and a little sad, and full with a significance I couldn’t quite name. It seemed as crowded with meaning as my vision was crowded with life. The fat robin told God’s good providence, its hunger satisfied without care or anxiety. The worm told passing, the ever-present horizon of our death-bound, animal mortality. The smells on the earth’s breath told time, cycles of decay and growth, death and resurrection, springtimes from the foundation of the world. And I—well, I was there. “This is where everything happens,” is what the moment seemed to say to me, as best I could tell it.

If I were to boil down the meaning of Joseph Smith’s restoration to a single aphorism, This is where everything happens might be my best try. This idea was the engine of the early church’s first migrations. As revelation began to flow, the earth under Joseph’s feet became holy ground in widening circles of sacred geography. The remnant of the house of Israel? They’re here, just down the river. New Jerusalem, site of the second coming? Watch this space, coming soon. The garden of Eden, primordial belly button of the world? It’s here too, in Missouri. Eve ate the apple on the same Ozark highland where my robin ate the inchworm.

If you find a touch of the absurd in this, I agree. We’re accustomed to thinking of the sacred as something apart, exalted. And we have good reason: the roots of the word sacred contain the idea of something protected and removed from ordinary settings, everyday experience. Sacred space is an ancient land, a walled garden, or the top of a mountain, the higher the better. But the restoration introduced a low-elevation version of sacred geography. Right here, at ground level, among normal places and events, sacred things happened.

I hear a twinkle in the divine voice as it relocates the high-and-holy to its new rough-and-tumble neighborhood:

A voice of the Lord in the wilderness of Fayette, Seneca county, declaring the three witnesses to bear record of the book! The voice of Michael on the banks of the Susquehanna, detecting the devil when he appeared as an angel of light! The voice of Peter, James, and John in the wilderness between Harmony, Susquehanna county, and Colesville, Broome county, on the Susquehanna river, declaring themselves as possessing the keys of the kingdom, and of the dispensation of the fulness of times! (D&C 128:20-21)

Broome County, a holy land? Is Saul too among the prophets?

As the Restoration unfolded, these geographic circles extended outward with no apparent limit. A general principle came into view, a kind of axiom of the Restoration: the whole world is holy, because it is where we encounter God. In time, Joseph understood that these sacred circles, always widening underfoot, were both geographic and metaphysical. The spirit world? Look around, it’s here. Heaven? Also here, wherever you are. Eternal life? The people and relationships closest to you.1 For better or for worse, our relational heaven is here and it looks a lot like now, but with the added burden of glory. Good news if you’re a robin, bad news if you’re an inchworm.

Joseph’s life accelerated toward its close, and the revelations rolled toward a full-blown theology of divine immanence, the idea that deity exists inside the universe and its conditions, not beyond or outside. The prophet came to understand a God present in the time and space of creation, not just as an occasional miracle or an abstract omnipresence but in the integral, elemental matter of the world. “The elements are the tabernacle of God,” Joseph declared in a sweeping theological revision of anthropology, christology, and ecology. “Yea, man is the tabernacle of God.” God’s solidarity with creation is a question both of metaphysics and of ordinary physics, of God’s material, embodied being. “God Himself was once as we are now, and is an exalted man, and sits enthroned in yonder heavens!”

For me, it is the revelation on baptism for the dead that brings the restored gospel’s brashest claims into focus. Joseph taught that humans can act as divine agents for our dead, as vicarious saviors. We raise the scaffolding of heaven here and now, welding it as best we can with our weak bodies in the waters of baptism and our slender pens in the record books. Jesus prayed that his Father’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Much of Christian theology has received this saying to mean that earth life is a faint, fallen trace of heavenly life. Latter-day Saint ordinances flip the script. Our temple theology requires that the power of godliness be manifest, counterintuitively, in heaven as it is on earth.2 Earth is the template for heaven; life here, at low altitude, is the foundation of life there. But if heaven is here, then it’s all low altitude. “It may seem to some to be a very bold doctrine that we talk of—a power which records or binds on earth and binds in heaven” (D&C 128:9).

Bold doctrine, perhaps, or depressing. What is human society, what is the natural world, to presume to play host to heaven? Who are we-—poor, bare, forked animals, birthed between feces and urine—to act as saviors on behalf of our dead, to claim that our holy performance frames the foundations of paradise? Is that kingdom of heaven worth seeking? Is low-elevation eternity worth launching?

“This is a faithful saying. Who can hear it?”

“Mormons are specialists in immanence,” John Durham Peters observes. But God’s people have glimpsed divine immanence ever since they addressed him as Immanuel, “God with us.” The books of Exodus and Leviticus tell one overarching story of God’s coming to abide among the Israelites in the sacred tent they built for him. This is the central promise of their deliverance, more than freedom or land: I will dwell among you (Lev 26:11). The promise was given again to early Latter-day Saints in their own exodus and deliverance: I am in your midst (D&C 38:7).

And what is the incarnation of Jesus Christ if not the full-flesh manifestation of God’s immanent presence in the world—in Bethlehem of Judea, to be exact? Jesus didn’t just come down to visit us, he came up from among us. Conceived and born to a mother, raised to adulthood in a time and place and subject to his historical horizon, he lived toward his death in and as a human body. “That which He has not assumed He has not healed,” wrote Gregory of Nazianzus; Christ assumed our finitude to heal it. Alma knew the same thing. Christ performed the central event of cosmic history, the atonement, right here, at an altitude no higher than the cross on which he was lifted.

If there’s little new about the idea of divine immanence, there’s also little new about the way I’ve told it here, as a story of the Restoration’s audacity, boldness, and discovery. We often frame the truth of God’s immanence as a celebration of humanity’s elevated station, of our divine potential for eternal progression, our glorious future. Exultation colors our notions of exaltation. I don’t begrudge this uplifted mood, but I think some ballast is warranted. Is it possible to exult mournfully? To celebrate somberly? The truth of God’s immanence calls us to sober self-revision at least as much as optimism. It’s a story of the worm as much as the robin.

If everything happens here, time and eternity, worlds without end, we’ll have to change our ideas about what is ultimately desirable and good. What is heaven like? Limitlessness, frictionlessness, and changelessness are probably off the table. Constraint, conflict, and loss are probably back on. Gravity, physically and metaphorically, is back on. This is not all bad news! Snowfall, autumn leaves, and inchworms riding the breeze: back on, courtesy of gravity. But so are skinned knees and broken dishes. So are robins. So is the weight of the world. The immanence of God is a weighty doctrine, and we should feel it in our bones.

It’s one thing to contemplate, whether buoyantly or weightily, a heaven that is just like earth—a heaven that just is earth, in all the ways that the prophet Joseph showed us. It’s quite another to get down to brass tacks.

That restoration theology inspires my faith and commands my imagination is the organizing principle of my life. So I want to know: what’s under the hood? Do the details check out? For this, I ask the philosophers. The notion of divine immanence that Joseph revealed in aphorisms, images, and sacred narratives has been the substance of a knotty philosophical problem over the last century or so. When philosophers think about this problem, they ask how to get transcendence out of immanence, the metaphysical equivalent of spinning straw into gold. Is it possible that God could exist under constraints of time or space? Would that God be worth worshiping? Some philosophers believe that art shows how something akin to this question can be answered.3 Art has a way of meaning more than it explicitly says or shows, in the way that my experience with the robin and the inchworm meant more than I could express. We experience immanence, what is here, as containing more than itself, something that transcends itself. To be clear, Christ’s grace is more than an aesthetic effect, and no painting or poem can save my soul. But art provides proof of concept for the possibility that faith embraces: namely, transcendence can find space within the immanent world. Engagement with art and imagination demonstrates how it happens in real time: through my awakening to what is beyond me, to the dimension of ordinary experience that exceeds itself.

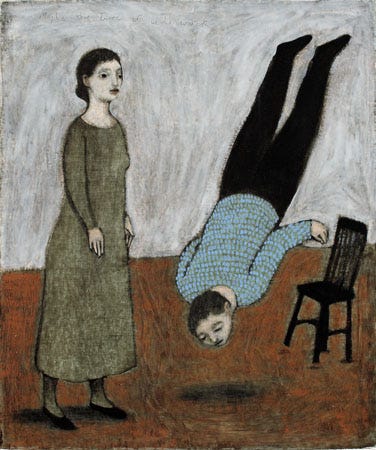

Art’s ability to illuminate the divine in everyday experience rings true to me. Indeed, the most visceral expression of this idea I’ve ever encountered is a canvas painted by Brian Kershisnik that hangs in my home. Inscribed with the words “Flight Practice with Instruction,” it depicts two human figures. One holds a long cord in his left hand and gestures with his right. Just above his head, tethered by the cord at the waist, the other figure flies through a blue-green ether, limbs folded close to his cloud-colored tunic. The flight is graceful within the painted canvas, but the looped cord and curved limbs express compression, closeness. This is not the flight of a hawk. Thick-brushed paint holds the flyer fast in viscous swirls. Teacher and student are trammeled peaceably by the black tether and the close edges of the canvas. They will not rise high above this world. The teacher’s gesture points earthward, and the flyer will soon descend.

This painting captures something essential about my earthbound experience of sacred things. In “Flight Practice,” the black tether holds the flyer close to the earth, the place that is holy because it is where we encounter God. Instructor and student are bound by a strong tie, the sanctified relationships that take me beyond myself, into transcendence. The rough brushwork conveys the friction of mortality, the suffering that calls forth compassion and reverence. The elbow-to-knee composition of the figures crowds me with the world’s availability, a jostling creative abundance inviting me into involvement and care. The earth tones are borrowed from moss and eggshells, life in its elemental transit of death and regeneration at the heart of the Christian message.

Here, not there. In, not out. Down, not up. Close, not far. Fastened, not loose. Skyline, not sky. These are the qualities of the world I cherish, the world where a robin gobbles a worm and eternity shows itself in the April moment. This is where everything happens to me. But don’t be misled: God is in the thing. There is no doubt that even at low elevation, we are airborne.

Rosalynde Welch is the Associate Director of the BYU Maxwell Institute.

Artwork by Brian Kershisnik.

For teachings that the spirit world is located on earth, see Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Brigham Young [1997], 279; for teachings that earth is the site of heaven, see Doctrine & Covenants 88:14–26; for teachings that the condition of heaven is the persistence of relationships, Doctrine & Covenants 130:2.

Samuel Brown develops this idea in his book In Heaven as it Is on Earth, and I borrow his perfect formulation of the phrase here. See Samuel Morris Brown, In Heaven as It Is on Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, USA, 2012).

For one Latter-day Saint philosopher’s careful examination of the question of transcendence in the world, see James Faulconer, “Myth and Religion: Theology as a Hermeneutic of Religious Experience,” in Faith, Philosophy, Scripture (United States: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, 2010), 69-86.

Really enjoyed this! Appreciate the language, the themes, and the passing reference to a line of scripture I love: "Is Saul also among the prophets?"

Also thinking about this:

"Art provides proof of concept for the possibility that faith embraces: namely, transcendence can find space within the immanent world. Engagement with art and imagination demonstrates how it happens in real time: through my awakening to what is beyond me, to the dimension of ordinary experience that exceeds itself."

I've been thinking a lot this year about scriptural interpretation. We've got all this great scholarship, but if all you understand about a Biblical passage is its probable meaning in an immediate historical context, it feels like you're missing the soul. For believers, it feels important to look to scripture as an expression that contains or evokes something extra. Packed words, leaking meanings right and left. God's own collaborative art project.

What a joy to read. Thank you Rosalynde. I will be thinking about this beautifully written essay for a long, long time. It was also fun because you are so like your mother - a wonderful writer!