Voices from the Dust

Restoration Ethics at the End of Life

Physician-scientist, ethicist, and theologian Samuel Brown spent two decades studying questions of life and death before walking with his own wife, Kate Holbrook, through the valley of the shadow of death. In this address, originally delivered a month after Kate’s death as the keynote address for the Brigham Young University Bioethics Conference, he interweaves the story of their walk together with key insights from Restoration theology to re-cast and re-frame contemporary ethical controversies about medical care when life may be near its end.

I’d like to do two things during this talk. I want to make a narrative argument from my own life. And I want to make a philosophical argument. I’ll use the narrative argument as the scaffolding for the philosophical. In these braided arguments, we’ll talk about relationships, a Latter-day Saint inversion of Lucretius’s famous indifference to death, and the call to rescue. We’ll ask some hard questions of ourselves and our society and propose some possible answers. We’ll hear just enough history to orient ourselves to the problems at hand. For the most part, we’ll be solving problems rather than reviewing history.

The core of my thinking on this topic is that according to Restoration theology, we humans are agents with inherent dignity, that agency is expressed in human communities, and the goal, the telos, of that agency is to rescue each other from pain and suffering. These Restoration tenets underlie a new approach to questions about problems of care when life may be near its end.

In August 2012, my wife, Kate Holbrook, was running a conference on Women and Mormonism with her friend and collaborator Matt Bowman. During the conference, she began to lose sight in her left eye, but she pressed on to finish the weekend’s business. On Monday, we discovered that a rare cancer called uveal melanoma had lifted the retina off the back of her eye. This calamity disoriented us, but after a series of surgeries that replaced her eye with an elegant prosthesis, she learned to live without depth perception, and we found a new cadence to our lives. We undertook life with more gusto than before, even as a sword of Damocles dangled over our heads. The sword stretched lower every six months, when we performed surveillance scans to see whether the tumor had recurred. We had almost reached five years, the moment when one considers oneself free of a cancer, when a spot smaller than a dime appeared at the edge of her liver. Thus began a half decade living with Stage 4 melanoma, the kind called “metastatic,” meaning that the cancer has migrated from its original location. Uveal melanoma at this stage is essentially never cured. I was terrified by the prospect of life without Kate. She worried about being separated from us, but she was also concerned about what the dying process would be like. How much would she suffer? How hard would her wrapping up be on her, on all of us? What was there to fear, what to relish?

Data from multiple surveys suggests that people facing terminal illness worry the most about loss of autonomy. No one likes pain, no one likes nausea or vomiting. No one likes feeling that their body doesn’t work the way it’s supposed to. But what they fear most, and what seems to figure most often into personal decisions to request a suicide pill (where such pills are legal) is the fear that the suffering person would be a burden on others. This is not surprising in our contemporary world, with its rhetoric of individualism and self-sufficiency. That is, I believe, a fact worth grieving.

The COVID pandemic was hard on everyone I know. I’m aware that people in some pockets of the world feel that the pandemic was always only nervous posturing by city folk and alarmists, but I don’t know anyone who didn’t suffer during the pandemic. In addition to the pain and suffering of the infection itself, there was what the pandemic exposed in our world and the ways we treated each other. Bad decisions were made across the various political spectra.

I was asked to serve on a committee working to decide how best to share resources that might be severely limited: ventilators, ICU beds, and COVID-specific medicines. It was a strange time for everyone. After the images of a corpse-strewn Italian countryside and New York too full of cadavers to bury them all, we began the most prominent societal discussions we’ve had in a generation about what happens when need outstretches capacity. Kate, like everyone else, was curious to hear what was being discussed among professionals and policymakers. At the beginning of the pandemic, Kate was still in excellent health, all things considered, and felt great satisfaction in life.

Early in the process came a public proposal from the University of Pittsburgh on the question of rationing ventilators—how do you decide which patients will qualify? (In retrospect, we were asking the wrong question, as ICU clinicians were the bottleneck rather than ventilators, but that’s a story of hubris, technophilia, and myopia for another day.) What struck Kate most, something I had barely noticed, was that the Pittsburgh group were proposing that she—a woman with Stage 4 cancer—should not receive advanced life support if it was in short supply. I know and admire the people in Pittsburgh. They’re good people, striving to do right. And as their proposal underwent due scrutiny, it became apparent that they’d been lulled into a kind of trance by the music of the spirit of the age. It became clear that the Pittsburgh proposal was illegal and unethical; similar guidelines were revised to take into consideration the specific illness at hand—what’s the chance you’ll survive your COVID?—rather than the broader life story—what other diseases lie on your path ahead? Instead of classifying types of people who could or could not receive advanced care, the decision was made to grade the COVID illness itself. That was a better approach.

But the damage had already been done in our family. Kate was vulnerable in a way I’d never seen before. Her fear of COVID ran to the end of her life. I’m proud that we kept her safe from the virus through the ensuing two and a half years, but I’m sad to think of the anxiety she experienced based on the guidance from Pittsburgh that she was the wrong kind of person. That was the clear message the Pittsburgh proposal sent: you, in your vulnerability, do not deserve to survive a serious COVID illness. I saw people who, when they caught COVID, were reluctant to be treated because they had heard that they wouldn’t be treated anyway. The “no one with metastatic cancer gets a ventilator if they’re in short supply” statement was a casual, thoughtless error for professionals to make, but lay people experienced it very differently. Public rhetoric can have important ramifications. Countless similar messages circulate in our cultural world.

I know what it’s like to say something by accident that can affect someone else’s entire life. In the ICU we are constantly working with families to understand whether to continue on with intensive care or to instead let nature take its course. Over two decades I’ve participated in this process hundreds of times and have realized something of the rhythms of these conversations. It’s not what they teach you in medical school, and it doesn’t happen the way they pretend it does in ethics textbooks.

I quickly realized that my body language, the words I chose, whether I touched a hand or asked a specific question in a particular way could have life and death consequences. The ethicists were busy teaching us that the patient and family are self-determining and we clinicians are passive conduits for medical information to inform their consumer decisions. But I could see that was almost never the case. We work together, and if we clinicians aren’t careful, we shape the outcomes to fit our vision of the world rather than being true to the patient as a person. People feel and respond to dozens of contextual clues and messages, and those may matter more than anything else. Patients in distress are, in my experience, vastly sensitive to the contexts in which they must make decisions. Clinicians’ hopelessness can be contagious, as is our sense of what a life with limitations might mean.

These facts matter as we move toward discussions about care at the end of life. Context matters. Social cues matter. What we outsiders say and how we act can strongly shape the decisions patients make, even when we claim that we clinicians are supporting their autonomy. This reality is especially hazardous when it comes to questions about state-sanctioned suicide.

The fact that decisions—even or perhaps especially the weightiest ones—happen in human contexts and communities won’t surprise Restoration theologians. Nor should it surprise Latter-day Saint clinicians and patients. We are relentlessly embedded in communities. It’s a point of caricature about the Latter-day Saints and a common complaint in the modern age: Mormons are overwhelmingly communitarian. It’s what we do. This robust community is the shining jewel in the Restoration crown. We belong to each other. From whatever beginning to whatever end the universe has in store for us, we belong to each other.

I’ve written extensively in my historical and theological work on the fact that the core tenet, the nerve center, of Restoration theology is relation. Relation permeates every important aspect of Church and Gospel.

The founding scripture, the Book of Mormon, draws the voices of the dead from the dust to the ears of the living. It re-unites fractured Israel. It brings the Bible into new life among modern readers. It creates and sustains new relationships among people and among peoples.

Within a decade after the Book of Mormon came the Restoration theology of adoption. We probably know the idea best as the theological infrastructure of polygamy, but it’s vaster than that. It’s the theology of the Saviors on Mount Zion, of celestial marriage, of the City of Enoch. It’s the idea that we can bring priesthood and salvation to each other through parent-like relationships. And learning to interact with each other in the parent-like way of Christ is the core learning task for our mortal experience. The temple theology and ordinances come into being to make the adoption theology real throughout eternity. Certain rituals of adoption changed at the end of the nineteenth century, and we no longer speak as explicitly about “adoption” as such, but the core theology is unchanged. We belong to each other, worlds without end.

There is nothing more Latter-day Saint-ish than the transitions in the meaning of the word seal. Originally to seal meant to mark something as set apart for a king or a God. It then came to mean that one had a surety of salvation. A righteous believer was thus sealed up to salvation. But Joseph Smith was consistently clear that to be saved alone was indistinguishable from damnation. His mocking jest that he would rather go to hell with friends than face heaven alone was deadly serious. Joseph Smith never imagined, let alone revealed, a heaven of the isolated believer. By the time the Saints were done with it, the word seal had precisely the now familiar sense of being glued together in a way that not even death could dissolve. Sealing is a cement that holds us together rather than a clay tattoo that identifies us as God’s. Being sealed means being together. We are always in relation.

That being in relation takes work. Without great care, the vulnerable among us can be made even more vulnerable by the very relations that ought to support them. Especially when we are scared, uncertain, and uncomfortable, the work of relation can be perilous.

Our family and friends confronted Kate’s mortal end on several different occasions, separated by years. Masses in the upper arm caused nerve damage that proved to be innocuous lymph nodes and a stress injury. A tumor in the skull disappeared under a neurosurgeon’s drill and never returned. The cancer immunotherapy destroyed her pituitary gland, and she looked like she was weeks from death before the problem was diagnosed and repaired. Even in the setting of metastatic cancer, we were often wrong by years. Of the eight or ten experimental therapies she received within clinical trials, two of them had an obvious benefit, buying us about two and a half extra years. There was a lot of living to do in those 900 days, give or take.

As we confronted Kate’s last years, we all pondered what to do with ourselves. I had a big promotion at work that I could refuse if need be. Our oldest didn’t want to be on her mission while her mother lay dying. Our middle daughter was due to start college and wanted to know when and where to do it. Her mother’s impending death stalked our youngest at every turn. We all wondered how best and when to interrupt our lives to be fully present during Kate’s last times. We were glad to do it, even as our nerves could never settle.

In the event, our over-planning those months and years backfired.

After one such morose conversation, Kate winced, “When you talk about all this postponing, you make me want to just give up and die so that I’m not getting in the way.” That tearful rebuke got us better focused on doing the work of living while also walking with the dying beloved. We went about life while also trying to be as open to Kate’s living as we could be. That last year of her life was probably the hardest year of ours. But we stopped talking about the ways Kate’s wrapping up affected the timetables of our lives. There was just life and the living of it. And we had seen again that old truth: the many signals and messages we send to the vulnerable, whether we know it or not, have real effects.

We as a family were confronting a question just like millions of other people: What do we do with time that appears to take place in the twilight of a mortal life? In the last half century, with dramatic intensification in the last two decades, state-sponsored suicide has been proposed as a solution. Here the philosophical argument will come into clearer focus. As we set out, I will indicate why I’ve moved from being generally in favor of assisted suicide twenty years ago to now finding it a betrayal of fundamental, cherished values on both the Left and the Right.

We will want to orient ourselves to some of the history. The cultural arguments about suicide most relevant to us occurred in the setting of the development of hospice, which was an attempt to provide specialized care to people who are actively dying. The Swiss-American psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler Ross is famous for her 1969 book On Death and Dying and what has come to be seen as a taxonomy of grief. The concept of stages of grief or even emotional stages of dying has not stood the test of time particularly well. And Kubler-Ross was an odd character who got tangled up in spiritualism after she got famous. But what she should be best known for is her shock at discovering, when she came to the United States, that the dying were lonely and hollowed out, locked in private rooms on hospital wards, with no meaningful human contact and no discussion of the possible meanings of their lives before and after death. She battled hard for the dying to rejoin the living. While she did not found the hospice movement—credit for that is normally given to Dame Cicely Saunders—Kubler-Ross’s careful advocacy facilitated the dramatic expansion of hospice in the 1970s and 1980s. The dying began to receive help and respect.

Suicide, for its part, has a long history. Several of the precedents employed in contemporary discussions are from the ancient Greek and Roman worlds. Suicide was a well-recognized mode of departing life in those societies; some eloquent thinkers and statesmen spoke of it in positive, even reverential terms. Especially the Stoic philosophers, Seneca most famous among them, favored suicide in certain circumstances, seeing it as an expression of agency and a promise of escape when life was too much.

There’s been a resurgence of interest in Stoic teachings on suicide in our late modern world. I’m surprised that these would be precedents of interest to us. The society the Stoics inhabited was unbelievably brutal when compared to ours. Executions and torture were frequent; women were widely demeaned, exploited, and assaulted; slavery was rampant. I’m not trying to poison the well, but instead to call out the lived context of antique claims in favor of suicide. While Seneca spoke of the “freedom” imparted by killing oneself, it was generally the freedom to escape a situation made intolerable by a society that had outgrown its use for you. Often—think Socrates—suicide was a form of execution that forced the condemned to take active part in the violence. The fantastically cruel world of antique paganism is no well of compassion and dignity for the vulnerable. It was the brutal opposite. When society felt that the rest of a person’s life was not worth living, society persuasively achieved its purpose. That, in a nutshell, is antique pagan suicide.

But there were other cultural currents flowing in the 1960s and 1970s, especially relating to competing visions of reproductive freedom and responsibility. The culture wars around abortion were never far from questions about the sanctity of life near its end. There is so much surrounding pregnancy and parenthood and the vulnerability of women and expressions of sexuality tied up in abortion debates that we can lose track of the effects of these debates on public perceptions of suicide. Often, when people heard religious concerns about suicide as a violation of the sanctity of life, they saw a thinly veiled attack on abortion rights. But these are separable questions—our beliefs about abortion may have little to do with thinking about suicide.

Questions about suicide, where a dying person is an active agent in their own death, and about euthanasia, where someone else is that agent, were also wrapped up in societal debates about what to do with people who had suffered devastating brain injuries and were maintained by artificial means in healthcare facilities. Few felt that we should be forcing physicians to maintain permanently unconscious individuals on life support systems for years. The most extreme voices on the Right said that any refusal of medical treatments was “passive euthanasia” and ought to be forbidden. But most people felt that letting nature take its course was appropriate in at least some circumstances. The rhetorical counter-response from certain ethicists was to erode the distinction between “killing” and “letting die.” If letting die is reasonable, and most Americans agreed that it was, then why not go all the way to sponsored suicide and euthanasia?

Given this historical context, it’s not surprising that many of us retreat into the vitalism vs. secularism camps when it comes to assisted suicide. Vitalism is the life-above-all-else approach modeled by conservative Catholics and Evangelicals. Secularism has tended to emphasize ancient pagan approaches to suicide, in the context of the modern emphasis on individual autonomy or self-determination. The course of the culture wars has meant that both sides have taken positions that are frankly inconsistent with their ideals. I’m particularly struck by the fact that when pro-suicide campaigners argue against the Christian emphasis on the sanctity of life, they are rejecting the core tenet of modern liberalism: the lives of the marginalized, the weak, the vulnerable matter. This love of weaklings and slaves is something neo-pagans like Nietzsche couldn’t stomach, but Jesus said that even the least of people contained a divine spark that required our reverence. As the Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart has reminded us, this is the Christian religious innovation that undergirds the core impulse of the modern Left: deep respect and empathy for the vulnerable. Remember that fact as we consider our obligations to each other in the context of debates about state-sanctioned suicide.

Fortunately, Latter-day Saints and the Restoration theology that supports them are neither vitalist nor secularist, although they honor the good in each of those philosophical systems. Restoration theology is not inherently conservative or liberal as those terms are now used in the United States. Instead, the relational nature of Restoration theology leaves open pathways better attuned to life’s complexities. And life is complex, especially when it is near its end.

Kate was suddenly near death the week of August 1, 2022. But our youngest child was not yet home from her residential school, and Kate and I wanted very much for that child to be able to participate in her mother’s closing scenes. So Kate agreed to be hospitalized and to receive treatments that would extend her life. She came home August 5, having gathered some strength for the final stretch. Our daughter arrived August 10. Kate entered hospice on August 11; she died on August 20.

We worked together to figure out how to meet needs that she once managed for herself. Kate kept working for her first two days on hospice but then couldn’t continue. She slept more each day. We increased her pain medicine and focused on other medicines for comfort. She became delirious in the last few days, waking up and asking sweetly confused questions. Then, as is typical with delirium, she would be fully awake and engaged for a blessed hour. Her generally private nature opened up some; she laughed alongside the grimacing. One evening we spent a couple hours with close friends and my sister. Kate rested her head on my lap in the intimacy of vulnerable self-giving that we hadn’t managed well in married life. As I helped her walk to bed, she told me how much she loved that quiet time together.

As we navigated those last two weeks, I wondered whether she would reconsider her conviction that suicide was not the right answer to the vulnerability of dying. Even though the pain was worse than she expected, she did not change her mind. She continued on with what time she had, working both to control her uncomfortable symptoms and to support and love her community.

I also wondered whether my convictions would fade. I’m not proud of every aspect of those closing scenes of her mortal experience. I’d always told myself I would take a leave from my job when the time came, but there I was in early August trying to juggle my work calendar and supporting Kate. I had stopped all routine meetings, but I was continuing to meet with senior leadership from time to time. As I was explaining why I had to step away for a moment for work, she pleaded, “You promised you would stop.” Realizing that I had failed her hurt the most. So I stopped work entirely for her last two weeks of life.

Even as I focused my efforts more purely and thoroughly, I found myself sometimes wishing she were dead. It was all just so hard and tiring and confusing. We were living in Purgatory. My emotional strength was exhausted. Particularly in her last hour of life, as her now unconscious body moaned in the discomfiting breath of a brainstem starved for oxygen. I sought whatever medicines from our hospice kit would reassure me that she was comfortable. I told myself that it was for her that I wished the end would come, but I knew that it was for me.

Despite these many misgivings, I soldiered on. Those last days and hours were sacred and lovely, the best time I’ve perhaps ever spent.

My conflicted feelings as a cancer husband to a beloved wife reminded me of a terrible fact we physicians aren’t comfortable admitting, even to ourselves. When the prospects for recovery are poor, we sometimes passively wish that a patient might die. It can be difficult to stay committed to the care of a patient with a high chance of death. And, particularly in the ICU, you can feel like the treatments themselves are a kind of torture. So, we sometimes think, maybe this patient would be better off dead. As the middle-aged professor I watch the young doctors now, and I notice that they often start to talk about futility and stopping treatment when the odds of survival drop much below 50-50. We should be clear: a 50% mortality rate is dire straits. But few if any people would refuse treatment, let alone wish to be euthanized, on the basis of such odds.

Early in my work on humanizing the ICU, I asked the same question of two groups of people: doctors and nurses on the one hand and laypeople on the other. I asked them to tell me what odds of recovery they would need before willingly submitting to an intensely painful treatment. How good would their chances need to be, in other words, for them to undergo torture for three months? It’s a weird question, but people understood immediately what I was asking. The healthcare workers gave numbers between 10% and 50%. Not even one of the laypeople I spoke with went above 1%. Several said 1:10,000 would be good enough odds to justify torture. If you survive, you can do things the dead never can. My hunch in this informal experiment is that the laypeople were the ones being rational, and the healthcare workers had been swayed by the distress they experienced as clinicians caring for sick patients.

This is crucial because a standard assumption in discussions about assisted suicide is that physicians are neutral observers, when in fact they are often highly influential voices in the process. And, critically, healthcare workers bring to the encounter with the dying their own irrelevant perspectives, their fatigue and frustration.

And here we get to the crux of the philosophical argument. When we’re talking about assisted suicide, what is functionally a request for state sponsorship of suicide, we’re not talking about an individual. We’re talking about a community. I don’t mean this in the sense of a community outweighing the voice of an individual. That isn’t necessary, and it isn’t true to the dynamic balance of Restoration theology. Instead, what I mean is that the people having to decide in this circumstance are the community. Whether to commit suicide or not may be a personal choice for the dying individual. Whether to sanction, facilitate, and approve the suicide is a choice for a community. What shall we, the community, do?

I need to pause here for a moment. One story that’s told about assisted suicide is of kindness and dignity, of autonomy and self-determination. The more I’ve stared at this problem, the more I’m convinced that this framing is wrong. To my eye, the question at hand is whether to rescue.

Rescue is a familiar problem. There is someone in need, and we can help. For the dying, rescue has an extra nuance. As they inspect the balance of their life, which will be both shorter and harder than they want it to be, the dying wonder whether their life is worth it. I am not asking what the dying should do. I’m asking what we who are not currently dying should do. We have options here, as a community, at least two ways to address their misery. Broadly speaking, do we rescue them, or do we put them out of our misery?

We have plenty of examples that come readily to hand. The Willie and Martin handcart company were marooned in Wyoming in the dead of winter in 1856. The Saints rushed from their established lives in Salt Lake City to rescue them; they did not ship them barbiturates to speed their deaths. The handcart story may feel tired by now, although it oughtn’t. But take another example closer to us in time. We rightly rush to the rescue of LGBTQ+ adolescents whose lives feel too heavy to bear. We rush to the rescue of shy or unusual children who are bullied. We rescue them from the belief that their lives are not worth living; we rescue them from suicide and self-harm. We make whatever sacrifices we must to ensure that they know their lives matter. And we should. We do not offer them a suicide pill. God forbid! There are many others whom society has terribly discomfited: prisoners, inner-city adolescents, the homeless, or political dissidents, for example. We know intuitively that it would be horribly wrong to offer them state-sanctioned suicide instead of rescuing them when their lives are unbearable.

I’m aware that rescue is hard work and that we have not built a society that easily remembers to rescue people with life-limiting illness. But we need to ask ourselves why we exclude certain vulnerable people from rescue. I’m also aware that shifting the focus of agency from the dying person to the community will impose a severe burden on us as a community. But that’s where the responsibility belongs: we shouldn’t be forcing vulnerable people to prove to us that they are worth our energies. We should be focusing on our own change of heart. No one in our presence should believe that they are better off dead.

As my fiercely independent Kate became weaker, more tired, less able to operate at her typically high level of strength, I was called to serve her. It was an intimate service—bathing, toileting, soothing, rubbing lotion, feeding. I noticed how sad this tenderness felt. And I wanted to understand why such intense dependency was a delight at the beginning of life and a sadness at its end.

This wondering drew me, strangely, toward Epicurean philosophy. The Epicureans had many complex beliefs that are poorly captured by the modern idea we associate with them, that we should “eat, drink and be merry.” One key Epicurean belief was that there is no pre-earth life and no post-mortal life, so wise men should not fear death. In defending the Epicurean mandate not to fear death, Lucretius—probably the most famous Epicurean after Epicurus—made a now classic argument. Basically, for Lucretius, if you don’t exist, you can’t possibly care about the fact that you are dead, so why worry about a future state in which you won’t have any feelings at all? His innovation came in declaring the time before birth equivalent to the time after death. Does the time before birth cause us grief? Not for anyone he knew. Since non-existence before birth is identical in terms of perception and experience to non-existence after death, if we don’t fear the time before birth, then we shouldn’t fear death. It's an elegant argument if you accept the premises. Of course, Latter-day Saints don’t accept any of this: there is robust, conscious flourishing in both of those temporal expanses: We are full-fledged spirit beings before and more advanced spirit beings after. But we don’t need to agree with Lucretius substantially in order to see him as calling out a non-rational distinction in our minds between getting started in life and wrapping up a life. We celebrate babies and walk hesitantly around the dying. We cheer at birth and weep at death. And maybe that’s not how we should be behaving.

Perhaps, in other words, there is something we can learn from the experience of loving those who are just getting started that can help us in loving those who are wrapping up. This concept became both painfully and beautifully clear to me as I cared for Kate in her last weeks. I remembered the first years of parenthood together. I relived all the new things the kids’ bodies and minds could do, the adventures, the wonder, the exhaustion, the unexpected changes in schedules, the need for extra strength and attention. And, of course, I inhabited the reality that each month, each week, each day, the child of a given moment dies, and a new child is born. It’s that bittersweet reality that you love the child so much that you want them frozen in amber, but you know that to be frozen is itself a form of death.

If we bring to the experience our heart and soul, loving someone at the other interface of non-mortal existence can honestly and truly and fully be like welcoming them into life. We can respond with wonder, even awe, at physiology, consciousness, and the grace of ensoulment as we move from sliver of amber to sliver of amber, in the always-ending, always-growing drama that is mortality. But this will take work, and it will take cultural re-orientation. Where the alternative is to kill vulnerable people who are responding to the many stigmatizing and marginalizing messages we generate, I don’t see another option.

This is hard work. I don’t doubt that even for a moment. I’ve lived it myself and know its difficulty with my whole body. But that hard work is, precisely, the meaning of life. Recall that Latter-day Saints believe that the purpose of mortality is to learn how to live heaven life. And heaven life is the life of the gods. And the gods love people who are struggling and suffering, and the gods never give up on them. Let’s stare at that for a moment: serving people who struggle is the work of eternity. If that is true, and it clearly is, what should we be doing with our mortal lives?

This grappling with Lucretius turned upside down has made clear to me just how distorted the marketing euphemisms for assisted suicide have become. We need to break free of the thrall of those words to see clearly. I’m speaking here of the notion that assisted suicide is “death with dignity” and Kate’s death was thus undignified because we supported her through the disability that marked the natural end of her life.

One common and in my view correct definition distinguishes dignity from respect. Dignity is unearned and inherent. It’s a basic human attribute. We all have inherent worth by token of being humans. It’s one of the defining features of modern liberalism, a tenet it inherits with minor modification from Christianity (as we noted above, the pagan world had no patience for the idea that a lower-class person had the same dignity as an upper-class person). By this definition of dignity, whatever you choose to do to a person, however they suffer or stumble, whether you choose to kill or not kill a person or assist them in suicide or not, you do not affect their dignity. You can, however, choose to respect that dignity. Respect refers to actions and mindsets that appropriately honor the inherent dignity of another person. Respect, not dignity, should be our focus.

If we hold instead that dignity is a feature of able-bodied folk without cognitive impairment, we’re right back in the brutal world of classical paganism. In that world, people with disabilities lacked dignity. A death associated with disability was undignified. Better to dispense with the vulnerable person than to witness their mounting weakness, the thinking goes.

To reiterate in hopes of clarity: we do not create dignity with our actions, we respond to it. If we respond to that dignity well, then we are being respectful, but we have in no way changed the dignity of the other. All humans die with dignity.

The question, then, is whether we respect the dying. Do we learn from them, do we serve them, do we attend to their needs, do we leave them comfortable with their imposition on us? The concept underlying human dignity is that we are all as worthy as the Queen of England. If the Queen needs help going to the bathroom, a dozen assistants jump to the work. If she needs help being fed, if she needs her pillow fluffed, if she needs help walking, teams are ready to serve her, instantly and enthusiastically. Why would we do any less for those who are confronting the end of their lives?

Our experience with Kate, buoyed by our inversion of Lucretius’s argument, was that we respected her dignity. We found ways to serve her. The community—and it wasn’t just us, not by a long shot—rallied together as the Saints do. We carried our Kate as on a litter. We served her as thoroughly as staff would serve the Queen of England. We were able to communicate to her the opposite of a suicide pill—we welcomed her in her weakness, we respected her dignity even when our Darwinian natural beings wanted to look away. We were able to do hard things.

And there the narrative and the philosophical arguments come together. The question of assisted suicide is a litmus test for those of us who are not yet actively dying. Will we rise to the occasion, or will we tell ourselves stories about how this particular type of vulnerable person is better off dead? Will we add our voices and our bodies to the work of rescue, or will we hope that a state-sponsored suicide pill will make life easier for us? Will we lean into the work of hospice, which by all credible accounts addresses the overwhelming majority of physical symptoms, or will we hope for shortcuts? What kind of society do we intend to build, and how comfortable are we letting go of partisan attachments to join the currents of Restoration doctrine? I’m eager to see what comes next.

Samuel Brown is a physician scientist who also wonders about bigger questions. He’s parenting three children at the cusp of adulthood and writes books from time to time.

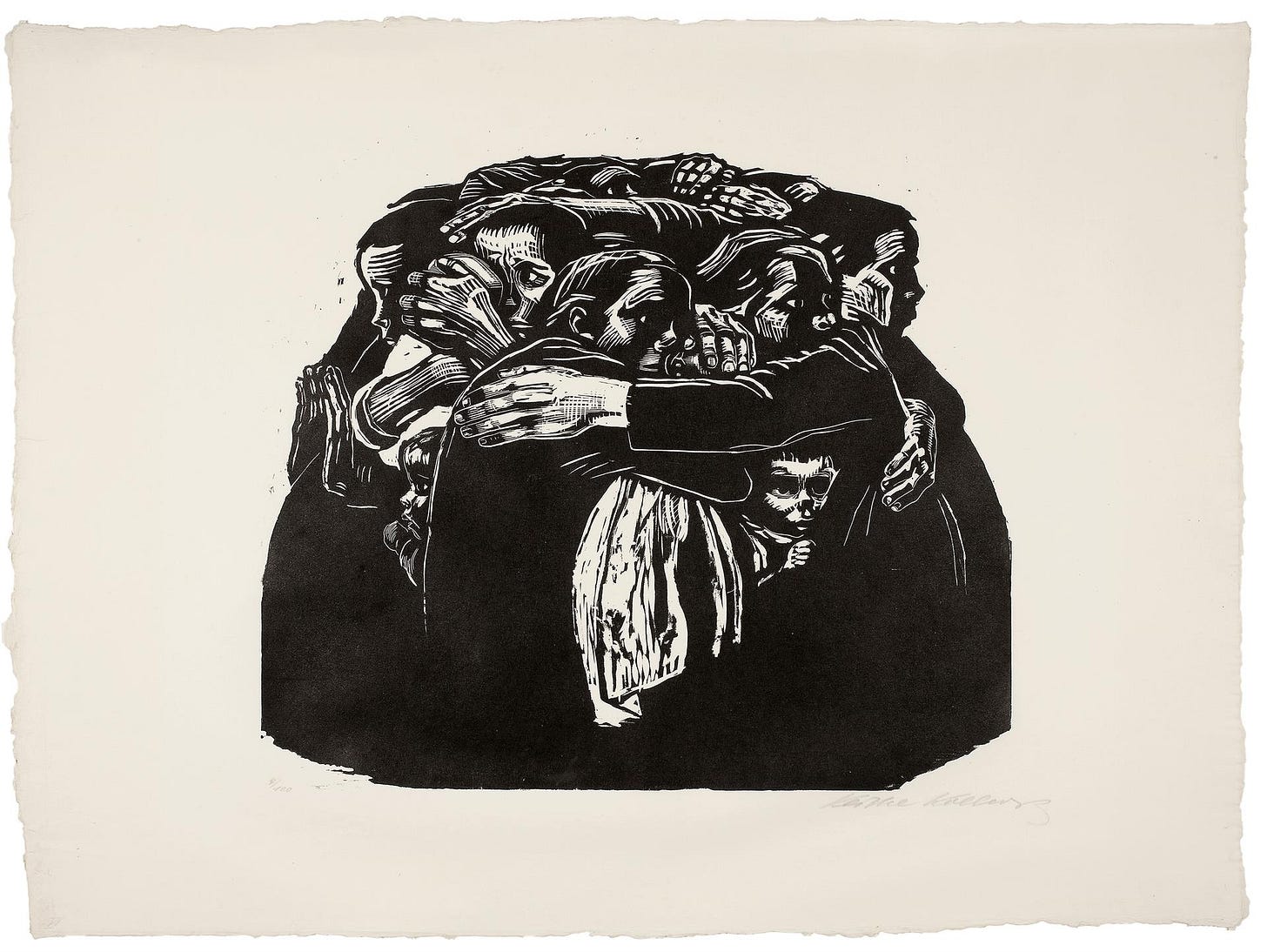

Art by Käthe Kollwitz.

Thank you, Brother Samuel, for living, and thinking, and sharing these truths. Your knowledge and insight is a vicarious gift to those of us who have suffered differently and it points, gratefully, to the vicarious suffering of our Lord. Peace be upon you and upon your beloved, Kate, of blessed memory.