In 2002, my wife and I and our young family were preparing to move to Virginia for a job opportunity. We traveled from our home in Salt Lake City to southern Utah to visit my parents in advance of our move. By that point, my dad had been suffering from Alzheimer’s for several years and had also been diagnosed with chronic leukemia and Parkinson’s disease. He was physically deteriorating, and I sensed that it would be the last time I saw him before he passed away. Sometime after we arrived, he pulled me aside and explained to me that he was sick, he had a disease he could not pronounce, and he wanted a blessing. He said flatly that he wanted to be healed. He was asking for a miracle.

His request terrified me. I knew he was dying and I didn’t have faith that I could give him a blessing that would change that. Even still, when your dad asks you for a blessing in the simple faith of his Alzheimer’s condition, it does not seem right to tell him “no.” I agreed to give him a blessing but spent the rest of the visit putting it off until the day we left, when I could no longer avoid the inevitable.

It wasn’t that I don’t believe in miracles because I do. It’s just that I didn’t believe in the miracle my dad was asking for, and I wasn’t sure that even sincere prayer and all the faith I could muster could make me believe. I believed in the science of his various diagnoses. I trusted what I saw with my own eyes: that my dad could only shuffle around the house and his strength was clearly failing. No one can escape mortality’s end; all of us at some point must face the eternities. Sometimes, it seems, we are even “appointed unto death” despite how much faith we might have to be healed (D&C 42:48).

My dad and I had never been close. He was 53 years old when I was born, approximately the age of my peers’ grandparents. He was distant and uninvolved and sometimes unpredictably mean. Yet if he was in fact dying, I didn’t want to leave anything unsaid before he died. I didn’t want any regrets, any lingering unresolved resentments, or any forgiveness left unoffered. All of this only added to my dread.

I knew if Jesus were there I could trust in him to know what to do—to heal my dad if that was his will—but I certainly couldn’t trust myself. There was too much baggage, too much history, and too wide of a gap between my dad’s desire to be healed and my deeply fraught reticence. In hindsight, there were also important lessons for me to learn in the process. I’m still learning those lessons but wanted to share one in particular.

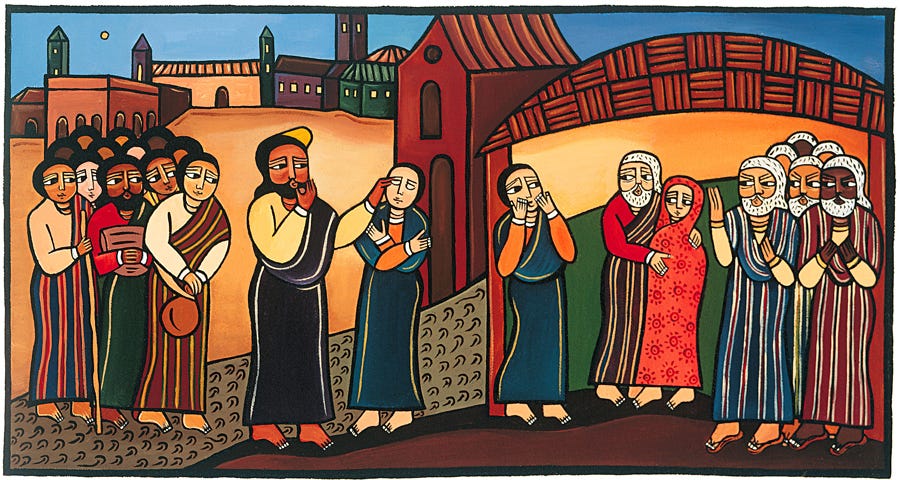

Of the miracles of Jesus in the New Testament, the one that captivates me the most is when Jesus heals the man who was born blind. He mixes his spit with dirt and anoints the man’s eyes with the resulting clay. He then tells the blind man to go wash the clay from his eyes in a nearby pool. As John puts it, the blind man “went his way therefore, and washed, and came seeing” (John 9:7, KJV).

On the surface this is a miracle about giving sight to a person born blind. That alone is satisfying to me because it corrects one of life’s seemingly random injustices or what Elder Renlund calls “Infuriating Unfairness.”

But, in my estimation, an even more intriguing aspect of the miracle is the way that Jesus uses this experience to correct cultural assumptions. His disciples attempted to fill in the gap between the blind man’s inability to see and the reason why he was born blind. Jesus’s disciples asked him, “Master, who did sin, this man, or his parents, that he was born blind?” (John 9:2, KJV).

Their question indicates an underlying assumption that blindness or physical disabilities or maybe any kind of differences are somehow a result of sin rather than the result of biological conditions outside of the man’s or his parents’ control. Jesus, however, rejected his disciples’ assumptions and replaced them with a paradox—a logically self-contradictory statement. “Neither this man nor his parents sinned,” Jesus declared, “but he was born blind in order that the works of God might be shown in him” (John 9:3, Wayment). Jesus suggests that a lifelong physical disability is not the result of sin but is in fact a manifestation of the works of God. Here, Jesus calls us away from easy cultural assumptions, longstanding and unchallenged explanations, prejudices, or simple bigotry. Instead, he invites us to see each other with spiritual eyes—to see each other as people in whom the works of God might be manifest.

Jesus often calls us away from trite explanations and easy answers. It makes me wonder who it is that we ascribe sin to today rather than looking for the works of God being manifest among us? I sometimes hear the cultural assumption that those who leave the church are only doing so because they want to sin. That judgment fails to acknowledge the depth of their faith journey or honor their right to worship “how, where, or what they may” (Article of Faith 11). We sometimes blithely write such people off as the separation of the wheat from the tares, with us self-righteously representing the wheat and them condescendingly becoming the tares. What if we let Jesus make those determinations, and we continue to tend to the entire wheat field with loving care?

What if we focused on our own sins instead of imagining sins for each other? As Paul reminded the Romans, “For all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23, KJV) and, “There is none righteous, no, not one” (Romans 3:10, KJV). As Pope Francis reminded Catholics, “The Eucharist [or in our case the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper] is not the reward of saints, but the bread of sinners.”

What if we washed the clay from our spiritual eyes so that we could view each other as people in whom the works of God might be manifest? What if we looked for the works of God in those who we sometimes relegate to the margins or treat as inferior—immigrants and refugees, women, our LGBTQ brothers and sisters, our single sisters and brothers, those who are disabled, and ethnic and racial minorities?

What if we opened our spiritual eyes to let Jesus resolve life’s paradoxes with paradoxes of his own? After all, Isaiah promised, “with his stripes we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5, KJV), a seemingly absurd paradox that lies at the heart of the miracle that is the Atonement of Jesus Christ. The stripes that tore at Jesus’s flesh are the same stripes that will heal us. The same blood that he shed in Gethsemane can wash our garments clean. “These are they which came out of great tribulation,” John the Revelator said, “and have washed their robes, and made them white in the blood of the Lamb” (Revelation 7:14, KJV). Blood by its very nature stains, yet when we wash our robes in Jesus’s blood, his grace scrubs them clean. Sometimes our choices or the choices of others create paradoxes that can wound our souls; Jesus responds with healing paradoxes all his own. His stripes can in fact heal us.

The miracle of the blind man is thus much more than restoring one man’s physical sight; it is really about inviting all of us to restore our spiritual sight—to wash away the clay from our eyes and to see each other as sons and daughters of heavenly parents each with our own divine potential.

Sometimes restoring our spiritual sight, however, can be long and difficult. It might involve years of blindness and longing for sight. It might involve spit and dirt and repeatedly washing the caked-on clay from our eyes. It may involve heartache, injustice, and pain. Let me illustrate with an example from my own experience.

It was a brisk morning when I climbed into the saddle, squished between the saddle horn and my dad. We didn’t have enough horses for everyone to ride their own. I was the youngest and smallest, so I rode double with my dad. My brothers took off in other directions to look for cattle. My dad and I rode up the draw between the mountain and the fence line, keeping our eyes peeled for any sign of cows and their calves. Occasionally, my dad spurred the horse into a trot and maintained an energetic pace.

As we rode along on this particular morning, he kicked the horse into a trot again and then slowed into a rapid walk. I can only think that it was the combination of the bracing air and the jolting stride that caused my nose to start to run. I didn’t have a tissue or a hankie handy, so in proper boy fashion, I started to sniff.

I never did ask my dad what set him off that day. We didn’t talk much, and he wasn’t particularly strong at introspection. Somehow he came to believe that I was crying. Maybe he thought that I was afraid because we had just trotted, or maybe he thought I was afraid because I was just me. I suppose his evidence was my sniffles, but he didn’t bother to ask.

“Stop your crying,” he yelled, as his gloved fist slammed into my face with no warning and with no escape. I don’t recall how many hits he got in that day, but the first one was solid and it hurt. I was trapped on the saddle in front of him with no place to run. I knew better than to protest or to try to explain: “I wasn’t crying dad, my nose was just running.” His mind was made up, and no amount of explanation could change things now. So I sat in frozen silence.

Now, when I had good reason to cry, I refused. I did not move; I did not talk; I did not cry. I was afraid of provoking another reaction, of fueling his anger all over again. My nose began to bleed. I saw the drops of blood hit the saddle horn while others landed on my shirt. I felt the warm blood run over my mouth and face. I made no effort to stop it, to sniff it, or even control it. I was paralyzed in dread and I did not want him to think I was crying again. At some point he noticed the blood and used his gloved hand to pinch my nose and get the bleeding to stop. I must have looked quite the mess when we arrived back at the corral.

“What happened to Walt?” my brother asked. “He gets bloody noses easily,” my dad replied. I really didn’t care at that point. I was just happy to get off the horse and get away from him.

Years later, now in my early twenties, I sat in stunned silence as my dad and his younger brother swapped stories at my uncle’s house one day. These were stories from their childhood, but not pleasant ones. They seemed to have forgotten I was there. I was home from BYU for a visit and my dad liked to go see his brother on those occasions. They got to talking and soon the stories of the abuse that they both suffered at the hands of their dad just spilled out. My grandpa was a man I only vaguely knew before he passed away but now my impressions of him were rapidly changing.

Learning of my dad’s upbringing provided needed context and new understanding. It did not justify his behavior but at least I had the beginnings of an explanation.

As a child I knew that my dad had endured a severe head injury as a result of a shrapnel wound to the head on the battlefields of World War II. A metal plate replaced missing skull fragments and he sometimes suffered from dull headaches. But it was only as an adult that I learned that head injuries frequently create a lack of impulse control in those who experience them. It was another missing puzzle piece. Explanation is not justification, but it did offer context and new answers.

On another visit home from college, I told my parents that I would teach the family home evening lesson. I used it as a forum to open up to them about some of my struggles, self-doubts, and lingering resentments. I recounted for my dad some of my more hurtful interactions with him and the type of repercussions that it had created. I had no idea how he would respond. I wasn’t very hopeful, but I wanted him to know. He listened patiently, did not interrupt, and seemed genuinely affected. He only spoke after I had finished:

“I’m sorry for how I disciplined you,” he said, “I learned it from my dad.”

I’ll carry those words with me for the rest of my life. I did not expect them. I did not think I’d ever hear them. They were God’s gift to me and a tiny bit of grace from a man I associated so strongly with justice. They floated from his heart to mine with healing in their wings. They lifted burdens and healed old wounds. It was the best thing my dad ever said to me. And he meant it. And I felt it.

I suspect saying “sorry” was also healing and helpful for my dad. He recognized his failings, recognized their connection to his own upbringing, and expressed regret. In my estimation, saying sorry is not a sign of weakness, but a signal of strength. I felt the power of my dad’s physical strength on several occasions in my youth, but he was never as strong to me as the day that he said he was sorry.

Thus, the day in 2002 when my dad asked me for a blessing, there was a long history that came to bear upon that moment. I did not feel capable of giving him the blessing he wanted. Yet Jesus still had a lesson for me to learn. Like the man born blind, he wanted to restore my spiritual sight.

When the Pharisees learned that Jesus had healed the blind man on Sunday they were upset. Speaking of Jesus, some of them said, “This man is not of God because he did not obey the Sabbath” (John 9:16, Wayment). They continued to question the formerly blind man, but it did not produce their hoped-for results. In response, the Pharisees stuck with their well-worn cultural explanations. “You were born entirely in sin,” they told the formerly blind man and then they threw him out of their synagogue (John 9:34, Wayment). The formerly blind man had gained his physical sight but could not escape the label others had assigned him. Even though he was no longer blind, the Pharisees refused to abandon the tired title they had given him. He was still only a sinner to them with no hope for redemption. They trapped him in his past and then cast him out of their present.

What the Pharisees failed to recognize was their own blindness. They were so intent on being “the disciples of Moses” that when the very Messiah who they claimed to seek stood before them, they called him a sinner for healing a blind man on the Sabbath (John 9:28, Wayment). Jesus came to minister to the outcasts and the downtrodden, the very people that the Pharisees rejected. As John explains, “Jesus heard that they threw out [the formerly blind man],” and so Jesus went in search of the new outcast and “found him” and this time Jesus offered him spiritual sight. “Do you believe in the Son of Man?” Jesus asked. The formerly blind man answered with a question of his own, “Who is he, sir, that I might believe in him?” Jesus replied, “You have seen him, and the one speaking with you is he.” The formerly blind man immediately responded, “I believe Lord,” and he worshiped Jesus (John 9:35-38, Wayment).

Jesus thus healed the blind man’s physical and spiritual sight. It was another miracle, this time with eternal consequences.

When I finally laid my hands on my dad’s head before we left southern Utah to return to our home, I still didn’t want to give him that blessing. I didn’t know how to simultaneously offer him comfort but not make him promises I did not believe would be fulfilled. I stumbled over my words and stammered to speak until I finally gave myself over to the only words that came into my mind. “In the coming months,” I said to my dad, “you will run and not be weary, you will walk and not faint, and you will find wisdom and great treasures of knowledge, even hidden treasures” (see D&C 89:19-20). As I spoke those words, the spirit simultaneously reassured me that those words would bring comfort to my dad in the present and would also be fulfilled in the eternities.

My dad did not run over the course of the next few months and even stopped walking altogether. He was confined to a bed with my mom as his caregiver. For Christmas that year I wrote him a letter. In part, I said, “I love you, Dad. I forgive you. I harbor no ill will toward you. I am filled with love and compassion for you. You are a kind man with a generous heart. Thank you for being my dad.” He passed away less than two months later.

I am still washing the clay from my eyes. I am on a stumbling walk with God. Because of my life’s journey, however, I try to more frequently join with Susan Evans McCloud in asking, “Who am I to judge another when I walk imperfectly?” (Hymns, 220) I know all too well that in my quiet heart is hidden sorrow that the eye can’t see. When I take the time to try to heal my own spiritual blindness, I am more willing to learn the healer’s art and apply it to my interactions with others.

Like the formerly blind man who was cast out of church for the imagined sin of being healed on the Sabbath, Jesus seems to keep asking me, “Do you believe in the Son of Man?” And like the formerly blind man I continue to inquire, “Who is he sir, that I might believe in him?” “You have seen him,” Jesus responds, “his works are manifest in the mortal and imperfect people all around you.” “I believe, Lord,” I sometimes manage to only whisper. “With your stripes I am healed.” And so I keep coming back each Sunday to worship him and partake of the bread of sinners.

W. Paul Reeve's book, Religion of a Different Color (Oxford, 2015) received three best book awards. He is author of Let’s Talk About Race and Priesthood, published by Deseret Book in 2023, with a foreword by Darius Gray.

Through a Glass Darkly

My least favorite spring-cleaning assignment was picking up the pears—soggy, rotten, winter-logged pears that had fallen off our tree just before the first autumn freeze. The tree was unpruned, the pears bitter, so we didn’t pick them when they were ripe; we just let them pile up on the ground and gathered them up every Saturday before mowing the lawn. Usually, we got most of them before they were covered with snow, but there were always soft, darkened exceptions to be found the next March.

Thank you, Paul. This made me weep.

I shall use these thoughts to continue to fully forgive my father for his “perceived” failures in raising me. Thanking you for this thoughtful writing.