Hymn of the Alloparent

I recently learned that my two-year-old son calls his nursery leaders “Mama” and “Dada.” My son is not one of those toddlers who colors quietly during church. Instead, on this particular Sabbath, he had decided to be an especially noisy allosaurus during the sacrament, so I took him out into the foyer. I held him in my arms as he squirmed and wiggled and whined, trying to get free so that he could burst back into the chapel. At that moment, his nursery leaders walked in the door. My son saw them and immediately cried out, “Mama, help! Dada, help!”

In hindsight, viewed from a distance, it was a humorous exchange. But in the midst of the experience, all I felt was guilt. Like my son’s call for help meant that I wasn’t living up to the heavy responsibilities of motherhood. All of my inadequacies as a parent flashed through my brain in rapid succession: all the times I felt annoyed at my children’s unending requests, or I didn’t sit on the floor to play or read with them. The times when I raised my voice or made empty threats because it was easier than connecting with them in a difficult moment. The times I lost my patience or my temper. As my son reached out to his dear nursery leaders, all I could think was, Am I so insufficient as his mother that someone else could so easily take my place?

Of course, this kind of “mom guilt” is not unique; parents all over the world worry about doing what is best for their children. But I feel as if I also had another layer of guilt, this one connected to my religious upbringing. Being raised in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I had heard so many talks and lessons about the importance of the nuclear family, and motherhood in particular. “None other can adequately take her place.” And now here was my child, calling out for another woman to be his mother. Of course, I also understood that these depths of meaning cannot be attributed to a toddler whose current method of communication is mainly growling like a dinosaur, so I tucked away my discomfort and sent my son to nursery. A few days later, still a little raw from that experience, I discovered the idea of an “alloparent,” and I understood that what had felt like my son replacing me as a parent was actually him finding support in ways that both nature and God intended. In that moment of frustration, an alloparent was exactly what my little allosaurus needed.

An alloparent is someone in a community who helps raise a child that is not their direct offspring. Some examples of alloparents can include church leaders, grandparents, stepparents, neighbors, aunts, uncles, schoolteachers, cousins, family friends, even siblings or stepsiblings. I was introduced to the term in the book Hunt, Gather, Parent by Michaeleen Doucleff. The book is a collection of parenting lessons that Doucleff gathered as she visited with traditional cultures all over the world—specifically, the centuries-old child-rearing methods of the Maya people, the Inuit people, and the hunter-gatherer societies that still exist today. I sought additional information about the anthropological understanding of alloparents in the book Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding by anthropologist Sarah Hrdy. Both Doucleff and Hrdy explore alloparenting mainly in the context of hunter-gatherer communities. But as I read these two books and learned more about alloparenting, it all felt comfortable, even familiar to me. I realized that, while alloparenting may not be a strong norm in Western society as a whole, alloparents are actually very important in the doctrine and culture of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

With hymns like “Families Can Be Together Forever” and “Love at Home,” lessons for children and youth celebrating temple marriage, and countless conference talks about the weighty responsibilities of mothers and fathers, it sometimes feels as if a majority of the Church’s teachings revolve around the importance of the traditional nuclear family unit. But, while the nuclear family is absolutely important to both the Church and our society today, most scholars characterize the exclusive focus on the nuclear family as a shift that only occurred within the last century. Prior to the nuclear family template, human society established and defined families in a slightly different way. Vestiges of this societal organization can be seen in the structure and traditions of ancient and contemporary tribal communities. For example, in the Nayaka hunter-gatherer tribes in southern India, “adults call all the children around their home ‘son’ or ‘daughter’ . . . and all the older people in their community ‘little father,’ . . . and ‘little mother.’” Church members might recognize this tradition as similar to one of our own: calling each other “brother” and “sister.”

We are blessed in our faith tradition to have an understanding of families that spreads so much farther and goes so much deeper than just the nuclear family unit. We believe in a family that can be sealed together for eternity, through countless generations, from child to parent to grandparent. It’s a family unit that is just as important and serves just as many purposes as the modern nuclear family. The branches of this eternal family tree spread wide enough to encompass siblings and cousins and aunts and uncles. Even when loved ones have passed from this life, we have the power to graft them onto our living tree through posthumous temple work. And, if you dig down far enough, you’d find that we all spring from the same roots. You. Me. Your neighbor. A stranger on the other side of the planet. Across distance and time, we share both the same heavenly parents and the same physical ancestors. We call each other “brother” and “sister” for good reason.

This Latter-day Saint tradition holds multiple levels of doctrinal meaning for us; it comes from our knowledge about the family and our unique beliefs about God’s sealing power. It also speaks to the existence of a religious family, one into which we are “adopted” when we take upon ourselves baptismal covenants and agree to bear one another’s burdens. But while our tradition of calling each other “brother” and “sister” was born of ancient knowledge that was restored through modern revelation, the Nayaka practice comes from ancient knowledge that was never lost. They call each other family because they treat each other as family. Every child is provided for and cared for by every adult. Every elder provides wisdom and nurturing to those who need it. The group works together to raise strong, healthy children who share their societal values.

In the social sciences, it has been theorized that this kind of alloparenting was necessary for the success of the human race. Human children are born so much more helpless than other species and stay helpless for so much longer than any other species. In ancient hunter-gatherer societies, it would have been prohibitively challenging for a mother and father alone to provide all of the attention, protection, and calories that a baby needed to survive. Alloparents would have vastly improved the chances of keeping children alive in an unforgiving, prehistoric setting. Today, parents rely on complex economic systems to provide for their children materially. Feeding a child involves supply chains that stretch around the world, sustained by too many workers for us to ever meet and thank. But our economic systems are not as effective at providing emotional relationships, and research suggests children do better developmentally when alloparents are directly involved in their care. One study found that, in a Gusii village in Kenya, “even though a Gusii child’s nutritional status was best predicted by the security of his attachment to his mother . . . the strongest predictor of empathy, dominance, independence, and achievement orientation often turned out to be a strong attachment to a nonparental caretaker.” And a series of studies conducted in Israel and the Netherlands found that “overall, children seemed to do best [socioemotionally] when they have three secure relationships—that is, three relationships that send the clear message, ‘you will be cared for no matter what.’”

Within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, so much time and so many resources are dedicated to teaching and raising other people’s children. In fact, in 2019, some of the bishop’s responsibilities were shifted to the Relief Society president and elders quorum president because, in President Russell M. Nelson’s words, the bishop’s “first and foremost responsibility is to care for the young men and young women of his ward.” The alloparenting done within the walls of a meetinghouse can have resounding benefits for the children, families, and alloparents involved. As newlyweds living in Northern Virginia, my husband and I served as Sunbeam teachers. For two hours every Sunday, we had the opportunity to teach those little boys valuable lessons, like “Jesus loves you” and “You are the boss of your own body (We don’t kiss our friends at church).” We taught them Primary songs, fed them Goldfish and mini marshmallows, and reminded them to flush and wash their hands after they used the bathroom. And all week long, we loved them. They weren’t our children, but they were “our kids,” and our involvement with them expanded our hearts and enriched our lives. The experiences that we had serving as alloparents to those Sunbeams would even help us as we started parenting our own children. Years later, when I learned that my five-year-old son had been sent to the principal’s office for chasing down his friends at recess to give them kisses, I could have panicked. Where did he learn this? This can’t be normal. Do we need a child psychologist? But thanks to my experiences with those three-year-old boys, I not only had a lens of “normal childhood behavior” with which to compare my son, but I already had a “we don’t kiss our friends” speech ready to go.

Of course, that’s not to say that one needs a calling to participate in alloparenting. Primary General President Sister Dwan J. Young taught, “We are all teachers of children—parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents, priesthood leaders, ward members, neighbors. Children are always watching and learning. We teach them through our behavior as well as by what we say. They watch how we treat each other. They listen to the voices of their parents and to the voices at church.” As a ward organist, I take the sacrament on the stand every other week, leaving my husband to corral our four children in the pews. On one such week, I heard the shriek of my allosaurus/toddler as my husband carried him out of the chapel, leaving our three older kids sitting on their own. The fighting began just as soon as the sacrament prayer ended. I felt my jaw clench as my daughters’ bickering disturbed the quiet reverence of the chapel. I started to calculate which would be a greater interruption to the meeting: me rushing down from the stand in the middle of the sacrament, or the imminent name-calling and subsequent tears. But before I could land on a decision, my neighbor and friend (who also happens to know my children as one of their elementary school teachers) quietly shifted to their pew. She held my youngest daughter on her lap and whispered kindly in her ear. My life is peppered with tender moments like this, in and out of my church experience. My brother rocking my newborn baby to sleep. The next-door neighbor inviting my kids over for homemade ice cream. A second-grade teacher wiping frustrated tears from my son’s cheeks. I never feel so loved as when I see others loving my children.

Studies have shown that alloparenting benefits children, nuclear families, and even the alloparents themselves, but perhaps the greatest benefit of alloparenting can be seen in human society. When a mother hands her child over to a teacher, grandparent, cousin, neighbor, sibling, or babysitter, she is manifesting a society built on trust. Evolutionarily speaking, she has to be reasonably confident that the person holding her baby will care for them, feed them, and protect them from danger. She has to believe that human society is dependable and that the world is well intentioned. By extending this kind of trust to the world around her, a mother creates a large family system for her child, which the child, in turn, learns to trust. It’s a difficult ask for me—I’m the kind of mom who likes to feel “in control.” Letting my children develop healthy relationships with other adults means giving up some of that control. It means letting my kids learn that “different” isn’t necessarily “wrong.” And alloparents must do their part to create a system built on trust, as well. When acting as an alloparent, we need to be trustworthy—develop relationships with the parents of the children we care for; participate in and abide by the rules outlined in youth protection trainings; support those who come forward as victims of abuse. These kinds of measures can not only protect children and families from harm, but can also protect the sacred trust required to sustain an alloparenting society.

However, this trust can also be fragile, and today’s Western culture seems to be pushing society in the opposite direction, engendering distrust in the world by separating us from each other. In Hrdy’s words, “The modern emphasis on individualism and personal independence along with consumption-oriented economies, compartmentalized living arrangements in high rise apartments or suburban homes, and neolocal residence patterns combine to undermine social connectedness.” As this feeling of disconnect increases, as we turn inwards to focus on our nuclear families while excluding a potential social network of alloparents, we teach our children that the world cannot be trusted. And, perhaps more significantly, “a subset of children today [will] grow up and survive to adulthood without ever forging trusting relationships with caring adults, and their childhood experiences are likely to be predictive of how they in turn will take care of others.” Children who do not know how to trust the world will grow and raise their own children in that same distrustful environment. Indeed, as the Family Proclamation declares, the eternal family is “the fundamental unit of society.” And as generations of humans forget how to trust and care for their eternal spirit brothers and sisters, society will crumble as “compassion and the quest for emotional connection . . . fade away.”

We are accustomed to thinking of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as the home of the restored gospel; nearly every fast and testimony meeting, someone stands up and expresses their gratitude for and faith in the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. But it is important to remember, in this world of increasing division and individualism, that the Church is also the home of the restored family—an ancient, eternal, all-encompassing family, where the needs of a single child are met by a village of loving alloparents. The practice of alloparenting is even modeled by our Heavenly Father, as President Gordon B. Hinckley reminds us. “Never forget,” he said, “that these little ones are the sons and daughters of God and that yours is a custodial relationship to them, that He was a parent before you were parents and that He has not relinquished His parental rights or interest in these His little ones.” Following our Heavenly Father’s example in this situation requires sometimes stepping back as a parent—not relinquishing our parental rights and obligations, but allowing our children to make healthy, loving connections with their nursery leaders, aunts and uncles, or friends’ parents. It means building trusting relationships with your neighborhood librarian, your child’s schoolteacher, or your elderly neighbor. It means understanding that your child and your family might need something that it can’t manufacture from within. And it means functioning as an alloparent to children outside of your nuclear family unit, as well. In the wise words of Subion, a Hadzabe mother in Tanzania, “Ultimately, you are responsible for your own children, but you have to love all the children like your own.” I’ll admit that sometimes it’s difficult as a parent to step back and watch the young, newlywed Primary teachers fumble as they try their best to teach my children. And there are also times when it’s hard for me to participate as an alloparent—to step in as a neighbor or aunt or church leader when it already feels like my job as a mother takes so much from me mentally, emotionally, and physically. But that’s the beauty of our ancient, eternal, human family. We’ve always needed each other. The task of parenting doesn’t feel so herculean when I see so many shoulders around me ready to help with the yoke. And when my burden feels a little lighter, it gives me the opportunity to look around and see who might need an extra set of hands in their pew.

Historian Stephanie Coontz noted, “Children do best in societies where childrearing is considered too important to be left entirely to parents.” I consider The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to be one of these societies. In fact, James E. Faust said of child-rearing, “To me, there is no more important human effort.” We weren’t meant to go through life alone. And we weren’t meant to parent alone, either. We need partners in our efforts—in the Church, in our neighborhoods, and in our communities. And we need to be that support to others, as well. Because it is only with this kind of selfless love and familial trust pollinating the branches of our eternal family tree that human society can flourish.

Jeanine Bee is the fiction editor for Wayfare and a Pushcart Prize–nominated writer. Her writing has been featured in places such as Exponent II, Irreantum, and Dialogue. She lives in Utah with her husband and four kids.

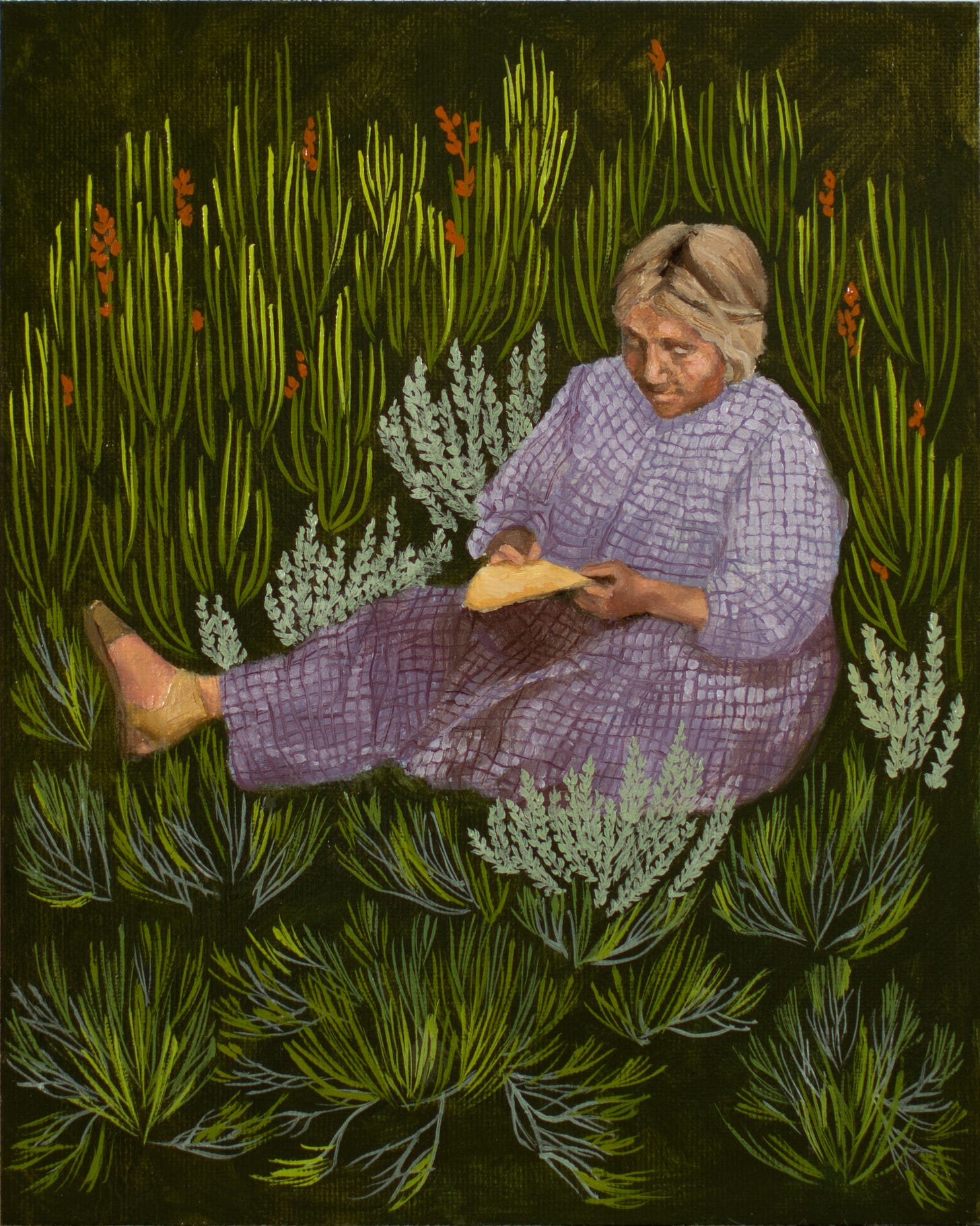

Art by Brook Bowen.