Vulnerability and Dependency

Imagining a Theology of Birth in 3 Nephi

The moments after the births of both of my children are foggy in my memory—my aching body melding asynchronously with the ferocity of consuming love. Once the frenzy of the final stages of delivery receded, there were a few moments of quiet as their tiny bodies nestled close to mine. I remember, both times, a moment of paralyzing anxiety. This is what absolute dependency looks like. They are entirely reliant on me. Mother and child are intertwined so permanently, yet with such fragile precariousness. We are desperately vulnerable. I wept in those early moments cradling their precious bodies, both in exhilaration at their hard-won being and in a strange sort of bittersweet sorrow that thus they were ushered into the world. This is it, I felt, the frightening descent, the uncertainty, the tug and hollowing, and the sure embrace. The smell of me is your lifeline, my darling. I am all you have, and I am so terribly insufficient.

Birth operates as a metaphor for the central concerns of many religious and spiritual traditions. In the vulnerability it presents, as well as its proximity to death, birth has a hazy relationship to the larger conditions of human fragility. We are born helpless. Infancy and childhood have long been liminal states in the myths and legends of countless cultures because of their precariousness. The vulnerability, dependency, and helplessness of birth serve as an example of the problems inherent to the mortal condition, particularly human suffering. Many major religious traditions are predominantly concerned with human and planetary suffering as a central theological problem, but conceptualize and answer the problem in different ways.

The Western Christian tradition has largely considered the problem of suffering and evil in individualistic, human terms: Humans suffer because they sin. This sinfulness can extend to intent beyond individual acts and even to the conditions of the mortal world as “fallen” (we sin, in other words, not necessarily because we are evil but because sin is part of the mortal, finite condition). Moreover, the Western philosophical tradition orients the individual soul always in relation to death. Sin, ultimately including the entire mortal condition, brings death. Only a Savior, possessing nonhuman power, can redeem these dual and intertwined problems. To solve the problem of sin and death rupturing life, Christ must be transcendent, or always above the mortal and finite; we might call this a transcendence paradigm. He mercifully condescends to meet us in our mortal condition, but his role is to move us beyond this condition.

Other traditions resonate with the problem of human suffering as a real problem, but view it in quite different terms. Buddhism, for example, understands suffering as the condition of mortality, but sees it coming from anxious attachment, an unwillingness to accept the great mystery of ultimate nothingness (Sunyata). The solution to the problem of suffering might be conceptualized as a realization of the “impermanency and transiency common to everything, including humans and nature.”1 Interdependence is the basis of reality in this paradigm, suggesting that no individual exists as a silo but rather in a web of relationship and dependence. Death is not the great end set against life, but the constant condition of Samsara, or the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Importantly, as Buddhist scholar Masao Abe writes, Samsara (the cycle of life and death) and Nirvana (which we might understand as salvation or redemption) happen on the same plane; they are ultimately the same thing. Nirvana is realized when one reaches the understanding of the simultaneous nature of being/nonbeing.2

As a Christian thinker making comparisons, my point is not to suggest that one religious paradigm is superior to another but to highlight the complexity of these questions.3 We agree that human suffering is a problem, but where does it come from? What does it mean? How do we escape it? For Christians, the central aspect of these questions has to do with the role of Christ: What is the purpose and the meaning of the cross, a symbol of supreme suffering? Why does it matter today? How ought we to think about what happened all those years ago?

I find the simplified Buddhist paradigm I have described above helpful for highlighting limits of the “traditional” problem-and-solution paradigm of Christianity. Importantly, the central contrast on the plane of that Western Christian paradigm is life in opposition to death. Jesus has to transcend both life and death to free us from the conditions of mortality. Yet does this square with the theology of incarnation, the radical embodiment of God through a mortal woman?

Philosopher Jennifer Banks writes:

Death has been humanity’s central defining experience, its deepest existential theme, more authoritative somehow than birth, and certainly more final. It is given that humans are mortal creatures who must wrestle with their mortality, that death is the horizon no one can avoid, despite constant attempts at evasion and postponement and despite the recurring fantasy of immortality. Birth, meanwhile, is what recedes into a hazy background, slipping back past the limits of memory, existing in that forgotten realm.

In Banks’s work, birth reorients paradigms of meaning, bringing new dimensions to projects of hope, political activism, and literature. As I tiptoed through the lives of the ghosts she surveys, I wondered how a philosophy of birth might resonate or collide with Christian theology. Our paradigms owe much to the influence of Western philosophy, which was shaped in tandem with Imperial Christianity. But are there echoes within the stories we have inherited of a different path, an orientation that might jolt us from familiarity?

I have been holding these questions for some years, but something inside of me buzzed awake a couple of weeks ago as I rocked my infant, his nose too congested to comfortably sleep on his back, and thought about the story of Jesus coming to the Americas.

In some ways, the story seems a perfect parallel to his ministry in Jerusalem. But something happens in the Americas that might radically shift our focus—something that entirely reorders and orients his ministry in the Americas and in the world. Echoing a scenario in the New Testament, Jesus calls the children to him.

Readers of the Book of Mormon know that children will feature prominently in Jesus’s visit (as opposed to a verse or two in the New Testament, children are center stage for several chapters of the Book of Mormon text). Several interpretations and responses to this fact offer an interpretation along these lines: Jesus focuses on children because he wants to (1) heal them from the trauma of what they have just lived through and (2) strengthen them to establish the church and live faithfully.4 Extrapolating from here, I think of a religion professor I once had who often said that the purpose of the covenant path is to keep us in line “until we are safely dead.” This is what Paulo Freire calls a “banking model” of education.5 In this paradigm, we need to inoculate our young people, fill them up with knowledge and protection so that they will be prepared to live faithfully, to fight the battles awaiting them. Jesus, then, is strengthening the children to ensure the next generation.

I am sympathetic to this interpretation, especially from the perspective of parents reading the text. How do we ensure our children’s safety? How do we ensure their happiness? I hear Lehi asking the same questions in his vision and interpretation of the iron rod. I feel the weight of longing for sure ground, for absolutes, for a firm enough foundation. Acutely and deeply, I feel the fear born so achingly of love. The smell of me is your lifeline, my darling. I am all you have, and I am so terribly insufficient.

When I return to the story, I see my own projections. I see my fears echoed in the interpretation I place upon it. Are we interpreting the story of Christ’s visit to the Americas, the story of his death, resurrection, and continued life, through the lens of the paradigm of transcendence, and how does this change the meaning of the story? Through the transcendence paradigm, we might say that Jesus comes to the people of the Book of Mormon to lift them from the ruptures caused by their own sin. Knowing they will ultimately fail, he comes to prepare and strengthen them. Through this lens, children are understood as potential adults; our concern is with what they will become. This is understandable, especially from an editorial position (Mormon compiles and comments on this story in the wake of genocide), but I wonder if it unintentionally bypasses the situatedness of the text. By focusing on children’s future roles in the context of their faith, the ministry is somewhat transactional—crudely put, it could be read as this for that. I don’t think this is wholly wrong, but I am not convinced that it captures the timbre of the narrative itself. Deeper, I wonder if this reading has the capacity to adequately speak to our contemporary suffering and woundedness. Here, I turn to the resources that a philosophy of birth offers and begin a translation to theology.

We know that children are dependent. It was almost gutting to me in the visceral moments of new-motherhood, feeling the precarious fragility of my infants wholly reliant on me. But I am not sure we always remember that we are all dependent. As Christian ethicist Sandra Sullivan-Dunbar writes,

Dependency is a central aspect of human existence. We begin life ensconced within and dependent upon the body of another human person, using her body as a source of nutrients, oxygen, warmth, and space. When we emerge into the world as a separate body, we remain utterly dependent upon other human beings to feed us, to keep us warm, to hold us, to talk to and socialize us, to protect us from harm. We are bodily dependent again when we are sick, or when we are disabled, and if we live to old age, we are often dependent on others in the frailty of our final years. And at those points in our lives when we seem most autonomous, we nevertheless remain deeply dependent on others in countless ways that we often fail to acknowledge.6

Dependence is a mortal constant, a condition of life. Our dependency situates us as mortals—we enter the world frail and helpless, and despite our best efforts, we remain dependent on external nourishment and relationships throughout our lives. We are not self-sufficient or autonomous, but vulnerable. Indeed, theologian Elizabeth O’Donnell Gandalfo argues that vulnerability, not sin, is our anthropological constant—our inherited condition of mortality.7 The problem is not sin as traditionally understood; the problem is how completely vulnerable we are, how terribly, fearfully dependent. A paradigm of transcendence suggests that this dependency, this vulnerability, is something to be overcome, to be transcended, and indeed I think of the many ways we try to deny our vulnerability. But when I read the stories of Jesus, when I imagine angels and elements together blessing children in language beyond words, I am not convinced. I think that Jesus embodies a theology of dependence and birth.

Birth begins Jesus’s story. The birth is as banal and ordinary as millions of others. The pain, the blood, the sweat, the woman’s body. He is born hungry and cold, like every one of us in the history of the world. He is born with flesh. He dies between thieves, a cruel and humiliating death but no more so than many millions of others the world over. His life is a human life.

But then, he comes back. What do we make of this? Why does he come back? And why does he visit the Americas? There are a thousand answers, all with truth. One strong category of answers belongs to the transcendence paradigm, in which Jesus’s return is triumphal. He comes back, in this rendering, to say that mortality is beneath his heel. The final victory is won. The problem—human sin and death—has been dealt with; the transcendence paradigm is a linear, triumphalist arc. I am representing here one articulation of a theme in which there are many variations. Triumph is comforting. Transcendence gives hope to many who feel paralyzed by the injustices of the world. But the arc of transcendence as a triumph misses the muddiness of the life below. In concert with transcendence, then, I want to engage with the human aspects of the story. I want to dwell with the way that Jesus retains the marks of flesh. The way Jesus calls the children to him and weeps for their woundedness. The way Jesus prays.

What would it mean if the resurrection of Jesus were not just a triumphal hymn of transcendence, but a lullaby? Jesus is not bypassing mortality; having overcome it, he is returning in solidarity. The difference between these things means everything to me. Jesus calls the children not because he wants to ensure that his church will survive for another generation, but because he aches for the vulnerability of these wounded innocents. What losses have they known? What destruction have they witnessed? Who did they cry out for at night? In calling the children, Jesus calls the vulnerable to the center of the narrative. And metaphorically, mythically calling forth the child in everyone who enters into the story, Jesus calls forward vulnerability. Jesus calls all that we try to disguise, to bury, and to protect. Jesus calls the children because this is his mission: birth. Life. Solidarity with our vulnerability. The establishment of a church is a second-order concern. Its function is to serve the first.

The story begins with vulnerability: a girl and her child. A lullaby, that first sleepless night, the star.

Death, agony, and then birth again.

This is the radical reorientation of the Christian story. Not death, but birth. Not forever life, but forever birth. Incarnation, God in flesh, Jesus calls the children. Gandalfo quotes Nicaraguan mother Idania Fernandez: “‘Mother’ does not mean being the woman who gives birth to or cares for a child; to be a mother is to feel in your own flesh the suffering of all the children, all the men, and all the young people who die as though they had come from your own womb.” Mother Jesus calls the children.8 In centering them in this narrative, Jesus shifts the entire thrust of the Christian message. Not victory over death, but solidarity with life. The children are not just a future generation of adults. The children are a representation of all of our human vulnerability.

And he spake unto the multitude, and said unto them: Behold your little ones. And as they looked to behold they cast their eyes towards heaven, and they saw the heavens open, and they saw angels descending out of heaven as it were in the midst of fire; and they came down and encircled those little ones about, and they were encircled about with fire; and the angels did minister unto them. (3 Ne. 17:23–24)

Behold your little ones. Behold your littleness. Behold your fear, your longing, your dashed hopes, your broken heart, your weary body. It is so beautiful, I wanted to sing to my children as they blinked and nursed and slept their first moments on earth. It is so terrible and so beautiful. There is so much I do not know. There is so much I am afraid of. Oh, but the flowers. The birds. Your hand in mine. Our eyes on the stars. Our mysterious place here in this finite moment. I will fail you. You will catch your breath at the sea. It will not be enough. The trees will grow, we will die. We will love it all. Child, welcome here. I love you. Forgive me. I’m here.

We trail off, humming a lullaby, gazing out into the unknown. Tomorrow is a fragile mystery. All is well.9

Kristen Blair is a practical theologian working on her PhD in Theology at the University of Toronto. She is focused on feminist interpretations of kenosis, exploring dimensions of submission, agency, and dependency. She loves good food, the good earth, and mothering her two babies.

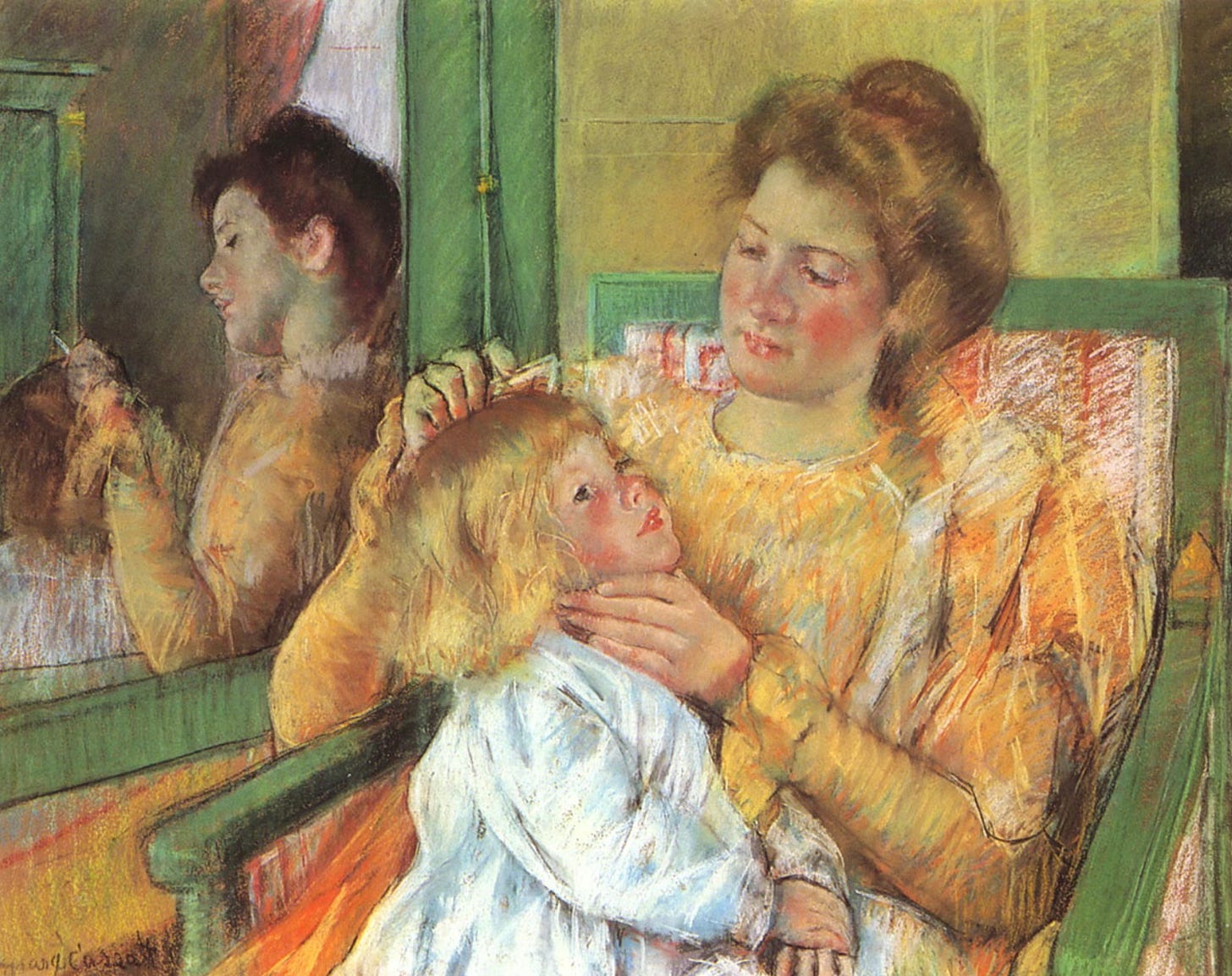

Art by Mary Cassatt (1844–1926)

KEEP READING

POETRY

Masao Abe, Divine Emptiness and Historical Fullness: A Buddhist-Jewish-Christian Conversation with Masao Abe, ed. Christopher Ives (Trinity Press International, 1995), 29.

Abe, Divine Emptiness and Historical Fullness, 45.

I’m inspired in this discussion by Michelle Voss Roberts’s book Body Parts: A Theological Anthropology (Fortress Press, 2017), where she says, “Awareness of the history of Christian engagement with other traditions might lead people to avoid studying them altogether. However, neglect of religious neighbors is another way to denigrate them, implying that their history, ideas, and contemporary contributions are not worth considering. The postcolonial (or, arguably neocolonial) moment calls for a different theological approach. The discipline of comparative theology provides one such option: comparative theologians aspire to represent other traditions accurately and responsibly, make well-informed comparisons, and remain open to learning from religious neighbors. Like all deep and prolonged theological work, comparative theology can contribute new ways to understand the doctrines of the church. As interreligious learning inspires new thought about the questions of one’s own faith tradition, constructive theology may emerge” (xxxii).

See, for example, M. Gawain Wells, “The Savior and the Children in 3 Nephi,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 1 (2005). See also “Why Are Children So Prominent in 3 Nephi?,” Scripture Central, August 21, 2019; and “Part 2 Ministering One by One: Reviewing Third Nephi 18–28,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Canada.

Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos, 50th anniversary ed. (Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

Sandra Sullivan-Dunbar, Human Dependency and Christian Ethics (Cambridge University Press, 2017), 1.

Elizabeth O’Donnell Gandolfo, The Power and Vulnerability of Love: A Theological Anthropology (Fortress Press, 2015).

Following Julian of Norwich here from her Revelations of Divine Love (Ixia Press, 2019), chapter 9.

Again, quoting Julian of Norwich from Revelations of Divine Love, chapter 9.

So very profound and inspiring. Thank you!