Rotate the Crops: Crops are for Communities Greater than the Self

An Essay in Three Parts: Part Two

Farming, like faithfulness, harbors no solitary activity, although it surely involves moments of restorative solitude as well as cratering loneliness. Faithfulness to truth might also mean that, in addition to rotating our fields of claims after years of repeated testing, we look for truth in the vibrant material, social orbits, and embodied relations of other people in the world around us. Even the self entails in itself a kind of solipsistic community of conflicting and changing desires. Freud divided the self into the “es,” “ich,” and “über-ich,” intellectually mangled by the Anglicized Latin into the “id,” the “ego,” and the “superego,” while C. H. Cooley let the inner voices reflect on what others think in what he called the “looking-glass self”: I am what I think you think I am. In this second part of the essay on rotating the crops as a metaphor for the art of living, I side with Cooley in caring for communities greater than one in nurturing the growth of truth claims.

Let’s take that most basic unit of more than oneness: for example, what does it mean to be faithful and true to my partner in marriage? More than just two in love, a marriage begins with witnesses and officiators, for faithful partnerships bear truth and fruit more alive than any self: in other words, the truth, or fruit, of our relationship does not necessarily follow some fixed sense of prior truths (whether eternal, society-wide, or relationship-specific), however useful each of those may be in framing and adjusting my behavior to the soil of each situation.

We cultivate true fruits of our relationship by enriching our relationship with meaning greater and more enduring than ourselves. For example, I have no claim to demand what truth I think the origins of our relationship should predetermine about my partner; none at all. We have something much better.

To borrow from Adam Miller’s Letters, my love bears fruit not as I demand her to be part of my story but as I serve and support her story as it grows to ends higher than whatever we currently think our best story together may be. I should stay open to and work for truths in our relationship greater than I can see, for living truth outlives my mortal understanding. In love with my beloved, I choose to serve, evolve, and live in cultivating meaning and truth outside myself, herself, and (whether or not we lift one another) even ourselves.

These parentheses matter: “outside ourselves” might mean that we together become a creative eternal partnership or it might also mean we separate outside ourselves into a sustainable situation. It depends on the parentheses: this commitment to something larger than ourselves, alone or together, holds whether or not we lift one another in the practical soil of everyday fact. This option dignifies and protects those partnerships that, in not lifting one another despite seasonal recommitments, seek higher purposes precisely by separating into social networks greater than a partnership.

The reality of dignified divorce does not undermine—if anything, it underwrites—the fact that any enduring creative relationship that produces lasting fruit must also operate in our risky reality. Eternity has more meaning if I must work to make tomorrow a bit better. Promises do not draw on some past truth. They make the future true not by removing the risk of our future but by enlivening the stakes of their reality today: our relationship may bear fruit worth more than us. (Forgiveness rewrites the past and forms a new present while promises loop the future into the present.)

I do not mean to imply that raising a family together constitutes the only path to bear fruit or last together, although biological reproduction, to stick with the organic metaphors that become reality, could hardly raise higher stakes for the future. In my experience as a father of four, perhaps the only thing more challenging and rewarding than raising children is being one. There are many worthy ways to bear fruit together, with biology only one of them.

Vows bind us to a future harvest that, because we believe in it, brings value in a present potential. (The past, present, and future truth are, while infinitely consequential, never fully fixed to those who enact promises and forgiveness.) We, the couple, charge our future work together with a special hope that, by perennially choosing to remain together, we also rest on the fact that we will never—not now and not then—be forced to be together forever. That freedom over time ensures our efforts, without compulsion, to serve worthy futures greater than ourselves.

Faithfulness to an actual specific person, especially a potential partner in perpetuity, provides an abiding rootedness in the real life work of a lived relationship that may, but does not have to, outlast and adjust to real changes. How better to understand my sexuality, my gender, or any other facet of my life than by its fruits—by my actions in relationship with my partner, our evolving commitments, and their consequences within reflective societies? Keen to listen to, learn from, and protect all those who experience embodied relations differently than I do, I find little interest in applying or amplifying a general vocabulary for sexuality or gender onto others. Personally, I would rather understand my sexuality and gender through my commitment to live faithfully to my partner’s love and life. Because we seek relational, embodied, and grounded love and life with one another, our commitment bears fruit, faith, and growth on truth’s terms, not mine. Therefore, I would be a fool to unlovingly impose my understanding of love onto others. The dignity of practically loving another living person often exceeds public expression; love and tolerance welcomes growth and difference more subtle than a fixed label. By living in the fertile (mucky, dirty) soil of the realities of a beloved, and then by granting charity, attention, and care to those who live in differently embodied relationships, we toil on firmer grounds than we would manage by chasing after the tumbleweeds of fixed categories, desiccated and scattered as they often are by the bitter winds of tradition and whims of prejudice.

Still, public language about bodies and fertile relations should not be dismissed. Categories can bludgeon, obscure, and contain differences but they can also be secondary means for building charity and reflection across differences. By analogy, no student or scholar would label the fields they hope to understand with names that those who tend those fields do not accept; so too should we beware of the corresponding temptation to label people’s bodies and love relationships by categories they do not welcome. Use language to charitably serve others whose practical lives, messy and complicated as all of ours are, already are their own best descriptions. Consider how descriptions others provide may be grown, rotated, and given away into serving still others.

Language offers a means to truth but rarely truth itself. Except for some very special acts (promises, proofs, and poetry, among others), language rarely determines the truth of a case; when used well, language describes and supplements (to use Rousseau's term) the ongoing, shared work of truthmaking. The logic of a single prooftexted statement need not be taken as determining all future truth: the whole fabric of language and literature might be read, reread, and revisited to seek supplementing living truth across many pastures. So, as the verdant social fields sprout new categories, we can welcome, consider, and renew language in ways that serve the good of living people. A reality that sustains the enduring truths of loving relationships will be one in which those relationships are known primarily by their evidence, not prior judgements inherited from brittle categories—no matter how complex or reductive.

How others hear and interpret our language also matters, if only indirectly. Language may not determine truth, but crop rotation, precisely because it must be a collective exercise greater than any one person, has no room for laissez-faire tongues and pens. For free speech to have its value, we must develop speech worth giving away. If anything, the crop rotator moves away from reactive talk based on fixed, prior, piecemeal categories and toward prudent, cautious evaluation of living relationships and the rivers of language that irrigate them. No kind, no category, no particularity of any relationship has a guarantee to avoid real-life struggles or even the horrors of abuse and trauma. Our categories neither protect nor condemn us: rather we do all that by how we live together. No relationship must bear only blessed memory, and thus relationship evaluations should begin and end with lived collective evidence, not assumptions about abstract labels and categories.

Consider by analogy the seasons of Santa. Is Santa true? Is Santa real? Is Santa good? These questions—or perhaps better, this single question—are best answered by looking forward to the live situations and fields in which we may ask questions, not backward to Santa’s priors. A young child may be enchanted to do good by Santa’s magic just as a growing child may profit from learning that Santa—that chimney-shimmying, bearded red man riding a reindeer chariot at warp speeds—cannot be literal. Later that literal negation may mature into the adult affirmation that Santa’s charitable spirit of generosity and serving others lives on as more real than most everything else in life, even the surplus commercial consumption Santa culture justifies after every autumn harvest in the northern hemisphere. Santa cycles with the seasons of life!

The truth about Santa, then, is no food storage gathering dust on a shelf; it lives, grows, and evolves in seasonal and life-cyclical relationships that matter and do real work in the slow-growth forests and fields of grounded patterns, probabilities, life arcs, and rooted realities.

As the farmer knows, a choice integrated over many harvests between continuity and change develops a third option: “both-and under specific conditions.” In the words growth and learning, prudent rotators see two words for how many either/or propositions become specified, not generalized, into both-and truths over time.

In other words, the truth or falseness of Santa holds as nothing general. It holds as a specific truth claim in the light of growth and learning: namely, over the arc of a lifetime, Santa may be good for the young child, literally false for the youth and disenchanted adult, and then even more than real for the generous maturing actor who gleans and shares in action the sweet fruit of the Christmas spirit. Each position grows true in turn and rarely at the same time and place. (Others may see it still differently. By adding variety and color, they strengthen this observation: rotators permit truth to sprout where it will.) Overstrong assumptions that all truth must be either brittlely fixed or flabbily relative often miss the mark of time itself: specific, contextualized healthy growth and seasonal decay over time is truth. What beliefs about Santa could be healthier and truer? Take the question as an invitation, not an evasion, to consider specifics. The spirit open to such beliefs (whatever they may be) gives generously beyond any season.

Crop rotators, while comfortable in such mature complexities, are also comfortable rooting out semantic senselessness, or language that does no good work. Again, language does not fix or flex arbitrarily to one’s will; nor are its middle ways all good or bad. The commonplace notions that truth should be either categorically fixed or acrobatically relative are funhouse mirror images of one another. They both follow a perverse and popular misunderstanding: namely, that a single person alone suffices to possess the truth. What obvious bunk. Ideological dogmatism and total relativism are not opposites—they are the conjoined twins of the same wicked selfishness that truth could ever be mine alone.

How profoundly impractical would it be to live as if I believed that, without a permanently fixed sense of truth, nothing but one thing would ever be true? Or, with vulgar relativism, how could I live as if everything could be true or false all at once? Both would strand the learner of truth on the deserted island of the self. What folly, what reality irreverence, what selfish hubris lies in these extremes that touch one another.

At the same time, many good seeds sprout with “my-truth” or “one-truth” statements shared publicly and then take roots in community soils that blossom into more (“your why” is another bit of lingo). Such statements, made publicly, take true first steps, renewing our legs on lifelong journeys. But the crop rotator already knows that the content of such individual truth claims also take root unevenly after years of caring for “communities of interpretation,” as perhaps the last American idealist Josiah Royce calls both science and religion. One of my communities calls such (often locally tried, logically abductive) public statements testimony; another, hypotheses. The proving grounds of fruitful truths tilt away from solipsism and welcomes communities greater than the self and, as noted elsewhere, probably smaller than the so-called public; it dignifies but asks for more than solitary experience and lends extra credit to shared experiment. Living faithful for the good fruit of truth does not require propositional certitude; it requires cultivating living relationships across communities to their best available ends. As Emily Green Baluch wrote in her 1948 Nobel lecture, “those who are rooted in the depths that are eternal and unchangeable and who rely on unshakeable principles, face change full of courage, courage based on faith.”

Communities devoted to restoring truths together already acknowledge in their structure and operations that one person alone can neither confirm the unchanging status of a truth nor revise the status of truth for all others. Truth welcomes its utterance but it need not demand it. The voluntary public sharing of personal experiences, instructors giving invitations and assignments, second and third witnesses, independent verification, voting and public confirmations, committees and quorums, experiment and observation, expertise and authority, counsels and collegial review, and evidence—or, in short, how communities seek not their own power but to grow to serve and meet emerging truths—all these are just a few means for communities to cultivate truths, to paraphrase Royce's afterword, we grow from the one to the many, to the (potential) infinite.

How communities of interpretations work matters intensely. As the mother of modern management Mary Parker Follett reminded us over a century ago, “coercive power is the curse of the universe; coactive power, the enrichment and advancement of every soul.” Holding together such coactive powers and authorities that serve others, we make beloved communities that restore and cultivate truth and have much coactive work yet to do.

By contrast, all-or-nothing knowledge positions that claim to have power over others offer a fragile mortal caricature of immortal knowledge, misunderstood. Much modern abuse of science and religion follow the unscrupulous who claim authority as if power springs from science, omnipotence from omniscience. Nothing lasting, save distance and heartbreak, follows from coercion. What would non-coercive lasting growth look like? What would sustainably creative, coactive play look like?

Consider a perpetually sustainable game of baseball. As Steven Peck and James P. Carse allude differently, if the endless truth of baseball were nothing but more of the same repeated over endless innings, it would become a literal hell. To remain playful (and not a coercive curse), continuous play in a game would have to co-evolve where all players have a coactive role in the creative experiment, and play with and within the game's rules: since winning is meaningless, for example, why not experiment with the other team in conjuring a play grander than grand slams? Or bunting to steal home? Or a walk-off quadruple play? Or player trading mid-game? Would infinite games not prompt us to take joy in coactive play itself? Perhaps whatever teams compose our communities of interpretation—fields, parties, genders, companies—whoever cannot imagine creatively playing for, even becoming, the other team in creating a better game cannot yet claim to be playing for the eternities.

Truth games are not baseball games (or the harvest) but the analogy has not yet run aground or afoul: to be sustainable (or endless in theory), we play and evolve cooperatively. Fixed and relativist truths cannot be eternal for they cannot improve with disciplined bounds of creative coactive time, growth, and community. Inspired leaders tend to announce and update their followers with whatever they are prepared to receive, although global communities often measure change in seven-year seasons. (Consensus among scientists and coreligionists takes at least as long.) Poor is the harvest whose coworkers reverence the frail idols of snap judgment and overconfident caprice. Wrongly convinced that truth appears a fossil, an ancient and elusive deposit hidden in mountains of slag, fundamentalists and their mirror-image critics alike would often torch a whole field of claims before giving emergent truth the chance, the time, the community, and the coactive play it needs to bear fruit over the seasons and to become known for the good it does.

Much work lies ahead. Crop rotation remains an untested analogy. Yet, a fair subpopulation of at least my beloved communities—home, work, church, neighborhood—already live as if the following crop rotation article of faith were true: discerning eyes, beating hearts, and patient hands in the scrum of community cultivate more truth in a day than any true-false claim could contain in an aeon. As Ella Lyman Cabot once put it, “the art of living is becoming other people.” In a changing relationship, let oneself have the disciplined work over time, the sustaining community, and the release (cf. shmita) to change faithfully. In baseball and other infinite truth games, play with enough joy that one becomes part of the living game itself. In sustaining harvests, become the hungry, the community awaiting the harvest. One day, become the soil.

That which must be already is: what truth could be higher than that which works, that which proves sustainably practical? What analogy helps more than what already lives?

A Few Objections to Crop Rotation

Living our beliefs is, of course, not the same as rotating crops on farm fields. Crop rotation is an analogy, and analogies fail revealingly. Let's consider some objections.

First of all, why elaborate crop rotation as a metaphor at all? If the fruit of the metaphor of crop rotation is to cultivate more meaningful relationships with the world through patience, a commitment to experiment, and community inquiry, why bother with agricultural imagery at all except as an indirect means for organizing our ways in the world? What do we gain or lose by using crop rotation as a word for faithful living among living truths?

That question lands as the wager and experiment of this essay: no author who asks a question cannot answer it alone. It needs a chance to grow and cultivate truth among the lives of others. Outside of Kierkegaard’s essay “the Rotation of Crops” and the occasional riff about international diplomacy, I know of no other commentary on crop rotation as a metaphor for life, so the general use of the metaphor to stand in for these values has yet to be tested.

Thankfully, the metaphor of crop rotation invites other specific objections that we need not wait to consider. So let's dispatch with a few more obvious ones first, and then sit with a few more lasting limitations.

For example, our critic might assert that crop rotation, crudely understood, allows one to skip over inconvenient details. When do details matter, and if truth grows into the future, why bother with the past? Let’s say that I’m cramming for a big history test tomorrow. Might I, the lazy crop rotator, see no fruit in remembering whether, say, Columbus arrived in today’s Bahamas in 1492 or 1493 or 1491: why not rotate my study crops to claim that my best fruit would be to altogether avoid the headache and unpleasant evening of cramming? Might crop rotation excuse my waving away of details, along with libraries full of other pesky facts?

No, not at all. But first a moment of dignity: almost every reader knows the strain of cramming and the meaningless of memorizing facts without context the day before a test or presentation. That pain is real. But the generalization of the underlying complaint—that details don't matter if they don't matter to me—collapses the collective work of crop rotation into selfish convenience.

Skimping on learning misstitches time while working the fields: denying learning about others raises crops in the greenhouse shed of the selfish self. Imagine how well even the best recipes in life would turn out if our produce went no further than the potted plants on our one windowsill. Every feast, a flop! As Peter Stallybrass suggests, fine cooks get outside our own heads, improving our own recipes by sampling the best produce from the finest available farmer markets of ideas. Truth cultivation requires a long-term relationship to evidence and others who share the same commitments. To reread Kafka, “in the struggle between you and the world, back the world.” (Kafka’s final verb here is “sekondiere,” suggesting we hold the world’s coat in the duel against ourselves.)

Crop rotators should not dodge details like 1492 for several reasons: practical details motivate rotators who attend to fields wider than themselves. Whether Columbus arrived in the western hemisphere in 1491 or 1492 or 1493 or any other date, matters to the communities whose stories pivot around that detail, such as those indigenous people who lived and died through the first wave of colonizing Europe. The particular details of their stories matter to all those who care about the living histories of the ancient and current Americas. Doubt not that collective memory matters. We who seek a working picture of the world do well to extend fact-based empathy to the living and the dead alike.

Like all truths, Columbus’ arrival date marks a robust and living truth. It is neither fragile nor fixed. Wait, but it is fixed, you may object: how could it not be? It happened when it happened, you may object! Of course that is true. But given that serious historians know that we can never know the thing in itself and that timelines may wiggle with new evidence, we must remain open to the fact that if, in some hypothetical future, a consensus of professional historians faithful to the historical records were to discover that the conventional 1492 arrival dating was mistaken and that the correct dating were, say, either 1491 or 1493, then all that real, gritty labor of that future consensus truthmaking would revise and grow a new practical fact. That revised date would become true. History, like the proverbial partner in a changing relationship, would reorient itself with hard work and collective faithfulness to the best evidence at hand. That facts may wiggle endows the careful student of history with more, not less, value. Avoid cramming.

Truth is hard, truth is made. Communities faithful to facts and stories that matter make truth. Until that improbable Columbus hypothetical raises its head out of the soil of fact, we may all rest confident in the generations of professional historical effort that have built consensus around the 1492 detail and many others. In short, details matter to the communities that build and are affected by them. The word fact shares the same Latin root as factory: that which is made socially—not made up (invented) but made (constructed)—offers a firm foundation for reality. Try telling your local grocer or tax collector that your one dollar bill is worth a hundred and see what happens. Social construction often invites interpretation as flexible as jail cell bars! Truth is made, built, and revealed (three words for cultivation) through the forging of community consensus in fields of evidence and shared inquiry, not in the acrobatics of self-justification and self-aggrandizement.

Who cannot see in the hard work of cultivating fields of fruitful facts another name for restoring truths?

Here we can cut off our handy critic before they take another tempting leap: no, just because communities make truths by doing the hard work of cultivating them does not mean that a truth belongs to that community alone. Take a potent example: the enslavement of black Americans appeared to many US southern plantation owners before the Civil War as a convenient economy, perhaps even a conveniently “true” economy to some enslavers and their revisionist historians. Such a claim proclaims itself so offensively false because its fruits are demonstrable evil: slavery stands as the original sin of my nation. Lincoln explained at last in 1863 that the proposition “all men are created equal” hallowed the lives lost in the prior months. For centuries before and generations since, the living truths of black Americans had been ignored, abused, and enslaved; like ancient Israelites in the exodus from Egypt, the black American struggle has also best authored what freedom means today to my homeland. Many communities—like the descendants of once-enslaved black Americans and their listeners form—cultivate and restore truths that may serve the good of all people, not just the creator community. The promise of freedom restored by black Americans entails no less than that: a truth that, once dignified and cultivated by others, may serve, humble, liberate, and restore all people.

Meanwhile, the true fruits of enslavers, including their community-only claim, are obvious to all those who do not deny evidence: oppression, exploitation, and generations of subsequent structural disadvantages for their descendants. The claims that a community makes to justify its own truths may be tested by how well those claims work outside of that community. Crop rotators feel at home calling a thing what it is and enslavement evil.

Fair enough, our critic might pivot, but what about less obvious examples? How about impractical facts and details with less obvious stakes or consequences? Of course racism and 1492 matter but what about obscure details: what about, say, the textile weft and weave of the kepi hat found at the Union side of the 1861 Battle of Aquia Creek in the US Civil War. Surely such trivialities, whether appearing on a history test or the historical record, are not worth our common cultivation?

Many details do not matter. Thank goodness that is true most of the time! Still, like the processual truth of Santa, since we cannot yet know which questions will be asked of which details when, certain communities of crop rotators—such as historians and scientists, revelators and educators—have obligations to cultivate a future harvest of truth on all the best available evidence, and this includes getting facts right whose interpretation will become obvious in the future.

Take our kepi hat: a future observer may one day discover that, say, a particular wool weave in that Union soldier’s 1861 kepi hat comes from a particular manufacturer in the antebellum US South. Were that the case, a fresh flower of insight sprouts: an obvious point, the labor of enslaved Black Amerians would clothe both armies of a nation at war with itself; yet even more specific points may also surprise. Seemingly pointless details gain arrow-tipped points all the time. Just because a true detail does not yet have useful, reliable meaning does not mean it will not sprout buds, thorns, and roses in the future.

Like a detective ready to solve future mysteries, crop rotator communities may seek to welcome, gather, plant, and attend to the truth of all evidence, wherever or whenever it may be found, cultivated, and set aside to grow. Two cheers for record keeping, this essay by John Durham Peters echoes in a similar key. Professional historians and family-historical communities, although in different fields, may join arms in the shared task of restoring records over the centuries into enlivening truths.

The question here should be plain: how else might a cultivator of truth, stumbling upon an unexpected “useless” stray bit of fruit (a seed, a twig, a branch), find a use for it except, of course, again by planting, grafting, and keeping it in the fields and, maybe, one day seeing what fruit sprouts from its seeds?

Consider the good news that crop rotators—because they care for and cultivate the varieties of individual claims—also tend to welcome objections: in fact, crop rotators may develop, on the one hand, robust autoimmunity to nonsense as well as, on the other, a second sense for how to put a claim, no matter how nonsensical, to good use. (In other words, it is not the capacity to accept, block, or anticipate objections itself that makes rotation sustainable; rather it is the practice of adjusting to, learning from, and making better uses out of objections.) For example, a crop rotational read of, say, the flat earth community may not take literally their asymptotically improbable claims but, after rotating to see the fruit of flat earthers differently, we may take seriously their desire to land headlines as a community. On the surface of their claims, there’s little to stand on. But one would wait a long time for community members to come around to it: anachronistically resisting scientism with more scientistic Biblical literalism, or countering weak sauce with weak sauce, makes for a reliably bad bet. In fact it appears such an underwhelming look, the community appears to derive value from making bad bets on purpose and in public. Can we empathize with the instinct without entertaining nonsense?

As noted elsewhere, we may defuse conspiracy theorizing by modeling and inquiring about probable and improbable hypotheses: given a remarkably uniform physical universe, which appears more likely (and even more beautiful): a round planet like every other or a flat planet unlike every other? Since the community makes bad bets so they can feel special, they have little motivation to welcome the parsimonious claim that a physically uniform yet still profoundly diverse universe stands as the stronger witness to the specialness of creation. Still, for the rest of us, betting with the probable deflects outlandish claims like water rolls off a duck’s back. Setting aside the nonsense without reaction, the rotator also attends to and values the social story behind the community: conspiratorial claims lay bare the social exceptionalism—the bigger story—at stake behind every community’s self-identity as a possessor of special knowledge.

In either case the established crop rotator has time and thus finds no reason to rush to judgment, for they know healthy claims grow slowly and in the context of different soils within varying communities. Robust claims, like well-rooted plants, may bend with the winds without losing its grounding. Well-rounded worldviews, as it were, take shape over centuries of cultivating what works and slowly jettisoning what doesn't.

So if rooted flexibility applies to potent and impotent case studies alike, how well does crop rotation fare with the most obvious self-evident truths? It is, for example, a robust practical fact that 2+2=4, except for the mad protagonists in Dostoevsky, Orwell, and playful mathematicians for whom large values of two can sum to five (or six, depending on when one rounds). One could even postulate wild rounding rules like “round any value between m and n to 2,” rendering the sum of any two numbers four. Nothing about numbers or protagonists in literature prohibits such theoretical flexibility but the practical fact emerges that the only counting integer that can be added to two and then equal four is, if one wants a useful solution, another two.

2+2=4 holds true insofar as it does good work. The truths of plain mathematical statements like these lie not in some logical a priori, not in some proverbial more true soil beneath the soil. If there were one ur-turtle of truth (let’s name her a “truthtle”?) beneath all other turtles, as Dr. Seuss anticipated, it would be the first to protest its ridiculous position. (I suspect the ur-truthtle would eagerly give up their position to hold the world’s coat!) The truth of mathematics often lies in how most people use it most of the time; its fruits are practical. Among professional mathematicians, even though their formalisms may not be clear to many outside (or even inside!) the specialist community, mathematics still offers a practical language in which communities can hash out consensus. How does one arrive at consensus? Math teachers model this basic truth about problem-solving by which one arrives at their answer. The answer to the problem, whether correct or not, contains less truth than the solution, whether correct or not: the difference? The process of solving by careful and creative reasoning and showing one’s disciplined work (equation signs forming a column, on grid paper, each step clarified with equal signs aligned, etc.) sums to more in the long-run than the truthiness of any answer alone. Arithmetic truth arrives after the fact. Thus the lesson of crop rotation too: truth is made in solutions, not in possessing answers. Show your work and share.

Permit the following flight of imagination. Suppose there exists an intelligent alien species whose anatomy is unlike our solid bodies. Imagine that, say, this highly intelligent species of vaporous beings inhabit the thick atmospheres enveloping gaseous exoplanets: with no fingers and no eyes, they move through clouds like we wayfare across cornfield paths. Perhaps they sense and transverse their environments through forms of harmonic wavelengths, gaseous vector fields, and Brownian stochastic processes. Perhaps their offspring would learn to “count” not 1, 2, 3 but by different Lévy processes? These diversely yet still divinely embodied aliens would have little use for our mathematical basics: counting fingers, countable integers, distinct objects, object permanence, discrete digitality, etc. If our species shared no senses, under what conditions would we share sensemaking? As reasoning beings, they might be expected to develop their own kind of formal processes, mathematics, and truths: instead of counting on their fingers, these aliens might have chalkboards and canvases among the clouds, comet trails, and intergalactic gasses.

Either way, the truth of such alien mathematics does not hang on by its correspondence or contradiction with ours. If their alien harmonic arithmetic works after the fact in their gaseous environments, just as our mathematics does on our planet, so much the better! The question then becomes how much joy and truth, struggle and goodness could an interspecies congress of mathematicians create in experimenting together across our respective forms of reasoning? Can we even imagine the herculean task of translation? Perhaps new homeomorphisms and revealing disjunctures between formal systems would emerge? How much truth might be found in our learning of alien arithmetic? Consider the hypothetical wonders yet to be uncovered in the atmospheres of exoplanets! What atmospheric advancements and challenges might follow?

How much more, then, should such a joyful attitude of collaborative truthmaking apply to all truth-restoring communities less alien than such exoplanet atmospheric algebras? As our joy scales back down to earth, the opportunity for truthmaking and its translation becomes more, not less, radiant—more, not less, practical: while we should welcome all communities to the table of truthmaking, only the fool ignores that different communities have different specialities. Would not even the haplessly postmodern among us not ask, say, dentists about teeth, plumbers about plumbing, social scientists about society, and mathematicians about mathematics? Modernity appears an ongoing lesson in validating and then trusting expert communities to cultivate truths for others so long as others also participate in what and how those truths work on them. The vaccinations data in the COVID-19 pandemic trace such bitter yields. Modern people, like all people of faith, live by learning how to trust truths about reality that the eye cannot see. The alien algebras and the statistical models of epidemiologists may be distant cousins in the art of understanding air-borne miracles and mysteries: the test sounds the same, who would not take joy in recognizing invisible truths that still bear life-saving fruit?

So just because a claim provides convenient use to a community (especially a claim that denies another community its expertise) does not yet mean that claim or practice holds true; by the same token, as that claim or practice serves a growing number of communities, nothing could become truer than a claim whose good use lifts and saves.

Good use often makes truth sweeter and more hardy (not totally fixed nor totally flexible) than proof by priors. Take Bertrand Russell and Alfred Whitehead, who almost went mad failing to reduce arithmetic truths to its formal logic priors over the 2000 pages of their little read but still influential Principia Mathematica. After this revealing deadend, both authors pivoted into becoming leading processual crop rotators by other names. Most people can agree, breathe, and find no cause for denial, logicism, or fanaticism in the practical claims that two plus two is four. Like arithmetic, reality is robust.

It works, if unevenly.

So let’s cultivate better uses for it.

Crop rotation lifts, not lowers, the bar for truth. As Peters develops, the marvelous clouds bring into view the low-level heavens above and the ground beneath (the word “cloud” is related to the word “clod” as in a clod of earth). Crop rotation also elongates, not rushes, our approach to clearing that bar in advancing a loving community’s cultivation of truth. All evidence matters and communities have time, including those that develop tool sets for nurturing, caring for, and also passing judgment about the content of claims.

Wait, our diehard objector may continue, does not such a perpetual postponement of the final truth mean that all things could be true or false in the future? No. It is because truth takes time that such extremes cannot come to be, or rather even if in some distant universe where all things could become true or false, it would mean nothing here and now. Just because, as Jean-Yves Lacoste wrote, “meaning comes at the end,” does not mean we are not experiencing it continuously. Truth relativism implies one opposite of crop rotation’s faith in weighed, unhurried evaluation. After walking the fields, a few things are self-evident: truth arrives after the fact, facts are already all about us, and reality breathes robustly and lies ready for cultivation.

What is to be done? Dig in here and now, confident that crop rotators, through learning and community service, develop gifts of discernment in evaluating and setting aside claims that are wrong in content and negative in effect. No matter what the future holds, the practical fact holds that, in the Borgesian library of the conceivable, most claims are nonsense, senseless, or not useful.

If I were to use my claims about the truthfulness or falseness of any tradition, including my own faith and profession, to badger and belittle others, then the first fruit of my action would be to anger, bruise the hearts of, and give headaches to others. There ensues no difference in effect whether my good intention was to share my immediate internal truth or my expression of eternal, external truth (naive identitarian and dogmatic claims both wobble about the my in “my truth”). Regardless, I have, in the blemished fruit of my callous attacks, rendered the truth I possess, whatever its original value, sour and unsustainable by my preparation and presentation of it to others. To the parable of the sower, we may echo the parable of the caring and negligent gardener. How many worthwhile truths have shriveled in cruel hearts and manipulative hands? Who would deny that trolling and bullying poison real relationships that might otherwise bear and cultivate truth? Who feels no sting: how much truth have my words lost to the world?

Between seeking brutal honesty and unpleasant truth, on the one hand, and comforting lies and slippery persuasion, on the other, lies a trap. This is not the choice. Instead, the prudential crop rotator steps aside to model hard truths with dignity and lays aside untruths with charity.

Kindness, care, and humility are necessary interfaces for developing stronger communities capable of the full fruits of robust self-correction, discernment, ripened judgment, and truth cultivation. Loving communities evolve generous models of faithful correction and living in tension among those unlike oneself. Some of the best classrooms, church meetings, laboratories, and conversations are diverse, especially when folks often don't see the many differences that bind them together. Vibrant learning cultures require kindness and seeking understanding, although cultures of eggshell diplomacy and default niceness sustain neither kindness nor understanding. Exclusive niceness stands out as a corruption of necessary kindness.

Here master teachers model rotate the crops differently in their public teaching: Socrates asked probing questions in dialogue to reveal contradictions. By contrast, when faced by a truth culture resting on the Pharisees’ worship of fragile contradiction, Jesus reproved at times and spoke in parables that demanded no dialogue with others. Immersed in a fragile public culture impoverished by the gotchas of cheap contradictions, the master teacher deflects, separates, (as James Egan develops here) jokes, sobers, pauses, matures, and slows the public scrum of competing claims. He lived and modeled enduring truths routinely without words and sometimes with words. At other times, he corrects with clarity. The moment the disciples’ harmony settles into a static unanimity of doctrine, master teachers introduce dogmatism-deflating probes, questions, and differences, whether cantankerous dialectics or open parables.

Crop rotators prune when the soil and the weather call for it.

Perhaps a life art of cultivating truth consists of nothing other than growing and putting truth to better use. During a faithful life among living truths, crop rotation looks away from possessing and storing an orthodoxy of doctrines. It would attend to the art of living a robust orthopraxy worthy of truths borne by many. Truth has weight. In bearing and building truth together we literally bear one another's burdens.

The content of our beliefs—first principles and truth claims—profoundly does matter but not because it functions as a polished antique perched precariously on a shelf. Belief content matters because it waters the roots of belonging that form communities around those claims. Formed around these claims, communities then use those claims to develop good works worthy of sustainable harvests. Claims that hurt many and serve few may and should be set aside: crop rotation has no use for metaphysical mysteries, infinite regresses, and semantic quandaries. Menacing metaphysical ledges of the psyche fade as we glance down at the rich soil below our feet. Crop rotation welcomes data-informed (but not blindly data-driven) experimentation, evidence-rich interpretation, attention to communal consequences, and seasonal cultivation of care, community, and truth. Private and public dogmatisms are, alas, easier and cheaper to entertain than community truthmaking. Raw data, Lisa Gitelman catches Geoffrey Bowker saying, is an oxymoron; evidence and data arrive both dirty and precooked, demanding that professional communities reflect and carefully interpret it. Evidence should be neither simple nor optional: truthmaking demands communities of expertise, care, attention, and criticism.

But the bankruptcy of bad ideas and the need for patient hard work pose no serious obstacle to practical people after truth. There’s still much to do in pivoting between fields, cultivating the best available claims, taking rests and breaks from truth caring, seeking to feed themselves and others the riches of the harvest, and giving away surplus charitably. Whatever the challenges, the standard of truth remains: if there were something more practical and true than available in a mere metaphor like a crop rotating faith, who in it would not faithfully welcome and encourage belief in just that? What else could crop rotation be but faithfully seeking its improvement?

PART THREE

Benjamin Peters is a Wayfare Associate Editor. He is also a media scholar, author, and editor interested in Soviet century causes and consequences of the Information Age.

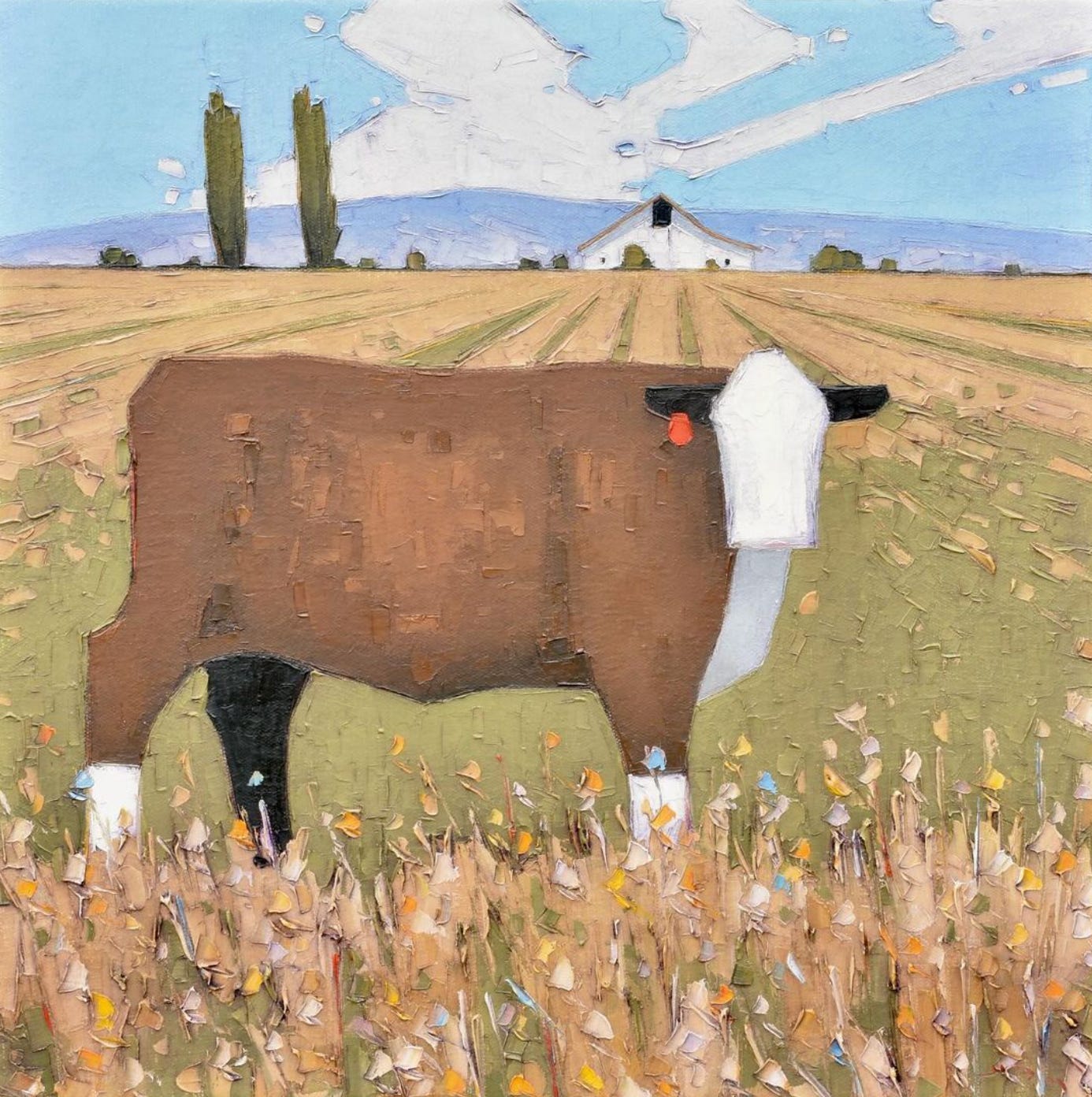

Artwork by Jeffrey R Pugh.