In the mid-nineteenth century in rural West Virginia, a woman named Ann Reeves Jarvis bore at least eleven children over the course of seventeen years. Only four would survive to adulthood; the rest would die of measles, typhoid fever, and diphtheria, all common epidemics in Appalachian communities at that time.

In 1858, at the age of 26 and while pregnant with her sixth child, Ann organized “Mothers’ Day Work Clubs” to do something about these dire circumstances. Club members made home visits educating other mothers on how to improve sanitation, explaining the importance of boiling water and demonstrating how to keep food from spoiling. They raised funds to buy medicine and supplies for impoverished families, and hired women to provide assistance in homes where the mother was suffering from tuberculosis or other health problems. They developed programs to inspect milk long before there were state requirements to do so, and when necessary, Club organizers even quarantined entire households to prevent the spread of disease.

When the American Civil War erupted, Ann urged her Mothers' Day Work Clubs to provide relief to both Union and Confederate soldiers. When diseases broke out in the military camps, Ann and her club members nursed suffering soldiers on both sides, treating the wounded and teaching sanitation and disinfection.

After the war, both Union and Confederate soldiers returned home to West Virginia. In 1868, Ann and other women of the Mother’s Day Work Club planned a "Mothers’ Friendship Day" picnic, at which former Union and Confederate soldiers and their families gathered to sing and share a meal together. Despite initial fears and threats of violence, the event successfully began a process of community healing and reconciliation, and Mothers' Friendship Day became an annual event for several years.

As a woman with children, raised in a religious community that highly values women having children (at times, it can feel, at the expense of all else,) and in a society that somehow prizes having children (but not too many) while simultaneously failing to support us in the work of actually raising those children, I’m intimately familiar with only a few of the ways our modern observance of Mother’s Day can bring up complicated feelings.

I have chosen to have children and to spend significant portions of my day-to-day life engaged in the work of caring for them; I’m currently pregnant with my third, with two other young children at home most of the day. I find this work fulfilling and enlivening and exhausting and mundane, and not the only thing I want to do or be known for or praised for. I enjoy and find nourishment in other work I do that has absolutely nothing to do with caregiving or children. I have close friends who deal with infertility, and others who have chosen never to have children and feel absolutely no sorrow or regret about that. All of us struggle in different ways to live as women in a society that expects us to have children and yet devalues the work of caring for them. I believe the stories and the work of women who birth and care for children are immensely valuable and important, and at the same time, I’m deeply wary of the danger of venerating that work as the single most valuable thing any woman can produce.

Though the meaning and observance has changed significantly over the decades, I can’t help but wonder—what might a Mother’s Day more in line with the mission of its earliest advocates look like? What does this history have to offer us as we seek to honor mothers and motherhood in ways that offer healing, not harm?

In 1870, at the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, Ann Jarvis’ abolitionist colleague Julia Ward Howe (the poetess behind "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," now in her early fifties) drafted a manifesto of peace, traveling to Europe to deliver it at an international peace conference. When she was prevented from speaking at the conference because she was a woman, she rented her own theater in London to deliver her “Appeal to womanhood throughout the world,” which came to be known as her Mothers’ Day Proclamation:

“Again, in the sight of the Christian world, have the skill and power of two great nations exhausted themselves in mutual murder. Again have the sacred questions of international justice been committed to the fatal mediation of military weapons. In this day of progress, in this century of light, the ambition of rulers has been allowed to barter the dear interests of domestic life for the bloody exchanges of the battle field. Thus men have done. Thus men will do. But women need no longer be made a party to proceedings which fill the globe with grief and horror. Despite the assumptions of physical force, the mother has a sacred and commanding word to say to the sons who owe their life to her suffering. That word should now be heard, and answered to as never before.

Arise, then, Christian women of this day! Arise, all women who have hearts, Whether your baptism be that of water or of tears! Say firmly: We will not have great questions decided by irrelevant agencies. Our husbands shall not come to us, reeking with carnage, for caresses and applause. Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy and patience. We, women of one country, will be too tender of those of another country, to allow our sons to be trained to injure theirs. From the bosom of the devastated earth a voice goes up with our own. It says: Disarm, disarm! The sword of murder is not the balance of justice. Blood does not wipe out dishonor, nor violence vindicate possession. As men have often forsaken the plough and the anvil at the summons of war, let women now leave all that may be left of home for a great and earnest day of council.

Let them meet first, as women, to bewail and commemorate the dead. Let them then solemnly take counsel with each other as to the means whereby the great human family can live in peace, man as the brother of man, each bearing after his own kind the sacred impress, not of Caesar, but of God.

In the name of womanhood and of humanity, I earnestly ask that a general congress of women, without limit of nationality, may be appointed and held at some place deemed most convenient, and at the earliest period consistent with its objects, to promote the alliance of the different nationalities, the amicable settlement of international questions, the great and general interests of peace.”

“Peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you,” (ERV: “I give you peace in a different way than the world does,” NLV: “I do not give peace to you as the world gives,”) says Jesus of Nazareth in the Gospel of John, chapter 14 verse 27.

One of the most consistent and intriguing messages I find in the life of Jesus as portrayed in the New Testament is that power does not look the way “the world” expects it to look.

Many might have expected a Messiah similar to Caesar Augustus—a ruler who was also known as the “Prince of Peace,” but whose proffered peace came through military might and the violent elimination of enemies. Instead, the gospel authors describe a baby born into poverty, who lived and taught in relative obscurity, and who then rode a donkey (rather than a war horse) into Jerusalem, where he was summarily executed by the political powers of his day. Somehow, the gospel authors insist, this is who will bring us lasting peace. Somehow they ask us to believe what seems frankly impossible by the world’s standards of power.

The kingdom of heaven is like a woman baking bread, Jesus says. It’s like a man planting a seed. It’s like ordinary, mundane, domestic life. It’s found in all the hidden places the world never bothered to look.

Perhaps this is also one of the messages of these early Mother’s Day efforts—that power does not look like we’ve been taught it must look. A meaningful contribution to the betterment of humanity is not and never could be limited to people of just one gender or family composition, and never could be captured in what the world chooses to honor and recognize.

What if Mother’s Day was about women being encouraged, supported, and heard in their peacemaking efforts, whether those take place in the political sphere, the domestic sphere, or both?

What if we recognized that people who do care work have something important to offer the political sphere, not in spite of but precisely because of their experiences with care work?

What if tenderness is power, and what would our world look like if it was recognized as such in more than just women and mothers?

Despite being denied the opportunity to speak at the peace conference because of her gender, Julia Ward Howe had her proclamation translated into several different languages and spent the next two years distributing it and speaking to female leaders in Europe and the US, advocating for a Mothers’ Peace Day.

On June 2, 1872, Julia successfully held the first Mother’s Day for Peace in New York City. Cities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago would hold annual Mother’s Day services centered on pacifism every June 2nd for the next several years, but by the time the US entered the Spanish-American War in 1898, these events had faded out almost entirely.

Ann Reeves Jarvis, meanwhile, never stopped advocating to honor and support the work of mothers in her community. When in her 70s her health began to fail, her daughter Anna Jarvis stepped in to care for her until her death in 1905.

Familiar with both her mother’s work and the work of Julia Ward Howe, Anna embarked on her own campaign to establish a National Mother’s Day. Motivated by a deep love and admiration for her mother and a conviction that the work she had done mattered and deserved recognition, Anna’s first Mother's Day celebration was successfully held in West Virginia in 1907, in the church where her mother had taught Sunday School. From there the custom spread, and in 1914 President Woodrow Wilson declared the first national Mother's Day.

These efforts make me wonder, how many people in my own life are quietly and insistently going about the essential, quotidian work of caring and peacemaking, with very little praise or recognition? In the gospel narratives, particularly in Luke, Jesus pays special attention to those whom society would often overlook and ignore. Perhaps Mother’s Day can be an invitation to consider who today is being overlooked by society, and how we can elevate and honor them and their contributions.

Dorothy Day is rumored to have quipped that everyone wants a revolution, but no one wants to do the dishes. What if Mother’s Day could serve as a reminder to honor those who “do the dishes” by doing the often-unseen, mundane, immensely valuable work of organizing, caring for others, picking up the trash, providing food (as Jesus so often did), and more? Perhaps this day could remind us of the importance of what is often called “domestic labor”—and that its value does not go up or down based on the gender of the person performing it. Scripture records that God loves us as a mother (as a hen gathering her chicks, and as a bear defending her cubs), and I believe a Mother God demonstrates the divine potential for all of us in what has traditionally been linked only to the feminine.

Mormon historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich famously wrote that “well-behaved women seldom make history.” Perhaps Mother’s Day can remind us that we don’t have to make history to make a difference, and to look beyond the history-makers for those who deserve our respect and honor. As Mary Ann Evans (better known by her pen name George Eliot) reminds us in the concluding words of Middlemarch, “…the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

One of the most meaningful and powerful spiritual experiences in my life these days is participating in a non-auditioned community choir called “The Family Folk Machine.” Led by a soft-spoken, petite middle-aged woman who commands respect from behind an acoustic guitar, people in my community ranging from my own toddler to folks in their late 80s gather weekly to sing and write songs insisting that love is real, that peace is coming, and that there are in fact people willing to work alongside you to create a better world, small act by small act.

In times of immense political upheaval and dissent, when neighbors feel increasingly distant from neighbors, and wars and rumors of war dominate headlines, does it feel pointless to gather and sing our silly little folk songs? At times, yes. And yet far more often, I feel that this is precisely the work I should be doing. Bringing my children to meet people in their community they otherwise would never cross paths with, to learn to love and be loved by people very different from us, feels vitally important. Joining together in songs that remind us and those who come to hear us of our deepest values has become for me an essential and deeply spiritual practice I hope never to give up. Coincidentally, our spring concert this year takes place on Mother’s Day.

This Mother’s Day, perhaps we all could learn to place more value on the quiet, mundane work of caring for each other and waging peace. Maybe this is what power looks like, too.

As we seek to better honor the founders of Mother’s Day, however you choose to celebrate (or not!), may we remember never to let gender limit who we see as capable of important work. May we see the work of care and peacemaking as valuable and important, whoever it is done by. May we elevate and honor those our society forgets and ignores. May we be inspired to recommit ourselves to tangible acts of peacemaking and care, however we can and whatever our sphere of influence.

Cecelia Proffit lives in Iowa City with her family.

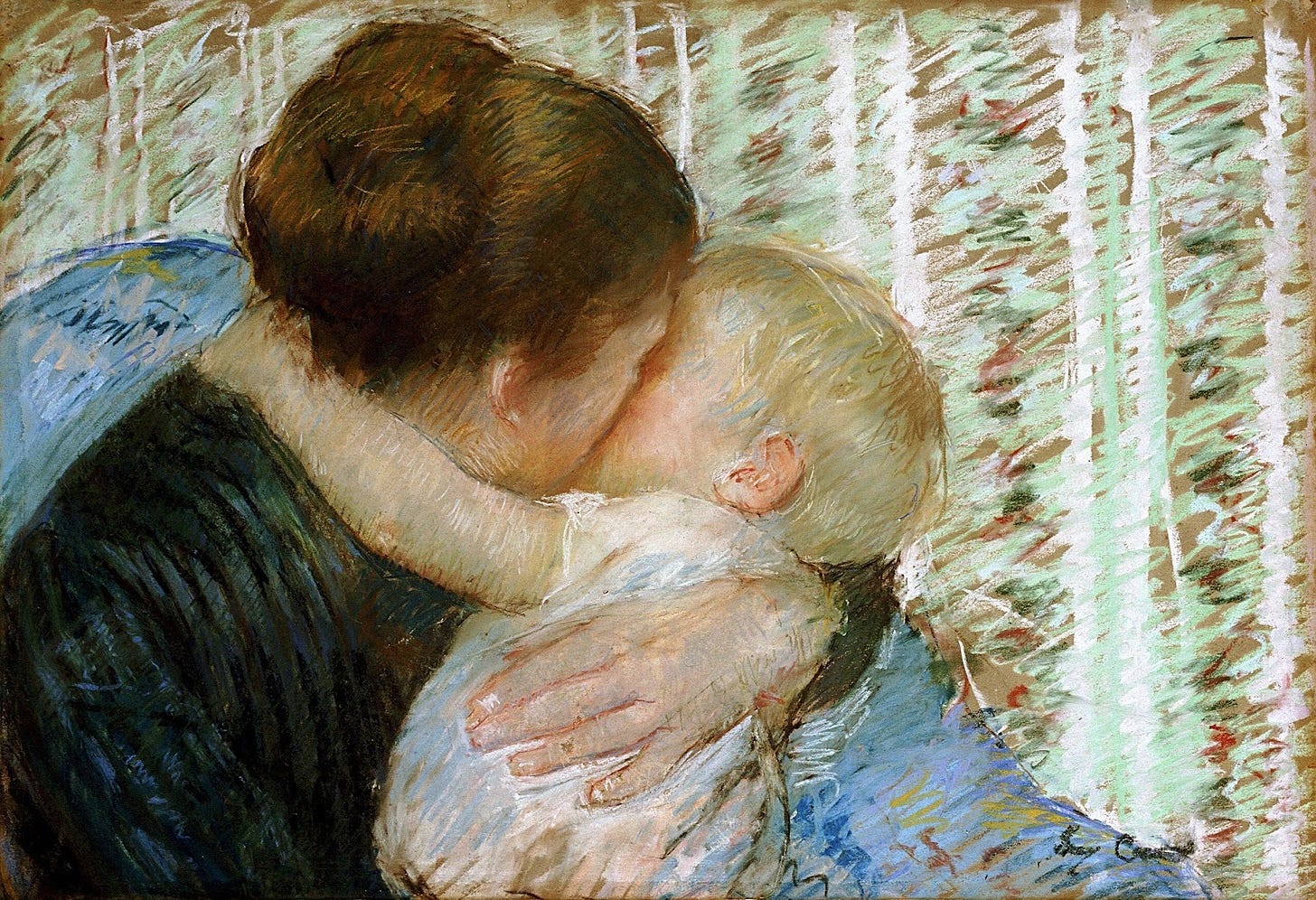

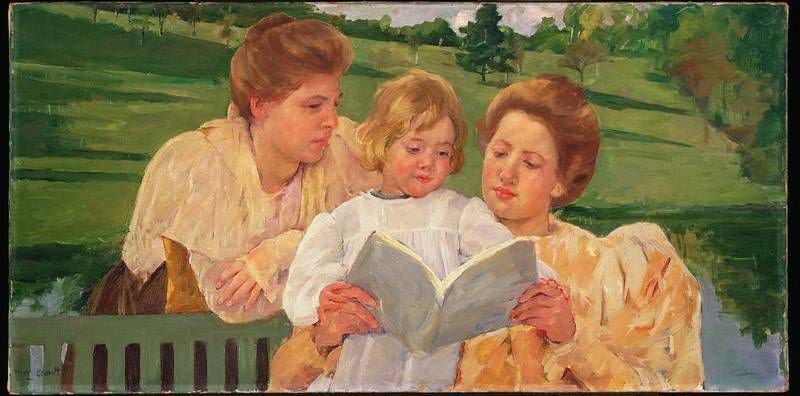

Artwork by Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot.

Overflowing with Family

Do you have a family? The question came over the phone from the stake family history coordinator. I had signed up to be a FamilySearch indexer, and she called to welcome me to the team and get to know me. Though “family” is a capacious category, I knew she was really asking two very narrow, specific questions:

Hymn of the Alloparent

I recently learned that my two-year-old son calls his nursery leaders “Mama” and “Dada.” My son is not one of those toddlers who colors quietly during church. Instead, on this particular Sabbath, he had decided to be an especially noisy allosaurus during the sacrament, so I took him out into the foyer. I held…

An Expanse of Light & Memory

I can’t remember the first year of my daughter’s life. I think, write, say those words and my chest tightens, grief and shame washing through my body. I can’t remember. I can’t remember. The hazy recesses of memory recall an urgent call to Heavenly Mother around this time. Maybe my spirit subconsciously knew to prepare for impending darkness, or perhaps …

I love this with my whole heart. Thank you for your beautiful research, nurturing work, and advocacy, Cece