Community in America has grown harder to find. The spaces and institutions that used to gather neighbors together are in decline, while loneliness, depression, and other social ills are on the rise. As Seth Kaplan and Pete Davis explain, a healthy country is built on healthy relationships, and healthy relationships are built on commitment.

Relearning how to commit ourselves to a place and a group of people — especially our neighbors — is one of the best things we can do for ourselves and others. This episode of Article 13 offers practical guidance for how we can make these commitments and first-hand accounts of how joyful it can be when we do.

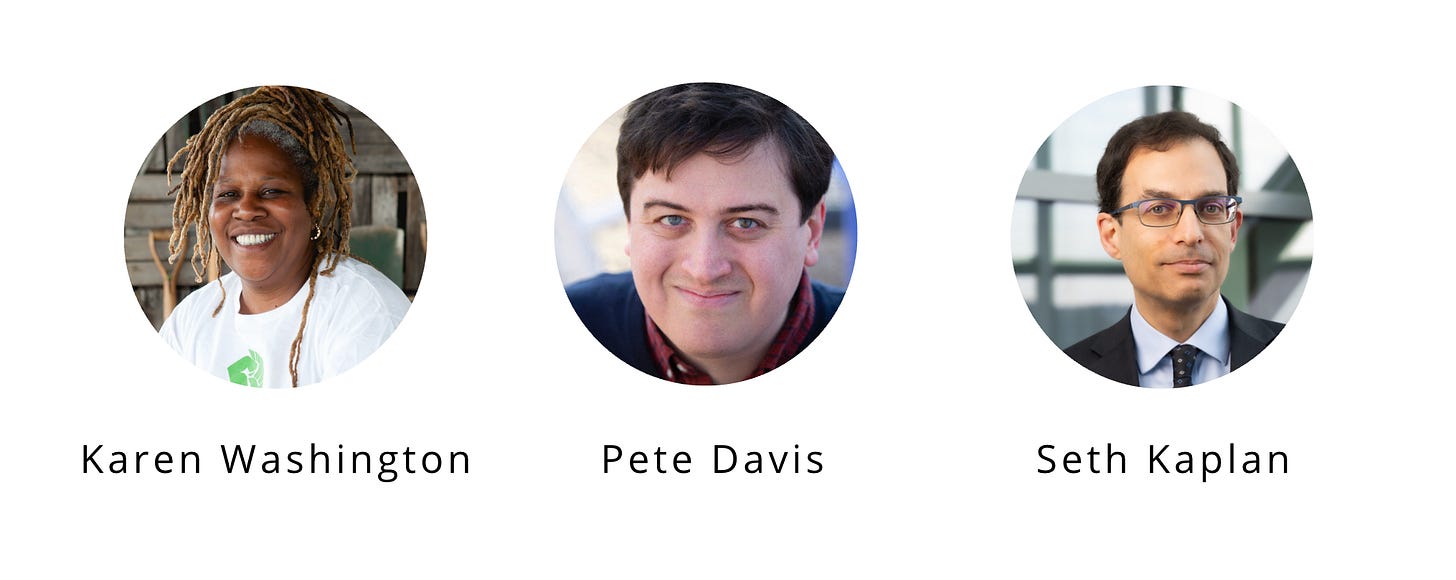

FEATURED VOICES

Pete Davis is a writer and civic advocate from Falls Church, Virginia. His Harvard Law School graduation speech, “A Counterculture of Commitment,” has been viewed more than 30 million times — and was recently expanded into a book: Dedicated: The Case for Commitment in An Age of Infinite Browsing.

Seth Kaplan is a leading expert on fragile states. He is a Professorial Lecturer in the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University, Senior Adviser for the Institute for Integrated Transitions (IFIT), and consultant to multilateral organizations such as the World Bank, U.S. State Department, U.S. Agency for International Development, and OECD as well as developing country governments and NGOs.

Karen Washington is a farmer and activist. She is Co-Owner/Farmer at Rise & Root Farm in Chester New York. As an activist and food advocate, in 2010, she co-founded Black Urban Growers (BUGS) an organization supporting growers in both urban and rural settings. In 2012 Ebony magazine voted her one of their 100 most influential African Americans in the country and in 2014 she was the recipient of the James Beard Leadership Award. Karen serves on the boards of the New York Botanical Gardens, Why Hunger, Just Food, and Farm School NYC.

LISTEN ON APPLE OR SPOTIFY

TRANSCRIPT

Introduction

Karen Washington was a physical therapist and a single mom who dreamed of having her own house in the Bronx. She was able to make this dream come true – but it turned into what she called “a nightmare” because of the abandoned lot across from her home. It began filling with garbage, got infested with rats, and became a place where “bad things happened.” But her story turned into a different kind of dream when she saw a neighbor, Jose Lugo.

Davis: She told me that my eyes lit up like a Christmas tree and she said, “What are you doing? And he says, “I’m trying to clear the trash to plant a community garden. Do you want to help?” And she said, “Yes, can I help?”

This is author Pete Davis, who related Washington’s story in his book Dedicated: The Case for Commitment in an Age of Infinite Browsing.

Davis: And what they did is they started organizing the whole neighborhood, they cleared all the trash, they started planting, and suddenly they had a garden with corn and squash and kale and collard beans and cantaloupe. Eventually, they got connected with all the other people doing community gardens all across the city.

Washington: Welcome to the Farmer’s Market, the La Familia Farmer’s Market.

This is Washington in a ParentEarth feature, describing how the garden became the launching point for a farmer’s market

Washington: We sat down, mapped it out, and then got four farmers who were willing to come to our neighborhood and got it started, so now we’re eight years in the making, love our community, community loves us, they wait for July to November to come on Tuesdays.

The garden also became Karen Washington’s launching point for new kinds of involvement in her community.

Davis: She started asking about the life of different people who are hanging out in the garden. And they said, “Oh, you know, we got this issue at school. We got this issue with hunger.” And then that got her involved in school issues and hunger issues and, How could the garden help with this?

Washington: Many families that I’ve talked to, just in passing at the Farmer’s Market, said, ‘You know, my kids were eating candy and cookies, and so when, you know, I started going to the Farmer’s Market and getting my kids involved in community gardening and eating healthy lunches, then I started to see a change and really saw how my children really started to like fresh food versus processed food.’

Karen Washington’s story is beautiful. More than that, it’s a beautiful vision of the kind of life we might wish for ourselves. A life of community. A life of meaningful connection to others, built around common projects and mutual care. Unfortunately, for many Americans, such life in community feels more and more out of reach.

Welcome to Article 13, a podcast that brings together cutting edge research and spiritual wisdom to provide blueprints for a better world. I’m your host, Zachary Davis. In this episode, we look at why community is declining in America and why this is partly caused by our own fear. We also take a deeper look at why community matters and how we can help bring our own communities back to life.

The disappearance of community

Community was once America’s great strength. When French political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville made his study of America in the 1830s, he was particularly struck by how readily Americans formed associations. These were, he said, “of a thousand different types … religious, moral …. very general and very limited, immensely large and very minute.” “Nothing, in my view,” he wrote, “deserves more attention than the intellectual and moral associations in America.”

This drive to associate also showed up for generations in how Americans inhabited their own local communities.

Kaplan: So if we’re thinking that America had a pretty healthy society two generations ago and we don’t have a healthy society now, what has changed?

This is Seth Kaplan, the author of Fragile Neighborhoods: Repairing American Society One Zip Code at a Time.

Kaplan: Until about two generations ago, people were very place-based, where they prayed, where they shopped, where they met people, everything was pretty close. So if you went, let’s say, in the 1950s or even into the 60s, and you went into a street, kids played on the street, parents hang out on their porch, they knew each other, and again it doesn’t mean that they were friends, but they had relationships, they had expectations that each other would be there to support them. I think this was the norm mostly everywhere until recently.

“Over the last two generations,” Kaplan wrote for After Babel, “the U.S. has moved from a ‘townshipped’ society in which neighbors regularly communicated and collaborated with each other … to a ‘networked’ and technologically-driven one in which local neighborhoods, schools, churches, and civic organizations are less important, and … have weakened over time.”

Two of those key features Kaplan describes – institutions and place-based community – have disappeared. The physical spaces that used to bring Americans together don’t exist the same way.

Davis: We’re seeing a decline in what are called third spaces. A third space is a place where you meet in community – a plaza, a park, a library, a cafe, a bar. If we see a decline in those spaces, you’re also going to see a decline in community.

Kaplan: I’m thinking, 10-minute drive from where I live, wonderfully nice houses – there’s nothing that connects those people, there’s just roads. Where are the institutions that bring those people together? You drive to church, you drive to school, you drive shopping, your civic engagement is not local, there’s nothing that brings people together.

The country has also lost many of the associations, like unions and civic groups, that used to gather people together.

Kaplan: And so, when I say fragile neighborhoods, I first and foremost mean places in which relationships are weak, institutions have thinned out or disappeared, and people just live next to each other and they have very little that brings them together.

And with nothing bringing us together, it’s no surprise that we aren’t getting together. Between 2003 and 2022, hours of face-to-face socializing declined for American men by 30 percent; for unmarried Americans by over 35 percent; and for teenagers by over 45 percent. As Derek Thompson writes, “there is no statistical record of any other period in U.S. history when people have spent more time on their own.”

And in particular, we’re not spending time with the people who share our local space. The Institute for Family Studies reports of recent surveys, “only a quarter of Americans said that they know most of their neighbors … The share of Americans who spend a social evening with a neighbor at least several times per month has declined from 44% in 1974 to 28% in 2022.”

Davis: We’ve started seeing community as less of a key part of our life. We think it’s all about what we do with our immediate family, nuclear family, and what we do with our careers, and there’s been a decline in this other huge part of our life, which is our interactions with friends, neighbors, and fellow citizens in community life.

And this decline in community has taken a visible toll on American life. Writes Thompson, “solitude, anxiety, and dissatisfaction seem to be rising in lockstep. Surveys show that Americans … have never been more anxious about their own lives or more depressed about the future of the country.”

Why community matters

What such data reveals is that community isn’t just one good thing among others. It’s a prerequisite for many, many other vital goods, for both individuals and societies – something Seth Kaplan, as a global analyst, is uniquely positioned to see.

Kaplan: My lens for thinking about this question is always the idea that relationships is the starting point for understanding any country. When I work in Libya, I work in Nigeria, I work in the United States, we must always remember that the nature of relationships informs institutions, affects politics, society, economics. And so the question is, How much love and how much security are people feeling in their relationships?

The relationships that build and define community also define how much people will thrive in many other areas of their lives. As place-based community has declined – as we participate less in local decision-making; as we see and trust our neighbors less; as we have fewer people around us who know us and look out for us – a plethora of social ills has increased.

Kaplan: Your neighborhood determines so much about what goes on in the social life and what goes on indirectly on how you are feeling and everything about your life.

Kaplan: We’re anxious because we don’t know our neighbors. Most people, they have no one to go to who’s near them, they’re afraid to let their kids out, they’re safeguarding themselves day to day – your whole mindset changes, your feeling of joy and happiness is not there because you feel alone and at risk.

Kaplan: My argument is that everything from deaths of despair to depression to the problems we have with lots of youth to the problems of mistrust and polarization, these lie downstream from how our relationships have changed in neighborhoods.

You may be one of those many Americans who feels alone and at risk, who doesn’t have a community to support them the way most Americans once did. If so, you may also be wondering how you could possibly address this problem when there are so many vast, structural reasons behind it.

But there is, in fact, a reason behind community decline that lies much more in our individual choices. It’s what drove Pete Davis to write his book Dedicated.

Davis: I was trying to think of, What is going on, what is the first step that would be needed to start rejuvenating civic life in America or communal life in America? And what is our resistance to that first step?

And when I reflected on it, what kept coming to me was the idea that we are scared of making the commitments that are required to sustain civic life – because civic life is made up of a series of commitments. It’s a book club, the basic unit of civic life, or a neighborhood association or a block party that happens every year – it involves you getting involved in something and tying your future down a bit. You know, ‘Every first Thursday of every month I’m gonna go to the book club meeting,’ or ‘I’m going to make a commitment to be there for the block party and help set up beforehand’ – all of that requires going against what I’ve identified as the central creed of our time, which is keeping your options open. If we’re maximizing keeping our options open, we’re never going to be able to make the commitments that are required to build the building blocks of civic life, which is committed relationships and organizations.

Community stopped being a priority for many Americans in part because another priority took its place – an emphasis on maximizing one’s own individual possibilities and opportunities.

Davis: The dominant message people my age were receiving – and I sometimes call it the creed of our time – is the message of ‘Keep your options open. Don’t commit to anything because you never know when you’ll need to be in a different place or with a different person or part of a different group or working on a different cause. Keep your options open.’

According to Kaplan, “A community requires a commitment to a certain social order—and usually to a place—that, by definition, must constrain some choices … In return for security, support, and belonging, members surrender some of their freedom.” Kaplan found the same thing Davis did: “creating community in America today is so difficult [because] few want to compromise their ability to make choices.”

But the problem with always trying to “keep your options open” means there is one option you will never have at all – the option to experience life in a rich, supportive community. That option only becomes available, as Kaplan notes, with commitment.

Davis: We have a fear of regret that in our one precious life, we’re going to commit to one thing and we should have committed to another thing – in fact, we are going to regret not making a commitment. We’re going to miss out on the depths of all the deep commitments we were going to make, and we’re not going to build the types of deep identities that root us if we never make a commitment.

Here we do find something that lies within our own choice: choices about how we invest our own commitments. If we want to rebuild community, we can start by rededicating ourselves to the people and places closest to us.

How can you rebuild community?

Kaplan: First you can look out your door, and you can imagine there’s probably eight or ten houses right there, and the first thing you could simply do is you could knock on a few doors. I will guess that if you tried eight or ten houses, you might not always succeed, but I bet you’ll find one or two houses where they will be open to something, and that is a starting point.

Once you meet a few people, the possibility of group activities opens up.

Kaplan: Can you have a block party, can you invite some people over for a meal – but of course, it’s always easier if you have one or two other people with you. Imagine there were three of you!

Kaplan: It’s best not to tackle loneliness alone. Can you find two, three, four other people in your broader area – it may not be in your immediate neighborhood – who care about these issues, and can you cooperate with them to do something, because if you can get just a few people who say, ‘We care, we want to activate that good nature or that desire to be with other people and among our neighbors,’ and a few of you do something together, it can have a cascading effect.

Kaplan: So I’d be looking for those few neighbors, I’d be looking for, What activity can you start, can you repeat that activity?

The repetition part is absolutely key, as Davis’s research showed. To build community, you need to commit to showing up for certain things again and again.

Davis: The way beautiful things are cultivated is usually through routines and routine gatherings and meetings. So you’re probably not cultivating something unless the most significant thing is, the third Thursday of every month and are sitting together and desire to do something together. So I think that’s a huge part of the story of community life, because the basic building block of community life is a relationship, and one of the key things that goes into a relationship is a little bit of commitment.

Now, that first step can feel daunting. It’s not easy to knock on a stranger’s door – even if that stranger lives next door. One thing that might help is asking yourself how they might be feeling lonely too.

In 2023, the New York Times created a video to give “voice to the lonely.” Americans shared stories like these.

“I was important, right? I mattered to people. I thought I did. And then I retired. And the isolation was deafening.”

“You look at the time and you go, ‘It’s 3:00,’ and you have so much of your day, and the phone doesn’t ring. No one’s connecting with you, and you wonder how you can make the day go by.”

“If I can get myself to pick up the phone and call somebody, somebody else will say, ‘I’m feeling exactly the same way.’ And then — poof! — you’re part of the human race again.”

Davis: I am more confident of this than almost anything, that is, the case of being communal today: almost everyone is sitting alone, wishing someone would knock on their door to come connect.

Consider how welcome a knock on the door might be, and that might make it easier to go ahead and knock. And when you do, keep this recommendation in mind.

Trailer, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood: “Sometimes we have to ask for help and that’s okay. I think the best thing we can do is to let people know that each one of them is precious.”

“Hey Mr. Rogers! It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood, please won’t you be my neighbor.” “That was wonderful.”

In an interview with Classic FM about playing Fred Rogers in the film A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Tom Hanks was asked how to be a good neighbor. His answer included this advice: you should go around to the people next door, introduce yourself, and ask if they need any help. But it’s also very important that you ask them for help too.

Asking for help lets people know they’re needed. That they matter. And it binds you all together into a community that is, as Kaplan puts it, “willfully interdependent” – where everyone has a gift to offer and those gifts are in demand.

In fact, the best platform for building community is often some project that asks everyone to share their gifts and efforts – a project like cleaning up the vacant lot.

Kaplan: I tend to find [that] intentionally looking to meet people is not as good as if you are doing something with people, if you have a goal, we’re going to work together to help so-and-so.

Knocking on a neighbor’s door, joining an organization – these are things we could do this week. Other changes will take longer but are no less important. One such change involves rethinking “the American dream.”

Kaplan: The American dream, originally, when this term first came into fashion, we’re talking, I believe, the Progressive Era, it was about uplifting people, uplifting all of society. Somehow we went from a more societal world view to a worldview that’s very individual and very material.

In a 2012 study, psychologist Jean Twenge examined three generations of Americans: Boomers, born post-1945; GenX’ers, born post-1961; and Millennials, born post-1981. The study found that, compared to Boomers, GenX’ers and Millennials placed a higher priority on life-goals connected to money and status, and a lower priority on goals connected to affiliation and community. Kaplan believes we need to change these priorities. We need to aspire toward social wealth as much or more than material wealth.

Kaplan: If we all think about ourselves and we all think materially, a great many of us are going to be left behind, and a great many of us may chase that dream and end up in much worse shape. We may end up lonelier, we may end up more depressed. We may end up in that nice house but all alone, and that’s not a recipe for a successful life.

What’s needed, says Kaplan, is a substantial shift in our goals. Many people right now aspire to go far away to college and then do a nation-wide career search, seeking jobs in cities like New York, Los Angeles, or Washington D.C. Instead, we should expand our sights: consider settling in places like the American Heartland, in smaller towns where we can get to know people better, or even back in our hometowns. We can adapt our work lives around our community lives. This is Kaplan with Shelley Doyle on her podcast “The Communiverse.”

Kaplan: I have a former classmate, not a classmate, a student, she says, ‘I’m moving back to Cleveland, I can continue my career, I can do it all virtually, I can fly when I need to, and I’ll live near my parents. because we have a better community in Cleveland.’ And we can stay invested in smaller places, places where people actually know each other, care for each other.

[Doyle] There’s definitely been a theme that’s been running through my recent conversations about the return called ‘Hero’s journey,’ and so many of us go on this big worldwide exploration, only to really feel the yearning to return, but returning with fresh eyes.

In 2023, the American Immigration Council and OverZero did a study on belonging. They found that feeling you belong means you experience decreased pain, stress, and loneliness; better general health; and greater satisfaction in life overall. But the study also found that “A majority of Americans report non-belonging … 64% of Americans reported non-belonging in the workplace, 68% in the nation, and 74% in their local community.”

As you plan for your future, make this something you consider: where can you feel that you belong? Where can you know others and be known? Where can you build and share social wealth? Finding the right community may well add more happiness to your life and your family’s than following the topmost job or moving to the most cutting-edge city. As you’re making big life choices, ask yourself, in what kind of community will this choice place me?

What joyful community looks like

The work of rebuilding community will take time. Progress will start off slow. But what Pete Davis found is that small changes build momentum. As one person shares their vision, others catch it and join in. And for those people who do dedicate themselves to cultivating the life of one neighborhood or one place, this long-term effort is often a long period of joy.

Davis: I was noticing that there were people who were full of purpose. They felt full of community, they were connected with all these people. They felt like they were living a really deep life. They were having an impact, [and they were feeling a lot of joy while having an impact, and] they completely ignored the advice of keeping your options open. They committed to particular things, they committed to causes, they committed to places, they committed to communities.

“Joy” is also how Seth Kaplan describes how he feels around his neighbors.

Kaplan: These are people, we are all together, helping each other, we feel like we live in a common boat, so to speak, we’re all going in the same direction, and we just have this norm that we’re here to be there for each other. And it just – I walk down the streets in my neighborhood and I feel joyful. I don’t know how you feel, Russell, when you walk down the streets in your neighborhood, but I feel a sense of joy because I know who’s behind the doors, I know some of the good things and bad things they’re experiencing, I know their kids, I walk around and I always see somebody I know, and it’s a reality check, it’s a sense of support.

Kaplan has seen countless examples of such support in his neighborhood. One involved his young son, who fell on the cement one day and cut open his chin.

Kaplan: My wife picked him up and took off down the street, and she came back about a half an hour later and he was all bandaged up. So what did she do, she took off to the nearest nurse. I could probably name eight or ten nurses or doctor’s houses where nurses or doctors live. I vaguely know who they are, I’ve seen them, a couple of them I know a little better than the rest – it doesn’t matter, if I knock on their door and I have a problem, they’re going to be helpful, and that’s just the norm in my neighborhood.

Another example concerned a friend of his daughter’s who had to undergo chemotherapy:

Kaplan: Neighbors come together, this community, school, comes together, people come together to support. It’s doctors in the neighborhood, it’s people checking up on them, it’s people volunteering to help them, and it’s the type of social support they get that that girl feels so much confidence and encouragement. She even went away for a special camp for a week, something involving a nonprofit in my neighborhood, so they got help on many, many levels to get them through this crisis.

Living in this kind of neighborhood has changed the very way that Kaplan experiences his life.

Kaplan: When you live in a security blanket and you have all these other people in there with you, your whole sense of the possibilities, your whole sense of who you are, everything changes.

Kaplan: The key thing is people need love. I mean, it’s such the most basic concept, we need love. I live in a neighborhood where I have a couple of good friends but I have hundreds of neighbors that I just have enough of a relationship with that we trust each other, we’re there for each other.

“Unconditional love is transformative,” said Kaplan in one talk, “and very few, too few Americans are experiencing it.” We can help transform our communities – and the lives of our neighbors – if we are willing to step forward and offer some of that love. That’s what Karen Washington did when she saw that trash piling up in her neighborhood. It’s what we can do in our own neighborhoods. And it’s how we might find our own joy.

Davis: And I think there are some people that say, ‘We should give up and just accept life as trash.’ I think there are some people that say, ‘We should move away and try to search somewhere else where there’s not trash piling up.’ And then there’s a third way, which is to transform the world. And that’s what Karen [Washington] and Jose and others have done. And what they discover is not that it’s this kind of arduous thing where it’s like, ‘Oh, you got to do the hard work of doing this.’ It is hard work. But what you find is it’s usually a great adventure that becomes part of your identity. It becomes part of your heroic story of your own life. It introduces you to all these new interesting people who become your friends. It broadens your horizons. And suddenly you wake up, you know, 20 years later and you’re like, ‘Oh, I guess I’m the queen of urban growing.’ And that’s what life is like with any commitment. You’ve got to just dive in, run across the street and say, ‘Yes, can I help?’ And who knows where that adventure will take you?

Article 13 is a new narrative podcast from Faith Matters that brings together cutting-edge research and spiritual wisdom to offer blueprints for a better world. American society is fractured across political and cultural lines. Healing will not happen quickly or easily, but will require a sustained commitment to peaceful discussion and the development of new, creative frameworks for finding common ground.

Hosted by Zachary Davis and featuring deep-dives into vital social issues, extraordinary guests, and beautiful sound design, Article 13 aims to model the kind of hopeful, intelligent discourse our country needs—and to offer ways that each individual listener can start the healing, right where they are.

Article 13 is produced by Maria Devlin McNair, Zachary Davis, Gavin Feller, and Music by Steve LaRosa. Art by Charlotte Alba. You can learn more about Article 13 here.

We express our thanks to the Wheatley Institute for their support.